The 19th century was a time of rapid technological leaps: the telegraph, the steam boat, and the radio were invented during this century. But the century was also the peak of spiritualism: the belief that ghosts and spirits were real and could be communicated with after death. Seances were all the rage. People tried to talk to their dead loved ones using Ouija boards and automatic writing. Although it might seem contradictory, it’s not a coincidence that this was all happening at the same time.

There have always been questions about life after death, but in the 19th century people found new ways to investigate them using these new cutting-edge technological tools. And part of it was that some of these new tools felt supernatural in and of themselves. The radio, the telegraph, the phonograph: these allowed us to speak over inconceivable distances, communicate instantly from an ocean away, and even preserve human voices in time and after death. But something else was going on in the 19th century. The people who were trying to figure out if we could really talk to ghosts were not just on the fringes; many of them were scientists.

Credits

Hosts: Alexis Pedrick and Elisabeth Berry Drago

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Music

“Lanterns Ascending” by Jerry Lacey.

“Shapeshifter” by Martin Klem.

“Behind that Door” by Farrell Wooten.

“First Sign” by Mahlert.

“Black Core” by Guy Copeland.

“Maximum State” by Ethan Sloan.

“String Quartet No. 3, Op. 41 Adagio Part 4” by Robert Schumann.

“Chronicles of a Mystic Dream” by Grant Newman.

“Deep Cellar” by Experia.

“Shapeless Inside” by Cobby Costa.

“Aquamarine” by Mahlert.

“Decomposed” by Philip Ayers.

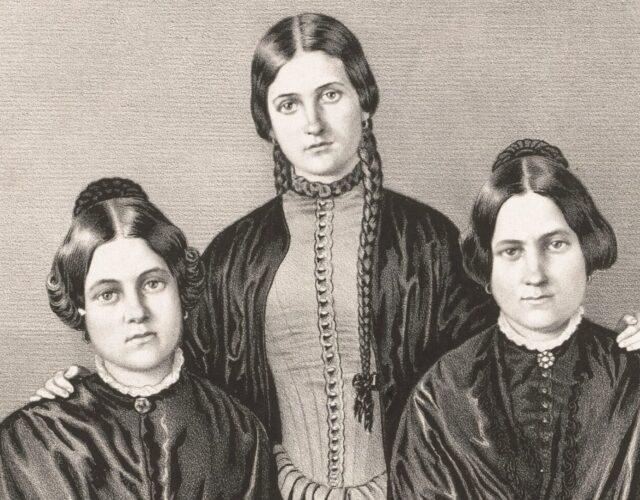

Special thanks to Charley Levin and Lena Kidd-Nicolella for their portrayal of Maggie and Kate Fox.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Resource List

Ghostland: An American History in Hunted Places

Speaking Into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication

Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death

Transcript

Alexis Pedrick: When you think about ghosts, something like this might come to mind.

Ghosthunters TV show: Is someone in here with us? Ghost Hunters is back, with a new team, better tech, and more answers. The lights were going on and off, these arms grabbed me, and knocked.

Lisa Berry Drago: Let’s figure out what the heck’s going on here. This is my favorite part of the night.

Alexis Pedrick: Ghost hunting shows are a whole genre. And they have three things in common. The goal, the method, and the outcome. The goal is almost always to prove that ghosts are real. The method is technology. And the outcome is always about keeping things open to interpretation. There’s never quite enough evidence to prove that ghosts are real, but there’s also never quite enough to prove that they’re not real. It’s always inconclusive.

These three ingredients for communicating with the dead help feed an inherent yearning to keep the door open, to what we’ll call the “what if?”

Lisa Berry Drago: Let’s start with the method. The technology that ghost hunters use is almost always inexact. If you ever watched a ghost hunting show, you’ve witnessed the ghost hunters trying to puzzle out what it is they’ve just recorded.

Ghosthunters participant: I hear a woman’s voice now. Ma? May possibly actually feel like she’s saying mom. I don’t think it sounds that American to me.

Ghosthunters host: Right.

Ghosthunters participant: I’m gettin’ mom.

Ghosthunters host: Yeah.

