Our producer is pregnant. For the past nine months, people have asked what her birth plan is, which to her seems like asking what kind of weather she had planned for her wedding day. “All of a sudden, my life was full of these terms: natural, medicated, doula, epidural, and it quickly became clear that there was a great debate—and I was supposed to choose a side.”

We wanted to know when this controversy started and why comedian Amy Schumer is joking about sea-turtle births. So we talked to Lara Freidenfelds, a historian of sexuality, reproduction, and women’s health in America, and learned some surprising things about our nation’s early childbirth practices.

Freidenfelds also shared her views about why a growing number of women are opting for unmedicated births, while Amy Tuteur, a retired obstetrician and the author of Push Back: Guilt in the Age of Natural Parenting, tells us that once upon a time, all births were natural—and a lot of mothers and babies died.

Credits

Hosts: Michal Meyer and Bob Kenworthy

Guests: Amy Tuteur and Lara Freidenfelds

Reporter: Kristin Gourlay

Producer: Mariel Carr

Associate Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Seth G. Samuel

Music courtesy of the Audio Network

Transcript

1. INTRO: (Natural) Childbirth is Trendy

>>AMY SCHUMER CLIP >>

“Have you guys figured out your birth plans?” “Oh of course.”

“All I know is I want a natural birth and NOT an epidural.” “Oh my—of course not. It’s better for the baby.”

“My midwife suggested a sea turtle birth.” “What’s that?”

“Oh it’s when you give birth on a beach, and you dig a small hole, and kick sand on the baby and see if it crawls into the ocean or into your arms. It’s better for the baby.”

“You know, I would be careful though, with a midwife. Even though they’re not technically doctors they still have some medical training and I just don’t trust Western medicine at this point. That’s why I’m having my baby on the highest mountaintop in Tibet. As far from real medical help as is humanly possible. My doula is a sherpa.”

“So Mena, what’s your birth plan?”

“I don’t know…I think when I go into labor I’m just going to go to the hospital and do what the doctor says.”

MICHAL: Hello and welcome to Distillations, the science, culture, and history podcast. I’m Michal Meyer, a historian of science and editor of Distillations magazine, here at the Chemical Heritage Foundation.

BOB: And I’m Bob Kenworthy, CHF’s in-house chemist.

MICHAL: That clip from the Comedy Central show, Inside Amy Schumer pretty well sums up what we’re talking about today—childbirth. Specifically the revival of the so-called “natural” childbirth movement— and the controversy surrounding it.

BOB: And it has nothing to do with the fact that our producer is nine months pregnant.

BOB: Early on when Mariel told people she was pregnant a lot of them asked her what her birth plan was.

MARIEL: To me it sounded like someone asking what kind of weather I was planning for my wedding day. And all of a sudden my life was full of these terms—natural, medicated, epidural, doula, midwife, OB—and it quickly became clear that there is a great debate—and I was supposed to choose a side.

MICHAL: So we wanted to figure out how and why this “natural” trend started—and when things like sea-turtle births came in vogue. But we realized to do so we needed to go back to not only the beginning of the natural childbirth movement, but to the beginning of childbirth in America. So we did. And we learned some surprising things.

BOB: But first independent radio producer Kristin Gourlay is going to tell us a personal story about the birth of her son.

2. FEATURE: I Can’t Get to You

MICHAL: Kristin Gourlay is a Connecticut-based health care reporter. Her son’s birth was a surprisingly traumatic event. We’ll hear her story, “I can’t get to you” in a moment. But first, Kristin, welcome. Tell us what kind of birth you were planning – if anyone can really, truly plan a birth!

KRISTIN: Right, well, no one ever knows how a birth is going to go. But for me, I had a normal pregnancy all the way through. No complications. I was monitored for all the typical things – blood pressure, weight gain, and my growing baby was monitored for growth and development. Everything was normal and on schedule. I was thinking that because my pregnancy was uneventful, my birth would probably be, too.

So, my plan was pretty simple: a vaginal birth, and to hold out against pain medicine for as long as possible, so that I could really experience the birth. I worried an epidural would leave me too numb. But I also knew I might not be able to bear the pain. And I knew certain things could go wrong, but my sense was that they were rare. And no one really prepared me for the fact that I might need to throw my birth plan out the window.

