Though they lived decades apart, Adolphe Dessauer and Abdelwahhab Azzawi share similar stories. They were both esteemed physicians who faced violence and persecution in their home countries. They both sought refuge abroad and found safety, only to find themselves facing a new struggle—getting permission to practice medicine in their new homes.

Dessauer, a Jewish doctor, fled Germany for the United States in 1938. Azzawi, a 36-year-old ophthalmologist from Syria, found asylum in Germany in 2015. Both men’s lives were spared through the generosity of their new countries, but they had to struggle to give back in the most meaningful way they could—by sharing their medical expertise.

In 2016 every American Nobel laureate in science was an immigrant. And it wasn’t just that year; U.S. winners often are born abroad. Yet as global an enterprise as science has become, navigating bureaucracy and straddling boundaries seems to be as difficult in the 21st century as during World War II.

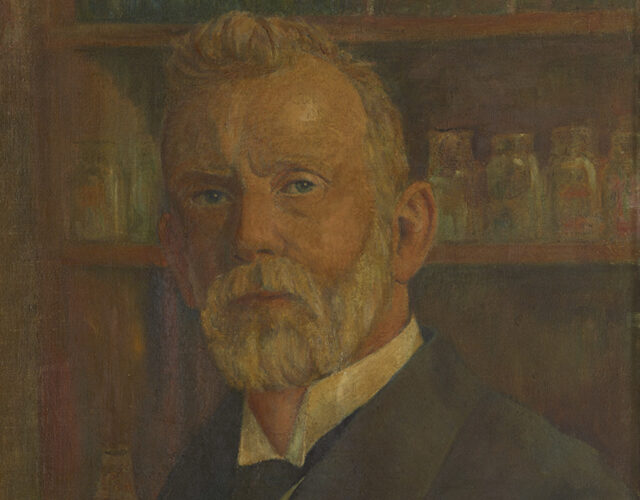

This podcast was inspired by a painting once owned by Adolphe Dessauer. The painting was part of the Institute’s Things Fall Apart exhibition.

Credits

Hosts: Michal Meyer and Bob Kenworthy

Producer: Mariel Carr

Associate Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Reporter: Catherine Girardeau

Audio Engineer: Catherine Girardeau

Our theme music was composed by Zach Young

Additional music is courtesy of the Audio Network

Transcript

Refugee Doctors: Escape is only the first challenge

Michal: Hello and welcome to Distillations, the science, culture, and history podcast. I’m Michal Meyer, a historian of science and editor in chief of Distillations magazine, here at the Chemical Heritage Foundation. Bob is away, but he’ll be back for the next episode. In 2016 all the science Nobel Prize winners from the United States were immigrants. That’s one of the highest accolades a scientist can ever receive. And it wasn’t just that year, U.S. winners are often immigrants.

John Hildebrand >> Science is a global enterprise. It’s not a national enterprise, and we benefit enormously by these connections and talent and brain power that comes here.

Michal: That was John Hildebrand, a neuroscientist and a member of the prestigious National Academy of Sciences. Sometimes scientists cross national boundaries in search of greener pastures, other times it’s a matter of life and death. In this episode of Distillations we bring you two stories of doctors who escaped turmoil in their home countries. Their stories tell us about

their bravery, but also remind of about the contributions they’ve made to their adopted countries. The first story starts with a painting.

Chapter 1: The Painting

Elizabeth Berry-Drago >> You know, I hate to say it but it’s the sort of painting you might walk past at first if you were in a portrait gallery—

Michal: That’s Elizabeth Berry Drago. She’s a research fellow at the Chemical Heritage Foundation.

Berry-Drago >> You know, it’s not a particularly large painting, it’s not a particularly elaborate setting. The sort of surface textures aren’t particularly lush or anything like that. It’s not what we think of elite portraiture or sort of famous striking portraiture that we’re used to seeing, like great generals or fabulous society women or something like that.

