In this episode of The Disappearing Spoon, host Sam Kean explains how anasognosia, a disorder that describes people who cannot comprehend that they’re sick, can help us understand how our brains protect our own self image.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Padmini Raghunath

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

On October 2nd, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson was found lying half-naked on the floor of the White House bathroom. He’d suffered a stroke on the toilet and crumpled in a heap.

Two red gashes had opened up on his nose and temple, where he’d struck some exposed plumbing after collapsing. A White House usher later saw Wilson laid out on a bed like a wax dummy—looking all but dead.

For the next few months servants had to prop Wilson in a wheelchair each morning and hand-feed him. He spent his days either zoning out in the garden or watching silent movies on a projector. Even when Wilson returned to work, he could barely function, and often broke down crying, to everyone’s embarrassment. A staffer later described him as “a broken, ruined old man.”

But there’s one person who really wasn’t bothered by all this. Wilson himself. Despite being weak and bound to a wheelchair and even partly paralyzed, Wilson seemed to oblivious to how sick he was. He actually started campaigning for a third presidential term in 1920, and got furious if anyone suggested he retired.

When Wilson lost the Democratic nomination for president that year, he was crushed, and he left the White House in tears in 1921. He still thought he was at his peak, both mentally and physically.

His health got no better over the next few years—and neither did his delusion. As late as January 1924, he sat down to write his, quote, “Third Inaugural Address”—confident that he still would win that year’s election. Right up until he died a month later, Wilson was convinced he was 100 percent healthy.

So, what was going on here? Was it just stubbornness? Perhaps—you don’t get to be president without being strong-willed. But to be that delusional? How is that possible?

In truth, Wilson was probably suffering from a bizarre neurological disorder called anosognosia. The name means “without knowledge of disease.” It describes people who, as strange as this sounds, cannot comprehend that they’re sick. It’s a complete lack of self-awareness.

But however strange it seems, there is a real, neurological basis for anosognosia, and people engage in something similar all the time in everyday situations. In fact, a mysterious little incident involving Facebook a few years ago proves that this bizarre mental state is far more common than you might think.

From the Science History Institute, this is Sam Kean and the Disappearing Spoon, a topsy-turvy, science-y, history podcast where footnotes become the real story.

Believe it or not, Woodrow Wilson was not even the most blatant case of anosognosia among 20th-century political bigwigs. That dubious honor belongs to former Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas.

In December 1974, the 76-year-old Douglas touched down in the Bahamas to celebrate the New Year. He was accompanied by his fourth wife.

Within hours of landing, Douglas had a stroke and collapsed. He was airlifted off the island, and arrived at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C. It became his home for the next several months. But even after endless rehab, he could not walk, and his left side remained paralyzed.

Yet Douglas refused to resign from the Supreme Court. Finally, in March 1975, he badgered one doctor into granting him an overnight pass to visit his wife. Instead of heading home, however, Douglas directed his driver toward his office. He began catching up on work that very night and never returned to the hospital.

Douglas had some good reasons not to resign. He was a fierce liberal, and he worried that Republican president Gerald Ford would, quote, “appoint some bastard” to take his place. But Douglas mostly refused to resign because, in his own mind, there was nothing wrong with him.

When reporters asked about his health, he told them that, far from having had a stroke, he’d simply tripped one day and gotten banged up. Never mind his slurred speech and wheelchair.

When reporters pushed back on this, he challenged them to hike the Appalachian Trail with him. In one interview, he swore he’d been playing football, and kicking forty-yard field goals with his paralyzed leg that very morning. Hell, he said, his doctor suggested he try out for the NFL.

Douglas’s performance away from reporters was even more pathetic. He slept through court hearings. He got facts mixed up on important cases. He began whispering to aides about assassins. Because of chronic incontinence, his secretary had to drench his wheelchair in Lysol. Soon, the other eight justices secretly agreed to postpone all 4–4 cases until the next term, and not let Douglas cast deciding votes.

Finally, in November 1975, the other justices forced Douglas to resign. But even then Douglas kept showing up at work, calling himself the “Tenth Justice” and attempting to cast more votes. There’s nothing wrong with me, he insisted. I’m 100 percent shipshape.

Douglas’s story may be extreme, but people with anosognosia tell similar whoppers all the time—usually quite cheerfully. If they have a paralyzed arm and you ask them to raise it, they’ll grin and claim it’s tired. Or they’ll say, Oh, I’ve never been ambidextrous.

They also vastly underestimate their own deficits. If you ask a normal person who’s paralyzed on one side to lift a tray of cocktail glasses, they’ll grab the tray in the middle with their one good arm. Make sense. Not people with anosognosia. They grab the tray at one end with their good arm, and fully expect their paralyzed arm to help. And when they inevitably flip the whole tray over, they make up more excuses.