Ghosthunters participant: That’s what I’m gettin’ from it. But it could be Mary.

Lisa Berry Drago: And Colin Dickey, author of Ghostland, says this inexactness is on purpose.

Colin Dickey: What is most important is to get the signal to noise ratio up to a level where you can start interpreting the results. So if you have a highly-controlled experiment, you know, to determine if ghosts are real, you are much more likely, I mean, to get, you know, a negative response, you know, because you- you have eliminated the variables, so, you know, you’re not gonna get any kinda false positives.

Alexis Pedrick: Throughout history, if there was a new way to talk to your friends and family, people also used it to try and talk to the dead.

Colin Dickey: As a technology is- is invented, you’ll find people who see it as- as a means of connecting with the dead, or otherwise explaining our relationship to the dead.

Alexis Pedrick: Our story today begins in the 19th century. It was a time of huge and rapid technological leaps. The telegraph, the steamboat, the radio. But this era was also the peak of spiritualism, the belief that ghosts and spirits were real, and could be communicated with after death. Seances were all the rage. People tried to talk to their dead loved ones using Ouija boards and automatic writing. People were hungry to know what else is out there, beyond the veil of reality.

Lisa Berry Drago: Although it might seem contradictory, it’s not a coincidence that this was all happening at the same time. There have always been questions about life after death, but in the 19th century, people found new ways to investigate them, using these new, cutting-edge technological tools. And part of it was that some of these new tools felt supernatural in and of themselves. The radio, the telegraph, the phonograph. These allowed us to speak over inconceivable distances, communicate instantly from an ocean away, and even preserve human voices in time, and after death.

Archival: Thomas A. Edison, the inventor of the phonograph, has never before permitted his voice to be recorded for the public. Today, however, he has a message for you that is important enough to cause him to break his long-established rule.

Archival: This is, uh, Edison speaking.

Lisa Berry Drago: But something else was also going on in the 19th century. The people who were trying to figure out if we could really talk to ghosts were not just on the fringes or in the world of entertainment, like the people on Ghost Hunters. Many of them were scientists. This is Deborah Blum, a science writer and the author of Ghost Hunters.

Deborah Blum: Such an amazing period of time, when you get these truly brilliant, high-profile scientists engaged in this. You know, I- I mean, even Marie Curie, speaking of famous scientists, briefly, you know, did some experiments with this. We’ll never get that again.

Lisa Berry Drago: Today, we think of science and the paranormal as being incompatible, fundamentally opposite. But it turns out that science, technology, and investigations of the supernatural were entwined for a very long time.

I’m Lisa Berry Drago.

Alexis Pedrick: And I’m Alexis Pedrick. And this is Distillations. As silly as ghost hunting might seem to us today, at its heart, this story is about people searching for answers to life’s biggest questions. Who are we? What happens when we die? And what’s left behind? And what happens when we don’t get the answers we like, or when science can’t give us a conclusive answer?

Lisa Berry Drago: As you might expect, it gets a little messy. Chapter one: the annihilation of space and time.

Alexis Pedrick: In 1847, John Fox, his wife Margaret, and their daughters moved to the small town of Hydesville, New York. By the following spring, 14 year old Margarita, or Maggie, and 11 year old Kate, started to hear strange knocks, rappings around the house. After hearing these knocks every night, they finally got the courage to ask the rapper, “Who are you, and what do you want?”

Archival recreation: Hello? Who’s there? Is anybody there? Who are you, and what do you want?

Deborah Blum: They called the source of the mysterious rappings Mr. Splitfoot.

Archival recreation: Mr. Splitfoot? Are you a ghost?

Alexis Pedrick: This is Deborah Blum again.

Deborah Blum: And they started getting these pattern of messages. A- and you… and you can oversimplify this. One rap for yes, two raps for no. And they would ask questions and Mr. Splitfoot would answer them.

Archival recreation: Do you know what happened to the grocer? Are you real?

Deborah Blum: Then eventually, they would ask Mr. Splitfoot questions about other people, right? People would say, “Does he know my great-aunt?”

Archival recreation: Is my great-aunt’s spirit still with us?

