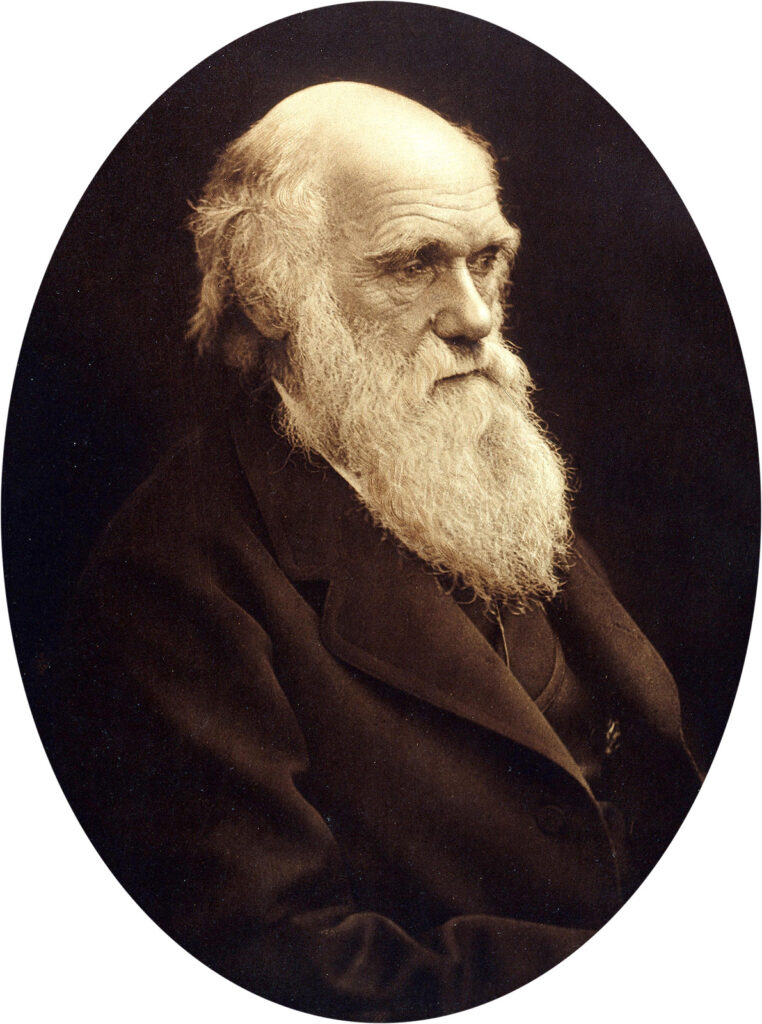

Did you know Charles Darwin suffered from lupus? Narcolepsy, too. Plus middle-ear damage, pigeon allergies, agoraphobia, chronic fatigue syndrome, an adrenal-gland tumor, Chagas disease, and something called smoldering hepatitis.

At least that’s what modern-day medical sleuths would have you believe. These sleuths—mostly doctors and medical historians—have published scores of papers retroactively diagnosing Darwin with every one of those ailments, all to solve the mystery of why the father of modern biology was so sickly during his lifetime.

To be sure, Darwin endured chronic poor health. His long list of symptoms included boils, fainting fits, heart flutters, numb fingers, insomnia, migraines, dizziness, eczema, and horrendous gas. But above all, Darwin vomited. He vomited after breakfast, after lunch, after teatime—whenever—and kept going until he was dry heaving. In peak form he vomited 20 times an hour, and once vomited 27 days running.

Poor health upended Darwin’s whole existence, often preventing him from visiting people’s homes or attending scientific meetings. He never wrote for more than 20 minutes without pain somewhere, and he cumulatively missed years of work with various ailments. He even grew out his famous beard partly to soothe the itchy eczema that plagued his face.

Charles Darwin.

Something, then, was clearly wrong with Darwin. But nailing down exactly what has proved a mug’s game, as that list of potential diagnoses shows. Indeed, the list is almost comical in its range, veering from autoimmune diseases, to viral infections, to cancer, to mental disorders.

