Worldwide nearly 3 million workers die on the job each year. U.S. workers experience roughly that same number of injuries and illnesses each year. Work is hard and dangerous, and we have the data to prove it. But who started collecting that data? The answer takes us back to Paracelsus, an early modern physician, and alchemist who noticed that the miners he lived among often became very ill or died. His inquiries laid the foundation for occupational health and the workplace safety standards we have today.

Credits

Hosts: Alexis Pedrick and Elisabeth Berry Drago

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: James Morrison

Music by Blue Dot Sessions: “Dirty Wallpaper,” “Caprese,” “Pat Dog,” “Crosswire,” “Tiny Putty,” “Rose Ornamental,” “Donnalee,” and “Nesting.”

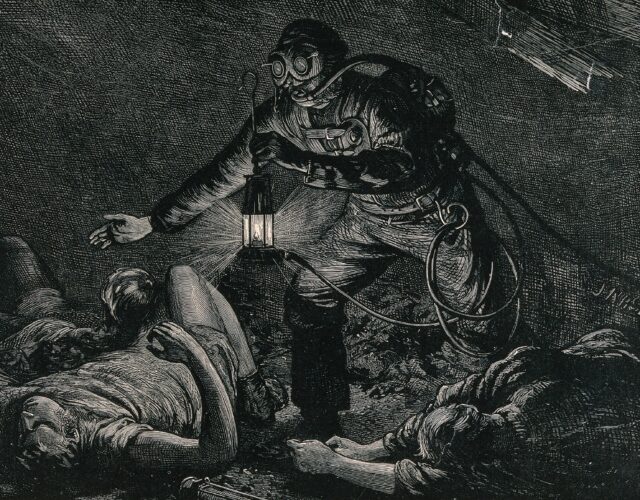

Image courtesy of Wellcome Collection

Resource List

“Alice Hamilton and the Development of Occupational Medicine.” American Chemical Society.

“Alice Hamilton.” Science History Institute.

Ball, Philip. The Devil’s Doctor: Paracelsus and the World of Renaissance Magic and Science. London: Arrow, 2007.

Blading, Michael; Heather White. “How China Is Screwing Over Its Poisoned Factory Workers.” Wired, April 6, 2015.

Breathnach, Caoimhghin.“Bernardino Ramazzini and His Treatise of the Diseases of Tradesmen.” Irish Journal of Medical Science 169 (2010), 68–71.

Bressan, David. “Physician Paracelsus and Early Medical Geology.” Scientific American, September 26, 2014.

Franco, Giuliano. “De morbis artificum diatriba [Diseases of Workers].” Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1940.

Kelly, Emily. “Paracelsus the Innovator: A Challenge to Galenism from On the Miner’s Sickeness and Other Miners’ Diseases.” University of Western Ontario Medical Journal 78 (2008), 70–74.

Moran, Bruce. Paracelsus: An Alchemical Life. London: Reaktion, 2019.

Nagy, Kimberly. “The Woman Who Founded Industrial Medicine.” Scientific American, October 23, 2019.

“Occupational Medicine.” American Medical Association.

Ramazzini, Bernardino. “De morbis artificum diatriba [Diseases of Workers].” American Journal of Public Health 9 (2001), 1380–1382.

Transcript

Archival: In 1968, at the height of the war in Vietnam, 14,000 Americans were killed. And 46,000 were wounded. That same year, another 14,000 Americans were killed, but those lives were lost right here in the United States. Because those American men and women were killed at work. On the job. Another two and one half million American workers suffered disabling injuries.

Alexis Pedrick: Throughout the world, nearly three million workers die on the job each year. And the U.S. sees roughly that same number of worker injuries each year. Work is hard and dangerous. And we have the data to prove it.

Lisa Berry Drago: But have you asked yourself why do we have that data? How does the United States Bureau of Labor, and more specifically the Occupational Safety and Healthy Administration, or OSHA, keep tabs on worker health? Who sets the standards and regulations they enforce? How do we know what occupations are the deadliest? Or even what specific risks workers should be protected from?

Alexis Pedrick: If you’re wondering what the top five most dangerous professions are, in 2019 they were logging, fishing, flying planes, roofing, and sanitation work.