Deborah Blum: And the answers were surprisingly real, right? So that people believed that these, uh, young girls, and- and ev-… you know, young girl’s the epitome of innocence, were actually talking to a dead man.

Lisa Berry Drago: Later that summer, John Fox and his neighbor were digging around the cellar of a house, and they found fragments of bones and hair. It was a dead body, which presumably belonged to the dead man the Fox sisters had been talking to, or so the story goes. Newspapers started writing about it. Phineas Taylor Barnum… that’s right, P.T. Barnum, got a whiff of this, and he thought he could put the sisters’ talents to use. So he brought them to New York City, to put them on display in his New American Museum.

Alexis Pedrick: The museum was open 15 hours a day, and hosted more than 15,000 visitors a day. People could pay two dollars to talk to the dead through the Fox sisters. Among their visitors were the novelist James Fenimore Cooper, the author of The Last of the Mohicans, editors of the New York Tribune, and the former governor of Wisconsin. The Fox sisters became 19th century celebrities. Every move they made was scrutinized and newsworthy.

Deborah Blum: I don’t think this says anything great, but in the way that the Kardashians, you know, are widely known, in- in the… in the way we say household name, Maggie and Kate Fox, who were known to, you know, be besieged by the Morse code of the dead, they got a huge amount of publicity. This is the 19th century, so it’s gonna be printed publicity, the penny dreadful newspapers, as they were called, and different magazines, and of that sort. But they were front-page news often, people knew who they were, people knew their names.

Lisa Berry Drago: Besieged by the Morse code of the dead. Ooh. The Fox sisters could have used any number of methods to communicate with the dead. They could have used mirrors or other reflective surfaces to try to see the dead. But instead, they used something very specific to the time. Morse code. Morse code had been around since the early 19th century, but it was only introduced to the average citizen thanks to the invention of the telegraph in 1844. That’s just four years before the Fox sisters were visited by Mr. Splitfoot.

Archival: Other methods of communication were slow and tedious. The telegraph was the only means of rapid communication. It was direct, it was fast, it kept pace with the nation’s expanding frontiers.

Lisa Berry Drago: Imagine the world before the telegraph entered it in 1844. People had never before experienced instant communication across long distances. Messages were carried by people, sometimes by birds. Not transmitted in the blink of an eye, without the sender of the message even being physically present. This is John Peters, the author of Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication.

John Peters: The 19th century is perhaps the single most revolutionary century in human history, in terms of technology. I know that sounds like- like a radical statement, but it’s kind of like you poured Miracle-Gro on the technological, so much is happening so fast. And it may seem funny that people get really excited about the telegraph, the photograph, the phonograph, and invested almost a messianic quality to them. But it- it actually isn’t that, uh, surprising in context, because, you know, the simplest way to talk about 19th century technology is, to take a line which they quoted incessantly, the annihilation of space and time.

Alexis Pedrick: So, when the Fox sisters began their tapping, they were actually tapping, pun intended, into the fact that people already understood Morse code as a kind of miraculous communication from elsewhere. If you could communicate across continents, across time zones, collapsing vast distances in an instance, then why couldn’t you communicate between the living and the dead?

Deborah Blum: I think the fact that people were familiar with this kind of tap-tap-tap signaling makes a lot of sense that you would then go on and say, you know, and now the dead are communicating, and patterns, not exactly Morse code, but in the same kind of rapping patterns.

Lisa Berry Drago: There was an accepted link between spiritualism and technology in the 19th century. We can see this in the kind of language that both spiritualists and technologists used. This is Peter Collopy, an archivist and curator at CalTech’s library who focuses on media technology.

Peter Collopy: So, the concept of, uh, spirit telegraphy was one of the ways that people talked about, um, speaking with the dead, the idea that the dead could actually be sending you a message in- in dots and dashes like Morse code. And similarly, the way that we use the word “medium” now draws from these- these 19th century resonances between these practices, so we can use the word “medium” now to refer to a person who channels the dead, or we can use it to refer to a communication technology by which we channel our own voices and images.

Lisa Berry Drago: In other words, as the term “medium” emerged, it applied to both the telegraph and to the person who claimed to speak with the dead. Same term, same essential medium, an almost magical way of communicating.