Part of the problem for those trying to retrodiagnose Darwin is that it’s not clear which of his symptoms are important and which are red herrings, or whether he suffered multiple afflictions at once. The truth is, no one really knows what ailed Charles Darwin, and unless new historical evidence comes to light, we likely never will.

Darwin is hardly alone in being put under a medical microscope—there’s a veritable cottage industry of people pinning diseases and disorders on historical celebrities. Frédéric Chopin has been posthumously diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, Fyodor Dostoyevsky with epilepsy, Edgar Allan Poe with rabies, Jane Austen with adult chicken pox, Vlad the Impaler with porphyria, and Alexander the Great with West Nile virus. Nor have scholars shied away from psychological disorders. Vincent van Gogh has seemingly been diagnosed with half the DSM.

As a variation on this game, psychologists sometimes diagnose prominent figures from afar in their own lifetimes, especially politicians. Their track record is no less spotty.

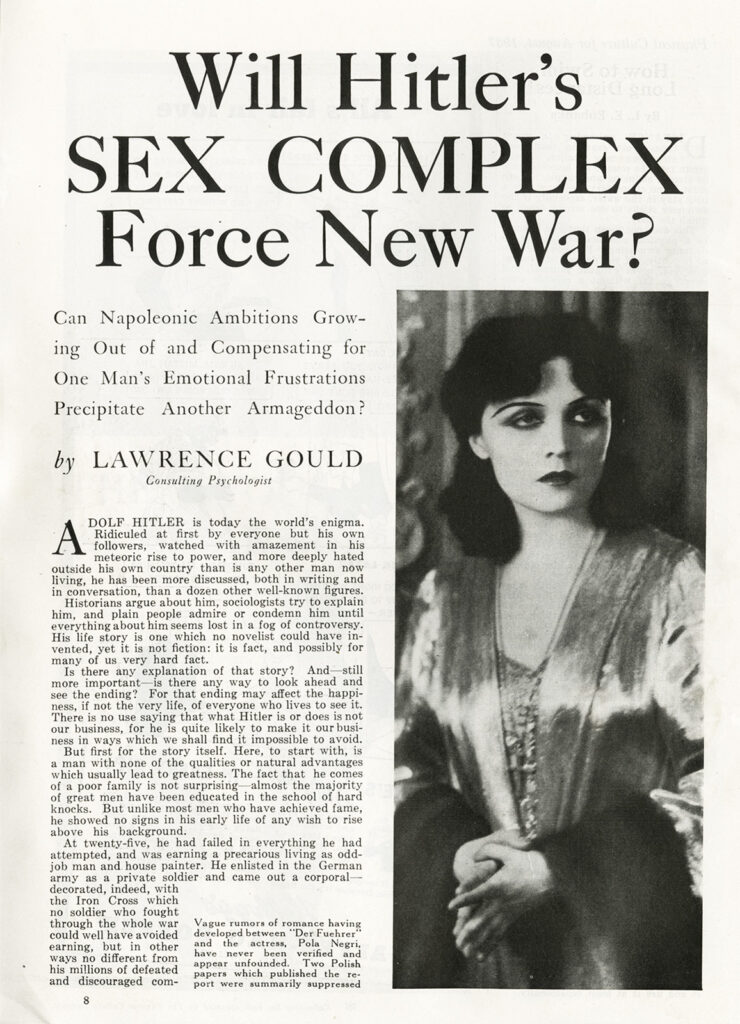

Article from the August 1937 issue of Physical Culture.

The most egregious examples involve Adolf Hitler. During World War II, the Office of Strategic Services—the chaotic, freewheeling predecessor of the CIA—commissioned multiple reports on Hitler’s mental state, long passages of which read like a parody of Freudian psychobabble. One analyst noticed in Hitler’s family “a strong libidinal attachment between mother and son,” and speculated that Hitler no doubt feared his father would castrate him. The analyst added that Hitler “must have discovered his parents during intercourse [once],” despite there being zero evidence for this ever happening.