Lisa Berry Drago: Rounding out the top 10 most dangerous jobs are truck and delivery drivers, agricultural workers, iron and steel workers, construction workers, and landscapers. If you’ve ever worked any of these jobs, that list definitely won’t surprise you.

Alexis Pedrick: Early public health pioneers called these the dangerous trades. Technically speaking, people have been getting hurt on the job and being treated by doctors for those hurts since jobs and doctors were invented. But occupational medicine didn’t exist as a distinct field of study in the United States until after 1900. And only a little earlier than that in Europe.

Lisa Berry Drago: Not to mention, even after occupational medicine was established, it took decades for lawmakers and industry to catch up. The US Department of Labor wasn’t formed until 1913. And OSHA didn’t exist until 1971.

Alexis Pedrick: When we started digging deeper into the history of occupational medicine, we realized some even stranger facts.

Lisa Berry Drago: The first is that one of the most important occupational medicine researchers ever, Alice Hamilton, was Harvard’s first woman faculty member. But despite her incredible accomplishments, she was never promoted or recognized.

Alexis Pedrick: The second was that Hamilton was not the first person to try and catalog the most dangerous trades. That honor may actually belong to a 17th century Italian professor, Bernadino Ramazzini.

Lisa Berry Drago: And the third was that even Ramazzini wasn’t anywhere near the first person to actually create an occupational health case study. That honor belongs to an alchemist.

Alexis Pedrick: We told you it was going to get strange. I’m Alexis Pedrick.

Lisa Berry Drago: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago, and this is Distillations. Chapter One: The Most Dangerous Trade.

Alexis Pedrick: The key truth about occupational medicine is that investigating the hazards of work means caring about workers. And for a lot of history, society just didn’t. Work needed to get done, and many of the people doing that work were viewed as disposable.

Lisa Berry Drago: Take mining for example. Historically one of the most dangerous professions. Minerals needed to be mined for chemical processing in industry. Gold and silver needed to be mined for currency. And if that meant some miners died in the process, well, that was unfortunate but it was just the cost of doing business. Workers were another kind of resource to be used or used up as needed.

Alexis Pedrick: When we say that mining was historically dangerous, we mean that literally. Even ancient Greeks and Romans commented in their writings about how many miners seemed to die every year. They remarked on it almost like it was a fact of nature. Sky’s blue, water’s wet, wow, miners sure do die a lot.

Lisa Berry Drago: It’s not that they didn’t form theories about why that was, or where illness came from. The second century Roman physician Galen proposed that human bodies contained four distinct humors, or bodily essences. Phlegm, blood, yellow bile, and black bile. If these humors were in balance, the body would stay healthy. If they were unbalanced for whatever reason, illness could follow.

Alexis Pedrick: In the Galenic view of health, sickness came from within the body. It was an internal imbalance. Solutions ranged from blood letting to release quote, unquote, “excess blood”, to purges and fasting designed to rebalance the humors.

Lisa Berry Drago: Galen and other ancient thinkers did recognize one other possible source of sickness. Miasmas, or bad air. They thought miasmas were created by waste or rotting things. And that once they were smelled or inhaled, they could spread sickness.

Alexis Pedrick: Miasmas were very different from the modern concept of airborne disease. Since germ theory was a thousand years away, it was the air itself that was considered suspect. The cure was simply to breathe in fresher air. But you’d have a hard time doing that down in a mine.

Lisa Berry Drago: Right around the 14th century, the demand for metal skyrocketed. New methods in agriculture and warfare called for more iron and more copper. While a newly global marketplace meant that more coin was circulating, meaning more gold, more silver, and more copper again. This meant a need to dig mines deeper and deeper. Hence the tunnel mine, long shafts stretching underground.

Alexis Pedrick: Tearing up all that rock and mineral, in both kinds of mines, sent all kinds of particulate matter into the air. And into miner’s lungs. To increase air circulation, some mines used giant bellows, essentially pressurized air sacks, to send fresher air down into the tunnels. This was, I mean, better than nothing.

