In this episode of The Disappearing Spoon, Sam Kean shares how a close examination of barnacles—not finches, or any of the Galápagos’s other exotic creatures—provided Charles Darwin with the missing link to his theory of evolution.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Padmini Raghunath

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffe

Transcript

If you had to pick one animal that influenced Charles Darwin, what would it be? Most people would immediately pick the famous Galápagos finches. Or perhaps the islands’ lumbering tortoises. The finches especially have become iconic—their precisely crafted beaks, each one tuned to a different ecological niche.

But the truth is, Darwin didn’t really care about finches. He did collect some on the voyage of the Beagle, but made a complete hash of them. He actually misidentified them, calling them grosbeaks [“gross-beaks”], and had to be corrected by an expert back in England.

Worse, he forgot to record the island of origin for most of the finches, making them useless for evolutionary study. Darwin didn’t even mention the finches in On the Origin of Species. As for the Galápagos tortoises he collected, well, Darwin ate them on the voyage home.

So while pop culture associates evolution with the Galápagos, Darwin left the islands in the same state he’d arrived—a committed creationist.

So what animals did shape his theory of evolution? Pigeons, for one, and worms. But the biggest influence on Darwin was a lowly, much-despised marine pest—none other than the barnacle.

From the Science History Institute this is Sam Kean and the Disappearing Spoon—a topsy-turvy science-y history podcast. Where footnotes become the real story.

The start of 1835 found Darwin miserable. He was three years into the Beagle voyage, and had been wretchedly seasick for much of the trip, unable to eat anything but raisins for many meals. So when the Beagle anchored off Chile in January 1835, Darwin scrambled ashore to walk the beach.

After his cramped quarters on the ship, the open sky must have felt dizzying. A lush green canopy hovered over the silky sand, with snow-peaked mountains in the distance. Wild potatoes grew near shore, and otters splashed in the water, hunting crabs.

Among other specimens on the beach, Darwin collected a strange shell. It was coconut-sized and sand-colored. It also had one baffling feature: hundreds of millimeter-sized holes, as if somebody had blasted it with tiny buckshot. He’d never seen anything like it.

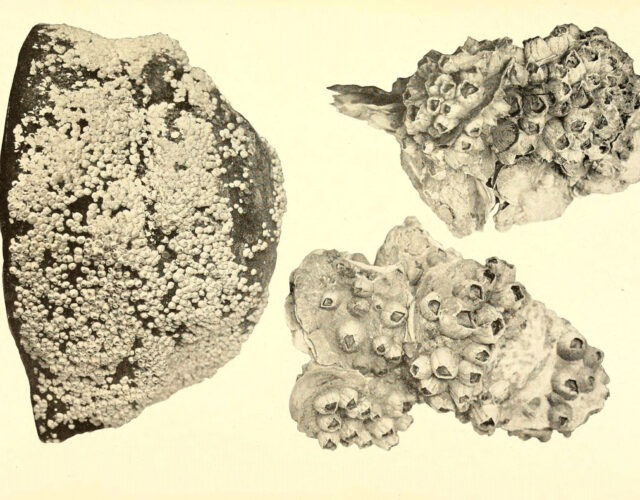

That night, in the Beagle, Darwin pulled out his microscope to study the holes. Using a needle, he found something unexpected inside them—minute barnacles, a tenth of an inch long. They were cream-colored and curled like hairpins.

Unlike other barnacles, these ones lacked shells. Also, most barnacles secrete a cement-like glue and lock themselves on to anything convenient—ships, docks, even the bellies of whales. But these barnacles were living as parasites inside another creature’s shell. No scientist had ever seen anything like it.

Now, much more happened to Darwin on the Beagle voyage. But amid all the wonders he saw—leaping frogs, chattering monkeys, explosively colored birds—his mind kept circling back to that funny species of barnacle. He nicknamed it Mr. Arthrobalanus, which means “jointed barnacle.” And when he returned to England in 1836, he was eager to study Mr. Arthrobalanus more thoroughly.

Alas, life intervened. As the Beagle’s naturalist, Darwin had official reports to write. A general travelogue appeared in 1839. Then a book on coral reefs in 1842. However well received, these were hardly major advances.

Meanwhile, Darwin happened to read a gloomy essay by preacher Thomas Malthus on starvation and the struggle for survival. Gradually, this kindled an idea in Darwin. If life was a struggle, then beneficial traits would give some creatures an advantage. As a result, they’d have more offspring. It was the first glimpse of his now-famous theory of natural selection.

Still, at that point, it was just a theory—hardly proof. And to his frustration, Darwin recognized a big flaw in this theory. Uniformity.

Darwin had collected thousands of animals from across the globe, and he of course could see differences between different species. But within a species, all the individuals looked pretty much the same, even to his naturalist’s eye. Barnacle A and barnacle B and barnacle C were all uniform.

But natural selection needs variation to work on. If barnacle A and B and C were identical, natural selection wouldn’t work. To his frustration, Darwin realized that uniformity could prove a fatal flaw to his theory.

However puzzled, Darwin wrote up a summary of his theory in 1842—along with instructions to publish it if he died suddenly. Then it was back to the Beagle grind. Darwin soon published books on volcanos, then the geology of South America.

