After a health crisis, a Brazilian man suffered brain damage and began to give compulsively. His friends and family begged him to stop, but he couldn’t. His case, along with a handful of others, sheds lights on how the brain’s biology may promote giving, at least up to a certain point.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineering: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

In 1990, a quiet Brazilian man named João suffered a serious health crisis. He was only 49 years old. But he pulled through the crisis, and afterward, he told people he wanted to live differently. “I saw death from up close,” he said. “Now I want to be in high spirits.”

So João quit his job in human resources at an insurance company in Rio de Janeiro, instead began selling French fries from a street cart.

The fries quickly proved popular in his neighborhood. They were delicious—thin and crisp and golden. Even more enticing, João often gave them away for free. All you had to do was ask, and he’d scoop up a box of them, no charge.

And what money João did make, he often gave away to children begging in the street. Or he would use his profits to buy them candy. Day after day he came home without a single coin or Brazilian real in his pocket. But he couldn’t have been happier. Indeed, nothing made him happier than giving—whether from his savings or that day’s French-fry money.

João’s story might have been nothing more than fodder for Chicken Noodle Soup for the Soul. Except for one thing. That the “health crisis” that changed his life, was actually a stroke that left him with severe brain damage.

Among other symptoms, João stopped sleeping and lost his sex drive. He started forgetting things and had trouble focusing. His movements slowed down. And in the strangest symptom of all, he became “pathologically generous.” Compulsively driven to give.

The history of neuroscience is filled with patients like João whose behavior changed dramatically after brain damage. In some cases people suddenly became compulsive liars, or lost the ability to recognize faces.

But these strange and sometimes tragic cases also handed neuroscientists an incredible opportunity. By studying how people’s behaviors changed after injuries, they could determine what those injured parts of the brain did.

In a similar way, neuroscientists believe that the pathological generosity of João and other patients can shed light on normal generosity—helping us understand why human beings give, and why, biologically, giving feels so good.

João was a chubby man with pointy ears, soft brown eyes, peppery hair, and arched black eyebrows. Before his stroke, while working at the insurance company, he’d been stern and serious, prone to squirreling money away. But afterward, he gave, gave, gave without any thought of the consequences. To those who didn’t know him, he seemed like a saint.

But those who did know him felt differently. João didn’t own the French fry cart by himself. His brother-in-law owned half, and was alarmed to see all his profits disappearing. The two got into big fights about this. But the brother-in-law’s tongue-lashings never shook João’s resolve to give.

In fact, João eventually gave away so many fries that the cart went bankrupt. His giving nearly bankrupted his family as well. His son and wife had to borrow money just to live and almost lost their home. Even then João couldn’t stop.

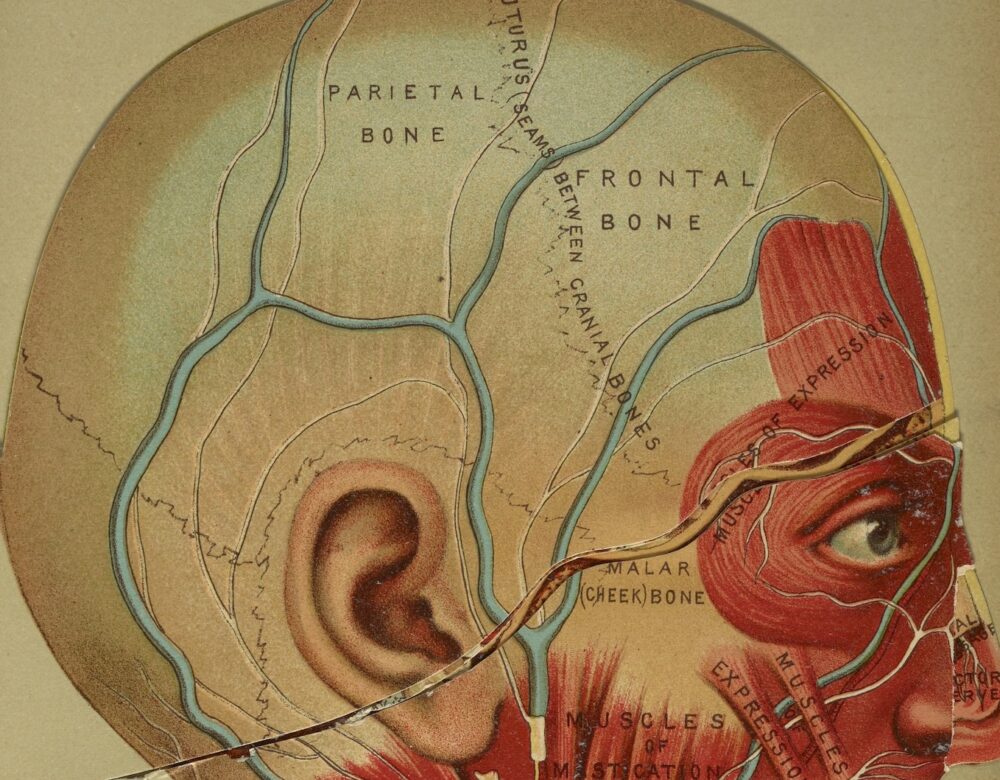

João’s stroke damaged a structure called the left medial forebrain bundle. It’s a collection of nerve fibers near the brain’s south pole. But understanding why that was so disruptive requires a bit of additional knowledge about the brain.

