Perhaps no painter in history ever used color more precisely than Claude Monet. To create his famous pond and water lily paintings, he would obsessively return to the same scene dozens of times to capture every detail of shade and hue, and the results impressed even other legendary painters. As Paul Cézanne once said, “Monet is only an eye—but my god, what an eye.”

In the 1910s, however, Monet’s vaunted eyes came under threat. He developed cataracts and, painfully, slowly, began going blind. He admitted to friends that he would likely have to quit painting soon, and the thought crushed him: for Monet, life without painting was no life at all.

There was one hope, however—surgery to remove the cataracts. Unfortunately, this procedure was not the routine operation of today; it carried great risk. Monet had in fact seen his friend and fellow artist Mary Cassatt effectively go blind after two failed cataract surgeries; she never picked up a brush again.

Eventually, though, with his artistic life at stake, Monet screwed up the courage to go under the knife. And remarkably, the surgery introduced a whole new phase in his career, because it seemingly changed how his vision worked. Already a master of color, he may have gained the ability to see color beyond the normal human spectrum—and peer into the realm of the ultraviolet.

Humans have special cells in our eyes called cones that detect color. We have three types of cones, but most mammals have just two and have relatively limited vision palettes as a result. For example, stop signs look blaringly red to us. But dogs can’t see red because they lack the right cone. Red just looks blah to them, grey and muted.

In contrast, some animals see a wider range of color than we do. The human vision spectrum starts at red (around 750 nanometers) and extends to violet (380 nanometers). But beyond normal violet light, there’s ultraviolet, or UV light, which has shorter wavelengths.

To us, ultraviolet light is invisible. But many animals can see UV light, especially insects. Some even depend on this sight to survive. Certain butterflies use ultraviolet spots on their wings to distinguish males from females. Similarly, certain species of flowers that look plain to us actually have all sorts of ultraviolet stripes and swirls to attract bees. (Some scientists even call this ultraviolet hue “bee purple.”) Overall, there’s a whole world of color out there right under our noses that’s completely invisible.

At least to most of us. Monet’s road to seeing ultraviolet light began in 1905, the year he turned 65, when he noticed that his 20/20 eyesight was getting fuzzy. By 1912 his vision had dropped to an estimated 20/50 and kept sinking.

Even worse, his prized sense of color started to dull. Colors just didn’t pop for him like they used to. Everything looked a bit browner, a bit muddier, each year. Monet finally consulted an eye doctor, who diagnosed cataracts.

Cataracts arise when proteins build up on the lens of the eye, proteins that turn the lens yellow and block or scatter light. People can develop cataracts for multiple reasons, including old age, but with Monet, some historians speculate that the lead-based paints he used might have contributed.

Regardless, Monet had a very human reaction to his diagnosis. He ignored it, hoping it would just go away. Meanwhile, he kept painting as much as possible, trying to adjust to his new reality. Because cataracts can cause glare, he had to wear floppy straw hats outdoors now. And he could paint only near dawn and dusk, when the light was gentlest.

Predictably, ignoring the problem fixed nothing, and his eyesight continued to deteriorate. Between 1912 and 1918 his vision dropped from roughly 20/50 to 20/100. By 1922 he was down to an estimated 20/200, legally blind.

