An Old Testament battle between the Gileadites and the Ephraimites came down to one word: shibboleth, or river. Each group said it differently. Because both tribes looked and dressed alike, this slight difference in pronunciation was key for the Gileadites to sniff out their enemies and win. Sam Kean explains how naked mole-rats use the same tactic to decipher who their foes are, except instead of different accents they listen for different chirps.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Padmini Raghunath

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

The Old Testament is full of endless tribal battles that I never could keep straight growing up. But one of them, from the 1100s B.C., always stood out to me.

The Gileadites were battling the Ephraimites, and the Gileadites routed them and scattered their army. Eventually, the Ephraimites gave up and tried to retreat home. But the Gileadites were watching for them, eager to kill every last man.

There was just one problem. Most groups in the region dressed alike and looked alike. So if they captured some stranger, how would they know if he was an Ephraimite, and not a member of some other tribe?

So the Gileadites set a trap. They posted up at the River Jordan, at a certain crossing point. And whenever some stranger tried to cross, they’d point at the water and say, What’s that?

You see, the Gileadite word for river was shibboleth. Most people back then spoke several languages, so they would have known that. But the Ephraimites had a funny accent. It lacked the “shhh” sound. So when the Gileadites pointed to the shibboleth and asked what it was, the Ephraimites called it a sssibboleth.

The consequences for this blunder were not pretty. As the Book of Judges says, whenever the Gileadites caught someone butchering the pronunciation, “they took him, and slew him at the passages of Jordan. And there fell at that time of the Ephraimites forty-two thousand people.”

Since then, the word shibboleth has come to mean any sort of word that distinguishes one group from another. And this still happens today.

In the 1930s, in the Dominican Republic, Spanish-speaking soldiers exposed Creole-speaking Haitian immigrants by asking them to pronounce the Spanish word for parsley, perejil. When the immigrants couldn’t, the soldiers slaughtered them just as mercilessly as the Gileadites had the Ephraimites.

Along those same lines, during the Vietnam War, Americans teenagers often fled the draft by going to the Canadian border and claiming they were Canadian citizens. So border officials had them recite the alphabet as quickly as possible. If they ended with x, y, z, they were turned back. Canadians say x, y, zed.

It’s also been jokingly suggested that, if German spies ever invaded England today, people could easily expose them, even if the spies spoke nearly perfect English. Just have them try to name the small furry mammals that climbs trees. <CLIP: GERMANS> Germans simply cannot pronounce squirrel.

Now that’s all well and good with humans. But what if I told you that certain animals have their own shibboleths. Specifically, certain rodents. And just like the Gileadites, these rodents will kill anyone with the wrong accent.

That’s not the only way these rodents are strange, either. They also live in underground colonies with a queen, just like bees do. And what if I told you that these murderous rodent-bees never get cancer or die of old age—and that they therefore might hold the secret to immortality.

It’s all true. Welcome to the bizarre world of the naked mole-rat.

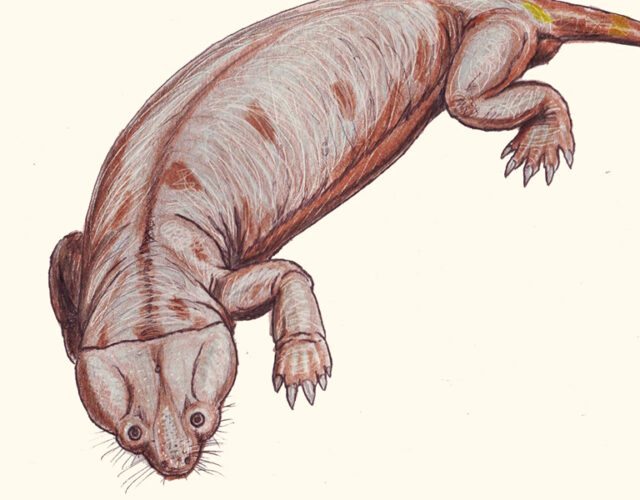

Let’s clear one thing up. Technically, naked mole-rats are neither moles nor rats. They’re a different type of rodent. But they are naked. That is, have almost no hair.

All they have is some cat-like whiskers on their nose and tail, to help them navigate underground tunnels. They also have tufts of hair between their toes. That might seem like a weird place to have hair. But they spend much of their lives digging, and the tufts between the toes turn their feet into brooms. Pretty clever.

Naked mole-rats are about three inches long, and weigh roughly one ounce. You could hold several in your palm. But you probably would not want to. Because frankly, they look hideous.

