In 1878 railroad tycoon Leland Stanford (namesake of Stanford University) needed to know the answer to a simple question about horses: are they ever airborne? To prove it he hired photographer and technical wizard, Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge was famous for the photographic skills that would go on to make Hollywood possible. He was also famous for being a murderer.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Padmini Raghunath

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

They could not have asked for a better morning. June 15th, 1878, dawned bright and clear, a sparkling day. A crowd had gathered at a racetrack in Palo Alto, California, land that would eventually become Stanford University. In fact the university’s namesake, Leland Stanford, was the reason everyone was there.

Stanford had made his fortune as a railroad magnate, then served as governor of California. But his true passion was horses. And he’d gathered the crowd that day to settle a longstanding debate among horse fanciers. When horses gallop, do all four hooves ever leave the ground at once?

It was a contentious question—fodder for endless arguments at bars and racetracks, among biologists and degenerate gamblers alike.

Stanford insisted yes—that all four hooves do leave the ground. Unfortunately, the human eye cannot work fast enough to follow a horse’s churning legs. <POUNDING> So after years of futile speculation, Stanford had hired a photographer to determine the answer.

Ostensibly, the crowd had gathered that June morning to see whether Stanford was right. But if truth be told, many in crowd were just as eager to see the photographer himself.

Eadweard Muybridge had an international reputation for taking beautiful pictures. He was also a technical wizard, a pioneer of the motion-picture technology that would make Hollywood possible.

Strangely, though, Muybridge’s talents had emerged only after suffering a major brain injury as a young man. He was something of a neurological freak.

There was also the matter of a recent court case involving Muybridge. Because however famous for his photography, most people then knew Muybridge best of all for being a cold-blooded murderer.

<INTRO>

At the height of his fame, Eadweard Muybridge looked scruffy and Bohemian, with a big white beard. Someone once described him as “Walt Whitman ready to play King Lear.”

Before his Bohemian phase, however, Muybridge had a respectable career. Born in England in 1830, he emigrated to the United States at age 22 and opened a bookshop in San Francisco. But that nice, respectable life crumbled in 1860.

That year, Muybridge decided to return to England to hunt for some rare books. Unfortunately, he missed the steamship out of San Francisco. So he decided to take a stagecoach to St. Louis instead, and sail from there.

He never made it. <HORSES, CRASH> Somewhere in northeast Texas, the driver lost control of the horses on a steep downward slope. Second later the brakes failed, and the stagecoach began careening out of control.

Seatbelts of course didn’t exist back then, and the coach crashed headlong into a tree. One passenger died instantly.

Muybridge was thrown clear but landed headfirst on a boulder and split his skull open. He spent nine days in a coma, and woke up 150 miles distant in an Arkansas hospital. For the next three months, he suffered seizures and agonizing headaches. His hair went stark white. He also had double-vision, and temporarily lost all sense of hearing, taste, and smell.

Nowadays, it’s almost certain that Muybridge suffered a severe concussion. But more than that, he showed signs of permanent brain damage.

Above all, friends noticed a personality shift. Before he’d been patient, friendly, and good at business. Afterward, he was rash and impulsive and had a volcanic temper. He’d fly into rages over the smallest thing.

Reading between the lines here, Muybridge probably suffered damage to his frontal lobes. The frontal lobes are responsible for our so-called executive function. They help us plan things and reason things through. They also help us calm down when we feel emotional. It’s always tricky to retro-diagnose someone from the past, but it sure seems likely that Muybridge suffered damage to his executive center.

No matter the specifics, Muybridge definitely changed after the accident. He sailed to England and spent the next five years recovering.

And here’s where his life took a swerve. Photography was a new technology then. Muybridge had seen examples in San Francisco and thought they were ho-hum.

Suddenly, though, in England, he grew fascinated with photography. It became his obsession. And as strange as it sounds, some scientists today have linked his new-found obsession directly to his accident.

Neurologists know of something called sudden savant syndrome. It occurs when people suffer brain damage and suddenly gain artistic skills. Someone might be struck by lightning, and then have an insatiable desire to compose symphonies. Another person might suffer a stroke, then spend a dozen hours a day painting portraits.

The best guess here is that damage to the frontal lobes releases impulses that are otherwise suppressed inside us. When the executive part of the brain no longer functions, the wild artist can run free.

It sounds amazing. But, there’s always a tradeoff. People gain artistic skills, but like Muybridge, they often become impulsive and reckless as well. There’s dark side to sudden savant syndrome.

After recovering in England, Muybridge returned to California and established himself as one of the best photographers around. He was especially known for his gorgeous pictures of Yosemite Valley—including some he took while dangling over two-thousand-foot precipices. He couldn’t help his recklessness.

More prosaically, his fame as a photographer led to gigs shooting people’s houses. And that’s how, in 1872, Muybridge met Leland Stanford, the railroad tycoon and horse fancier.

