In The Icepick Surgeon, host Sam Kean focuses on the professional side of Walter Freeman, a surgeon who performed four thousand lobotomies during his lifetime, including many on children. This episode of The Disappearing Spoon takes listeners into the Oedipal battle at the heart of Freeman’s life—which involved both contempt for his father and his failures with his own sons.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Padmini Raghunath

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

People often ask me, “How do you do your research?” And honestly, I wish there was a more exciting answer. Because the truth is, most research is pretty dull: reading through mountains of dusty documents, hunting through hundreds of footnotes to find that one elusive fact. The real secret is what the Germans call sitzfleish, or sitting flesh—the sheer ability to park your rear end on a chair and endure a task, however boring.

But every so often, something amazing happens during the course of research—a little gold nugget in the muddy stream. That actually happened with my most recent book, The Icepick Surgeon, about the title character, lobotomist Walter Freeman.

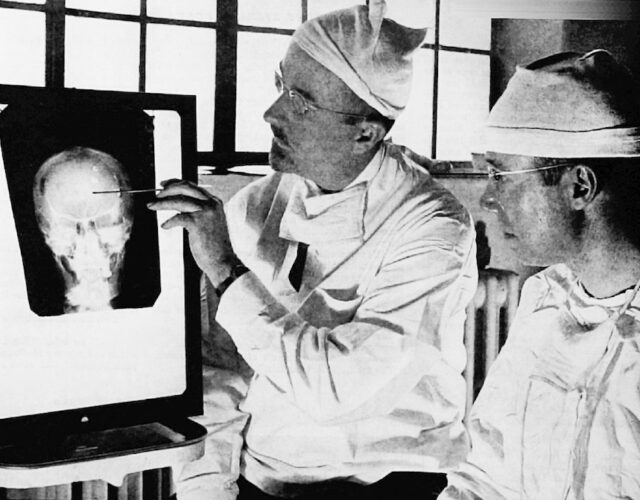

In the book I focus on the professional side of Freeman, who performed four thousand lobotomies during his lifetime, including many on children. His most notorious case involved President John F. Kennedy’s sister Rosemary, who spent the rest of her sad life trapped in an asylum afterward.

But there’s another side to Freeman, the personal side, that I caught an unexpected glimpse of while researching The Icepick Surgeon. I had ordered a copy of a book written by Freeman, just to get a feel for his writing. I honestly didn’t think it would be that illuminating or interesting.

Boy, was I wrong. Because when I opened the book, the first thing I saw inside were several forgotten postcards—written by Walter Freeman himself. The postcards discuss Freeman’s sons and daughters, as well as his beloved hiking trips across the country. They’re an intimate glimpse into the private life of the most notorious doctor in American history.

So today, I’d like to use those surprise postcards as a springboard into the dark personal side of Walter Freeman. Specifically, into the Oedipal battle at the heart of Freeman’s life—which involved both contempt for his father and his failures with his own sons.

In fact, one failure in particular—which resulted in the death of his favorite son—actually fueled Walter Freeman’s massive, nation-wide push for lobotomies, and made him the pariah he is today.

Walter Freeman’s maternal grandfather was William Keen (no relation), one of the most eminent neurosurgeons of his day. Keen invented several pioneering brain surgeries, and treated three different U.S. presidents—William McKinley, Teddy Roosevelt, and Grover Cleveland, who had a cancerous jaw tumor removed by Keen.

When Freeman was a teenager, he took a Caribbean cruise with Grandpa Keen, which included rugged horseback riding whenever they went ashore. They also visited the Panama Canal, which was then being constructed. Ordinary folks were not allowed to tour the site, but the famous Dr. Keen was allowed, and he took young Walter along. Freeman remembered being awed at how even military people fawned over his grandpa, and he always admired him for that.

With Freeman’s own father, it was a much different story. His father was a doctor as well—ear, nose, and throat. But his father was timid and feckless, and actually hated practicing medicine. He was constantly moaning and complaining about his patients, and worked as little as possible.

The only thing Freeman’s father seemed to enjoy was camping, which young Walter also loved. But even when camping, his father could do no right. Because as soon as they got to a campsite, his father would disappear into the tent and spend the whole day reading. Meanwhile, he would pay a guide to actually take his sons out into the wilderness. Walter considered this pathetic.

Overall, Freeman scorned his father, especially compared to his grandpa Keen. And Freeman was absolutely determined to outshine his father, and live up to his grandfather’s glittering example.

As a young doctor, Freeman therefore worked maniacally hard. So hard, in fact, that he blew off all family responsibilities. Incredibly, he didn’t even realize his father was dying of liver cancer until the case was terminal.