More troublingly, the analyst concluded, again without evidence, that Hitler “derives sexual gratification from the act of having a woman urinate or defecate on him.” The analyst then claimed that Hitler’s hatred for Jews was a direct result of his shame over this fetish—that Hitler hated how unclean his desires made him feel and then projected that self-loathing onto the Jewish people. In addition to being ridiculous logic, conclusions like this ignore the political, social, and historical context that fueled Hitler’s rise. In this analyst’s mind, one pervert comes to power, and the Final Solution is the inevitable result.

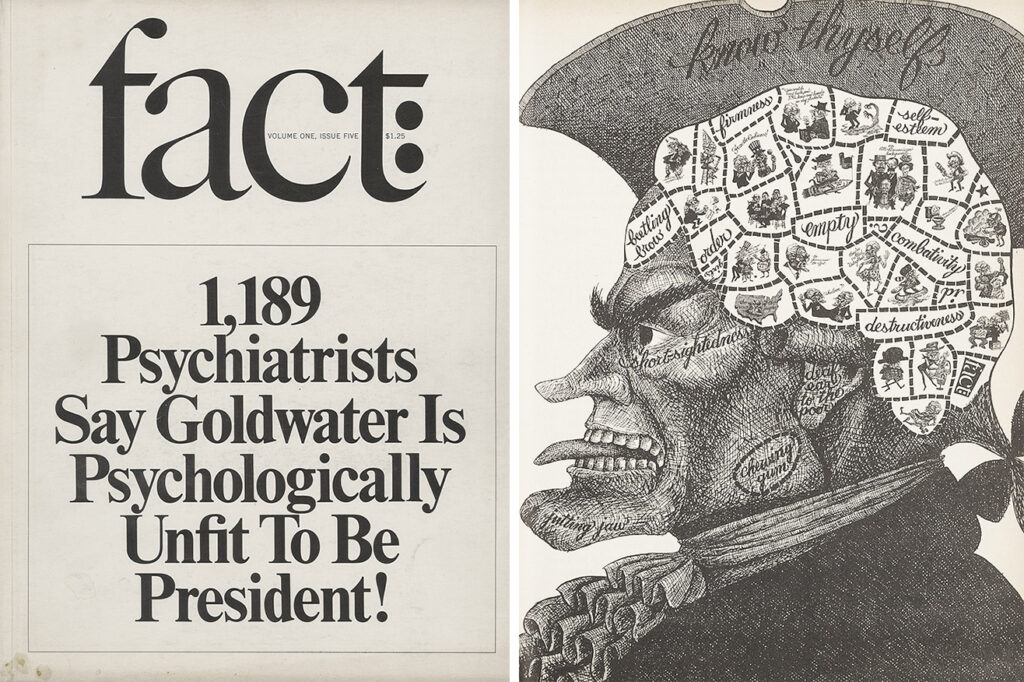

Despite such howlers, psychologists continued to scrutinize political leaders from afar over the next few decades. In 1964, Fact magazine polled the nation’s psychiatrists and published a story claiming that nearly 1,200 found Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater “unfit” for the White House. Goldwater later sued the magazine for libel and won, and the fiasco led the American Psychological Association to institute the so-called Goldwater rule, which ethically bars psychologists from diagnosing prominent figures whom they have not personally examined. Not that the rule has stopped the practice. As American politics has gotten more heated and divisive over the past few decades, many mental health professionals have violated the rule and weighed in on the mental fitness of Donald Trump, Joe Biden, and others.

Left, The cover of the September–October 1964 issue of Fact. Right, A caricature of Barry Goldwater from the issue adopted motifs from phrenology charts.

Some psychologists argue that the need to avert what they see as unprecedented potential crises should override the Goldwater rule. Defenders, meanwhile, have pointed out the dangers of abandoning it. Weighing in on such matters makes mental health professionals look like partisan hacks, which undermines their credibility. Worse, calling for the removal of political figures from office inadvertently promotes the stereotype that mental disorders are terrible, shameful afflictions and that people with mental disorders cannot possibly do their jobs.

The dangers of diagnosing people with mental disorders from afar is all the more acute because what’s deemed a mental disorder is often highly dependent on cultural context and can shift from one era to the next. As a stark example of this, one Soviet psychiatrist during the 1980s believed premier Mikhail Gorbachev was obviously mentally ill, suffering from “sluggish schizophrenia”—a disease whose symptoms included a “struggle for the truth, perseverance, reformist ideas, and willingness to go against the grain.” Only after the Soviet Union collapsed did the psychologist realize that she was the one with a skewed perspective.