Lisa Berry Drago: There was also the problem of flooding. Digging deep underground means passing through layers of groundwater. Mines used enormous wheel powered pumps to pump out water, but when those failed miners drowned. Even when they worked correctly, mines were cold and extremely damp places.

Alexis Pedrick: But wait! There’s more! Like major toxicity. A lot of what was getting dug up alongside the copper and gold were substances like arsenic, mercury, and lead. Miners could breathe them in as dust or absorb them through the skin through their clothing and hair.

Lisa Berry Drago: Delicious. When these miners came up out of the ground in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries, coughing and feverish, feeling sluggish, their joints weak, and their stomachs nauseous, basically showing all the signs of lung disease and heavy metals poisoning, what did they get? Galenic medicine. Blood-letting, purges, and so on.

Alexis Pedrick: One of the reasons we know so much about what these early modern miners suffered, was that at least one person did care about them. He cared enough to create one of the first true case studies of a hazardous occupation. He not only recorded their symptoms and the treatments they tried, he documented the conditions they worked in. And how they and their families lived. Because, well, he was living right alongside them.

Lisa Berry Drago: His name was Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim. Whew, if you can say it five times fast, you are probably him or his parents.

Alexis Pedrick: Thankfully, in many of his writings he’s simply called Paracelsus, meaning equal of Celsus.

Lisa Berry Drago: Celsus was another ancient physician, less well known than Galen, who was an early champion of firsthand observation. As we’re about to explain, that title was therefore pretty fitting.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Two: The First Occupational Health Case Study.

Lisa Berry Drago: Paracelsus was born in the Swiss village of Einsiedeln around 1494. His father was the illegitimate son of a local noble family who earned his living as a physician. His mother was a bond servant, a kind of indentured worker, in a local church hospital.

Alexis Pedrick: Their marriage crossed class lines. Children of a mixed class marriage automatically belonged to the lower of the two classes. This meant that Paracelsus never really escaped the legal limitations or the social stigma of being a bond servant’s son.

Lisa Berry Drago: But he also never forgot his roots. When his intellectual rivals attacked him for being lowborn, he would proudly admit to being quote, “cut from course cloth.” In fact, he often argued that his humble origins made him a better doctor.

Alexis Pedrick: In the case of miner’s disease, that seems to be true. His sympathy, or maybe empathy for miners and laborers, and his genuine desire to help them, it comes across in all his writings.

Lisa Berry Drago: As a teenager traveling with his father, he lived in a mining region near Villach in what’s now Austria. Later, due to his interest in studying alchemy and metallurgy, he lived for several years in mining towns in the Tyrolean Mountains. Like his father before him, Paracelsus lived alongside the miners and treated them and their families, listening to their complaints and worries. And his written identifications of symptoms were some of the most detailed clinical studies ever recorded to that point. He described the types of coughs they suffered, wet or dry, racking or choking, and their frequency. And the cycle of fevers and chills, the way certain conditions would advance and retreat.

Alexis Pedrick: He noticed that in mining towns, it wasn’t just the miners who got sick. Once the metal and mineral ores came out of the ground, they had to be processed. Workers called smelters heated up and separated ores by type while assayers evaluated and tested their quality. These workers also experienced similar symptoms. Muscle cramps and weakness, nausea and vomiting, brain fog. Paracelsus concluded that it was from breathing in heavy metal fumes.

Lisa Berry Drago: He also observed that all of these workers’ families could suffer from some of the same conditions, since they too encountered lots of metal dust. And because they drank water from local sources, which he concluded was probably tainted by the mining process.

Alexis Pedrick: All of this firsthand observation was in itself pretty important. Paracelsus was at the forefront of a new approach to medicine, and the science that we now call empiricism. Empirics believe that true knowledge was derived from the senses, from lived experience. This now sounds so basic. Of course we need observation for science. But that’s not what Galen thought.

Lisa Berry Drago: Paracelsus didn’t believe in Galen’s bodily humors. Instead he thought of the body as a laboratory, constantly transforming the materials it took in. If it took in good materials, it could turn them into good health. If it took in harmful materials, it could filter them out and turn them into waste, unless the body took in too many toxic substances and got overwhelmed.