The brain’s frontal lobes monitor activity in other parts of the brain. This includes suppressing impulses and urges, especially in the service of a larger goal. For instance, it’s your frontal lobes that tell you that eating a third slice of chocolate cake will probably give you a stomach ache.

Now, João’s frontal lobes suffered little damage during the stroke. But to monitor other areas, the frontal lobes need to receive input from them. And that’s where the medial forebrain bundle comes in.

Like an internet line, this bundle pipes in data from all over the brain. And when the stroke destroyed that bundle, his frontal lobes lost the ability to monitor and suppress impulses in other brain regions. Including an impulse to give money away.

Whenever street children approached him and asked for money, João could not help but reach for his wallet. It was more or less an automatic reflex—like Pavlov’s dogs salivating when they heard the dinner bell.

The stroke also seemingly disabled the brain’s “punishing mechanisms.” That’s the system that chastises dumb behavior. In most of us, this system would have stepped in and said, You idiot. You’ll lose your house if you keep giving money away.

But when the punishing mechanism gets damaged, that self-scolding never takes place. No matter how low João’s bank account ran; no matter how many times his family yelled at him, his behavior didn’t change..

Now, not all pathologically generous people have suffered strokes. Other ailments can produce the same symptoms. So can tweaking brain chemistry.

One important chemical in the brain is dopamine, a neurotransmitter. Dopamine plays a role in the brain’s reward and pleasure circuits. Special cells produce dopamine, and the death of those dopamine-producing cells is actually what causes Parkinson’s disease.

Certain drugs out there fight Parkinson’s by trying to restore dopamine levels to normal. Unfortunately, those drugs are pretty crude. And they often produce strange side effects—like an overwhelming urge to gamble. Those affected seem especially drawn to the bright lights and repetitive motions of slot machines.

In addition to gambling, other cases of compulsive behavior have emerged, too. One man was diagnosed with Parkinson’s at age twenty-three and began taking dopamine drugs. Afterward, he started lifting weights and shopping compulsively; he once bought sixty bottles of aftershave in one trip to the store. He also exhibited pathological generosity. He gave away so much money from his disability checks that his electricity got cut off.

Another case involved a forty-nine-year-old British naturalist with Parkinson’s. After he started taking dopamine pills, he began writing obsessively about mushrooms and toadstools—sometimes for forty-eight hours straight. He also began handing out sandwiches and money to homeless people that he met on walks around town. He gave one young woman £20,000 in loans and gifts, money his family could not afford.

Like João, neither of those two had been particularly generous before starting the drug. But somehow dopamine—just a few carbon rings studded with nitrogen and sulfur—transformed these people into super-givers. How?

Overall, what pathologically generous people feel seems to be an exaggerated version of what we all feel when we give. Like when we donate a sack of groceries at Thanksgiving or hand out money on the street. It’s a feeling different in degree, but not in kind.

You can see this on brain scans. In 2006, a neuroscientist at Northwestern University recruited nineteen volunteers with typical brains. Each one had to lie down in an fMRI machine and decide whether to donate money to certain charities. The scientists monitored which brain systems were most active during this task.

As expected, the scientists saw heightened activity in the people’s frontal lobes. That’s because the frontal lobes help us weigh different courses of action and decide what to do. When it comes to charity, the frontal lobes help determine when to give, who to give to, and how much.

But other areas besides the frontal lobes also got busy on the fMRI scans. The scientists were in fact startled to see the brain’s pleasure and reward circuits light up as well.

The pleasure and reward circuits are ancient pathways in the brain. Neuroscientists usually associate activity in them with hedonistic pleasures like food and sex. But giving away money also excited this circuit. In fact, giving away money revved it up more than receiving money did.

Overall, then, what your mother might have told you is true. Tis better to give than to receive. Neurobiologically, it’s roughly on par with eating fudge or getting laid. And this ecstatic pleasure was exactly what the pathologically generous people felt.

So if the rest of us started gobbling dopamine drugs, would we become pathologically generous? Probably not. At least some brain damage seems necessary first.

But again, that brain damage can take different forms. Strokes. Cell death. Even abuse.

One psychotherapist reported a case of pathological generosity in an elderly woman who’d been sexually abused as a child. Such abuse can alter how brain circuits work in deep and lasting ways. She offered the therapist a cool million dollars for therapy sessions, which he refused. She also flew a young boy that she met randomly at a mall to a theme park in a private jet for $30,000. Just because.