Michal: It’s a portrait of a man gazing just past the viewer. He has tired blue eyes and grey beard and moustache. His brow is slightly furrowed. He looks serious. The dim light in the painting and the muted earth tones add to the subdued feeling. The painting itself isn’t so noteworthy, but the man in it is. It’s Paul Ehrlich, and he was one of the most famous German-Jewish scientist and doctors of the early 20th century. He won the Nobel Prize in 1908 for his work in immunology and is most famous for his discovery of a successful treatment for syphilis. In Germany streets are named after him, statues honor him, and his face was once on the 200 Deutsche Mark banknote. The painting doesn’t tell any of that. But if you look at it in a different light—and I mean that literally, if you look at it with a bright, angled light—a bigger story comes into focus.

Berry-Drago >> Raking light puts the light directly at the side so you can see topography, the sort of textured surface of the picture, to give you a better look at the little rises and valleys that it has.

Michal: The painting is currently on display at the Chemical Heritage Foundation as a part of a museum exhibition called Things Fall Apart. The museum team told us about the ridges on the right side of his face and nose as if it had been repaired.

Berry-Drago >> Some of the things that immediately stood out to us were that there’s a ridge, what looks like it might be a seam from where the canvas was stitched back together. It’s really like a mountain valley. And a couple other sections where you really start to see like, “whoa, there’s a dramatic texture change.” It’s highly indicative of the damage it was done to it.

Michal: You’d never know just by looking at it, but on the night of November 9, 1938, Nazis punched and ripped apart the painting during what became known as Kristallnacht—or “night of the broken glass,” when thugs went into Jewish homes and businesses to loot and destroy while the authorities turned a blind eye. Kristallnacht was a signpost on the road to the Holocaust. The Nazis killed dozens of Jews and damaged and destroyed hundreds of paintings owned by Jews that November night and thousands more during the war. But this portrait of Ehrlich survived.

Chapter 2: Paul Ehrlich

Michal: Adolphe Dessauer was a German Jewish doctor vacationing in Italy in 1927 when he met the painter, Franz Wilhelm Voigt. He learned that Voigt had made a portrait of Paul Ehrlich years earlier for a magazine, and he asked the painter to make him a copy. Dessauer had worked under Ehrlich in Frankfurt, and he admired him greatly. So he hung the painting in his apartment in Nuremberg. He treasured it. It was one of two paintings he owned. Dessauer’s son Rolf says the first one was of a lobster.

Rolf Dessauer >> No. He was not an art collector. He liked to be reminded of Paul Ehrlich.

Michal: That’s Rolf Dessauer. He was born in Germany and also went into science. He went on become a chemist specializing in dyes, and worked for DuPont in Delaware. Rolf tells us about the affinity his father felt for the man in the painting.

Dessauer >> I assume he was just very impressed by Ehrlich or I guess he also felt perhaps he wanted people to know that he had some kind of a connection to Ehrlich from the time he worked in his institute, but I regret that I never talked to my father about his time like that. It’s a shame.

Michal: To Adolphe Dessauer, and many other German Jews, Paul Ehrlich was a symbol of Jewish scientific achievement—at a time of ingrained anti-Semitism in Germany. His success did not come easily.

Weissberg >> First of all, he worked at the Charite in Berlin.

Michal: That’s Liliane Weissberg, a professor of German literature and part of the Jewish Studies program at the University of Pennsylvania. The Charite is a large teaching hospital in the German capital.

Weissberg >> …And could not obtain a regular professorship at the university, but second of all he was slighted at every level in his actual research. He helped and collaborated with Emil von Behring on the diphtheria immunization and treatment, but was pushed out of the story of the success, so then it was known that Behring did it all.

Michal: Behring went on to win a Nobel Prize in 1901, without any credit given to Ehrlich. Ehrlich was unfazed and moved to Frankfurt where he became the director of a research institute. That’s where he came up with his famous “magic bullet” theory. Magic bullets were what he called a kind of ideal therapeutic agent that could target an organism that causes disease, and kill it, without harming anything else.

Clip from Doctor Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet >> The Magic bullet. Mankind’s faintest weapon. Forged in the white fires of one man’s courage.