Again, Stanford was obsessed with a seemingly simple question. When horses run, do all four feet leave the ground at once? Stanford insisted that they did, and proposed that he and Muybridge collaborate to prove this.

In response to the proposal, Muybridge scoffed. He told Stanford it was flat-out impossible.

You see, photography back then was nothing like the point-and-shoot technology of today. Most cameras didn’t even have shutters. People would just put a hat over the lens when the exposure was done.

What’s more, film wasn’t very sensitive. Even the fastest film usually required at least 15-second exposures. Capturing a horse at mid-gallop would require exposures of a few tenths of a second. They might as well try to photograph a speeding bullet.

Stanford was determined, however. According to legend, he had a $25,000 bet on the horse question. So he offered Muybridge $2,000—equivalent to almost $50,000 today—to work out the technical details. However skeptical, Muybridge agreed.

Unfortunately, this little venture soon hit a bit of hiccup. Muybridge committed murder.

Around the time he met Stanford, Muybridge had married a woman named Flora. She was 21 years younger than him, a technician in his photography studio. At first, they had a nice, happy union.

It didn’t last. As part of his job, Muybridge was constantly traveling, and Flora was getting bored at home. She liked the theater, however, so Muybridge arranged for a local drama critic named Harry Larkyns to escort Flora to the theater a few nights a week.

You can probably guess what happened. While the older, unkempt husband was gallivanting around the country, the suave Larkyns swept in and seduced Flora. They began a torrid affair.

Muybridge and Flora eventually had a child in 1874. They named him Floredo—possibly a mashup of Flora and Eadweard. But two weeks before Halloween, in October 1874, Muybridge came across a letter that Flora had sent to Harry Larkyns. She’d included a photograph of Floredo. The caption read, in Flora’s handwriting, “Little Harry.”

Muybridge went ballistic. He began stamping his feet, howling and screaming. A full five-alarm rampage. Then he grabbed his six-shooter and took off to find Larkyns.

He finally tracked Big Harry down at a ranch eight miles from Napa Valley. When Larkyns answered his knock, Muybridge said, “This is a message from my wife.” Then… <BANG!> The bullet tore through Larkyns’s heart. He was dead before he hit the ground.

The murder caused huge headlines across the West. And why not? A famous bohemian artist had murdered his wife’s lover. People couldn’t get enough.

Muybridge’s only hope was an insanity defense. Friends testified how he’d changed dramatically after his carriage accident, losing all control of his emotions. But when the jury retired to debate the verdict, the death penalty was still very much in play.

The trial’s outcome might strike us as bizarre today. The jury came back and said, yes, Muybridge had murdered his wife’s lover—and done so in cold blood. But all twelve men agreed that they would have done the same thing. So despite Muybridge being completely guilty, the jury let him go.

By that point, sadly, Flora was dead. She’d divorced Muybridge after the murder, but didn’t get much time to enjoy her freedom, as she soon caught typhoid and died. Coldly, Muybridge wanted nothing to do with Floredo, and left him to his fate in an orphanage.

Instead, Muybridge fled to Central America on a photography junket, to let things cool down. And when he returned to California, Leland Stanford got in touch again. Stanford still wanted to prove his theory about horses rights. And with nothing better to do, Muybridge finally agreed to go all-in.

After a few years of tinkering—and a lot more money than Stanford expected—Muybridge eventually solved the two big technical problems. First, he helped develop a chemical for film that was far more light-sensitive. It could therefore capture a clean picture after only a brief exposure.

Second, he developed a far faster shutter system. It actually involved two shutters that slid past each other. Each one had a hole in it, and when the holes aligned for a split-second <CLICK>, you’d get a picture.

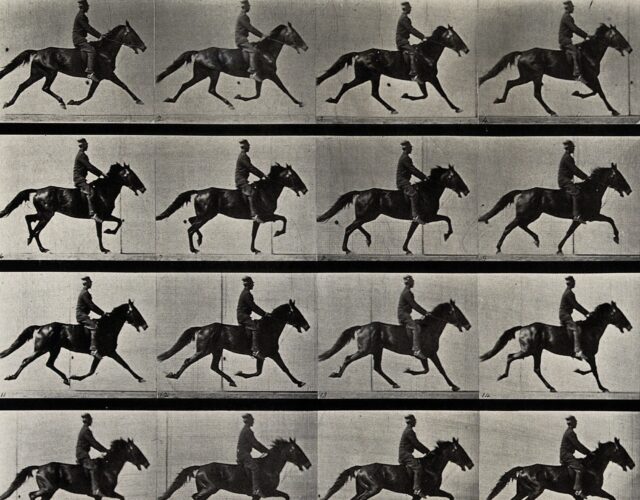

Everything came together that morning in June 1878. Muybridge set his equipment up in a white shed near the racetrack, with an open side facing the dirt. Inside were a dozen of Muybridge’s quick-acting cameras, each several inches apart. On the opposite side of the track hung a long white sheet, to make the brown-colored horse stand out.

