We normally think about syphilis as a venereal disease. But if left untreated, syphilis can invade nearly every tissue in the body, including the brain. In the early 20th century neurosyphilis accounted for fifteen percent of all insanity cases. It caused shaking seizures and paralysis, and every single person who caught it died horribly—until one doctor came up with an unorthodox remedy: intentionally infecting patients with malaria.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Music: “Delamine” by Blue Dot Sessions

All other music composed by Jonathan Pfeffer

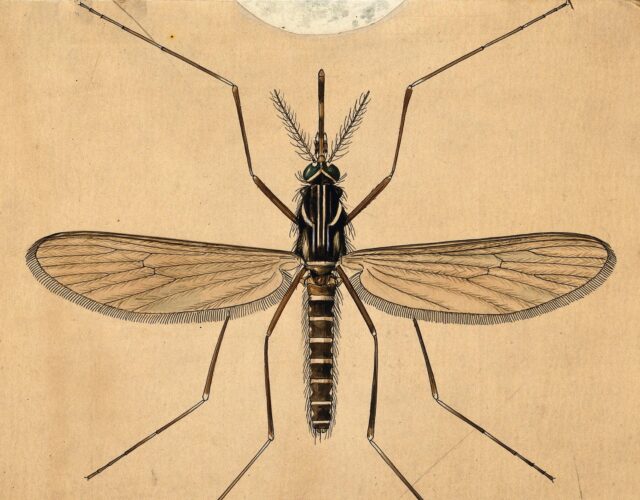

Image: Wellcome Collection

Transcript

No one who knew Dr. Julius Wagner-Jauregg ever called him kind. Aloof and distant was more like it. He had a gaunt, unsmiling face, with penetrating eyes and a handlebar mustache. If he’d been a cowboy, his nickname would have been Slim. As a young doctor in 1880, he got rejected for several jobs in general medicine in Vienna. So he reluctantly took a job in psychiatry—a total backwater at that time. In part because psych wards then were truly dismal places.

Without modern drugs, doctors had zero effective treatments for most maladies, and most patients spent every day in shrieking horror. One of the most disturbing problems was neurosyphilis—syphilis of the brain. We normally think about syphilis as a venereal disease. But if left untreated, syphilis can invade nearly every tissue in the body, including the brain.

And neurosyphilis was an especially cruel form of insanity. It caused shaking seizures and paralysis, and made people lose control of their bowels. Every single person who caught it died horribly—quaking with fear, babbling mad, and smeared with their own filth.

Overall, neurosyphilis accounted for 15 percent of all insanity cases. And doctors tried everything they could to cure it, including quack treatments.

<BURRRING> They drilled holes into people’s skulls. They applied flayed roosters and live frogs to the genitals. <RIBBIT> People chewed gum laced with mercury, or wore mercury-soaked underpants.

The wildest treatment involved sitting on a special toilet <CRACKLE> and lowering your genitals into the water for electric shocks. <ZAP> It didn’t work, but people were that desperate.

Even worse than the treatments was the social shame. Because syphilis was a venereal disease, syphilitics were often rejected by their own families. Even saying the word “syphilis” was considered obscene, and some doctors refused to treat people who had it.

So, this was the state of asylum care in Wagner-Jauregg’s day: insanity was incurable, and neurosyphilitics were the most reviled patients of all. But one day, he witnessed a miracle, something that made him question everything he knew and pushed him down a path that’s still causing controversy today.

It began with a psychotic woman that he treated in his ward in Vienna in 1883.

Or rather, did not treat. One day, randomly, this woman came down with a bad fever—intense and hot. She moaned for days, and barely pulled through. And when she woke up? Well, that’s the thing. She wasn’t crazy anymore. Her mental state had improved dramatically, without her doctors lifting a finger.

To Wagner-Jauregg the whole incident seemed spooky—yet also fascinating. Had the fever somehow cured her insanity? Did that even make sense?

He had to find out. He began scouring the medical literature, and he uncovered dozens of similar cases. An insane person would get a fever, survive it, and emerge sane. These were lost souls, barely human—and somehow a disease, of all things, saved them.

Wagner-Jauregg was baffled. What did it all mean? One thought in particular haunted him: All the cases he’d read about involved people catching fevers accidentally. But what if you gave someone a fever, on purpose? Would that also work?

It was a dangerous idea. Doctors cure diseases, they don’t induce them. And people died from infections all the time back then. Could he really risk infecting people?