Of course, there are other forces at work besides the telegraph that contributed to the popularity of ghosts and spiritualism. Something big happened in the middle of the 19th century that fueled a widespread desire to speak with the dead: the Civil War.

Alexis Pedrick: The Civil War claimed over 700,000 American lives. It was an inconceivably large portion of the population at the time.

Deborah Blum: There tends to be, in the history of spiritualism, periods of deep upset and disorientation in society tend to also be drivers of interest of this. So in the United States, for instance, post the Civil War, you saw a huge upswelling of interest in spiritualism and questions about our ability to talk to the dead, driven both by the fact that a lot of people had lost loved ones, and wanted to be able to connect with them, and the fact that the Civil War itself shredded the fabric of society, so that a lot of the standard traditional institutions weren’t enough. People wanted there to be something more.

Alexis Pedrick: And when you mixed together startling technological achievements, national chaos, and huge death tolls, spiritualism starts to make perfect sense.

Lisa Berry Drago: When Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1878, the journal Scientific American described it as, quote, “making speech immortal.” That was exactly what tens of thousands of people were longing for, the chance to hear a loved one’s voice again.

John Peters: You know, in a sense, all recording media are cemeteries. The idea that you could record the dead, their minds, their thoughts, their words, their deeds, to live on, is a very ancient one. So if you read, you know, Homer, he’s singing the praises of great deeds on the battlefield of, you know, Achilles, for example. But, you know, writing does not preserve the voice of the dead. It preserves the words of the dead, and there’s a profound difference. And the idea that we could suddenly know what someone sounds like, and keep hearing their voice after they were dead, seemed particularly haunting.

Previously, to hear the voice of a dead person was the domain of magic, or sorcery, or something weird and haunted. So you can see how the, uh, phonograph has this patina of the uncanny.

Lisa Berry Drago: Thomas Edison’s phonograph originally had the ability to both record and play sounds using the same apparatus. He showed an early version of it to a few colleagues, and one of them was the engineer and later spiritualist, Oberlin Smith. Oberlin Smith, like our producers, was a bit of an audiophile, and a sound quality perfectionist. He loved the idea of the phonograph, but hated how noisy and gritty the recordings sounded. And he suspected that what caused it was friction between the needle and the record, when the needle passed physically over the record’s grooves.

Alexis Pedrick: So, he turned to magnetism. Instead of the needle having direct contact with the record, Smith proposed using an electromagnet that could hover over a magnetized record, creating the sound but avoiding the friction. He did some experiments to try and prove it was possible, but eventually abandoned the idea.

John Peters: But, about a decade later, he comes back to this idea in a theological context, and he publishes an article in the Andover Review, a theological journal, in which he suggests that the soul might be entirely physical, entirely within the sort of domains of physics, of matter and energy. He suggests that the soul might be some sort of durable chemicals, or it might also be magnetic, it might be a magnetic phenomenon that could be durable.

So, could you send a brainwave from one person to another in the same way that you could send a radio signal from one sender to another receiver? So this is kind of the, uh, context. I don’t think it’s crazy.

Lisa Berry Drago: Oberlin Smith has proved that cutting-edge engineers and researchers were thinking about their own inventions in spiritual terms. To him, it wasn’t a contradiction. There seemed to be an exciting potential in new tech, that it might unlock doors human beings had never been able to even rattle the handles of.

Alexis Pedrick: And as the century went on, the technological hits kept coming. Photography was invented in the 1820s, but it didn’t reach most consumers until decades later. Early cameras required long exposure times, so subjects had to sit still for several minutes. If you moved for even a second, the image would blur, and you’d look like a ghost. Hence, spirit photography became another popular, uh, medium.

Lisa Berry Drago: When early versions of the radio were described in print, people talked about human voices as literally traveling through the airwaves, or moving across an intangible space that was referred to as the ether, a kind of invisible fluid or field of matter that could conduct and carry electricity, radio waves, light, heat, and so on. Scientists were so excited about the possibilities of the ether that it opened up a whole new field of research.

Chapter two: psychical research.