They’re native to the grasslands of Ethiopia and Somalia. And the first European biologist to see one assumed he’d found a colony of mangy, leprous mice. No normal creature, he figured, could be that ugly.

To start with, naked mole-rats are basically blind, since they live underground. So they have these creepy, beady little eyes. Gross.

Even worse is their mouth. They have these huge, grotesque buckteeth. And weirdly, these teeth sit outside their mouths. They can actually close their lips—and the teeth are still there, just looking at you. They have this trait because they sometimes dig out tunnels with their teeth, and it prevents dirt from getting in their mouths. But it still looks nasty.

And their skin? That’s the biggest yuck of all. It’s pink, and wrinkly, and full of veins. I’m not the first person to think that they look like little wriggling scrotums. Seriously, you can see pictures at Patreon.com/disappearingspoon. They’re truly revolting.

And yet, for all that, these hideous-looking rodents are absolute darlings in the world of science. Why? There are several reasons.

First is their social structure. You might know that ants and bees and termites live in colonies. They have one queen who does all the reproducing. All the other ants or bees are sterile worker-drones who work on the queen’s behalf.

This seems to fly in the face of natural selection—especially the idea of selfish genes. Why do workers labor like that for the queen, at the cost of passing on their own genes?

The answer is that all the workers in a colony are siblings. So by helping each other, they ensure that at least some of their DNA gets passed to future generations. It’s not the usual setup among animals, but it’s wildly successful. Bees and especially ants are some of the most abundant creatures on earth.

This social structure—with a central queen and sterile workers—is called eusociality. And eusociality was thought to be exclusive to insects—until scientists discovered it in the naked mole-rat.

Just like bees, naked mole-rats lives in colonies with up to 300 members. There’s a queen mole-rat and the male studs who service her. But beyond those few, all other naked mole-rats are sterile soldiers or diggers whose lives revolve around the queen.

Now, you might wonder how much digging there really is to do, to the point they need dedicated diggers. And the answer is a lot. Each colony consists of two to three miles of tunnels. And remember, they’re just a few inches long.

They’re also so blind that they can’t get food on the surface—they’d be easy pickings for predators. So they have to stumble into their food underground.

Mostly, they live on underground tubers, similar to carrots or potatoes. But they’re actually very careful about eating them. They never eat a whole tuber at once. Instead, they nibble only certain parts. This gives the tuber a chance to grow those parts back and make more food. It’s essentially sustainable agriculture.

Beyond being eusocial, naked mole-rats are un-mammal-like in other ways, too. They’re basically cold-blooded, like reptiles. That is, their bodies don’t stay at a consistent temperature. Instead, they get warmer or colder with the environment.

Even odder, naked mole-rats need very little water. And even less oxygen. The air we breathe is 21 percent oxygen. Underground, the air doesn’t mix much. So mole-rats have to get by on air with less than 10 percent oxygen—sometimes less than 5 percent.

How do they do this? Well, most mammals store energy in the form of a sugar called glucose, and we use oxygen to burn glucose. In contrast, naked mole-rats store much of their energy as a different sugar called fructose. Fructose doesn’t need oxygen to burn it. So the mole-rats need less oxygen overall.

In fact, you can completely deprive naked mole-rats of oxygen for up to 18 minutes, and they’re perfectly fine. A similar-sized mouse would die after a single minute.

Overall, the bodies of naked mole-rats are like hybrid cars. They can switch back and forth from one energy source to another depending on what’s available. Pretty amazing.

And to be fair, even their hideous, scrotum-looking skin is amazing. You can pour acid right on that skin, and they feel no pain. The same goes for capsaicin, the molecule that makes chili peppers hot. Most mammals bite into chili peppers and—god help us, it burns. But not naked mole-rats. They’re immune to capsaicin. They bite into a chili pepper, and—they’re still cool as cucumbers.

But, for all their cool traits, there are some less-than-cool things about naked mole-rats as well. For one thing, they’re pretty vicious.

I mentioned before that mole-rat colonies have a “queen.” But in some ways that’s a misleading metaphor. Naked mole-rats queens are bigger—about three ounces, compared to one ounce for a normal mole-rat. But queens don’t really rule over the colony, or have special privileges.

In fact, life as a queen sounds miserable. She’s pregnant basically her whole life, and gives birth up to 900 times. Imagine going through labor 900 times. Is it really good to be queen?

Nevertheless, female naked mole-rats fight viciously for the position. And the reigning queen bullies and beats up all usurpers to her throne. In fact, other females feel so much stress around the queen that their bodies stop producing reproductive hormones. That’s how the queen keeps them sterile.