Michal: That’s a clip from the 1940 biographical film, Doctor Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet. Ehrlich kept working despite of the pervasive anti-Semitism of the early 20th century. And in 1908 he won the Nobel Prize for discovering his magic bullet, a treatment for Syphilis. He would have had an easier time if he had converted to Christianity. It’s what a lot of other German-Jewish scientists did back then.

Weissberg >> But there’s something like civil courage. He is one of the few who refused to convert. And to be frank, one doesn’t really know why. Because there is not a reason of obvious religious commitment. This was not an Orthodox Jew who said, “I’m not going to leave my religion. I’m sticking to it,” and so on. This is a German patriot who did not keep the Jewish faith that clearly, who would probably not have lost that much in changing to Protestantism, even just on paper, which is what thousands of people did at that time. But he refused to, and that refusal made him a hero or symbol of the members in the Jewish community.

Michal: Paul Ehrlich died in 1915 long before the Dessauers commissioned the painting now hanging in Philadelphia, and also long before the Nazis stripped people like him of their professions and humanity. His gravesite, remarkably, remained undamaged during the Nazi regime, which destroyed many symbols of Jewish life.

Weissberg >> It’s the gravestone with two large columns: something that is bringing together the exuberance of the classical tradition with the heroic, and whatever. On top of one of the columns is a Magen David, a Star of David. On top of the other is the Asclepius staff of the medical profession. And you look at them, and you say, “What is going on? The Magen David, the Star of David, and

the sign of the medical profession have equal value on top of Greek columns. How do I get this together?” That kind of fantasy of what life could be: a profession fulfilled with an identity fulfilled, and an identity that would combine Jewishness, Germaness, and the medical profession. That was a very brief moment when people thought that was possible.

Chapter 3: The story of the Dessauers

Rolf Dessauer >> Around two o’clock in the morning I heard a lot of noise and I was sort of wondering and so I woke up and I went into the hallway of our apartment and I saw my mother talking to a number Stormtroopers and I thought “my god. What’s going on here?”

Michal: That’s Rolf Dessauer, Adolphe Dessauer’s son. He was 12 years old when Nazi’s broke into his second story apartment in Nuremberg during Kristallnacht, on November 9, 1938.

Rolf Dessauer >> They smashed anything that had glass. The picture that we had, they took off the wall and sort of slashed it. People those days didn’t have refrigerators, but they had sort of a pantry and then upended that. I mean, you can’t imagine it. It was just as though somebody wanted to make everything that looked nice look ugly and they did that.

Michal: They tried to destroy all the Dessauer possessions, including the painting of Paul Ehrlich.

Dessauer >> Well, the painting was just slashed to ribbons. It was like somebody took a knife and cut it into strips.

Michal: It would have been easy to lose all faith in humanity. But the next day Rolf Dessauer says an “Aryan looking man” showed up at their door and told his father, Adolphe, that he wanted to fix the painting. Three days later he came back, and with the painting. It was as if it had never been torn apart.

Dessauer >> And my father wanted to pay him and he said “No. No. We wanted to show you that not everybody was sympathetic to what the Stormtroopers did.” And we never saw him again.

Michal: Soon after Kristallnacht, the Dessauers left Germany. They settled in Washington Heights, New York. A neighborhood full of European immigrants. They chose New York because it was one of only five states that allowed immigrants to practice medicine. In 1941 the Nazi government revoked Adolphe medical license, adding insult to the earlier injury. But it didn’t matter because he was already in New York and had passed the state board exam that allowed him to practice medicine in the United States. The Dessauers couldn’t bring all their possessions, but they made sure to bring the painting. And after Adolphe’s death, the painting hung at Rolf’s house in Wilmington, Delaware, until he gave it to CHF three years ago.

Michal: Lianne Weissberg says Ehrlich’s life story is powerful.

Weissberg >> He became a symbol for those who were persecuted by the Nazis, and that’s why you have the holding on to the picture. The way the picture became a symbol of value and identity that had to be kept, immigrated with, restored, cherished. It is the painting and the object that becomes a token of German-Jewish life and exceeds the history of Paul Ehrlich.