Alexis Pedrick: The prevailing theory that the ether could carry light, magnetism, and radio waves within it was not a fringe belief. It had widespread traction in the scientific community. There was actually a group of scientists called psychical researchers trying to explore the full potential of the ether. They saw it as the ultimate unity of the physical and intangible.

John Peters: Psychical research is the effort to be scientific about spiritualist phenomena. That is, to try to study how it might be possible for there to be some kind of contact between the living and the dead.

Lisa Berry Drago: If you think metaphorically about science and spiritualism as existing on some kind of long slider bar or continuum, from data-driven investigation on one hand to more spiritual or philosophical meditations on the other, the psychical research folks would probably sit right at the middle.

Alexis Pedrick: And the American face of psychical research was William James, the so-called father of American psychology. He was born in 1842, and came from a well to do family of authors in New York City. And when authors, I mean Ralph Waldo Emerson was his godfather.

Lisa Berry Drago: Today, we define him as a psychologist. But he was also a trained physician who taught anatomy at Harvard. His most famous theories were all about the links between mind and body. He argued that the body reacts to events first, and then your mind contextualizes what happens later. Past experiences are therefore important, informing a person’s consciousness.

Now, this all sounds incredibly basic, but he’s one of the first to articulate these links clearly. And that’s why he’s considered a founder of what’s known as functional psychology.

Alexis Pedrick: But he was also the founder of the American Society for Psychical Research in 1884. Their goal was to prove the existence of telepathy. But, they were also interested in, well, everything we’d call paranormal today.

John Peters: James is a great waffler, if you put it unkindly, or, someone who is able to keep many thoughts alive at the same time.

Lisa Berry Drago: James believed in both the spiritual and the scientific process. It was his mission to reconcile them with evidence, which explains why he was so obsessed with a woman named Leonora Piper.

Alexis Pedrick: Leonora Piper was a respectable Boston mother of two, who claimed to hear voices from the dead. She delivered their messages through automatic writing. She’d go into a supposed trance, and write unconsciously, transmitting messages from the beyond. And she got famous for it. By 1910, she was paid $20 a sitting. That’s 500 bucks today.

Lisa Berry Drago: The story of how William James became fascinated with Piper goes like this. He goes to one of her seances, and she tells him details about his wife’s family that no one else should know. Information that wouldn’t be in the gossip columns. Family secrets, mundane little details of their lives. For James, these messages were evidence that Piper really did possess some kind of unexplained power.

John Peters: He’s not a snob. He’s willing to understand the, uh, human condition via all of its crazy forms, and these shows clearly play with that, um, desire. So James is always keeping the door open for a more humane, experiential, poetic, religious understanding of the human lot, along with the scientific one.

Alexis Pedrick: James wanted to test the limits of Leonora’s mysterious knowledge. He, and one of fellow psychical researchers, started by creating an impossible challenge for her. They gave her three locks of hair from three unknown donors, and asked Leonora to identify the owner of each lock of hair. And she did, correctly. James and his colleague were stunned, and wrote a paper about it. They also decided to spend even more time and money investigating mediums.

Lisa Berry Drago: Ultimately, James concluded that there was something meaningful in the Boston medium’s work. Within the fragments of her spirit messages and automatic scribblings, he believed there were authentic communications. And in his mind, it was precisely the role of the psychical researcher to help interpret the signal from the noise.

John Peters: What James is always doing is wavering on this question, does the soul survive death? This is the big question [laughs] that every human has had to deal with it one way or another, is the soul immortal? And James knows that he can’t answer it.

Alexis Pedrick: Interpreting signals from the noise is a recurring theme in the history of spirit communication. They’re always garbled and incomplete messages.

John Peters: So seances are actually festivals of communication breakdown, even though the idea is that the medium is gonna connect you between the living and the dead, in fact, most seances are really fragmentary.

Lisa Berry Drago: Remember the Fox sisters? They benefited from their fragmentary answers. The dots and dashes they tapped out were, by necessity, simple, and that left their meanings open for interpretation.

Alexis Pedrick: William James didn’t see this as a problem. In fact, he embraced it. He saw the messiness of spirit communication as an opportunity for psychical researchers. It was something that needed to be studied.

