The 1800s had plenty of odd trends, but the height of strangeness might just be “mummy mania.” Prized as souvenirs, medicine, and even fodder for making paper, mummies in the 19th century were seen as tools for unlocking the secrets of ancient civilization. And this morbid practice was widespread, to the tune of 180,000 mummies being auctioned off a ship to passersby. But how did we end up with such a creepy and obviously outrageous trend? Why did people have such a disregard for ancestors and animals? And maybe most important, where were all the scientists?

Further Listening: Our sister podcast, Distillations, recently explored the historical roots and persistent legacies of racism in American science and medicine including how the study of human remains intersects with race. Check out 2023’s Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race season to learn more.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

People in the crowd were pretty skeptical. It was February 10th, 1890, in Liverpool, England. And there were rumors sweeping through town that a ship had just arrived from Egypt—full of mummies. There were even claims that the crew planned to auction the mummies off! It was preposterous.

But to people’s shock—the rumors turned out to be true. The crew started unloading sacks from the hold. And when a sailor reached inside one, he produced the mummy of a cat. And not just one mummy; there were thirty or forty cat mummies in the sack.

And there wasn’t just one sack. There were hundreds of them, perhaps thousands. That steamship arrived in Liverpool with 19½ tons of mummies onboard, some 180,000 of them. And just like the rumors promised, the crew proceeded to auction them off, like they were bags of potatoes or something.

So what the heck was happening? How could a ship just go to Egypt; pick up nearly 20 tons of mummies; then sell them to random blokes in England?

Well, it turns out that people had a different relationship to mummies back then. Mummies were not revered museum objects, or tools to unlock the mysteries of ancient civilizations. Mummies were souvenirs, or fodder for making paper. They were even eaten as medicine.

With Halloween approaching, now seemed the perfect time to talk about this topic. People have called different parts of the nineteenth century many things. The Gilded Age, the Victorian Era, the Belle Époque. But as much as anything else, the 1800s were a time of mummymania.

To understand how 19½ tons of cat mummies could end up in England, you have to understand the Egyptian relationship to mummies. Why did they make them? And what did mummies mean to them?

When most of us think of mummies, we think of a pharaoh in a tomb. The ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife, and mummification ensured that a person’s body would reach the afterlife in one piece.

To preserve a body, they essentially dehydrated it like beef jerky. People back then had no doubt come across accidental mummies before—the dried and shriveled remains of people who’d died crossing the desert.

Then, some clever soul figured out how to speed up that natural drying process. They used natron. Natron is a naturally occurring mineral in Egypt. It’s essentially a mix of baking soda and salt; it collects in dry riverbeds. It’s got an off-white color and forms a crusty powder.

The Egyptians would heap few hundred pounds of natron over a body for a month or two. The mineral would suck all the moisture right out. Without moisture, bacteria and maggots couldn’t putrefy the flesh. As a result, the body did not decay.

The Egyptians later developed all sorts of rituals to accompany mummification. They anointed bodies with sacred oils and resins. They smeared the skin with bitumen, a sticky tar. They also wrapped the bodies in linen. But all that was secondary in terms of preservation. As long as you dry a body out with natron, it’ll last almost indefinitely in the hot, dry desert.

So, that’s human mummies. But I don’t think a lot of people realize that ancient Egyptians mummified animals as well. A lot of animals.

They mummified baboons, hippos, fish, pigeons, rams, shrews, lions, beetles, lizards, owls, bats, hyenas, raptors, and more. Some of the cruder animal mummies look like sock puppets or piñatas. But the best embalmers would pose them in lifelike ways. Monkeys sat on their haunches. Cats curled their tails. Snakes were coiled to strike. Embalmers often painted faces on the wrappings, too.

Animals were mummified for many reasons. Some were beloved pets. Cats, dogs, horses, gazelles. It was the ancient equivalent of getting your pet taxidermied.

Other animal mummies were cuts of meat. These were placed in tombs for human mummies to snack on in the afterlife. Ribs, steaks, roast chickens. Some mummyfolk even got gizzards and other organs, perhaps for mummy gravy.

Still other animal mummies were sacred beasts. These beasts were worshiped by religious cults in temples. Examples included bulls and crocodiles.

The most commonly embalmed animals were so-called votive mummies. People bought them for devotional reasons, like votive candles today. The mummies were buried at temples or placed in underground catacombs as offerings to the gods.

The Egyptians produced votive mummies in staggering quantities. Archaeologists found one graveyard with four million bird mummies in it. Another graveyard had seven million dogs. Mummification was a high-volume industry.

Overall, mummies were sacred to ancient Egyptians. But after the fall of the last pharaohs, people in later centuries took a different view of them.