Throughout this time, Darwin was spreading himself too thin. He wasn’t hunkering down and focusing on his Big Idea of natural selection. Some historians have called Darwin during this time a “genuine dilettante.”

And it wasn’t just historians. In a letter to the botanist Joseph Hooker in the early 1840s, Darwin began babbling at one point about his theory of evolution and the origin of species. In a reply, Hooker sharply rebuked him. How can you claim to know the origin of all species, Hooker asked, if you’ve never sat down and studied even one species in detail yourself?

Darwin was mortified. He’d basically been called an amateur, a dabbler. He had to fix this.

And that’s when he remembered Mr. Arthrobalanus. He decided to spend a month studying this barnacle, to prove to Hooker that he could describe species in detail. Then he could jump back into his big theory about evolution and shore it up. Easy peasy.

Darwin had no idea that, instead of a month, barnacles would dominate his life for the next eight years.

The problem was this. Darwin wanted to describe Mr. Arthrobalanus. But how was he supposed to know what made Mr. Arthrobalanus unique without comparing it to other barnacles? So he began writing letters to museums, requesting barnacle specimens to study.

Unfortunately, Darwin quickly realized that all existing work on barnacles was sloppy and third-rate. There were huge mistakes everywhere. With a sigh, Darwin realized he would have to reclassify everything himself. He started writing more letters, requesting more specimens.

Smelly boxes began arriving at his home from all over the world. He kept them in teetering piles in his study.

Peering through a microscope, he used pins and porcupine quills to dissect the barnacles and tease apart their wispy organs. Whenever he saw something interesting, he’d push his wheeled stool back and scribble down a note in his atrocious handwriting.

He often worked straight through the night beneath an oil lamp—straining so hard that he suffered migraines and intestinal distress, even nightmares. Doctors begged him to stop—his health was nearly broken.

Darwin refused. Every day the postman rang, and every day the piles of barnacles grew treacherously taller.

Word about Darwin’s mania soon got around. A popular novelist made fun of him in a book, satirizing him as a pedantic bore whose lectures on marine critters put everyone to sleep.

Then there was the story about Darwin’s son George. As a boy, George visited a friend’s house, and was flabbergasted to learn that the friend’s father had no dissecting desk and no microscope. George stammered, “But, then where does he do his barnacles?”

But however much people mocked him, Darwin’s barnacles were providing fascinating insights into evolution.

For one thing, he noticed how certain organs in one barnacle species were often repurposed in another species. It’s similar to how the forelimbs in ancient mammals got transformed into wings in bats and flippers in dolphins.

Conversely, he discovered that unused organs often withered away, especially when it came to barnacle sex.

Now, barnacle sex is a fascinating topic. I’m not kidding. Given that barnacles are stationary, they need incredibly long penises to do the deed. Penises eight times their body length, the longest penises in nature. Sex organs can also grow in different shapes, depending on whether they live in rough or calm water.

But the real eye-opener for Darwin involved Mr. Arthrobalanus. All known barnacles then were actually hermaphrodites, with both male and female sex organs. So in calling him “mister,” Darwin was mostly joking around.

But in truth, the joke was on Darwin. It turned out that Mr. Arthrobalanus’s species was not hermaphroditic. In fact, Mr. Arthrobalanus wasn’t a mister—he was Miss Arthrobalanus, a female.

So where were the males? Embarrassingly, Darwin nearly threw them away. He’d been finding little tick-like things attached to Miss Arthrobalanus. He assumed they were parasites and picked them off. In reality, these tiny “ticks” were the menfolk.

The men were ten times smaller than the females, and consisted of nothing but sacs of sperm. All other organs, like stomachs and heads, had been whittled away by evolution. Each female routinely kept two or more “husbands” around to service her, a fact that Darwin chuckled over.

But this arrangement also got him thinking. Darwin soon found another barnacle species with no females. In that species, half the individuals were hermaphrodites and half were dwarf males. That is, males on their way to becoming nothing but sperm-filled ticks.

In other words, he’d found a transitional state between hermaphrodites and distinctly sexed barnacles. A missing link. The discovery electrified him: “Down among his barnacles,” one biographer wrote, “he felt he was seeing evolution in action.”

Even better things were coming. Remember, Darwin’s initial, groping theory of evolution still had a big flaw. Uniformity. If all creatures within a species looked identical, how would natural selection determine who lived and who died?

It was here that Darwin’s obsessive focus on barnacles really paid off, with the biggest insight of his life.

To understand that insight, we’ll need to take a quick detour into, of all things, the human face.

It’s hard to overestimate how good we humans are at recognizing faces. All faces consist of the same exact parts in the exact same configuration—eyes, nose, lips. And aside from a few outliers with big schnozzes or whatever, there are millimeter-scale differences among those parts.

Yet most humans effortlessly recognize thousands of people a glance—and can do so from multiple angles, in all sorts of lighting. Beards or heavy makeup hardly slow us down. We can even match people to childhood photos in a snap.

We rarely think about this ability, because it’s so automatic. But our facial-recognition skills are no less amazing than a bloodhound tracking odors or bats using sonar. It’s a human superpower.