Chapter 4: The Syrian Doctor

Michal: Like Adolphe Dessauer before World War Two, Dr. Abdelwahhab Azzawi was forced to leave Syria and get relicensed as a doctor in a foreign country. But Azzawi immigrated to Germany in 2014, rather than from Germany in the late 1930s. Reporter Catherine Girardeau brings us his story.

Catherine Girardeau: Like most reporters, I start every interview by asking my guest to introduce himself, to define himself, if you will. For thirty-six-year-old Abdelwahhab Azzawi, this turned out not to be a simple question.

Abdelwahhab Azzawi >> I am a human being. I cannot just say I am Syrian or I am Arab. So my name is Abdelwahhab Azzawi, I am a father, I have two kids, a family. That’s the most important thing for me. Then I am a doctor also, an ophthalmologist. I am a poet also.

Girardeau: Azzawi is also an atheist, and back in Syria, had been a political activist before radical Islamist forces entered the conflict around 2013 and the situation devolved into chaos. Being an atheist, and activist, put him in the crosshairs of both the Syrian regime and the Islamic State, and he was forced to flee, not once, but twice. Azzawi grew up in Deir Ez Zor, a city in eastern Syria, during a time of political upheaval. In 2010, pro-democracy protests were gathering steam in Syria, and Azzawi and his wife took part. President Bashar al-Assad announced conciliatory measures, such as releasing political prisoners, and the protesters believed they might have a chance at real government reform.

Azzawi >> This was our chance. We were in the streets with people. To make a real revolution.

Girardeau: But instead of continuing democratic reforms, the government cracked down.

Azzawi >> We had no real chance against the violence. We don’t have any other option and people should defend themselves.

Girardeau: And the pro-democracy uprising failed, leaving radical Islamists to fill the void.

Azzawi >> At the end, it’s just like a siege from both sides: the regime and the radical Muslims, they stole our revolution and we were out.

Girardeau: Although the street protests were over, Azzawi continued to agitate for reform by writing newspaper articles. His work was censored. He began to be harassed.

Azzawi >> They investigated about me so many times, they took my email, my Facebook.

Girardeau >> Did they threaten you also physically?

Azzawi >> Yeah, one time. But you know they don’t make it directly. They send people. You can be beaten in the street and you don’t know who, why. But I understand this.

Girardeau: Although Azzawi believes the men who beat him were sent by the regime, he chose to stay in Syria. But then in June 2012, the conflict intensified.

Azzawi >> This was really aggressive. They attacked the people.

Girardeau: Islamic State forces raided a medical center Azzawi ran. He should have been there but —

Azzawi >> I was late about one hour.

Girardeau: His tardiness may have saved his life. If he had been there he would have been executed. Deir Ez Zor was now under siege. Continuing to practice medicine meant putting himself in danger on a daily basis. Azzawi often had to drive through sniper fire – from both sides.

Azzawi >> At the end it’s clearly, it’s terrible danger for my family. So I’ve decided to move out. I have no other choice. I was a little bit shamed. So this means we were defeated. This my feeling,

Girardeau: At each stage of his long journey to safety, Azzawi’s been propelled by different, and distinct, motivations.

Azzawi >> In Syria, it was my dreams. We had so many dreams before the revolution you know? We had dreamed about this revolution. We dreamed about this revolution as a beautiful woman. We wrote about this revolution. But afterward we discovered this revolution is an awful creature, an awful being, you know? I tried to defend my dreams, but I failed, just like many people. I failed.

Girardeau: With his dreams shattered, Azzawi and his family moved to Yemen, one of the few Gulf countries that was still accepted Syrians, where he’d managed to secure a post as head of the Ophthalmology department at a hospital in Tarim. Unlike Syria, which had been a diverse society with many religions and ethnicities …

Azzawi >> In Yemen it’s another story, it’s a radical Islamic society. It’s not like Syria. I said I’m just a doctor. I didn’t say that I’m a writer also – it’s very, very dangerous to say that I’m a writer. I am a secular also. So I just tried to hide behind the medicine.