Alexis Pedrick: He encouraged aspiring doctors to spend time with their patients, listening to them, examining all of their symptoms, not just reading a diagnosis from a book. He also believed in talking to other kinds of healers like midwives, herbalists, and army surgeons. He thought the most important quality of a good doctor was a willingness to learn new things. He published a treatise about miner’s health. It proposed some pretty radical concepts for the time. First, he articulated the difference between acute and chronic exposure to toxins. Acute exposure typically killed right away. For a more modern example, think of the so-called “Radium Girls.” They painted glow in the dark watch faces with newly invented radium pigment. They were in the habit of licking their paint brushes to make a finer point. Radium’s damage was fatal and quick.

Lisa Berry Drago: Chronic exposure can still kill, but the onset of symptoms is much slower, taking months and years. If somebody eats a lump of arsenic, well, so long. But it was possible to work successfully as a smelter for years, slowly inhaling small amounts of arsenic fumes every day. Eventually this kind of chronic exposure catches up, but it’s a lot harder to recognize along the way.

Alexis Pedrick: Paracelsus emphasized that what was happening to the miners and metalworkers was not a generalized internal imbalance, brought on from overwork, or an upset of the bodily humors. Instead, it was a direct result of their toxic environment, which was directly attacking specific parts of the body in specific ways. This in itself was a pretty controversial idea, even if it seems obvious to us now.

Lisa Berry Drago: Unfortunately, since his treatise wasn’t published until after his death, he didn’t get much of a chance to work towards changing mining conditions, even if he did have some useful ideas.

Alexis Pedrick: For miners, he recommended changes to their diets that would help their organs process toxins more efficiently. He also thought that regular baths and sweats would get toxins out of the body faster. For mine owners, he argued for more ventilation to prevent fumes from building up, and to keep the damp, sticky air more breathable. His emphasis on prevention rather than treatment alone was pretty forward thinking.

Lisa Berry Drago: So why didn’t Paracelsus’s case study change things? There are a few reasons. One is that making improvements to mines took money and time, which not every mine owner was willing to spend. As well as expertise, which not every mine owner was interested in seeking out. And frankly, besides workers’ complaints, there’s no real pressure on them to make changes. Early modern political systems weren’t really set up to address labor issues at this scale.

Alexis Pedrick: Maybe the world just wasn’t ready for Paracelsus. Attacking ancient knowledge like Galen’s bodily humors didn’t exactly make you popular with the other physicians. The medical system was invested in maintaining the status quo, and Paracelsus was too radical.

Lisa Berry Drago: Even when he did make it and was finally appointed as a professor at a medical college in Basel, his own colleagues ostracized him. They made fun of him. They refused to give him space to lecture on campus. Somebody even circulated a poem mocking his real name, Theophrastus, by calling him Cacophrastus. Caco, as in doodoo. Doodoophrastus. Yeah.

Alexis Pedrick: Now he’s remembered as a medical crusader. As a doctor he charged rich patients an arm and a leg for treatments, but he usually treated the poor for free.

Lisa Berry Drago: Maybe it was his class status that made him conscious about these things. For whatever reason, he had a perspective that a lot of his more privileged and secure colleagues didn’t share. Or at least not right away. It took over a century, but someone did come along who shared Paracelsus’s interest in hazardous work.

Alexis Pedrick: And his name was a lot shorter. Bernadino Ramazzini.

Chapter Three: Putting the Pieces Together.

Lisa Berry Drago: Paracelsus’s work is one of the first true case studies in occupational health. He digs deep into the material, and gets accurate, detailed descriptions of cause and effect. But his writings didn’t turn into major change for workers, and they didn’t really jumpstart bigger studies of occupational diseases either.

Alexis Pedrick: What was really needed now was someone who could get other doctors on board. And who could help establish the scale of the problem. Because of course it wasn’t just miners. Lots of trades were dangerous.

Lisa Berry Drago: That’s what Bernadino Ramazzini found out one day as he was idly watching a worker clean out a cesspool near his home in Padua. The year was around 1690, and Ramazzini was a professor of medicine at the local university. He was a well respected physician and a scholar, with a lot of wealthy, powerful clients, and a lot of admiring students. From a society standpoint, pretty much the opposite of Paracelsus.