BOB: Can you tell us more about your decision-making process? How did you decided you wanted an un-medicated birth?

KRISTIN: Sure well, I think there’s this cultural pressure for mothers to be strong, that you have to really “experience” a birth to be able to say you’ve really gone through it. That’s baloney of course. But I was under this impression that I might regret having taken medication and avoided the pain. And as you’ll hear, I wound up needing a c-section after laboring for a while. And I almost felt as though getting a c- section was failing somehow. As if I had done something wrong and that’s why I failed to get this baby out. But it turns out I had no control of what actually went wrong.

MICHAL: OK, Kristin, let’s hear your piece. Then we’ll come back to you after to hear how this experience changed your perspective.

KRISTIN: Great.

July tenth, 2013. I’ve just gotten out of bed. It’s about eight o’clock. I’m getting ready to go to work. My water breaks.

“Um, babe?”

“Really? I guess this is happening.”

You don’t seem in any rush to pop out right then, so we have breakfast. Your dad and I. We get in the car.

And then.

“Hon? I’m not going to make it.” “You mean…?”

“I mean I can’t make it to the hospital in the city. We have to go to the local hospital. Fast. This baby is coming now.” The cramps double me over. You want out.

Everything until now had been normal. Normal tests. Normal sonograms. Normal normal. “All normal.”

By ten a.m. I lay in a hospital bed, trying to push you out. “Come on, hon. You can do this.”

But you just don’t want to descend. I push. You stall. I push. You grow fainter. I push. You seem to be disappearing. That’s when they start scrubbing me down, shaving me. Prepping for an emergency c- section. Just five more minutes! I ask. The nurses say no. He needs to come out now.

“The patient was born on 7/10/13 at 15:01 p.m. via c-section secondary to failure to descend…”

I’m on the operating table. I feel a great pressure down on my abdomen. Then a great lightness. Sudden cold. They pull you out.

Then… Nothing.

No screaming baby.

No “congratulations.” No “it’s a boy!”

I feel like I’m under water. Can’t hear anyone.

“At 15:02 the baby was brought out to the resuscitation table and was found to have a heart rate of 110. His color was blue.”

You are blue.

“There was minimal respiratory effort and no tone. Stimulation was attempted and suction was also attempted. Positive pressure ventilation had been started by 30 seconds of life.”

Where’s my baby? What happened to my baby? Is he okay? I’m an open wound on this table.

You’re gone. The room is silent. Just the swoosh of lab coats. Voices muffled on the other side of a pane of glass.

“Heart rate by two minutes of life was below 80 and non-palpable and thus CPR was started at 15:04.” 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

“CPR was continued until 15:15.”

Someone comes and whispers in my ear, “Ma’am, your baby’s having a little trouble breathing.” What?

“Between 15:04 and 15:15 intubation was done and a UVC line was placed. Infant developed spontaneous respiration and a faint cry was heard around the tube.”

What’s happening?

I get to hold you once, for a few minutes. “He’s not stable yet,” they say.

So they take you in an ambulance to a bigger hospital with a NICU. I’m not allowed to go with you. There’s no room for me in the ambulance. No beds open for me in the big hospital. Only 40 minutes away but so far. I stay alone in a room at the little hospital. I feel like clawing my way out, past the IV pole, past the front desk nurse, out the door, down the road into the night.

Then grandma arrives.

“I saw my daughter in a state of misery…”

They tell me over the phone you’re hooked up to monitors, an IV. Your blood oxygen dips sometimes but you’re improving.

I need to get to you more than I’ve ever needed anything. I want to rip off my bandages, call a taxi, and speed to you.

There’s no room they kept telling me. I’m losing my mind I say.

We’re taking good care of him. He’s in good hands. They’re not mine, I said.

Then finally – I’m released. Grandma and I race up to the big hospital. I throw open the curtain and…. “That moment when you first saw him…”

There’s a picture of us – of me, seeing you for the first time since they took you away in the ambulance. My face is cracking into sobs. My heart is breaking, knitting back together, breaking again.