Tourism has been a big business in Egypt for thousands of years. The famous Greek historian Herodotus toured the pyramids in the 400s BC. By the 600s AD, Christian pilgrims were visiting sites from the Bible.

Many scholars also revered Egypt as a font of ancient wisdom. Especially medical wisdom. And mummies were tied up with this idea.

However, these scholars misunderstand the embalming process. As mentioned, the Egyptians dried bodies primarily with natron. Then they did secondary things like anoint them with resins, and smear them with bitumen-tar. But it’s the natron-drying that really preserved the body.

Unfortunately, later doctors didn’t understand that. They assumed that the resins and bitumen were doing the real work. And if those substances worked wonders on the pharaohs, perhaps they could help other people as well. In their minds, these substances had magical healing power.

From there, it was a short step to believing that the bandages and even skin of mummies also had healing power. After all, they too were soaked in those substances.

And gradually, by the logic of magic, people eventually came to believe that the mummies themselves had healing powers—the actual flesh and bone. So, they started grinding bits of mummies up and eating them, to ingest those powers.

You see similar logic in other cultures around the world. Warriors often assume that by eating the flesh of a dead enemy, they’ll absorb that person’s essence or power. We obviously don’t think like that nowadays, but there’s sort of an intuitive, poetic logic there.

The idea that mummies were powerful medicine began in Egypt and the Middle East. Later, the idea trickled into Europe after the Crusades in the 1100s. For whatever reason, Europeans believed that mummy medicine was best-suited to cure specific ailments. They thought mummies could heal cuts and bruises, and mend broken bones in just minutes.

Mummies were especially popular as a medicine between the 1400s and 1700s. Small bits of mummy were often ground into powder, mixed with liquid, and consumed as an elixir.

This medicine grew so popular that doctors often ran short on human mummies. At which point they substituted animal mummies—or even unlucky people who’d died in the desert long ago and shriveled up. Some crooked traders just smoked a camel over a fire and sold that as real, gen-u-ine mummy flesh.

Now, not everyone believed that mummies had amazing healing powers; some people were skeptical. But even famous thinkers like Robert Boyle and Francis Bacon hailed mummy medicine as a godsend.

Overall, by the end of the 1700s, you had tourists visiting Egypt, and people importing mummies with magical healing powers. So mummies were already pretty popular in Europe. Then Napoleon came along, and transformed that popularity into an absolute mummy frenzy.

In 1798, Napoleon and his army invaded Egypt. He did so for no other reason than he thought that conquering Egypt would make him look powerful and win him prestige.

Oddly, beyond all the troops, Napoleon also brought along a bunch of scholars—or savants, as they called them in France. Basically, these savants had their run of the country: total freedom to go wherever they wanted and take whatever art or cultural objects caught their eye. They were out for academic loot, the scholarly spoils of war.

The most famous bit of loot was the Rosetta Stone. This slab of rock had a kingly decree carved into it in both Greek and Egyptian hieroglyphs. It allowed savants to decipher Egyptian writing for the first time. I’ve actually recorded a bonus episode about the decipherment at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. It’s a fascinating tale of scientific detective work—as well as a juicy story of jealousy and nasty rivalries. All that and more at patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

Beyond the Rosetta Stone, Napoleon’s savants also looted art and other cultural objects—especially mummies. They started shipping them back to France in huge quantities. The sight of them in museums fired people’s imaginations.

In combination, the art and the mummies and the other cultural objects kicked off a fad that historians call Eygptomania. People in Europe adopted Egyptian-inspired clothing and jewelry. They decorated their homes with Egyptian objects. And Egyptomania wasn’t limited to France. England and Germany and Italy got swept up. People simply couldn’t get enough of Egypt.

One effect of the Egypt boom was to boost tourism to even higher levels. And the catacombs full of mummies were a big stop on most people’s itineraries.

Now, if you’re picturing a peaceful stroll through a cave, not quite. These were not easy places to visit. It was less of a walk, more spelunking.

People had to dodge bats and squeeze through 20-inch spaces wriggling on their bellies. Many people couldn’t breathe, for all the dust. Tourists even died in the catacombs. Some got lost and just never came out. Others suffocated in the stagnant air, or from the fumes of bat guano. They thereby added their own corpses to all the mummies in the catacombs.

But for many visitors, the risk was worth it. William Wilde, the father of Oscar Wilde, wrote eloquently about his experience in one tight catacomb:

“I contrived to scramble through a burrow of sand and sharp bits of pottery—frequently scraping my back against the roof … My guide [was] puffing and blowing like a porpoise, as he scratched out the passage, and groped through the sand like a rabbit for my admittance.”