Alexis Pedrick: It was purely by chance that he happened to be watching a cesspool cleaner at work. Cesspools, or privy pits, were the combination toilet garbage dump of the early modern world. They had to be regularly cleaned and kept from overflowing for obvious reasons.

Lisa Berry Drago: While Ramazzini watched the cesspool cleaner at work, he noticed he was moving quickly. Too quickly to be careful. In fact, he was rushing through the job, even making careless mistakes. When Ramazzini stopped over to talk to him, he asked, you know, why didn’t he take his time a little more? Why didn’t he do things right the first time, what was the rush? It was a cesspool, it wasn’t going anywhere, hopefully.

Alexis Pedrick: But the worker told him that saving time was more important than anything else. Cesspools cleaners who worked slowly, and therefore spent the longest time down in the pits, had an alarming tendency to go blind. This guy wasn’t taking any chances.

Lisa Berry Drago: Ramazzini was shocked. It was probably his first conversation with a cesspool cleaner ever. He started looking into eye diseases and other illnesses they had. And then he started looking into other kinds of hard labor. And on, and on, and on from there.

Alexis Pedrick: Ramazzini was actually the ideal person for this kind of work. He had a passion for organization and cataloging. Written medical knowledge was still in a piecemeal state at this time. Researching to find a single diagnosis could involve dozens of different kinds of texts.

Lisa Berry Drago: Ramazzini created a lot of new lists and indexes of diseases for his students to use like textbooks. One of them was a collection of the kinds of illnesses and injuries suffered by working people. He covered everything from repetitive strain injury, suffered in almost every field from carpenters and dock workers to secretaries and accountants, to the more toxic exposure suffered by, you guessed it, miners, cesspool cleaners, and chemical workers.

Alexis Pedrick: A lot of the material he gathered was firsthand. He visited tradesman shops and watched them go about their daily routines, noticing how they moved and strained. But for some of the most dangerous trades, Ramazzini didn’t have the opportunity to study them in person. There were no active mines near Padua, and it’s unlikely he ever visited one. Instead, he borrows information about miners diseases from earlier authors, including Paracelsus.

Lisa Berry Drago: In a way, Ramazzini was a perfect bridge between Paracelsus and the future of occupational health. Because to get to modern occupational medicine, and the labor regulation that goes with it, you need different sets of knowledge and different kinds of skills.

Alexis Pedrick: First, you need an in depth case study, as modeled by Paracelsus. Then comes the collector and compiler of information, Ramazzini, so that you can start to see the bigger picture. Then, finally, you need someone who will have all the tools to turn information into action.

Lisa Berry Drago: And that someone was Alice Hamilton. Chapter Four: Hull-House and the Reform of Work.

Alexis Pedrick: The state of work at the end of the 19th century was … not great. Let’s just say that factory workers were exposed to an unbelievable array of toxins, hazards, and indignities. And they typically faced them all for poverty-level wages.

Lisa Berry Drago: The problem of poverty, and how to alleviate it, was a major focus of social reform movements, especially in industrialized Chicago, Illinois. One of the leading voices came from Hull-House, a center at the heart of the settlement movement. A progressive activist movement aimed and understanding and eradicating poverty. The people who lived at Hull-House were fully integrated into the poor, working class and immigrant neighborhoods that they served. They lived there year-round. They set up and staffed family medical clinics, they taught free language and skills classes, they hosted social clubs, conducted home visits, and even sheltered victims of domestic violence.

Alexis Pedrick: At the same time, they conducted research into the causes of poverty and suffering, with the goal of advocating for social reform. They pushed for fair wage laws, better factory conditions, and an end to child labor and political corruption.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: Hull-House is just this focus for all kinds of new women activists. There are economists, there are social workers, there are educators, there are labor organizers, there are fair wage activists. There are sociologists, there are doctors, there are birth control advocates. It’s this incredibly rich group. It’s this incredibly rich environment that is really trying to look at how society can be changed. From a fairly bottom up kind of direction.

Lisa Berry Drago: Mary Mark Ockerbloom is a scholar, researching the histories of women in the sciences. And she used to be the Wikipedian in residence at the Science History Institute. She studied Hull-House, and in particular, she studied the life and career of Alice Hamilton. A medical researcher and epidemiologist who spent a decade of her life there.