The horse’s name was Abe Edgington. At Muybridge’s signal, Abe took off, galloping along at 40 feet per second.

Harnessed to Abe was a two-wheeled cart. There were twelve electrical wires buried in the racetrack dirt along Abe’s path. When the cart’s wheels crossed each wire, they completed a circuit, and one of the twelve cameras would fire. <SNAP> Using this setup, Muybridge managed to snap twelve pictures in less than one second. <RAT-A-TAT> It sounded like a machine gun.

Afterward, Muybridge retreated to a dark room to develop the pictures. Leland Stanford paced nervously. Given the inevitable budget overruns, he’d spent $50,000 on the project—$1.2 million today. Would it all prove a waste of money—or worse, would he be proved wrong and embarrassed?

Finally, after twenty minutes, Muybridge emerged from the dark room. And when he showed Stanford the pictures, the railroad tycoon threw his arms up in triumph. Just as he’d predicted, all four hooves clearly left the ground mid-stride. Horses were not eternally earthbound; however briefly, they do fly.

Word about the photographs spread quickly, although the reactions outside Palo Alto were mixed. The masses loved the experiment, and Muybridge became world-famous.

Artists, meanwhile, had a different reaction. Many painters and sculptors, in fact, got downright angry. The spread of photography was already poaching on their territory. Now, Muybridge was making them look foolish.

As one critic noted, the pictures “laid bare all the mistakes that sculptors and painters had made in their renderings” of horses. Indeed, compared to Muybridge’s photos, their depictions of running horses suddenly looked ridiculous—with horses splayed out sometimes as if doing a belly flop.

Now, some artists swallowed their pride and tried to get better. Thomas Eakins and Edgar Degas studied Muybridge’s work closely. Other artists took to the offensive. Auguste Rodin, who sculpted The Thinker, was especially mad. He thundered, “It is the artist who is truthful and it is photography which lies. For in reality time does not stop.”

It’s an interesting point—time doesn’t actually stop. But it also sounds like sour grapes. And no matter what, Rodin was fighting rearguard action. Muybridge’s photo forever changed the art world.

But if artists got upset, biologists were thrilled with Muybridge’s work. His horse photos appeared in Scientific American, and they opened up a whole new way to study animals motion.

In a wider sense, Muybridge also demonstrates a general truth of how science gets done. We normally think about scientific progress in terms of theoretical breakthroughs, like Einstein or Darwin.

But sometimes knowledge advances when scientists simply get new gizmos. Telescopes were originally military hardware, not for stargazing. Similarly, Muybridge’s cameras were meant to settle a bet. But science benefitted mightily.

And science is still benefitting today. Several research teams in the past decade have used high-speed cameras to resolve a new generation of vexing questions about animal behavior. Call it Muybridge 2.0.

I’ve actually put together a bonus episode about these new research projects at Patreon.com/disappearingspoon. They’ve helped scientists to understand how dogs and cats eat and drink, and helped probe the best way to kill flies. You can also see some high-speed pictures of pandas, kangaroos, tigers and other animals doing a variety of adorable things. That’s Patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

Unfortunately, after the triumph at the racetrack, Muybridge and Stanford had a nasty falling out. Like a typical executive, Stanford hogged all the credit for Muybridge’s photographs, even publishing a book about them where he barely mentioned Muybridge’s name. To Stanford, Muybridge was a mere technician.

Muybridge had the last laugh, however. He ended up moving to the University of Pennsylvania and diving even deeper into his studies of animal motion. He took tens of thousands of pictures overall—including many of humans in motion. In fact, Muybridge himself appears in several—usually stark naked. After his brain damage, he had no shame about exhibiting himself.

Eventually Muybridge realized that he could string these photographs together. If he flashed them in quick sequence, they looked continuous—an early motion picture. There was no sound, of course. And as a one historian noted, the whole film was over in just seconds—quicker than you could eat a bite of popcorn. But people were nevertheless astounded.

Over the next few years, other pioneers built upon Muybridge’s work with high-speed cameras to develop true movie cameras. But by then Muybridge had slowed down. He eventually returned to England and died in 1904. His last great project involved building a replica of the Great Lakes in his backyard. No one knew why. It was just Muybridge being Muybridge.

Today, though, he holds a special place in history. He remains one of those rare people like Albrecht Dürer and Leonardo who pioneered both art and science. And it likely all came about because of a carriage accident that nearly split his head open. I’ve written books that cover nearly every topic in science, from atomic physics to the fate of the cosmos. But when I hear a story like Eadweard Muybridge’s, I’m reminded that perhaps the biggest mysteries in the universe lies right between our own ears.