And when Freeman did learn of the cancer, he resented having to take care of his father. When he had to shave his father’s face in the morning, he did so as quickly as possible, sometimes leaving gashes on the old man’s sunken cheeks. But Freeman simply couldn’t bother to feel any compassion. And when his father died, Freeman admitted feeling relief.

Freeman’s drive to outdo his father led directly to his work on lobotomies. In the 1920s, his grandfather got him a post at an insane asylum in Washington D.C. called St. Elizabeths. The place horrified him. People there were often locked in straitjackets all day, screaming and suffering.

Some patients couldn’t have beds, because they’d break shanks off the frames and attack people in their delirium. Some patients couldn’t go outside, because they’d run away or hurt themselves. Some couldn’t even have clothes, because they’d tear the garments off or soil themselves repeatedly. And there was nothing doctors could do to help them. There were zero drugs—zero effective treatments.

St. Elizabeths wasn’t alone, either. Every good-size town in the Americas and Europe had its own asylums with its own heartbreaking cases—millions upon millions of them. They were the most hopeless people in the most hopeless places on Earth.

And despite his many less-than-sympathetic qualities, Freeman genuinely wanted to help these people. He wanted to cure them, cure them all—a noble mission. But he of course also knew that, if he could cure them, he’d go down in history as one of the greatest doctors of all time. He could outshine even his illustrious grandfather.

So in 1935, when a doctor in Portugal invented a surgery that became known as the lobotomy, Freeman jumped on the idea, embracing it with all the conviction of a religious zealot. Lobotomies became his obsession, his reason for living.

I explain more about this obsession in The Icepick Surgeon, but Freeman operated on some patients with, quite literally, an icepick he’d found in his kitchen drawer. More broadly, he was determined to make the lobotomies the first line of defense against mental illness.

But to do so, he needed to convince other doctors that lobotomies were worthwhile. So in 1946, Freeman came up with a plan. That summer, there was a big medical conference in California. Freeman always loved road trips—the long open highways, the wind rushing through the car’s windows, the freedom of it all.

So he decided to drive from Washington to California to spread the gospel of lobotomies at the conference. Then, for the trip back home, he made arrangements with a sympathetic colleague in South Dakota who ran an asylum. Freeman planned to teach the doctors there how to perform icepick lobotomies, so they could start operating on patients themselves.

Now, it would have been just like Walter Freeman to take off on this trip and leave his wife and children behind. He always put work above family. For example, in 1936, as his wife was going into labor with one child, he got word that an alcoholic lobotomy patient had escaped from the hospital and was carousing around town. Freeman promptly ditched his wife to search for the man. By the time he found the patient, who was black-out drunk in a bar, his son Randy had been born. Freeman missed the whole thing.9

By 1946, however, Freeman was striving to be a better father. Especially for his favorite son, a lad named Keen.

Keen was named after Freeman’s beloved grandfather, and he was a sharp kid. So Freeman decided to take both Keen and Randy along with him on the road trip to California and then South Dakota.

On the trip out, the nine-year-old Keen greatly impressed Freeman. At a campsite in Nebraska one day, Keen dug dozens of old animal bones out of a cliff side—and proceeded to identify every last one of them. Like a true paleontologist. The boy was brilliant—a worthy heir to his grandfather.

Unfortunately, those hours on the road would be some of the last time father and son would ever spend together.

After the conference ended in California, Freeman had a few spare days, and he decided to take his sons hiking. In contrast to his own father, Freeman wasn’t going to just sit in a tent and read, either. He planned a rugged hike in Yosemite National Park. It was going to be an adventure.

One afternoon, the Freemans hiked to the top of a majestic, 317-foot waterfall, Vernal Falls. The day could not have been more perfect. The boys raced up the trail ahead of him, while Freeman hung back and enjoyed the warm sunshine on his face, and the rich smell of pine trees.

At the top of Vernal Falls, Keen was thirsty. So he asked Freeman if he could crawl past the protective fence and fill his canteen in the river near the precipice. Freeman chuckled and said sure—just be careful. He was actually proud of his son for being daring like this. Unlike his own father, the boy wasn’t passive or afraid.

Meanwhile, Freeman kept enjoying the scenery. It was a warm day, but California lacked the humidity that makes Washington D.C. so nasty in the summertime. Freeman jokingly called California “The land of the dry shirt,” and he was determined to enjoy every moment.

But he wouldn’t get the chance. While taking in the scenery, Freeman heard something ominous. A splash. He snapped his head around to where Keen had been filling his canteen—and saw no one there.