Girardeau: But after a year, the threats started again. Someone had discovered his political writings online. He was questioned about why he hadn’t celebrated Ramadan.

Azzawi >> I’m atheist. People know that I’m atheist. So I cannot participate in on all their religious rituals.

Girardeau: Fearing for his family’s safety, he began laying the groundwork to leave Yemen.

Azzawi >> I had to escape this hell. It’s not related to my dreams. It’s not related to my point of views against the regime. It’s just to save myself and my family.

Girardeau: He decided to try to go to Europe as a visitor. As a doctor he figured he could get in if he was presenting at a medical conference. He submitted a paper to a handful of conferences in various countries. His plan was to apply for asylum in whichever country he landed in. This back door route is one way foreign professionals enter European countries. The invitation to the German conference arrived first.

Azzawi >> I got the visa, after a long process – I have to prove so many things – then I was in Germany.

Girardeau >> You were you were granted political asylum in Germany – is that right?

Azzawi >> It’s some way or another political. But I’m not quite sure… to be honest I didn’t ask. For me, this not the point here. The point is I should start once more. I should work. I should start a new life. This is the point.

Girardeau: What kind of asylum he received really didn’t matter to Azzawi; he just wanted to work in his field as a doctor. I should say that Germany has been the most generous of the

European countries when it comes to taking in refugees. By the end of 2016 they’d taken in about 890,000, many of them Syrians. But in a country where following the rules is almost a religion, refugees face serious obstacles, from learning the language to healing from trauma, to figuring out how to purchase a bus ticket. Azzawi was safe in Germany but building a life was harder. He entered a Kafka-esque world of bureaucracy, red tape and endless delays. (0:34)

Azzawi >> So the first difficulty is…I came to Germany. I cannot speak German, you know? There’s no way to learn German!

Girardeau >> So as a refugee you were not given access to a German class?

Azzawi >> At first, it’s forbidden! You cannot work, you cannot learn. You can not move from your from your town.

Girardeau: At least not until you’re processed through the system, as a refugee. All refugees are eventually expected to learn the language, but Azzawi wasn’t willing to wait for permission to start. With his family still in Yemen, he desperately needed to establish himself so he could get them out – and provide for them once they arrived.

>> Sound of German lesson from “Deutsch Für Dich”<<

Azzawi >> I started to study German alone. This was the only chance. I can speak English well so. I studied German with English.

Girardeau: Azzawi didn’t have Internet at his refugee hostel but he managed to download an online German course and learn on his own. By this time, with the help of the international

writer’s organization PEN International, he had moved from a small town on the Polish border, where he and many other Syrian doctors were sent initially, to the slightly larger town of Senftenburg.

Azzawi >> Then I had some difficulties with the foreign office in Senftenburg. They made everything terrible for me. They did not accept easily to bring my family. Everything was so slow and bureaucratic.

Girardeau: While he was waiting, Azzawi figured out it would be easier to get a medical license in the German state of Saxony, so, again with the help of friends and contacts, he moved to Dresden to start the process.

Azzawi >> So many papers. They asked me for so many papers, and this is a little tricky because you cannot ask me for papers when I’m a refugee, so how can I contact my government?

Girardeau: The Syrian government wasn’t interested in sending papers to dissidents who’d left. Somehow, he managed to get the papers together. But there was another catch. Without a promise of work, Azzawi couldn’t apply for his medical license.

Azzawi >> I had so many problems with the job center because jobs center also make everything so slow. Then I found a position in Giessen University as a surgeon. I should say I got a good chance. We are grateful. Germany gave the Syrians or all the refugees a wonderful opportunity.

Girardeau: During Azzawi’s asylum application process, a civil war broke out in Yemen in early 2015. With the help of his brother, who was also in Yemen, Azzawi’s family went into hiding–until Germany granted them visas to come join Azzawi. They made it to the airport–just before Yemen’s civil war shut them all down. Again, Azzawi’s accidental timing saved lives–this time, the lives of his wife and two young children.