If psychologists diagnose politicians from afar to avert potential crises, the motivations for posthumously diagnosing Darwin and other historical figures aren’t so clear. The impulse probably stems in part from our obsession with celebrities—it’s respectable gossip. It’s also partly a pedantic desire to know every last thing about a famous person’s life. A more important question, however, is what insight the diagnosticians are hoping to gain. If we could prove that some artist or king really did have such-and-such an ailment, how much would we really learn?

Sometimes—especially by deploying genetic analysis and modern scanning tools—scientists can indeed learn important things or settle long-standing disputes. Take the case of Akhenaten, an Egyptian pharaoh from the 1300s BCE. Although best known today as the father of King Tut and husband of Queen Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s life has fascinated Egyptologists for centuries. Amid fierce opposition, Akhenaten remade Egypt in several ways, instituting radical new religious and artistic practices into an ultraconservative society. Some scholars have called him history’s first monotheist for his elevation of the Egyptian sun god above all other deities.

A colossus of Amenhotep IV, before he changed his name to Akhenaten, originally from the Karnak Temple Complex in present day Luxor, Egypt, ca. 1353–1347 BCE.

With regard to the art from Akhenaten’s reign, though, something has always seemed strange. That’s especially true with depictions of Akhenaten and his family. In statues and carved reliefs, the features of Akhenaten’s face and body often appear exaggerated, even deformed. Archaeologists describing these portrayals sometimes sound like crude carnival barkers. One promises you’ll “recoil from this epitome of physical repulsiveness.” Another calls him a “humanoid praying mantis.”

These archaeologists were no doubt being provocative, but many scholars have noted unusual traits in portraits of Akhenaten, including an almond-shaped head, spidery arms, legs with backwards-bending knees, Botoxed lips, a concave chest, a pendulous potbelly, and more. This is all the more puzzling because other elements of Egyptian art during Akhenaten’s reign—such as flowers, animals, and everyday people—are depicted in highly realistic ways. So why did Akhenaten’s family look so different?

Archaeologists trying to understand this puzzle fell into one of two camps. Some maintained that the portraits of Akhenaten were stylized and not meant to be realistic. Meanwhile other archaeologists proposed a more daring idea: the portraits were realistic, and Akhenaten had a rare medical disorder, such as Fröhlich syndrome or familial gynecomastia, that produced an unusual body shape. And frankly, familial gynecomastia or another genetic disorder isn’t a bad guess, given all the incest in pharaonic lines. (Incestuous relationships produce offspring with far higher rates of birth defects.) But however suggestive, these diagnoses suffered from a complete lack of evidence.

The medical-disorder idea was put to the test in 2007, when the Egyptian government allowed scientists to withdraw DNA from five generations of royal mummies, including Akhenaten. When combined with CT scans of the corpses, this genetic work helped scientists investigate what disorders, if any, Akhenaten might have suffered from.

Overall, the study turned up no major defects in Akhenaten or his family, which implies that the Egyptian royals looked like normal people. That in turn supports the idea that portraits of Akhenaten and his family—which sure don’t look normal—probably weren’t striving for verisimilitude. Most scholars now believe they were likely propaganda: Akhenaten may have decided his status as pharaoh lifted him so far above the normal human rabble that he had to inhabit a new type of body in public portraiture. Some of Akhenaten’s features (e.g., a distended belly) call to mind fertility deities as well, so perhaps he wanted to portray himself as the womb of Egypt’s well-being. Overall, then, investigating the medical status of Akhenaten has greatly informed the debates about his era’s political and artistic practices.