Alexis Pedrick: Alice Hamilton was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1869, but she lived long enough to see the moon landing in 1969. As a young woman, she earned a medical degree and went on to advanced studies in pathology and physiology. She would eventually become one of America’s first great clinical researchers in occupational medicine.

Lisa Berry Drago: For Hamilton, Hull-House was a spiritual home. And it’s also the place where her life’s work began.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: When Hamilton first gets to Hull-House, uh, she does a little bit of everything. She teaches English, she teaches art. She operates a well-baby clinic, and she starts to see the effects on workers’ health, particularly of what are referred to as the dangerous trades. Ones that involve exposure to carbon monoxide, that involve exposure to lead. And she becomes increasingly interested in occupational injuries, in illnesses, and in epidemiology.

Alexis Pedrick: Like how Paracelsus lived and worked in mining towns, Hamilton’s life in a working-class neighborhood in Chicago exposed her to the horrific health problems of factory workers. Day after day she heard complaints like deteriorating joints, lost teeth, weakness and muscle spasms, and other signs she recognized as chronic toxic exposures.

Lisa Berry Drago: Hamilton’s a highly trained scientist by this point, so she knows she has to start tracking her cases and finding their origin points. But that’s easier said than done, because even at the start of the 20th century, occupational medicine in the United States simple doesn’t exist.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: The first thing to understand is nobody actually knows what processes a lot of these different businesses are using, or what’s involved in the work. And generally, nobody’s been paying attention and tracking any of this stuff. So the first thing she has to do is start figuring out who’s working in the dangerous trades and where are they working.

Lisa Berry Drago: The issue at stake is workers go into the factory and come out sick. To fix that problem, we need to understand what’s actually happening inside.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: And she does all kinds of things, she follows men walking around on the streets who look sick. She talks to peoples’ wives, she talks to their friends, she goes to hospital emergency rooms. She looks for smokestacks and signs of industrial pollution in the neighborhoods and tries to figure out what kinds of work are being done inside. She gathers information painstakingly. Homes, union halls, bars, hospitals, dispensaries, factories, and each of those visits gives her a chance to get more gossip about other places.

Lisa Berry Drago: There’s actually a term for this kind of research. It’s called shoe leather epidemiology. For the soles of the shoes that get worn down in tracking all of this information.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: She’s this incredible combination of detective, scientist, investigator, journalist, and public policy advocate.

Lisa Berry Drago: By 1910, Hamilton is a medical investigator for the state of Illinois. She writes a report on industrial hazards to workers, and it results in the first worker’s compensation laws in Illinois. By 1915, that leads to the passage of occupational disease laws in many other states.

Alexis Pedrick: As a medical investigator, Hamilton’s job now included making formal visits to factories. She tracked cases of illnesses and deaths and made recommendations about improving working conditions. One of her major studies focused on the effects of lead poisoning, and some of the things she describes having seen in person at these factories are pretty disturbing. Like coating bathroom fixtures with lead powder while wearing no protection.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: And she’s figuring out that that’s what’s going on, so one of the things she says later that she’s really proud of is having figured out that actually this particular area of industry, um, you know, making these bathtubs and things, was in fact a dangerous trade. And that people were at risk there.

Lisa Berry Drago: Lead was a known poison if ingested, but the effects of things like breathing lead fumes or lead powders, of the danger of having lead dust deposited on clothes wasn’t totally understood. One of the important things Hamilton’s studies established was clinical signs of toxic exposure, standards and measures that other researchers and other doctors could use.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: She doesn’t necessarily have diagnostic tests that she can use, so she uses clinical signs. With lead poisoning, with chronic lead poisoning, one of the things she looks for is a bluish black line along the, the gums of the, uh, the workers. Next to their teeth. And, and that’s something that she uses as a standard indicator so that she can measure the diagnosis of lead poisoning. And with lead, she showed that lead accumulated in bones and tissue. It remained there, it didn’t … It wasn’t just metabolized and excreted off. So, she was able to show that lead was actually much more dangerous than it had previously been assumed.