His eyes darted to the water. And to his horror, he saw Keen’s bobbing head. Even worse, the current above the waterfall was swiftly pushing his son toward the brink.

Freeman would always blame himself later for being paralyzed with fear at this moment. He considered himself bold, a man of action. But with his favorite son’s life on the line, he froze in terror.

Not everyone froze, however. A young man who’d recently been discharged from the navy heard Keen’s desperate cries for help. Without hesitating, the sailor hopped the fence, sprinted to the water’s edge, and dove in himself. Within a few swift strokes, he’d grabbed Keen, and gotten his head above water.

To everyone watching, it seemed like a miracle—someone had reached the boy! But the danger wasn’t over, not by a long shot. The current was simply too powerful. The sailor fought as fiercely as he could—grabbing branches, bracing himself against underwater rocks. But these were never more than a moment’s relief. The current kept prying his hands free, and he and Keen kept tumbling further toward the 317-foot precipice.

Finally there was one last rock. The sailor snagged it, and stopped their awful momentum. But between the current and keeping Keen above water, he was simply too exhausted. The current wrenched his fingers loose, and a moment later, he and Keen were swept over the edge.

Freeman’s last image of his favorite son would forever be burned into his memory. The terrified little boy, dangling in empty air, his face twisted with shock and fear. A moment later, his son plummeted and disappeared from sight.

Given the massive churn of water at the bottom, it took authorities three days to find the bodies. Keen’s skull was smashed in, which prevented an open casket. But Freeman consoled himself that, because of the head injury, death had likely been instantaneous.

Still, that was about all the consolation Freeman could derive. He’d encouraged his son’s bravado, and look at what it had gained him. He was left in agony, and he seriously wondered whether he could ever continue in medicine.

But soon enough, the old Walter Freeman emerged from his shell of grief. And when it did, Freeman grew even more ambitious than before. Rather than give up medicine, he rededicated himself to the cause of lobotomies. He decided he had to make Keen’s death mean something, to somehow justify it. So Freeman kept his appointment at the asylum in South Dakota, and did several lobotomies there, the first ones he ever did outside of Washington.

And after that, the lobotomy road trips became an annual summer ritual. Freeman put in thousands of miles every year, crisscrossing the byways of America. In his crass way, Freeman jokingly called the trips his “head-hunting expeditions.” But he worked harder than ever. He once did 25 lobotomies in a single day, until his hands ached from the effort. He trained other doctors to do lobotomies as well, so they could perform them when he wasn’t around.

Freeman never took his sons on these later road trips. But in a way, Keen was present the whole time.

Freeman charged very little money for lobotomies, since most asylums were strapped for cash. Most of the expenses therefore came out of his own pocket. Or rather, out of Keen’s pocket.

You see, Freeman had long recognized his son’s talents, and had been saving up money for the boy’s college education. After Keen’s death, Freeman redirected that money toward the lobotomy road trips—as well as all the money he would have saved for Keen’s college fund had the boy lived. Eventually, Freeman and his disciples lobotomized nearly 50,000 people—all of them ultimately financed, directly or indirectly, by Keen’s death.

And again, Keen’s impact wasn’t just financial. Freeman had almost given up lobotomies after the boy’s death. Instead, he did the opposite, and redoubled his efforts. He needed Keen’s death to mean something. Twisted by grief, he imagined that at least some good would come from the loss, if it gave him more time and money to focus on lobotomies.

Of course, the real tragedy is that what came from the loss was not good. It was barbaric and reckless, and Freeman’s icepick surgeries ruined countless lives. Fittingly, in fact, the best description of Freeman’s work came from another son of his, Walter, Jr., who grew up to become a doctor himself. As Junior once said, bitingly, “Talking about a successful lobotomy was like talking about a successful automobile accident.”

Now, I said at the top of the show that I was first inspired to do this story by some postcards that I found in a book, personal postcards from Walter Freeman. And if you want to see those postcards, I’ve posted them at Patreon.com/disappearingspoon. Be sure to check them out. They’re utterly fascinating.

And beyond inspiring this podcast, those postcards shed more light on Walter Freeman’s Oedipus complex. Because however personal those cards were, he sent them mostly to his lobotomy patients. He was always trying to keep in touch with those patients. Partly because he wanted to mine their lives for anecdotes about whether their lobotomies had been successful.

But he also considered himself a father figure to these men and women and children. He felt that they were the people he could save, even when he’d failed to save Keen. Those patients became his real children; he certainly poured more energy and emotion into them than his own family.

All of which makes the postcards I found in that book even spookier. Because I was holding something that not only Walter Freeman touched, but that one of his victims touched as well. And I could sense the ghost of his poor dead son Keen hovering over it all.