Your little hand, bandaged to an IV. The tiny monitors stuck to your chest. You’re finally in my arms. You’re perfect. I’ll sleep in the chair by your bassinet. I’m not leaving without you.

BOB: Thanks for sharing your story, Kristin. Now, we should say your son Magnus is three years old today and he’s fine. But were you told why he was born not breathing?

KRISTIN: Not exactly. It wasn’t very clear at the time and in the confusion no one was really explaining anything to me. But for this piece, I went back and read all the medical records. And my best

interpretation is that my son’s respiratory system was filled with fluid they had to suction out—much more fluid than normal.

MICHAL: So Kristin, obviously the birth of your son did not go according to your plans. How did that transform the way you think about childbirth and even the possibility of controlling how birth goes?

KRISTIN: It completely opened my eyes to the fact that I think as a pregnant woman you have to open to the possibility that so many things can go wrong. I understood very quickly that interventions like

medication helped save my baby’s life, and for me it meant the difference between being able to cope and not having the strength to go on. There’s this loss of control once the process starts. And I just

couldn’t have begun to imagine the variety of things that could go wrong.

BOB: Did it change your views on medicated vs. un-medicated birth?

KRISTIN: Well, honestly, before the birth I didn’t really think it was a big deal. I thought maybe I could power through labor without any drugs. But I went from my water breaking to being more than halfway dilated in less than a couple of hours – really fast, really hard labor, and it was incapacitating. I was

begging for that epidural. Now I see childbirth as something that’s at once incredibly simple, but incredibly complicated all at once, because so many things can go wrong.

MICHAL: Luckily it seems you got great emergency medical care.

KRISTIN: Absolutely. I feel so lucky to live in a country with access to this kind of medical care. I’ve also thought about how lucky I am to live in this century, rather than, say, the middle ages, when something like what happened to me and my son Magnus would most likely have killed Both of us. Mostly I think if I ever had another child –which I’m not planning on – I would keep an open mind about my birth plan.

That way, an emergency c-section or needing an epidural right away is not as much a surprise as a possibility you’ve considered. It’s such a personal thing, but that’s what I take away from the experience. That and how lucky we are.

BOB: Kristin, thank you so much for talking to us.

KRISTIN: Thanks for having me.

3. Childbirth is Dangerous. And Painful.

AMY: The truth is that childbirth is dangerous. It is dangerous. No amount of wishing it wasn’t dangerous changes that.

MICHAL: This is Amy Tuteur.

AMY: Childbirth is inherently excruciating. It is so excruciating that it actually impressed the people that wrote the Bible thousands of years ago.

MICHAL: Amy is a retired obstetrician and the author of Push Back: Guilt in the Age of Natural Parenting. She started delivering babies in the mid-80s and gradually saw more and more women requesting un- medicated or “natural” births. She was blown away by how many of them were then devastated when things went differently than they’d imagined.

AMY: One thing that really struck me is that I would deliver a healthy baby to a healthy mother, and I would make rounds the next day and ask her how she was doing, and she would be all upset. I would ask why and she would say, “I’m a failure. I had an epidural.”

BOB: Women opting for un-medicated or “natural” births are a small but growing minority. Some of them deliver in hospitals without pain medication. Another way to measure the trend is to look at how many people opt for midwives instead of doctors. The midwife vs. doctor rate grew from 3% of all births in 1989 to 9% in 2013.

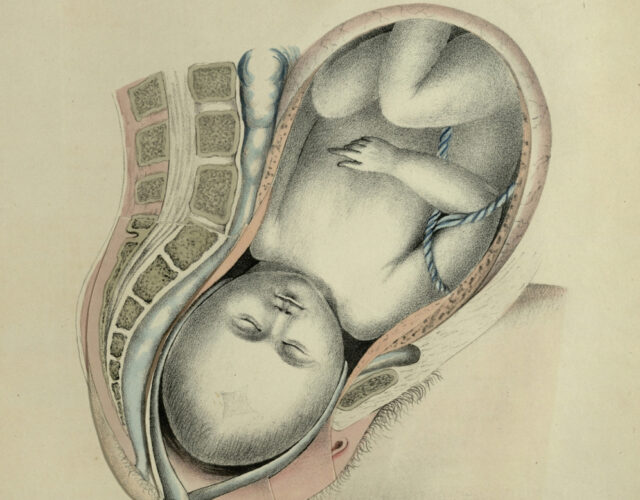

4. Childbirth used to be even more dangerous and painful – a short history of childbirth in America

LARA: In colonial times women basically expected to have children starting from when they married until the end of their reproductive years. Women at that time had an average of 7 or 8 children.