We can see this superpower reflected in our brains. When people view faces, neuroscientists can detect a characteristic spike of electrical activity inside the skull. This spike is centered in a region behind and above your right ear, the so-called fusiform face area. It’s a special brain circuit just for processing faces.

Faces are neurologically special in other ways, too. Consider the inversion effect.

If you flip a picture of a face upside-down, it’s suddenly much harder to recognize it or remember it later. Dozens of studies confirm this: we’re slower, less accurate, and have worse memories with inverted faces.

Now, this does not happen with objects. If you flip a picture of an airplane or a flower upside-down, people struggle a little. But with objects, the drop-off in performance is always, always minuscule compared to the drop-off with faces.

At least that’s what scientists thought. In the 1980s, two neuroscientists at MIT published a startling paper on dog-show judges and dog handlers. These men and women had spent thousands of hours studying and critiquing canines.

So the neuroscientists flashed pictures of certain dog breeds at them. Setters, terriers, poodles. And when viewing upright pictures, the judges could effortlessly recall individual dogs later.

But when the neuroscientists flipped the dog pictures upside-down, suddenly the judges stumbled. They struggled to recognize them. A clear inversion effect.

Importantly, this did not happen with novices, people who were not dog experts. Novices recalled dogs equally well both right-side-up and upside-down. Only the experts struggled. Their brains were treating dogs like faces.

Since then, dozens of studies have reached similar conclusions. When experts see things within their domain of expertise, their brains treat those things like faces. Specifically, their brains produce a spike of electricity in the fusiform face area; and they fall victim to the inversion effect and other deficits. This happens to birders with birds, chess masters with chess boards, radiologists with x-rays, car aficionados with cars, graphologists with handwriting samples, and on and on.

Essentially, after years of study, the brains of experts “recruit” the fusiform face area and extend its superpower to other domains. Their brains magnify the millimeter-scale differences among dogs or birds or x-rays into blatantly obvious ones. They can tell those things apart as easily as most of us distinguish faces.

So where does Charles Darwin fit in? Remember, when Darwin the dabbler began, all individual barnacles within a species looked the same to him. He could not tell them apart. But box by box, barnacle by barnacle, he turned himself into an expert.

As a result, he started noticing variations he never saw before. One barnacle might have a thinner shell. Another a wider mouth. Yet another longer legs or oddly shaped organs. As Darwin once said, he marveled over, quote, “the variability of every part … of every species.”

Now, of course we don’t have neurological scans of Darwin. But based on what we know with dog-show judges and other experts, it’s likely that his brain recruited his fusiform face area and rewired his neurons to parse barnacles.

And here’s the payoff—the key insight into Darwin’s theory. Most people associate Darwin with evolution, but that’s not quite right. People had actually been discussing evolution long before Darwin.

In fact Darwin’s own grandfather, Erasmus, once published a long, rambling poem about evolution and the descent of all creatures from a single ancestor. And he did so in 1802—seven years before Darwin was born. The idea of evolution was already in the air.

Darwin’s true insight, then, wasn’t evolution per se but evolution by natural selection. And it was barnacles that revealed how natural selection worked.

However tiny to humans, the variations Darwin noticed in barnacle shells and mouths and legs were vital to them—often the difference between life and death. In other words, those variations were the raw material on which natural selection acted. The key to the whole process.

Darwin then extended what he’d learned with barnacles to other species. “I am convinced,” Darwin later wrote, “that the most experienced naturalist would be surprised at the number of the cases of variability” throughout nature. He added, “When the same organ is rigorously compared in many individuals I always find some slight variability.”

This insight eliminated the fatal flaw in his theory. Nature wasn’t uniform at all—Darwin the dabbler simply did not have the neurons to see the nuances. Darwin the expert did.

This isn’t how we usually think about creative breakthroughs. We expect eurekas, sudden flashes of insight. Drama. What Darwin did hunched over those smelly barnacles seems like the opposite of creativity—petty drudge work. But that patient, years-long labor was actually critical.

Again, Darwin didn’t dream up evolution; even his grandfather dabbled in the idea. What Darwin did was prove how evolution worked, through years of sickness amid piles of marine critters. Thanks to his obsession with barnacles, his once-vague theory of evolution had itself evolved to a higher plane.

This is the Disappearing Spoon podcast, brought to you by the Science History Institute. Find out more about their library, museum, and multimedia magazine at sciencehistory.org.

Make sure you check out the Science History Institute’s other awesome podcast, Distillations. You can find their in-depth narrative stories and interviews about everything from Space Junk to Sex, Drugs, and Migraines anywhere you get your podcasts, and on their website: Distillations.org.

You can find more incredible stories from my books at samkean.com. You can also book me as a speaker at your school or event.

If you like this podcast, please support it at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. It costs as little as seven cents per day. You can also get bonus episodes and signed books.

Please spread the word to others as well, and subscribe in iTunes, Stitcher, or other places.

This episode was written by me–Sam Kean. It was mixed by Jonathan Pfeffer, and produced by Mariel Carr and Rigoberto Hernandez.

Thanks for listening.