In the case of Parkinson’s disease, the damage is more obvious: when the dopamine-producing cells die, the brain’s pleasure and reward circuits fizzle out or stop working. As a result, in these people, the joys of life no longer thrill them. Art, music, food, friendships—they all seem blah.

However, when they take the dopamine drugs, the reward circuits start revving again. The joys of life return, and they crave the pleasure. And because acts of generosity can tap into the brain’s reward circuits, some people start giving and giving and giving to keep the high going.

Scientists already know that drugs like cocaine and amphetamines can cause a spike in dopamine levels, among other effects. That’s a big reason people abuse those drugs, to keep chasing that dopamine dragon. In a similar sense, pathological givers might be addicted to philanthropy.

The internal glow people get from giving is just part of the story. Generosity also affects people’s relationship with those who receive the gifts. And over the long term, this social aspect of giving had profound consequences for our species.

Unfortunately, pathological giving tends to put people off. Sometimes givers press dozens or even hundreds of gifts on friends or family members, who can find the crush of presents bewildering and embarrassing. And those who give compulsively to strangers often anger their loved ones, especially when the giving destroys their finances. Some families refuse to let the pathological giver out of the house unsupervised.

This contrasts sharply with normal giving, which tends to bring people together. The recipient enjoys the gift, and wants to reciprocate in the future. As for the giver, MRI studies show that givers have heightened activity in the brain’s subgenual area. This region controls the release of oxytocin. This neurotransmitter promotes social bonding. Concentrations of oxytocin swell whenever we gaze at our children or loved ones.

These social rewards of giving could help explain why generosity took root in the human brain in the first place.

Explaining generosity—or more generally, explaining altruism—is actually a headache for biologists. Charles Darwin considered it one of the gravest threats to his theory of natural selection.

To see why, imagine a tribe of our ancestors whose members varied in their generosity. Some people were giving souls, willing to share food and goods. Others were stingy and refused. Frankly, the generous ones sound like better people, but from a survival standpoint, they’re taking a big risk.

With only so much food to go around, anything they shared with others meant less food for themselves and their children, especially in times of hardship. Overall, the math is clear and cruel: within a few generations, selfish people outcompete generous people.

But there’s a loophole here. In the mid-1900s biologists began explaining acts of altruism through something called kin selection. It turns out that animals are more likely to be generous and altruistic toward relatives, with whom they share genes.

In other words, kin selection explains altruism as disguised selfishness. I might sacrifice myself in the short term, but helping my siblings survive will ultimately boost the chances of my genes carrying on in the future. Kin selection has since become a cornerstone of modern biology.

But however suited for animals, kin selection seems unsatisfactory for human beings. It’s not that humans are somehow above the evolutionary pressures that shape other species. We’re not. And kin selection does take place among humans.

But humans also help out strangers all the time, every day, across the world. So on the one hand, altruistic generosity seems impossible, since generous people are destined to lose the evolutionary arms race to selfish people. On the other hand, anyone with two eyes can see that human beings are generous creatures.

But the neuroscience of giving could help explain how traits like generosity got a foothold in our brains. Again, giving feels good on a basic neurological level, so we like to do it. And, crucially, giving brings people together and encourages reciprocity. That helps stabilize relationships and promote trust. Those bonds in turn help people weather hardships. Building up trust over time, even among non-relatives, has a survival advantage.

In other words, human society depends on the very same social bonds that generosity forges in the brain. And that’s why scientists study cases like João and the Parkinson’s givers. By ramping things up to extreme levels, those cases help us see exactly how generosity works in the brain—including where it succeeds in establishing social bonds and where it fails.

As of right now, scientists don’t know why two people can have identical lesions or take identical doses of drugs, yet only one of them starts giving their life savings away. Something about the person’s psychology or background might play a role.

Scientists also don’t know whether injuries or drugs create an instinct for excessive giving that wasn’t inside people before, or whether injuries or drugs simply unmask an instinct that was suppressed before.

The neuroscience of giving raises some uncomfortable questions, too. We normally think about generosity as pure and noble. It’s supposed to be evidence of the best of humankind, not evidence of brain damage.

But while generosity does engage our “higher” brain regions, it also strums our greedy pleasure circuits, circuits normally associated with food, sex, and drugs. Overall, then, the urge to give arises from a blend of refined charity and base appetites.

We can see all these forces at work with João and his French fry cart. Sadly, nearly a decade after his stroke, João died in 1999, of kidney failure. But he died happy, based on years of giving. In fact, his neurologist said that João was the happiest person he had ever met.

At the same time, João’s fights with his family forced his neurologist to think about the dark side of generosity. As his neurologist said, “João’s case … reminds us that the borderlands between good and evil may be more subtle than is ordinarily assumed.”