MICHAL: This is Lara Freidenfelds, a historian of women’s health, sex, and reproduction in America. From the colonial era all the way through the 1930s every woman had a decent chance of dying in childbirth.

LARA: The maternal mortality rate was about 1 in 150 to 200. That meant for a woman who is going to have eight children, there is a 1 in 25 chance of dying in childbirth sometime in your life.

AMY: All you have to do is go to a colonial cemetery. You’ll find that they are filled with young women and babies.

LARA: Women sometimes put their affairs in order before a birth, fearing the worst.

MICHAL: There was actually a whole genre of prayers just for childbirth.

Oh my lord God, I thank thee with all my heart, wit, understanding, and power, for thou hath vouchsafed to deliver me out of this most dangerous travail.

Up I go, step over you

with a living child, not a dead one,

with a full-born one, not a doomed one.

BOB: Until the middle of the 19th century midwives delivered babies—not doctors. And births were social events, filled with female friends and neighbors.

MICHAL: But by the 1850s middle-class women started calling doctors to deliver their babies.

LARA: The hope was that doctors would make it safer, and also that they could relieve the pain that was in itself difficult, but also at the time, really might signal that you were having the kind of problem that would lead to death.

BOB: So when doctors introduced chloroform and ether to the birth room, women welcomed them.

5. Childbirth got less painful and less dangerous. But there were tradeoffs.

AMY: Women viewed pain relief in childbirth as an incredible miracle. They loved it. They wanted it.

MICHAL: But there were problems. Some people died after inhaling chloroform.

BOB: Both chloroform and ether are volatile liquids that can induce temporary comas when inhaled. They depress the central nervous system, so they can be used as anesthetics. But inhaling either one is as dangerous as sniffing glue. They’re Both toxic—chloroform even more so than ether. And they can create permanent reactions, including death. Luckily, by the 1910s doctors found a pain relief option

that wouldn’t kill you—twilight sleep.

MICHAL: Though it does sound like something out of a horror movie.

AMY: The way that twilight sleep works is that women receive some medication for the pain, actually not very much, and a lot of medication to make them forget what happened.

BOB: Twilight sleep used a cocktail of the drugs morphine and scopolamine. Scopolamine is mostly used for motion sickness, but it also can also cause memory loss. This combo would dull pain and cause short term memory loss.

MICHAL: One the drawbacks of twilight sleep was that it could lead to feelings of detachment. Women would wake up with a baby, but no memory of how it got there. Doctors were also using general anesthesia at the time, which was not only dangerous, but also led to those same disconnected feelings.

AMY: So the search was on for ways to deal with the pain without having the risks of general anesthesia.

BOB: By the early 20th century doctors had made birth less painful, but there were still safety issues. Unlike midwives, doctors treated sick patients as well as pregnant women, so they spread infections unintentionally. But after the 1930s…

AMY: There was really no contest. Hospitals were much safer, and childbirth went from about 5% in the hospital in 1900 to about 95% in the hospital by the end of the 1950s. The other thing that people don’t tend to talk about that made hospitals extremely appealing is that having a baby in a hospital was a vacation. A lot of these women: they were farmer’s wives and they had to do chores when they were home, and they had to take care of their children. To go to the hospital and have them wait on you hand and foot for a week, people thought that was just fantastic.

MICHAL: A clip from a 1950s educational film called “Labor and Childbirth” makes birth in that era look quite calm and pleasant.

>>At the admissions desk you will be asked a few questions, but only a few, and then you will be taken to the delivery room to prepare for the delivery of your baby. When you reach your room you’ll get undressed, put on a hospital gown and roll into bed. >>

MICHAL: But things were a little paternalistic.