Alexis Pedrick: You probably won’t be surprised when we tell you that throughout all of this work, Hamilton encountered pretty serious resistance from factory managers and owners. A lot of them thought that as long as nobody died literally on the job, they were treating their workers just fine. Others knew that they had problems but tried to keep things under wraps.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: She also has to watch out for the fact that people are lying to her. They’re misdirecting her, they’re, they’re trying to fake her out. There’s one point where she visits a plant, and a worker’s wife tells her that the ceilings were torn out and the sick men were sent home before she came to visit.

Lisa Berry Drago: There was also the issue of her gender. Nearly all of the factory workers, managers, and owners she interacted with, not to mention government officials and policy makers, were men. Hamilton was routinely ignored and underestimated. But being underestimated was something Hamilton learned to use to her advantage.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: Descriptions of her say that she was very slight, she was attractive, she was very gentle, gentle mannered, a lot of the time she was … She’s been described as almost fragile in, in appearance. People did not expect a hard edged negotiator under that soft exterior. And I think … Yeah, I think Alice Hamilton definitely knew how to, how to work that.

Alexis Pedrick: Hamilton never lost sight of her goal. To push for policy change. So, not only did she submit all of her research to the Illinois government commissions, she went directly to factory owners and showed them the evidence.

Lisa Berry Drago: The surprising thing is she was often pretty successful in getting them to make changes.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: She seemed to have been an amazingly effective communicator. She had this ability to interact with people from widely different backgrounds and see them as real people and connect with them. And to tell them things they didn’t necessarily want to hear without alienating them. Um, part of it was that she approached people with the expectation that they would act in good faith. She uses that belief that they could do the right thing to get them to do the right thing. Um, she’s quite willing to shame people into doing the right thing if that’s what works.

Alexis Pedrick: Hamilton’s tireless spirit and her connections at Hull-House and in state government had huge impacts.

Lisa Berry Drago: Based on her studies, the Illinois legislature passed one of its first worker safety laws in 1911. The law required factory owners to limit chemical exposure and conduct monthly health checks. It also made reporting illnesses and injuries mandatory. The idea was that by keeping track of hazards on the job, physicians and lawmakers could get a better sense of what the dangerous trades actually were. In turn, they could create new standards and regulations around chronic exposure levels. They could require protective equipment and clothing, and so on.

Alexis Pedrick: We should also note that labor unions were a major force for change during this period. They helped track statistics about workplace injuries, and used those numbers to drum up membership, advocate for new labor laws, and put pressure on factory owners.

Lisa Berry Drago: Occupational health was well on its way to becoming an established field. In 1919, Harvard University created its first Department of Industrial Medicine, and Hamilton was an obvious choice for a hire. In fact, her appointment to the program made her Harvard’s first ever woman professor.

Alexis Pedrick: Except even though Hamilton was invited to join the faculty, she was never actually welcomed into Harvard life. When she retired after decades of service, she was still at the rank of assistant professor.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: She is definitely still an outsider, and, and in spite of the fact that she’s having this impact, you know, people don’t necessarily like her or respect her for that. Uh … Even when they have to listen to her.

Alexis Pedrick: Hamilton was barred from attending sporting events or socializing on campus with the rest of the all-21` male faculty. And there were other even pettier cruelties.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: She was explicitly uninvited from sitting on the stage with the other faculty at commencement. Year after year. They would send her an invitation to commencement with … personally to her, with a little note on the bottom that said, “And yes, we’re not allowing to sit on the stage.” Um, and, and it’s just … like I’m amazed that she actually stayed there til 1935 when she retired. I … because it can’t have been pleasant.

Lisa Berry Drago: Sound familiar? It did to us, too. Though their actual life stories couldn’t be more different, Paracelsus and Hamilton do have certain things in common. Both of them spent years of their lives doing on the ground research, living right alongside the people they studied. They were scholars seeking out scientific truth, but they were also compassionate physicians.

Alexis Pedrick: And they were both pushed to the margins in one way or another. Ignored by colleagues, treated like radicals.

Lisa Berry Drago: But being outsiders, or listening to the outside perspective like Ramazzini, may have been key to why and how these three people became founding figures in the history of occupational medicine. It gave them a different vantage point to see old problems in new ways.