Then again, as he looked around the ward at his howling mad patients, people utterly without hope, he asked himself another, more pressing question. Given their despair, how could he not risk it?

From the Science History Institute this is Sam Kean and the Disappearing Spoon—a topsy-turvy science-y history podcast. Where footnotes become the real story.

Wagner-Jauregg’s first experiments in treating insanity with fevers proceeded slowly, with great caution. He injected some insane people with the microbes that cause strep throat, and later tuberculosis microbes. But neither disease produced fevers reliably. Besides, patients often fought those ailments off. He needed something with prolonged fevers.

And unfortunately, he was too busy to give this work his full attention. By the end of the 1880s, he had family and was trying to establish himself professionally. He then became a professor and got distracted with administrative duties.

He kept trying different diseases in the 1890s and early 1900s. But before long his radical idea of curing insanity with fevers was just a half-forgotten pipedream. The audacious young striver had been replaced by a timid old man. And things might have stayed that way permanently, if not for World War One.

In 1917, a sixty-year-old Wagner-Jauregg was still working in a psych ward in Vienna. He later admitted he was in a bad state mentally. The slaughter of the trenches made life seem senseless. He was cynical and walled off, desensitized to the carnage. But one day in June 1917, something broke through.

On that day, a wounded soldier came in, a fellow with a mustache and a high forehead. The man had shell-shock. But that wasn’t all. He’d just returned from the trenches of Macedonia, near Greece, where he’d caught malaria.

Austria didn’t have malaria then, so Wagner-Jauregg wasn’t used to seeing cases. It’s a mosquito-borne disease, characterized by chills—as well as extreme fevers, well over 100 degrees. And as Wagner-Jauregg watched the mustached soldiers’ fevers come and go, come and go, something stirred inside him. Could malaria be the key to curing insanity?

The idea seemed crazy. If any disease was the work of the devil, it was malaria. It’s the single biggest killer in human history: more people have died of it than any other ailment. It’s not something to toy with.

But…what if? By 1917, there was a reliable treatment for malaria—the drug quinine, which I’ve mentioned on this podcast before. So Wagner-Jauregg reasoned that the risk was worth it. He could induce high fevers with malaria, but also stop the disease whenever he wanted with quinine. And however dangerous malaria was, it was better than the 100 percent death rate of neurosyphilis.

So one day, Wagner-Jauregg withdrew some blood from the mustached soldier’s biceps. Then, after a deep breath, he injected it into two patients with neurosyphilis.

And the moment he did so, he feared he’d made a terrible mistake.

You see, with most diseases, you can isolate people so the disease doesn’t spread. A quarantine. But malaria is spread by mosquitoes, which we cannot quarantine. So what if some mosquitoes bit his new malaria patients and escaped? The entire city of Vienna might erupt with an outbreak. Thousands could die.

The thought panicked him. He grabbed another asylum patient, a man who still had a few marbles left. He ordered this man to go to every room in the whole hospital and capture every flying insect he could.

So that’s how the patient spent the day. <BUZZING> He scoured every corner of the building—jumping, slapping, swiping, running, chasing those little bugs in endless circles. I mean, we’ve all tried hunting down lone bugs before—it can drive you crazy. But this man was half-crazy already, and he enjoyed it.

The patient then brought the pile of bugs to Wagner-Jauregg. He sat down with a trembling hand and scrutinized them one by one. At the end of which…he melted with relief. There were some mosquitoes there—but the wrong kind. They weren’t the type that spread malaria. The experiment could proceed.

Wagner-Jauregg ended up injecting nine patients with malaria that first round—a tram conductor, a clerical worker, an actor, a sergeant-major in the army. The first signs of malaria emerged three to eight days later—nausea and chills. Then the fevers started. They would spike as high as 106 degrees before breaking. After that, the chills and fever alternated every day, hot and cold, burn and shiver. Each patient suffered through seven rounds of this before Wagner-Jauregg cured them with quinine.

And the results…were stunning. Of those nine patients, six recovered. Three even returned to their jobs, fully cured. The other three did relapse, but only after months of coherence. And really, curing insanity even temporarily back then was a stunning achievement.

Over the next few years, Wagner-Jauregg expanded his experiments. Admittedly, several people did die of malaria at his hands. But he kept pushing, and after World War One ended, this so-called malariotherapy started to spread. First through Europe, then the Americas.