>>There is a table with sterile drapes to cover your abdomen, legs, and buttocks. There will also be various sorts of anesthetics, for example a continuous caudal anesthetic set. A saddle block anesthetic set. And there will be gas available. Some mothers, perhaps you, may want a certain kind of anesthetic. Feel free to ask for it. But by all means leave the final decision to your doctor.>>

BOB: And they weren’t always so pleasant. This is Lara again.

LARA: It became almost like factory birth. It wasn’t just that they were knocked out, it was that a woman arrived at a hospital and was separated from her family, put in a room by herself. She was given an enema. She was shaved. A lot of women found that humiliating and sort of shocking. Then, the doctor did an episiotomy which is a cut in the perineum so that they could put in forceps and pull the baby out because once you’ve done that much anesthetic, it’s very hard for a woman to push the baby out herself. That was considered a normal birth in the ’50s and ’60s.

6. Things started getting more natural. But they were still run by men.

MICHAL: When natural childbirth advocate Grantly Dick-Read wrote a book called Childbirth Without Fear in 1942, people saw it as a solution to a system that had stripped women of power.

LARA: When women were looking at the appeal of someone like Grantly Dick-Read saying “you don’t have to have it like this, you actually could give birth without this business. It’s not just that they were knocked out. That was an important part, but that there were a whole bunch of routine interventions that left women feeling worse after birth than they thought maybe they could and that often felt humiliating.

MICHAL: And many people today still see Grantly Dick-Read as a champion for women. But Dick-Read himself actually had very different intentions. Amy Tuteur was shocked at what she found out while researching her book, Push Back.

AMY: He was basically a eugenicist who was obsessed with the problem of race suicide. He really felt that the UK was being taken over by brown people.

BOB: He thought white women of the so-called better classes weren’t having enough children because they were weak, and scared of the pain of childbirth.

AMY: He told women they had been socialized to believe that labor was painful. Primitive women, by which he meant women of color particularly black women, they had painless labors.

Well, that wasn’t true. He just made that up. His view was that the mother was the factory, and by education and care, she could be improved in the art of producing and caring for children.

MICHAL: The other founding father of the natural childbirth movement was Fernand Lamaze, of the Lamaze technique, which uses psychological conditioning and breathing exercises instead of pain

medication. You’ve probably seen it humorously depicted on any number of sitcoms, like this clip from Roseanne.

>>Oh god this is all your idea! I hate you! Oh god it hurts! Breathe!

It helped me before but it’s not helping me now Dan!

That’s ‘cause you’re not doing it, come on honey breathe! >>

BOB: Lamaze was invented in the Soviet Union after WWII. They didn’t have access to the same effective pain relief as the west, but they still needed something to give laboring Soviet women.

AMY: You didn’t need any money to have it because it was all a form of Pavlovian conditioning.

MICHAL: The idea was that just like Pavlov’s dog and his bell, women could learn to associate pain relief with patterned breathing. Everyone thought it was great. Except for the pregnant women.

AMY: Lamaze came to France, and interestingly, it was never very successful in the Soviet Union. It wasn’t especially successful in France either.

BOB: But when Both Grantly Dick-Read’s philosophy and Lamaze crossed the Atlantic they were welcomed by American women who were fed up with the medical system.

MICHAL: And though people now use Grantly Dick-Read’s book and the Lamaze technique to prepare for un-medicated childbirth, neither Dick-Read nor Lamaze were opposed to medical pain relief themselves.

AMY: They just thought it should be up to the doctor when women got pain relief.

BOB: The search for an effective and safe method of pain relief finally came to an end in the 1970s.

AMY: Epidurals were a huge breakthrough.

MICHAL: They’re a kind of regional anesthesia.

AMY: Kind of like Novocaine when you get dental work.

BOB: The nerves at the base of the spine are bathed with anesthetic, so every nerve leading out of the spinal cord is bathed in it too, numbing the lower half of the body.

AMY: They allowed women to achieve the desire to be awake and to not experience agonizing pain and to be in control. Because being in control was such an important thing for so many women. Not surprisingly.

MICHAL: So it seems like the story could end here. But it doesn’t. And people have different ideas about why.

7. So why is there still so much controversy?

BOB: So why is there still so much controversy?