Azzawi >> The airports were closed three days after my family travelled.

Girardeau: Based on his, and other Syrian doctors’ experience of long waits and red tape, Azzawi wishes Germany could fast-track these professionals into the workforce.

Azzawi >> They need a lot of doctor in Germany, you know this? It could be so easy you got a lot of refugees, who are doctors. We are good surgeons. And medically we got so many certificates, we are highly qualified.

Girardeau: Finally employed in Germany, Azzawi’s struggles are now of a different sort: being respected. Being seen. He feels compelled to show his German colleagues that he’s worthy.

Azzawi >> I need to prove myself here. You know I do my best. I do my work more than others. I understand this, sometimes more my colleague I do it for myself, to afford better circumstance for my family and to prove myself.

Girardeau: Even though he’s so grateful at Germany’s generosity towards refugees, he longs for more understanding, and to be seen as an individual.

Azzawi >> There’s people against refugees, there’s the other side people who fight for refugees. Both sides don’t know anything about these refugees. Not all Syrians are Muslims. The Germans treat them as Muslims, not as Syrians.

Girardeau: Azzawi says the problem extends to the media, which tends to present Syrians as victims of war, heroes, or radicals.

Azzawi >> These people are normal people in terrible situation and they got this problems…

Catherine >> You’re an eye doctor, you help people see better. What do you wish people could see?

Azzawi >> To see themselves first of all, then they can see each other.

Azzawi >> Sometimes you need a lot of time. To see yourself as you are, not as you should be. This needs a lot of time, this need more than just eyes.

Girardeau: Azzawi has started taking his own advice. Since he’s been in Germany, he’s begun writing poems again, using his changed perspective to try to see himself, and the rest of humanity, from a little bit of distance.

Azzawi >> I took a lot of time just to try to answer these questions. I am not finished. I could not find my answer yet.

Girardeau: This is one of his recent poems.

In blindness

The terrifying stab of hope is painful as beginnings.

The shivering lip drops,

And hearts bite their owners.

We were not prophets or victims,

We were forgotten like dry tree trunks.

Blind hatred colors inside like a screaming garden. The careless compass points Indifferently

The deaf compass is unable to listen to the noisy blood that’s everywhere.

Girardeau: For Distillations, I’m Catherine Girardeau.

Chapter 5 Conclusion

Newsclip >> As we mentioned this is all happening on the heels of president Trump’s executive order suspending refugees from entering the United States. The suspension applies to these Muslim-majority nations. Syria, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, Somalia, Sudan and Egypt.

Newsclip >> President Trump tonight vowing to dramatically cut legal immigration by prioritizing English-speaking immigrants with skills that help grow the economy.

Newsclip >> Major news tonight: President Trump ending the DACA program saying congress must now decided the fate of the so-called dreamers. 800,000 young, undocumented brought here by their parents.

Michal: Those are some of the most recent headlines coming out of the white house when it comes to refugee and immigrant policy. They have people like Dr. John Hildebrand worried. He is a neuroscience professor and a foreign secretary for the U.S. National Academy of Science.

Hildebrand >> It prevents us from having the benefit of having great people coming into this country. Something that has elevated the quality of life in this country greatly over the last couple hundred years. And now we are shutting the door for many of those people. For me it’s a horrifying prospect. It’s totally unjustified based on what I think is just flat out ignorance and prejudice. It’s a shameful chapter in the history of this country and that’s my opinion.

Michal: Distillations is more than a podcast. We’re also a multimedia magazine.

Michal: You can find our videos, our blog, and our print stories at Distillations.org.

Michal: And you can also follow the Chemical Heritage Foundation on Facebook and Twitter.

Michal: Our producer is Mariel Carr.

Michal: Our associate producer is Rigoberto Hernandez.

Michal: This episode was reported by Catherine Girardeau. She also mixed this episode.

Michal: Our theme music was composed by Zach Young.

Michal: For Distillations, I’m Michal Meyer, thanks for listening.