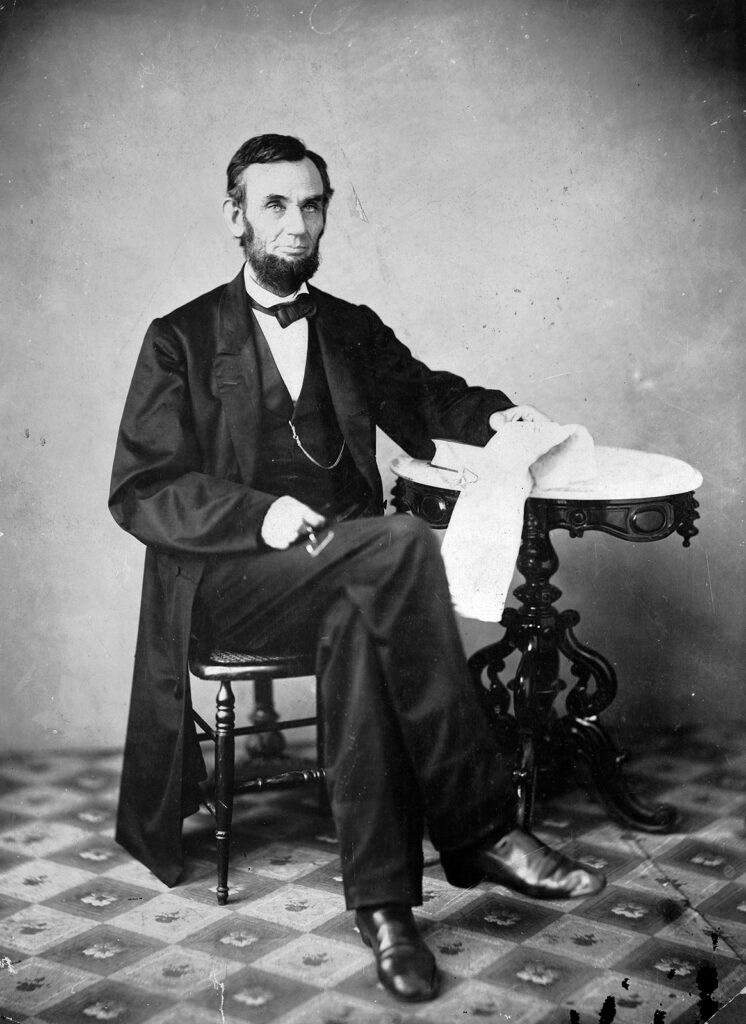

Abraham Lincoln, August 1863. Lincoln’s physical features have led many doctors and historians to speculate about his medical status.

In other cases, however, the value of retrodiagnoses is far less clear. Multiple doctors and historians have speculated that Abraham Lincoln had Marfan syndrome, partly because Lincoln’s gaunt physique and spidery limbs look classically Marfan. But let’s say geneticists extracted some Lincoln DNA and tested it. (There’s plenty available in the bloody artifacts that were saved from the night Lincoln was shot.) And let’s say they proved he had the disorder. Would knowing this really illuminate Lincoln the man? Would we really understand anything more about him, or his era, or the decisions he made if we could diagnosis him more than 150 years after his death?

And at least in Lincoln’s case, the would-be sleuths have a clear hypothesis to refute or prove. Most cases of attempted diagnosis resemble Darwin’s, where there’s a constellation of symptoms of unclear importance. Even worse, especially in classical times, the symptoms were sometimes recorded decades or even centuries after the person died, making them as much legend as fact. There’s no guarantee the symptoms were recorded accurately, either, especially in the absence of a doctor.

There are also ethical concerns about scrutinizing people’s medical histories. Some retrodiagnosers have argued that historians already scour people’s private diaries and letters, and that examining medical records or taking genetic samples simply extends this license a little further. But the analogy doesn’t quite hold, especially with genetics, because DNA can reveal things that even the person in question didn’t know. Perhaps that’s not so terrible if they’re safely dead, but living descendants might not appreciate their family health history being outed.

Pointing out the flaws in retrodiagnoses will almost certainly not curb the practice. New papers appear all the time, and some brave souls even extrapolate from the diagnoses themselves to make sweeping counterfactual claims about how such-and-such an illness might explain the genesis of a war or artistic masterpiece. For the most part, there’s little harm done in speculating about a historical celebrity’s health, so a Goldwater rule for retrodiagnosing probably isn’t in order. But a little humility might be. The mystery of what ailed Darwin and so many others is one we’ll likely have to live with.