There are even cases of people being stricken blind and denying that. Their brains fabricate a map of reality from memory and hearing and smell. As you can imagine, it’s not very good! But no matter how many times they bang their shins into furniture or nearly get creamed by oncoming cars, they’ll keep right on denying it. They claim they’re not blind, just a bit clumsy, haha.

So what’s going on inside their brains? Fundamentally, anosognosia arises from the brain’s inability to update its image of the body.

Body updates are fairly common. If you get a haircut, your brain will update what you look like, so you’re not startled in the mirror. The same thing happens if you get sunburned or have a pimple. It happens on deeper levels, too. If you injure yourself permanently, your brain normally incorporates that fact into its new image of the body.

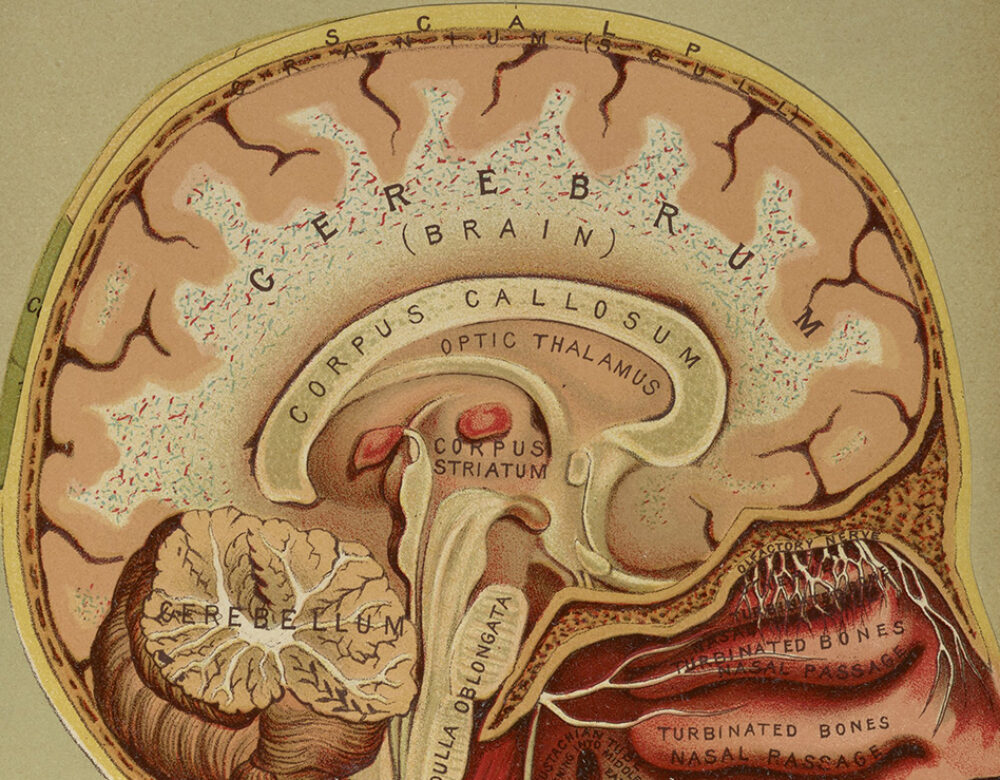

This mental updating is so common and so automatic that we don’t always realize how complicated it is. In reality, this process draws on several different areas of the brain. You have to take in new sensory information about what you look or feel like. You have to find the old sensations and memories and overwrite them. Those new memories then have to be retrieved successfully and pushed up into conscious thought so we’re aware of them. So again, it’s a multi-step process, involving multiple areas of the brain.

And damage to any one of those areas can cause anosognosia. Most commonly, people with anosognosia have damage to the parietal lobes, especially on the right side. The parietal lobes sit on the top of the brain, and they help integrate sensory information. Damage to the basal ganglia, thalamus, and temporoparietal junction can cause anosognosia as well.

Regardless of the specific location, the damage disrupts the brain’s ability to update its image of your body. As a result, the old image lingers. It’s like those sad people still living out their high-school glory days, convinced they’re still football stars and cheerleaders. Sometimes the delusions of anosognosia fade away and people accept their limitations. In other cases, the denial persists.

Now, I’ve been saying that people with anosognosia aren’t “aware” of their deficits. But really, that’s only half-true. They’re not consciously aware of their problems, no. But unconsciously, they often are.

We can see this in the metaphors that people with anosognosia use and the jokes they make. A doctor might ask them to raise their arm, and they can’t. They’ll deny that it’s paralyzed, but might concede that it’s “dead wood” or “rusty machinery.” While not fully truthful, those metaphors mirror the truth on some level.

Other evidence is even more striking. One neurologist asked a woman to rate her ability to catch an inflatable beach ball. Now, this woman could not lift her arm, much less perform athletic feats. She nevertheless rated her ability as eight out of ten.

