Warfarin is on the World Health Organization’s list of “essential medicines,” but the blood thinner didn’t start out that way. Once considered a poison, this lifesaving drug can now be found in the medicine cabinets of two million people in the United States alone.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Padmini Raghunath

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

Ed Carlson was desperate. It was a Saturday in February 1933, the depths of the Great Depression. And he’d just found two more dead cows in his barn.

A month earlier, two seemingly healthy heifers had collapsed and died of internal hemorrhages. Weeks later, a bull died of a simple puncture wound that kept gushing and gushing blood. Then that Saturday, two more heifers fell, again with internal hemorrhages. Five cows, all bled to death.

Now, this was not a good day to deal with a crisis. A real Wisconsin blizzard was raging outside. Temperatures had dropped well below zero.

But if Ed Carlson lost any more cows, he was ruined—his farm, gone. So, using all his strength, he loaded one dead heifer into his pickup. He also filled a milk pail with blood from the other dead cow, and grabbed some tufts of the clover he’d been feeding them. Then… <CAR SPUTTERING/CATCHING> …he set off into the blizzard.

You can imagine the conditions. Slippery roads. Blinding snow. His pickup shaking in the wind. And mile after mile with no company except the dead cow.

Veterinarians had been warning farmers for a decade by then: Don’t feed your cows sweet clover. They’ll bleed to death. Ed Carlson thought it was all a bunch of bull sugar. His daddy had fed cows sweet clover, and his daddy’s daddy had, too. He didn’t like those egghead science-types telling him what to do.

But like many people, Ed Carlson dismissed science right up until he needed it. After 200 miles of blizzard, he finally pulled up to a veterinary research station at the University of Wisconsin.

Only to find the station closed—it was Saturday night. Two-hundred miles with a dead cow, all for nothing. But old Ed was desperate. He started wandering around campus, yanking on different doors to see if they were open. Determined to find someone.

Finally, inside the biochemistry building, he found some scientists. Ed told them to sit tight. He brought the milk pail of blood inside, plus some clover. Then he actually lugged the dead heifer in, and dumped it right there on the lab floor. <SLUMP>

The lab’s top chemist was a man named Karl Link. And the whole scene left Link bewildered. He felt bad for the farmer, sure. But Link was a carbohydrate chemist. He studied corn. What the hell did he know about dead cows?

Nevertheless, in one of those amazing coincidences that end up changing the world, Ed Carlson had stumbled into the exact right person to help him. Because that dead cow concealed a lethal poison—a poison that would go on to become one of the most important drugs in the history of medicine.

<INTRO>

After Ed Carlson dumped the dead cow in his lab, Karl Link apologized, but said there was nothing he could do. He advised Ed to consult with his veterinarian and sent him home. And there things might have stood—if not for a crazy German graduate student in the lab.

After Carlson left, the crazy German started splashing his hands right in the pail of blood. Given the cold outside, and how long it had been exposed to the air, that blood should have been clotted and thick. But it wasn’t. It was still runny.

“Mein Gott! Dere’s no clot in dis blut!”, the German shouted. <SPLASHES> Then he wheeled on Link, enraged. How could he send that poor man home in a blizzard?

“Vat vill he find ven he gets home? Sicker cows. And ven he and his good voman go to church tomorrow und pray und pray und pray—vat vill dey haff on Monday? More—dead—cows!”

Link felt ashamed. The German was right—he had to help. Link started working that night, and basically didn’t stop for two decades.

Link had a long, horsey face with slicked-back amber waves of hair. He often purposely dressed like a country bumpkin, with a pipe and homemade sweaters and straw hats. Sometimes even a cape. He looked like a Hee Haw extra.

But he was a sharp scientist. And however dramatic the pail of blood was, he realized that the key to the dead cow was the feed the farmer had brought. The sweet clover.

All over the Great Plains, farmers then were losing cows to routine operations like dehornings and castrations. Other cattle died even without surgery. Over a few weeks, huge pockets of blood would erupt on their flanks—mounds of fluid a foot wide. After a month or two, they died of internal hemorrhages.

Scientists at first suspected a disease outbreak. But the cows had no fevers or other signs of infection. The only common factor was sweet clover. All the dying cows had been eating it.

Sweet clover is a grass with a distinct smell when it’s cut—like freshly mowed hay. Cows love it. But if farmers didn’t dry it properly, it got moldy.

In normal times, they would have thrown the moldy clover away. But during the pinch of the Great Depression, they couldn’t afford to. They fed cows the spoiled clover anyway. It was a death sentence: thousands upon thousands collapsed. Ed Carlson was far from alone in facing ruin.

But why did moldy clover cause hemorrhages? There had to be some chemical responsible. That’s what Karl Link set out to find.

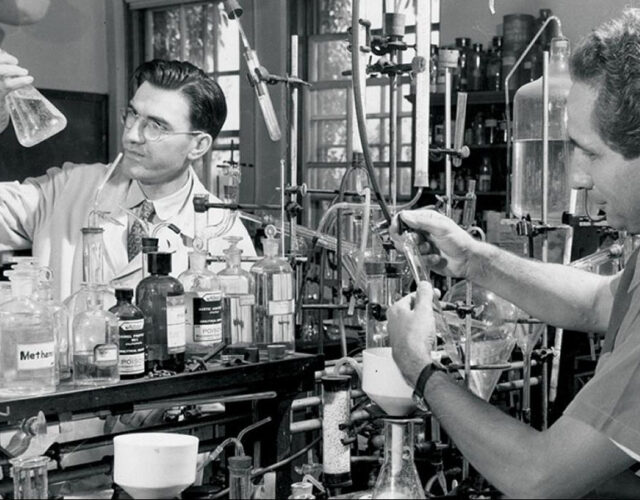

To investigate the mystery, he and his team mashed up huge mounds of moldy clover, then used various test-tube tricks to extract different chemicals. There were hundreds of extracts to examine. Each one got purified and injected into rabbits, to see whether it caused hemorrhages.