John Peters: This is always the, uh, question about religion and poetry, but also about bamboozlement, is that we humans need the what-if, because our existence is structurally uncertain. I mean, it’s almost like it’s designed to be uncertain. I mean, no one knows what’s happening after we’re dead. No one can really say what the meaning of this world is, or how we came here, or what we’re doing. I mean, those questions are just inherently open. To deny that is to really deny something profound and fundamental to who we are.

Lisa Berry Drago: Some of James’ colleagues didn’t see things the same way, including G. Stanley Hall, the first president of the American Psychological Association, and one of James’ former students. Hall was a dropout of the American Society of Psychical Research, and he became one of their harshest critics.

Alexis Pedrick: Hall targeted James’ favorite medium, Leonora Piper, as a subject of his research. His goal? To prove that everything about her was a sham and a lie. Now, Hall was a skeptic. He believed that science’s role was to eliminate mystery, rather than to explore or embrace it.

Deborah Blum: You know, you have this sort of interesting tension in the scientific community. All the facts of the world are so, and we have the power now rather than religion, and we’re gonna tell you what’s real and what’s not real, right? Um, and this was a sorta throwing down of the gauntlet, as they used to say, right, to organized religion. Y- you know, you’ve been telling people how the world works, and now it’s our turn. And so some people in science really felt there was a mantle of responsibility with that.

Alexis Pedrick: He started by trying to prove that Leonora Piper’s trances weren’t trances at all, and his tests weren’t exactly what we’d call humane and responsible, or even scientific.

Deborah Blum: If you’re just pretending to be in a trance, and I can prove you’re not in a trance, then by association, everything else is also false, right? And they tried all kinds of different things, and they ratcheted it up, right? Essentially, they would just try different methods of pain, right? They dropped bitter things in her mouth, they burned her, they pinched her. She had scars from some of this. They were never able to bring her out of the trance by those methods, right?

Now, either she had some unique trance-like abilities that we don’t understand, or she was genuinely in some sort of trance, right? Many of the mediums we’ve talked about, or haven’t talked about, you know, were proven to be all-out frauds. But no one was ever able to fully do that with Leonora Piper. That’s not me passing judgment on what was real and what was not real, that’s just me saying that no one was able to fully debunk her.

Lisa Berry Drago: Despite being burned and pinched, Leonora never did come out of her trance during the tests. Did that prove she was indeed a legitimate medium? We officially can’t answer that question. What we can say is that Leonora Piper was not the only one being scrutinized. The Fox sisters were also targeted and investigated along with hundreds of other mediums. The skeptics had arrived.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter three: disproving the paranormal. Proof: physical evidence, observable sensations, detectable noises. This was key to 19th century investigations of the supernatural.

Deborah Blum: If I just tell you that your great-aunt Sarah, you know, is… wants to say, you know, move that picture on the mantle, um, how do I know that’s her? I want some kind of physical proof of that.

Lisa Berry Drago: And it wasn’t only true believers who wanted signs, or skeptics who wanted something to dispute. Scientists also had skin in the game. If spiritualism was real, shouldn’t it be possible to get evidence of it?

Alexis Pedrick: In the 19th century, many scientists believed in both the supernatural and the scientific method. Henry Sabert, a prominent chemist from Philadelphia, was one of them. When he died in 1883, he left the University of Pennsylvania $60,000, a huge sum of money. But there were strings attached. Sabert was a big-time believer in spiritualism, and, like, William James, he believed it was worthy of deeper study. He wanted the University of Pennsylvania to use that money and put their biggest scientific brains to work, to investigate the most credible spiritualist claims, and prove them right.

Lisa Berry Drago: So, yes, true story, the University of Pennsylvania used to have a ghost hunting division.

Alexis Pedrick: Now, this ghost hunting division got right to work. Publicly, the commission presented itself as objective and open-minded, but privately, many of the people on the commission actually wanted to discredit spiritualists.