Then the doctor got sly. He made the question less personal. He said, “If I were in your medical condition, how well could I catch the ball?” Suddenly, the woman’s rating dropped from eight out of ten to two out of ten. When she could distance herself, her answer was far more accurate.

Another trick to get at the truth involves joking around. If a doctor asks someone with anosognosia how well her paralyzed leg works, she’ll probably answer that it’s great. That she can kick field goals, or whatever.

But if the doctor smiles and gets a little goofy, things change. If he says, “Is your left leg ever naughty?”, she might start giggling. “Yes, it can be naughty sometimes,” she’ll say. “It won’t listen to directions!” By making the whole thing a joke or a game, the truth more or less comes out.

This is pretty staggering. Under most circumstances, these people are in complete denial—to the point of shattering cocktail glasses and wandering blind into traffic. But if you shift the questions just a little, to become less directly personal, suddenly they’re much more realistic and honest.

Why is this? Probably because, when things are less personal, people feel less threatened. Paralysis is scary—it can ruin your life. It’s easier to deny it, especially when, internally, you still feel like the old you.

In other words, beyond what’s happening neurologically, anosognosia might also be a protective measure. A self-defense mechanism for the ego.

Now, this might all seem extreme—something that only people with brain damage would do. And only when they’re facing something truly scary, like paralysis.

But self-protective measures like this are way more common than you might think. In fact, you yourself would probably engage in similar behavior, even in cases with much lower stakes. We can see this through people’s behavior on Facebook.

I first heard this story on Radiolab, although they didn’t connect it to neurology like I am going to do. In late 2011, Facebook was booming, with traffic numbers that most other websites never dreamed of. Remember Flickr.com? It was once the most popular photography site on the Internet. Well, in the single week between Christmas and New Year’s Eve in 2011, people posted more photos on Facebook than Flickr had ever had uploaded in its entire history. Just one week.

Inevitably, though, as the number of photographs skyrocketed, so did the number of complaints—cases where people objected to a picture as inappropriate.

Now, Facebook did have a button to report inappropriate pictures—nudity, drug use, hate speech, stuff like that. And Facebook employees had millions of flagged pictures to deal with that week in December 2011. Reviewing each case by hand would have required whole battalions of workers, several thousands. So they sat down and figured out how to automate the process.

They started by examining some of the flagged photos. To their confusion, they noticed that 97 percent of them weren’t actually offensive. In fact, the pictures had been blatantly mischaracterized. People were flagging puppies as hate speech, and ugly Christmas sweaters as crimes.

Facebook decided to dig deeper. Maybe people were just goofing around. But when they asked users, they denied it. They weren’t joking.

Instead, the people reported that the pictures had upset them. They looked drunk in the pictures, or fat, or had a bad hair day. Or maybe they’d recently broken up with someone and didn’t want to see their stupid face anymore. They’d flagged the images as hate speech or whatever simply because Facebook lacked the right category of complaint.

So Facebook gave people the right categories. Now whenever people flagged a picture, a box popped up that asked them how the picture made them feel. There were options like, “It makes me feel embarrassed.” And many people picked one of these options.

But there was also an option that said “other,” where people could write in whatever answer they wanted. And here’s where things got weird.

A full one-third of people chose the “other” option and wrote something in. And the most common complaint about a picture was, “It’s embarrassing.” Which … was odd. After all, Facebook had already given people the option to say the picture embarrassed them. And yet, people went through the extra work of clicking on “other” and then typing in “it’s embarrassing” instead.

That made Facebook curious. So, in a little experiment, they changed the default wording of the option from, “It makes me feel embarrassed,” to plain “It’s embarrassing.” Suddenly, the number of people picking that option skyrocketed, to almost 80 percent.

Why did this happen? Because of mental distancing. That little grammar tweak, of saying “it’s embarrassing” shifts the emotion from the realm of personal discomfort to this outside object. I’m fine—it’s the photo that’s problem. After all, it’s embarrassing.

Now, we can laugh about how silly this seems. But millions upon millions of people did this. It’s not rare. And notice that it’s exactly what the anosognosia patients were doing, too.

Remember, if doctors asked direct questions, people with paralyzed limbs felt uncomfortable and denied everything. But when doctors asked the questions in a less personal way, people were more honest. Similarly, as soon as Facebook made the objection less personal and less tied up with people’s pride and ego, they were more willing to admit the problem. It’s the exact same psychological defense.

And I think that’s a cool insight. I’ve written a whole book about neurological disorders called the Dueling Neurosurgeons. And most of the disorders in there seem exotic and strange. It’s easy to hear the story of Woodrow Wilson or William O. Douglas and think, That would never happen to me, only to people with brain damage.

But it can happen to you, in small but real ways. When our fragile egos are threatened, we’ll fib and quibble and deny like crazy. It’s sad but true. I’m even tempted to say that, for human beings at large, it’s a little embarrassing.