Naked mole-rats are even more vicious with outsiders. And here’s where we get back to the idea of a shibboleth.

To be blunt, naked mole-rats are completely xenophobic—utterly intolerant of outsiders. If an outsider does wander into their colony, they gang up and murder it. Mauling it, gnawing its face. They have zero mercy.

But that brings up a question. If naked mole-rats are blind, how do they recognize outsiders? Scientists once assumed that they used smell, and odors do probably play some role. But the real key involves chirps.

Every naked mole-rat colony has its own highly specific chirp. Listen to these two. The audio is a bit rough, but hopefully you can tell the difference. Here’s one… <CHIRP1> …and here’s the other. <CHIRP2> It’s like British versus American English—the same, but different.

The chirp is set by the queen. It’s like humans and fashion—once the upper crust does something, all her subjects adopt it. And the mole-rats use the chirp just like the Gileadites used the word shibboleth. If an outsider wanders in, they insist on hearing its chirp. If it’s the wrong chirp, they murder it.

Now, many animals can make noises. But usually those noises are hard-wired. They’re fixed and they don’t change. There are very few exceptions to this—whales, songbirds, and of course human beings. We can all learn new sounds as adults.

And so can naked mole-rats. You see, whenever a queen dies or a mole-rat colony gets too large, the colony will split in two, and some mole-rats will go to a new location. And when those migrating mole-rats get settled in, their queen will teach them a new chirp, a new shibboleth. So like birds and humans, they produce new acoustic signals in adulthood, which for most animals is very hard to do.

So, naked mole-rats murder you if you sound foreign. And here’s something else they do that’s ugly—kidnapping.

If given the chance, naked mole-rats will steal into another colony and raid all the infants there, taking them home. Then they’ll raise these stolen infants as their own. This includes forcing them to learn their unique chirp. Then they set these stolen mole-rats to work digging.

This isn’t quite slavery, since the stolen ones do the same work as other sterile drones. But most mole-rats in a colony are at least working for their siblings. The kidnapped ones are laboring for strangers, and therefore get no benefit. It’s diabolically clever.

But however vicious mole-rats can be, I don’t want to end on that note. Because of all the good-amazing and bad-amazing things about them, the most amazing thing is this. They do not get cancer, and they essentially do not age.

They avoid cancer in a few ways. First, they have certain snippets of DNA that prevent cells from proliferating out of control. That helps their bodies suppress tumors, which are basically masses of cells growing out of control.

Second, their cellular machinery is extremely accurate when it comes to copying DNA. Considering how important DNA is, most other creatures copy it carefully as well. But naked mole-rats are in a class by themselves. Their cells rarely make mistakes. This cuts down on mutations that lead to cancer.

As for them not aging, that might sound surprising, since naked mole-rats are already born looking pretty old and wrinkled. But looks can be deceiving. However decrepit-looking, they’re remarkably robust.

For one thing, they don’t die of old age. In general, smaller mammals live shorter lives. Whales and elephants live for decades, while mice last about two years in the wild. Naked mole-rats are mouse-sized, but they defy the odds and live 30 or more years.

Now, obviously, mole-rats aren’t immortal. They can die of other things—accidents, droughts, predators, murder. But not old age, as far as scientists can tell.

And those extra years of life are good years. They don’t experience menopause or slow down in any measurable way. That would be like a human being acting just as spry at age 100 as they did at age twenty. In fact, given the mole-rats’ size, it would be like a human still being spry at age 400. Old age simply does not affect naked mole-rats.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Why aren’t scientists studying the hell out of these hideous little things? Let’s find the secret sauce they have and inject it into all of us, and eliminate aging and cancer.

If only it were that simple. There isn’t some secret chemical here. It’s more like a suite of genetic changes. So to stop cancer or halt aging, we’d probably have to fiddle with our DNA, which is always dicey.

And unfortunately, their gifts are probably related to their lifestyle. Being sterile, and cold-blooded, and living underground without oxygen eliminates a lot biological stress. Would any of us trade, say, the joy of sex, or even the refreshing feel of a nice, deep breath, for a few extra years as a wrinkly, wriggling rodent? Probably not.

Still, they have beat cancer. They have beat aging. Naked mole-rats prove that it’s not biologically impossible. They can give us hope.

And honestly, we might be more like naked mole-rats than we think. After all, we’re pretty naked, too. And not many other creatures kill each other over shibboleths. Let’s just hope that, through the wonders of science, we can emulate their amazing qualities, and leave the ugly stuff behind.