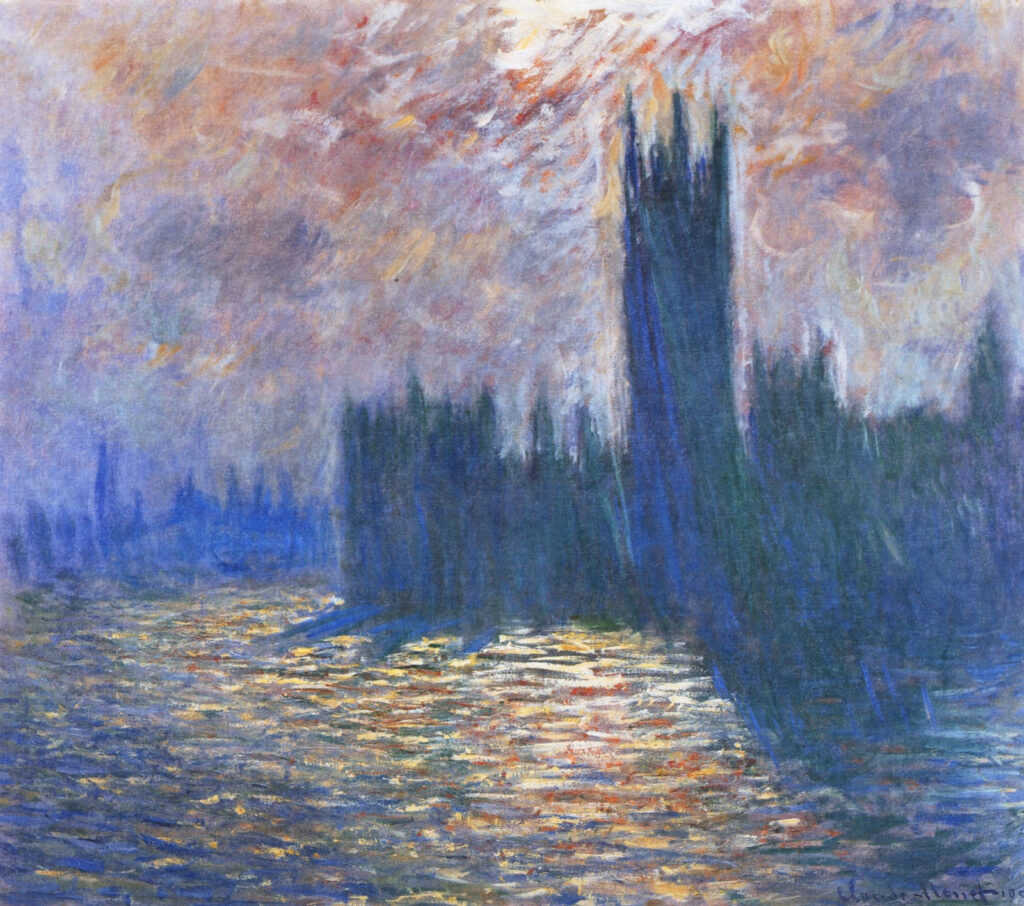

Monet’s painting was deteriorating, too. Instead of the fine, intricate strokes he used before, his brushstrokes now became coarse and thick. There was no more light touch, no more airiness. His color schemes changed as well. He especially had trouble seeing “cool” colors, such as blue and green: water lilies looked brownish now, and ponds looked like stagnant swamps.

As things got worse, Monet tried to make up for the muted greens and blues by dialing other colors up—fiery reds and yellows. In some cases, his beloved gardens resembled an inferno. It’s like Monet’s own private vision of hell.

As he grew more desperate, Monet began visiting doctors as far afield as London, begging for treatment. Each one told him he needed cataract surgery. He always refused. After the surgery ended Mary Cassatt’s career in 1919, Monet’s resolve only hardened.

But things got so bad that, by 1922, Monet could barely tell certain hues apart. He had to label his paint tubes with big block letters, and then put the paint in the same spot on his palette every day simply to find it.