But all Wilde’s troubles and frustrations melted away when they reached the sacred room piled high with thousands of animal mummies. As he said: “I do not think in all my travel [that] I ever felt the same strong sensation of being in an enchanted place.”

Eventually, a few enterprising merchants decided that, rather than bring the people the mummies, they could bring the mummies to the people. So they started shipping mummies to Europe. This wasn’t exactly legal, and there were often high export taxes on mummies. So Custom House officials cheated. They’d label shipments of mummies as “dried fish” or just “ballast.”

Sometimes these mummies were put to high-minded, educational purposes and ended up in museums. In other cases, scholars would unwrap mummies during public lectures to teach people about anatomy and ancient rituals.

But eventually, so many mummies began arriving in Europe that the market was glutted. As a result, people began using mummies in other, not-so-high-minded ways.

For instance, artists began grinding mummies up and sprinkling them in oil paints. A shade called “mummy brown” was especially popular.

Sadly, other industries just wantonly destroyed mummies. Like the paper industry. Back in the 1800s, paper wasn’t made with wood pulp like now. It was made with cotton and other fibers. Usually people got the fibers from rags.

But with mummies being dug up all over Egypt, paper-makers started buying them in bulk and pulping the bandages to make reams. You could get church hymns printed on a mummy. Newspapers used them as well. In 1855, New York state alone imported over 2 million pounds of mummy bandages for paper.

People used mummies as fertilizer, too. It was called mummy mulch. The bodies’ muscles were rich in nitrogen and the bones were chock full of phosphorus.

In fact, most of the cat mummies shipped to Liverpool in 1890 ended up as fertilizer. The cats were unearthed from a site 150 miles south of the pyramids. In ancient times, there was a temple there for an animal cult that worshiped a lioness. Hence the cats.

As mentioned, many of the mummies were auctioned off at the docks in town. People paid up to five shillings for the best ones, around $30 today.

But again, the steamship brought back 19½ tons of mummies, 180,000 of them. They couldn’t possibly sell all of them. Many weren’t worth buying anyway, because the ship’s greedy crew crammed too many of them into bags, and they got broken.

So, Liverpool farmers loaded them into donkey carts and hauled them off to their fields. Maybe they were hoping some of that mummy magic would help them grow peas and oats.

Mummies found their way into food via other routes as well. Gourmands in big cities reportedly cooked steaks over fires made of mummy; they swore that the burning bandages imparted a delicious flavor. There were tales of bakers grinding mummies into flour to make bread as well.

Unfortunately, even native Egyptians picked up the habit of destroying their mummies. Egypt doesn’t have many trees or much coal, so when the government started building the first railroads in the later 1800s, some conductors used mummies as fuel to fire their boilers.

Mark Twain actually tells a story about this. Apparently, when the trains were running slow and sluggish, the conductor would curse and yell. He’d claim the mummies of the plebians they were burning didn’t have enough punch. So he’d cry out, “Toss a damn pharaoh on there, that’ll get us moving.” Who knows if this was a Twain tall tale, but there was a nugget of truth to the practice.

Now, imagine what ancient Egyptians would have thought of all this. Their precious mummies—their sacred offerings to their gods!—were being ground up for paint, or used like manure. They would have been crushed or outraged.

And you might be wondering—where were the scientists during all this? Weren’t archaeologists hopping mad—furious at the abuse and destruction?

The answer is, not really. Most archaeologists back then cared only about grand structures like pyramids, and the mummies of kings and queens. The mummies of everyday people mattered very little to them. And they didn’t care about animal mummies at all. That was just the attitude back then.

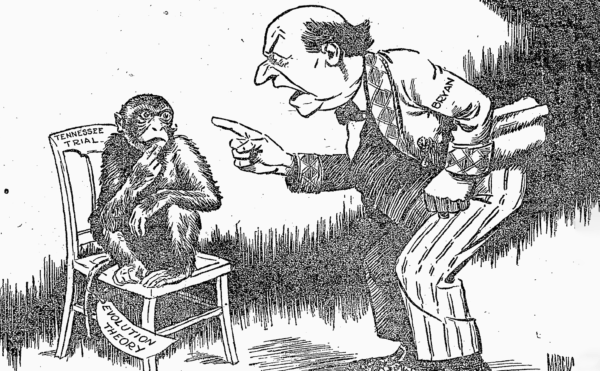

But one group of scientists did end up caring about mummies, and using them in their research. Theoretical biologists. Why? Because they were grappling with a radical new idea at the time—evolution.

As you’ll hear in part two of this episode next week, some biologists wanted to use ancient mummies as a test of whether evolution occurred at all. In fact, mummies were the very first test of evolution in history. And believe it or not, it’s a test that evolution would fail.