Its arrival in the United States was particularly noteworthy. The director of an asylum in Washington D.C. called up some colleagues in the tropics and ordered a dozen mosquitoes infected with malaria.

All but one mosquito died in transit. That’s because they got stuck to the tape holding the cages shut. So the last, precious, malaria-bearing bug was met at the airport by the military, and ferried across town in a ten-ton truck.

The truck outweighed the mosquito by ten billion times. But it was worth it. The mosquito proceeded to dine on, and infect, several different patients with neurosyphilis—and cured them of this once-incurable disease.

Overall, roughly 30 percent of neurosyphilitics recovered completely with malariotherapy. An additional 20 percent got partial relief.

As for why they got better, their high fevers almost certainly helped. Microbes cause neurosyphilis, and microbes die at high temperatures. That’s why our bodies generate fevers in the first place, to fight infections.

By that logic, however, hot baths should have worked just as well as malaria. But, they don’t. Doctors tried hot baths on insane folks, repeatedly, in the 1920s. And every time, external heat failed to cure neurosyphilis. Only internal fevers worked.

Today, scientists speculate that, while heat played a role in malariotherapy, the body’s natural defenses also helped. Perhaps malaria kicked the immune system into high gear, and it started attacking syphilis germs that went undetected before. But really, even today, no one knows why malariotherapy worked.

That lack of understanding always made scientists uneasy. And it didn’t help that malariotherapy outraged many people morally. Again, catching syphilis was considered shameful, and the ravages of the disease were considered god’s punishment. Malariotherapy was therefore ungodly, preventing people from reaping the just rewards for their sins.

More materially, some doctors objected to malariotherapy because they had sworn the Hippocratic Oath to do no harm. And however you slice it, giving someone malaria was pretty harmful. Because while malariotherapy did cure thousands, it also killed 15 percent of patients—an astronomical rate. Plus, what about the risk of malaria outbreaks in cities? Wagner-Jauregg had lucked out in there not being the right type of mosquito in Vienna. What if other cities weren’t so lucky?

For these reasons, some doctors considered Wagner-Jauregg not a savior but a villain. In fact, while some insisted he should win the Nobel Prize, others called him a devil.

Overall, though, the pluses outweighed the minuses, and in 1927, Wagner-Jauregg won the Nobel Prize. A full fifty-four years after he’d first considered using fevers to fight insanity, he’d reached the pinnacle of scientific medicine.

After this success, doctors tried the malaria cure on other diseases: polio, epilepsy, cancer, other types of insanity. It failed every time. Only neurosyphilis was vulnerable. And by the 1950s, when penicillin became widely available to treat syphilis, malariotherapy was just too risky to continue.

As a result of all this, Julius Wagner-Jauregg has disappeared from history. And some people today still condemn him as a monster. At best, there’s an “embarrassed silence” nowadays—a syphilis-level shame among doctors that they ever had to rely on something so crude.

But really, why the shame? Malariotherapy seems drastic only because we have the privilege of forgetting how bad neurosyphilis was. We’d probably make much different choices without modern psychiatric drugs. And lest we get too smug, malaria is bad, certainly, but doctors today induce no less misery with harsh chemotherapy drugs. Judge not, lest ye be judged.

They say that politics makes strange bedfellows. But nowhere was there ever stranger bedfellows than syphilis and malaria. Both were ancient scourges, among the most evil and devastating diseases in history. Yet, one cured the other. Syphilis has always had a moral dimension to it. But in this case, salvation came from the very work of the devil.

This is the Disappearing Spoon podcast, brought to you by the Science History Institute. Find out more about their library, museum, and multimedia magazine at sciencehistory.org.

Make sure you check out the Science History Institute’s other awesome podcast, Distillations. You can find their in-depth narrative stories and interviews about everything from Space Junk to Sex, Drugs, and Migraines anywhere you get your podcasts, and on their website: Distillations.org.

You can find more incredible stories from my books at samkean.com. You can also book me as a speaker at your school or event.

If you like this podcast, please support it at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. It costs as little as seven cents per day. You can also get bonus episodes and signed books.

Please spread the word to others as well, and subscribe in iTunes, Stitcher, or other places.

This episode was written by me–Sam Kean. It was mixed by Jonathan Pfeffer, and produced by Mariel Carr and Rigoberto Hernandez.

Thanks for listening…