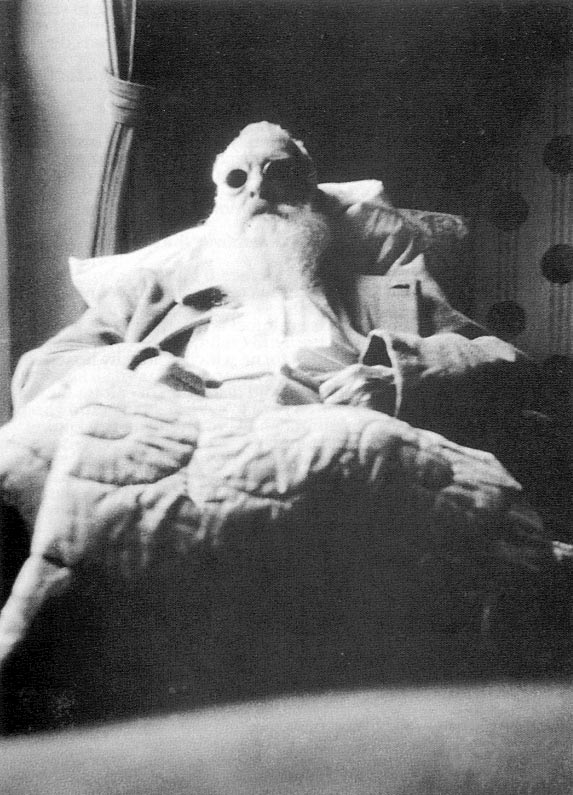

Eventually, Monet had no choice but to face the dreaded surgery. It took place in January 1923. The doctors operated on one eye only (most sources say the right), so in case something went wrong, he’d have a backup eye. During recovery, he had to lie absolutely still for days, his head jammed between heavy sandbags to make sure he couldn’t move. Then for weeks afterward he had to wear bandages around his eye, which itched like crazy. He clawed at them like a dog.

Scarily, the initial results were every bit as bad as Monet feared. When the bandages were removed, he had to wear special glasses that distorted everything like a funhouse mirror. He called this recovery phase a “terrifying” ordeal and began lashing out at everyone around him. He was convinced that, like Cassatt, his career was over.

Ultimately, however, Monet escaped Cassatt’s fate. His eye healed, and in 1924 he finally got a new pair of glasses specially crafted for postoperative cataract patients. The glasses were expensive: a single pair cost as much as a four-room luxury apartment. But lucky for him, they worked. His terrifying funhouse world finally started to look normal.

Or, at least, mostly normal. As noted, human beings do not see ultraviolet light. But this shortcoming arises not for the same reason that, say, dogs cannot see red. Dogs can’t see red because their cones can’t detect it. In contrast, human cones can perceive UV light if given the chance. It’s faint, but it’s there.

What prevents us from seeing UV light is our lenses, which filter it out. But when Monet’s lens was removed, that constraint was lifted. His work from this period suggests he may have been able to perceive that mysterious bee purple. To insects, water lilies would have a violet aura, and sure enough, Monet started rendering the flowers with overtones of blue and purple.

(Presumably, the always-precise Monet would have painted the water lilies with ultraviolet-colored pigment if that had been available. Because it wasn’t, those of us with intact lenses can see hints of what Monet was getting at.)

Monet isn’t alone here, either. Eye surgeons still remove the lenses of cataract patients today, and usually replace them with artificial lenses that block UV light. But prior to the 1980s the lenses did not block out UV rays, and not everyone gets the lenses anyway. As a result, such people can often perceive that secret world of spotted butterflies and swirly flowers. More prosaically, people at pubs suddenly notice the ultraviolet black lights that bartenders use to weed out counterfeit bills. To most people black lights are more or less invisible. To people without lenses, they’re glaring.

After his surgery, Monet renounced the paintings he’d made during his cataracts phase. His sight restored, he now hated the coarse brushstrokes and garish colors. There are even stories, perhaps apocryphal, of him smuggling paint into galleries and “correcting” his pieces on the wall when no one was looking.

Other pictures, though, did not seem salvageable. As he once said, “I would be seized by a frantic rage” on seeing them, and he slashed several with penknives.

But some scholars today view these cataract paintings as valuable in their own way. They’re the product of diseased eyes, no question. But knowing how people with cataracts view the world is important data for vision scientists and eye doctors.

The pictures are artistically important as well. By the 1920s the painting world had largely shifted from impressionism to less representational art. In these new art movements, painters often used colors in novel ways to distort images. Colors didn’t need to conform to reality, either. You could make the ocean red or the sky green, or whatever else captured your emotional state.

However inadvertently, Monet had done something similar with his garish colors and thick brushstrokes. So although Monet despised the cataract paintings, some scholars see them as a bridge between 19th-century impressionists and 20th-century abstract expressionists. It might have been an accident, but history has swerved before on less than that.