Alexis Pedrick: Remember, even ancient Romans knew that miners got sick. Sometimes it’s not a question of having the data, it’s a question of perspective, and of caring.

Mary Mark Ockerbloom: She’s coming in from outside, she’s coming in from someone who’s trying to immerse herself in the experience of people who are not part of the dominant power structure. That is a huge key to Hamilton’s success, is, is she’s going out and she’s bringing in these perspectives, um, from a wide, wide range of people that she’s talking to from different backgrounds, from different experience, and she’s bringing them together. So yeah, absolutely, bring-bringing in diverse perspectives, bringing them together is absolutely critical to coming up with better ideas, better plans, better decisions. And she knows that.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Five: So What Now?

Lisa Berry Drago: Alice Hamilton passed away in September of 1970. But just a few months later, President Richard Nixon signed the Occupational Safety and Health Act into law. Many of the regulations and guidelines it established were based on standards and methods that she had pioneered. Here’s Nixon himself at the OSHA singing ceremony in 1970.

Richard Nixon: And so it is a landmark piece of legislation. Probably one of the most important pieces of legislation from the standpoint of 55 million people who will be covered by it ever passed by the Congress of the United States. Because it involves their lives.

Speaker 6: In creating OSHA, Congress affirmed the right of every working man and woman to safe and healthful working conditions.

Speaker 7: They have not only the right to expect, it’s the law that they should be able to go to their work in their morning, give the employer so many hours for so much money, and be able to go home to their family that night the same way they walked in the door that morning.

Alexis Pedrick: In 1970, about 14,000 Americans died every year on the job. That’s the same number of Americans who died in 1968 in Vietnam, at the height of the war. Today, the average annual number stands closer to 4500. Understanding workplace hazards means preventing workplace deaths.

Lisa Berry Drago: Unfortunately, millions of workers in the US and around the globe still endure unsafe conditions. In 2015, Wire Magazine broke a story on Chinese factory workers’ exposures to carcinogenic chemicals like benzene and anhexane.

Alexis Pedrick: Many of these factories produce goods for American tech companies. In the US, benzene is classified as a known carcinogen, and highly regulated. So in a way, the harm was just outsourced.

Lisa Berry Drago: While some companies responded to the story by banning those chemicals in their factories, others insisted they could be used safely given proper gear and low exposure. But even Paracelsus knew about the dangers of low but repeated exposures. One of his most famous sayings was, “Those dose makes the poison.”

Alexis Pedrick: And if you need an even more recent example, how about the essential workers in the era of COVID-19?

Lisa Berry Drago: We like to call them heroes, but many of them say they really feel like hostages, trapped in suddenly much more dangerous jobs, overworked and underpaid. And offered very little in terms of safety gear. They can’t social distance because they’re essential. But you don’t hear an echo of disposable in there, too?

Alexis Pedrick: As we here at Distillations love to remind you, science is a human endeavor. Doing science and medicine is wrapped up in our very human ideas about what science is, who should benefit from it, what’s worthy of study and action and what isn’t.

Lisa Berry Drago: For occupational medicine to emerge, we had to decide collectively that worker health was important enough to study, to track, to organize around, and to legislate to protect. It took a long time to get to where we are today, and we obviously have much further to go.

Thanks for listening to this episode of Distillations.

Alexis Pedrick: Remember, Distillations is more than a podcast. It’s also a multimedia magazine.

Lisa Berry Drago: You can find our video, stories, and every single podcast episode at Distillations.org. And you’ll also find podcast transcripts and show notes.

Alexis Pedrick: You can follow the Science History Institute on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for news and updates about the podcast and everything else going on in our museum, library, and research center.

Lisa Berry Drago: This episode was produced by Mariel Carr and Rigo Hernandez.

Alexis Pedrick: And it was mixed by James Morrison.

Lisa Berry Drago: The Science History Institute remains committed to revealing the role of science in our world. Please support our efforts at ScienceHistory.org/givenow.

Alexis Pedrick: For Distillations, I’m Alexis Pedrick.

Lisa Berry Drago: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago. Thanks for listening.

Alexis Pedrick: Thanks for listening.