Lisa Berry Drago: One of its members was Howard Ferness, a University of Pennsylvania psychologist who described himself as, quote, “a viper, warmed by spiritual nonsense,” unquote. Ferness did not set out to prove the spiritualists right. He was set on debunking them.

Alexis Pedrick: And you have scientists who also recognized that people who, you know, are dedicated spiritualists, are very not trusting of science. Then- then there were all kinds of reasons for scientists to go after these people, and especially women like Maggie and Kate Fox, who were at, you know, sort of at the forefront of this, and driving some of these people who were now rejecting mainstream religion and rejection the principles of science, because they had evidence in front of them that these, they were started as girls, but let’s say, you know, continue as young women, can talk to the dead. So science is wrong, right? And that has to be countered.

Lisa Berry Drago: So Ferness took aim at one of the Fox sisters, Maggie, who was a middle-aged adult at this point.

Alexis Pedrick: Well, I mean, the Fox sisters were high-profile targets, and the standard approach of people is, a- and investigators, especially investigators who wanted to debunk something, were twofold. One is they would both investigate overtly, and they would investigate covertly. Right? They would plant people in the audience, they would plant people with fake stories, they would see how far they could sucker the mediums into, you know, these fake stories that weren’t true. It worked really well.

Lisa Berry Drago: When the commission met with Maggie Fox, there were faint thumps shaking the floor. Maggie said that the knocks came from Sabert himself. She was getting strong vibes that he wanted the commission to be thorough and patient. This was a pretty cool move, but it didn’t win her any fans in the move. The commissioners went on with their tests. They made her sit or stand on various surfaces to see if the noises persisted. They asked her questions over and over and over. At one point, to test if she was moving her body to make the taps, they even tied her up.

Alexis Pedrick: Yeah, we agree, this doesn’t sound very scientific, or very fun.

Deborah Blum: Lots of experiments of the 19th and early 20th century, you know, are not that sophisticated. I’m not letting these guys off the hook. There’s- there’s a form of torture to this. But you also have to look at the state of science at the time, and say, you know, “How do I test if this is a real trance or not?” Right? And I’m not sure if, and I don’t see this happening, people were investigating trace mediums today, how would they test that?

Lisa Berry Drago: The commission released a report saying that the Fox sisters were nothing but hoaxers. Spiritualists and psychical researchers spoke out against it, saying that the commission had acted in bad faith.

Alexis Pedrick: Sadly, the sisters’ story ends pretty tragically. Maggie Fox suffered from alcoholism, and later wrote a tell-all confession for the New York World magazine. In it, she explained that all along, the tapping sounds had actually been their toe joints loudly cracking. People in the spiritualist community called her a sellout, and she later recanted this confession, but it was too late. The Fox sisters were completely discredited, and they died penniless.

Lisa Berry Drago: By the time the Fox sisters died in the 1890s, the tide was turning against the spiritualist movement. More and more mediums began to be investigated. The more popular the medium, the bigger target they became.

Deborah Blum: There was a lot of public debunking of professional mediums, right? And there were a ton of people who had taken advantage of this interest who were, you know, frauds and fakers. And that became increasingly obvious. In the same way that there was a lot of early publicity about the wonders of the Fox sisters, there was a lot of publicity about, you know, these spectacular crashes and burns by other less-known, well-known mediums, but still pretty high-profile.

Lisa Berry Drago: The so-called scientific investigations into the Fox sisters and Leonora Piper point to the problem with investigating this phenomenon in the first place. How can you scientifically prove something that’s inherently unprovable? You can’t. And that’s one of the reasons why most scientists eventually gave up on investigating spiritualism.

Deborah Blum: The way that science works, science is not really structured in a way to measure paranormal experiences. How do you replicate? And I’ve used the example of this with what people today call near-death visitants. But at the time that your mother, I’m making this up, your mother in another country dies, right, you don’t know, but at the moment of her death, you feel a touch, hear her voice, see her out in the yard, people report. This is the most common of the paranormal experiences, actually. How would you replicate that? You can’t go back and have your mother die again, right? You weren’t hooked up to any monitors that registered any changes.

Lisa Berry Drago: What the psychical community was left with was a lot of gathered data, but no conclusions.