LARA: From the 1970s forward, I think the natural childbirth movement has evolved and doesn’t mean the same thing to every woman who comes into it.

MICHAL: Some women, like the ones from that Amy Schumer sketch, want nothing to do with epidurals, doctors, or hospitals.

LARA: Then there were people who just meant, “Hey, can we not do stuff to me unless I say, please?”

BOB: But some think it’s gone too far.

AMY: I often say that the surest sign of privilege is when you refuse something that another woman in a part of the world that is not so developmentally fortunate would walk ten miles to get it. There’s a lot, a lot of women who would give a great deal to have an epidural. It really marks you out as special when you say ‘I don’t need that.’

MICHAL: This is Amy again.

AMY: There is no question that the natural childbirth movement accomplished great things. But when it had done those things, it had to move the goal posts.

AMY: It was about choice prior to the 1980s. Now it’s about specific choices. If the natural childbirth movement was about choice, they would be out there demanding easy access to pain relief, and marching on behalf of maternal request C-sections, and basically expanding women’s autonomy in which ever way women wanted it to go. However, that’s not what has happened.

AMY: The holy grail of the natural childbirth movement is what they call unhindered, un- mediated vaginal birth. In my view, that is where they really went off the rails.

BOB: Of course, a lot of women see it differently. And think that in 2016 we’ve simply traded in the factory births of the 1950s for a different kind of factory birth.

LARA: M any women still felt that they were not actually getting to make the decisions in the birth room, and felt like…you take one thing away, you add another thing on.

MICHAL: One of these “add-ons” is the increased likelihood of having a c-section. Today 1 in 3 American births are now cesareans—many of them unplanned. When necessary they’re life-saving.

But they come with their own set of complications and it’s clear they’re not all needed.

AMY: Oh yeah, the c-section rate is too high. It’s easy to say that. The problem is that we know we are doing unnecessary c-sections, but don’t know which ones are the unnecessary ones.

BOB: Some people point to electronic fetal monitoring as a culprit. It’s a way for obstetricians to measure whether or a not a baby is in distress during labor.

AMY: Prior to the advent of fetal monitoring women would have a completely normal labor, everything would be seen to be going great, and a baby would be delivered and the baby would be dead. And no one understood why.

BOB: But it has a high false positive rate.

AMY: That means that if the fetal monitor shows that the baby is fine, the baby is almost certainly fine. However, if the fetal monitor shows that the baby is in distress, that’s not

necessarily true. The difficulty that obstetricians face is that they have an imperfect tool to prevent a really serious problem.

MICHAL: So if you’re a doctor delivering a baby who might be in terrible distress—do you do an emergency c-section? Or do you take the risk? Fears of lawsuits, the relative ease of performing c- sections, and just plain old ethics make most doctors choose c-sections.

LARA: We have remarkable control over birth outcomes. It is astounding how well we’ve done. That in the last couple of decades we’ve come to a point where it is almost like we think we can get to an endpoint with that. We can get to perfection. We feel that if we could just get it right, if we could just do a little more, we’d get it perfect. At the same time, women are seeking fulfilling birth experiences. Not just the experience for the woman, but it is a moment in your child’s life that feels really critical and important and meaningful It’s this urge. It’s this promise. And also this fear of guilt and failure if it doesn’t go perfectly.

AMY: I think that the stakes are very different for obstetricians and for mothers when they talk of perfection. Perfections means a healthy baby and a healthy mother. For natural childbirth advocates, it means an aesthetic experience on par with a wedding. That birth is a piece of performance art, and that you have to do it just right or you should feel bad about what you have done.

MARIEL: I guess part of what’s fueling the movement and controversy is that we’ve actually come so far. Those old diary entries and prayers showed women who just wanted to survive—and have their babies survive—and of course they wanted to get through the pain. But they didn’t have the luxury of worrying about c-section complications, or feeling empowered, not to mention thinking about the quality of the experience itself. Now we have this sense that we can plan or control something that no woman in 1885 would have ever thought was controllable.

MICHAL: For Distillations, I’m Michal Meyer.

BOB: And I’m Bob Kenworthy.

BOTH: Thanks for listening.