Deborah Blum: They had a incredible archive of experiences that could not be explained away entirely. But what they didn’t have was scientific proof. Hints and flickers and promises and frustrations, but not more than that. And 100 or so years later, uh, I’m not sure we’re past that. You know, going back to the 19th century, you start seeing, you know, this rise and then fall of the physical medium, because people wanted tangible proof. People wanted scientific proof. And the ghost hunters of today, the paranormal societies of today, you know, they’re still hoping to find that.

Lisa Berry Drago: Another reason why the sincere scientific investigation of spiritualism was because William James died. While he was alive, his reputation helped support psychical research as a serious scientific pursuit.

Deborah Blum: I do think the fact that he was, you know, such a famous psychologist and philosopher, and- and so involved in this, helped keep it, at least in the science community, it gave it, uh, at least something of a… of a near… of respectability, and- and kept scientists, at least, feeling like, you know, they could still look into this. So I think his death made a huge difference that way.

Lisa Berry Drago: James remained curious about spiritualism up until his death, and wrote about it until the end. He refused to either believe in it blindly or debunk it fully. He didn’t get the answers he sought, but he still found value in asking the questions.

Deborah Blum: When I started working on Ghost Hunters, you know, part of it was that I was super curious about William James, who I had always thought was boring. [laughs] Right? I was like, yeah, yeah, another pillar of scientific society in Victorian times, and who was… is just a completely complicated, fascinating human being. And I occasionally still end up quoting him to people. You know, there’s a point where he’s talking to another scientist, and he says to him, you know, you want everything to be like a, uh, Italian garden, all orderly and everything. Rows and trimmed hedges and sculpted trees and whatever. But nature is everywhere gothic. Complicated and tangled and often inexplicable. And I found that a very useful way to thinking about the world.

Lisa Berry Drago: Today’s ghost hunting shows are relegated to the realm of the silly or the quirky, but just like the Fox sisters and other 19th century spiritualism efforts, they do still address something fundamental about the human experience.

John Peters: The, uh, basic premise of these shows is, in a way, the same premise as William James, is to say, what if, to, uh, keep the, uh, what if open. And I think that James is a lot more rigorous and tragic about it, ’cause he- he realized that, you know, the- the what if is a gamble. And it’s possible that science could ultimately reduce everything in human experience to causal mechanisms. He realized that there was… there’s a real danger of this, and I think that these shows are much less tragic and much more circus-like. You know, it’s- it’s a kinda popular, um, entertainment, or, you know, magic show.

Alexis Pedrick: And looking for that what if can, of course, be taken to the extreme. I mean, we’re living through a time of conspiracy theories on steroids. But we’d argue that interpretation is not inherently bad. In fact, John Peters says that it’s the core of being human.

John Peters: But it seems to me that sometimes, the psychical researchers and paranormal psychologists are really hoping they can get beyond interpretation, and they’re really hoping that they can find transmission or contact or connection, or mind to mind replication. I mean, that’s kinda the Holy Grail, to try to find the ability to send a signal. And- and to me, just ethically, poetically, aesthetically, just this seems wrong-minded, ’cause it seems to underestimate the nature of the human condition, which is one of interpretation. And- and this is something to be happy about. It’s a blessed fact, or a handsome fact. That’s the Emerson way of putting it. It’s a handsome fact of human life that we get to interpret. That isn’t a fallen, awful thing. I mean, that is what makes us human.

Lisa Berry Drago: Thanks for listening to this episode of Distillations.

Alexis Pedrick: If you wanna hear more about the anthropological side of modern ghost-hunting, check out our bonus interview with Colin Dickey. It’ll be in your feed next week. Remember, Distillations is more than a podcast. It’s also a multimedia magazine.

Lisa Berry Drago: You can find our videos, stories, and every single podcast episode at distillations.org, and you’ll also find podcast transcripts and show notes.

Alexis Pedrick: You can follow the Science History Institute on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for news and updates about the podcast and everything else going on in our museum, library, and research center.

Lisa Berry Drago: This episode was produced by Mariel Carr and Rigo Hernandez.

Alexis Pedrick: And it was mixed by Jonathan Pfeffer.