Frankly, this is the unsexy side of science. Month after month of tedious labor—most of it futile. For six long years, there was nothing but false starts and dead ends.

Still, science has its moments. At long last, in June 1939, a graduate student named Harold Campbell stayed up alone all night working—and finally isolated six tiny milligrams of a chemical that caused massive hemorrhages in rabbits. They’d finally found the poison.

Link arrived at work the next morning to find Campbell snoring on the lab’s couch, having crashed asleep. Meanwhile, a local farmhand was watching over the lab.

Now, Link knew the farmhand liked to have himself a nip of alky-hol at work—probably stolen from the lab supplies. But Link was startled to see the man openly drinking booze that morning. “I’m celebrating, Doc!,” he cried. “Campy has hit the jackpot.”

Link could only shake his head and laugh. They had indeed hit the jackpot.

So what was this poison? Again, sweet clover smells like freshly cut hay. And coincidently, the molecule that causes the hay smell was closely related to the molecule Campbell isolated.

The hay-scent molecule is called coumarin [“KOO-mur-inn”]. Mold takes this coumarin and tweaks it chemically. In short, it fuses two coumarin molecules together to form dicoumarol [“die-KOO-mur-all”]—which is bad, bad news.

Whenever cows or other mammals ingest dicoumarol, it blocks a certain enzyme. That enzyme in turn activates the nutrient vitamin K. Without active vitamin K, blood cannot clot. So long story short, dicoumarol prevents vitamin K from entering the blood. Hemorrhages erupt, and even mild wounds gush blood.

Still, as they say—the dose makes the poison. Dicoumarol killed by thinning the blood and preventing it from clotting. But preventing clotting isn’t always a bad thing. In fact, clots often cause strokes and heart attacks, and people who suffer strokes and heart attacks often take blood-thinners.

And here, in dicoumarol, was the most potent blood-thinner anyone had ever seen. Karl Link had set out to find a poison. But he realized that, maybe, in minuscule amounts, this poison could save lives.

Unfortunately, lab tests revealed that dicoumarol had flaws as a blood-thinner. It took too long to work in test animals, and it was hard to get the dose right. The line between busting up clots and causing massive hemorrhages was too thin for comfort.

So, Link and his team started investigating some chemical cousins of dicoumarol. They’d tweak the molecule by swapping some atoms around, then test whether the new molecule worked better. But again, it was long, tedious labor spread over several years, with a hundred-plus variations to try.

All in all, it seemed like a good idea that just wouldn’t pan out. And there things might have stood—if not for a disastrous camping trip.

In fall 1945, after a decade of work on blood-thinners, Karl Link needed a vacation. <PADDLING> He went canoeing in the forests of Wisconsin. He could not have picked a lovelier place—or a worse week. <THUNDERSTORM> As soon he dipped oar into water, the heavens opened up. It rained, and rained, and rained some more, leaving him cold and miserable.

Link soon developed a hacking cough. And his doctor confirmed the worst. An old case of tuberculosis had flared up. Link’s one-week camping trip turned into six months enforced vacation at a sanatorium.

There Link sat, week after week, resting. For pep, he got a shot of cod-liver oil each day. Plus—this being Wisconsin—three bottles of beer.

Still, he was bored—deathly bored. So bored that one day he started flipping through a Reader’s Digest article on, of all things, the history of rat control. Why not? There was nothing else to do.

But as Louis Pasteur said, chance favors the prepared mind. After years of obsessing over blood thinners, the article sparked an idea.

The problem with typical rat control is that most poisons taste horribly bitter. Rats won’t do more than nibble them. Poisons also cause stabbing stomach pain. And rats aren’t dumb. If something hurts them once, they never eat it again.

But Link knew that dicoumarol was not a typical poison. It apparently had no taste: animals didn’t shy away from it during tests. Equally important, it poisoned you only gradually. Cows consumed it for weeks before any trouble started. So rats seemed likely to keep eating it and eating it, until too much built up inside them.

Once Link got out of the sanatorium, he started testing dicoumarol on rats. It turned out that dicoumarol worked too slowly in rodents. Just a biochemical quirk of theirs. So his team started testing its chemical cousins, the molecules they’d tweaked. The most potent of all was number 42. It proved a heck of a rodenticide. A product finally hit the shelves in 1948, called warfarin.

And wow did it kill rats. Heaps and heaps and heaps of them. The biggest rat-buster in history.

Now, rat control wasn’t exactly Nobel-Prize worthy, but it was sure useful. Warfarin turned into a multimillion-dollar business, too, making Link proud. And again, there things might have stood, with a perfectly adequate invention—if not for a suicide attempt in Philadelphia.

The suicide attempt involved a soldier. He got drafted into the army in 1951, destined for Korea. And for whatever reason he simply couldn’t face it. So, he decided to kill himself. He went to the hardware store and asked for rat poison. The clerk handed him a carton of warfarin.

That night he sat down and ate a teaspoon. The warfarin had been mixed with cornstarch, so it tasted sweet, like a marshmallow. <SWALLOW> Then he laid down on his bed to die.

Except, he didn’t die. To his frustration, he woke up in the morning. So the next night he sat down and took more warfarin <SWALLOW> then laid down to die. Once again, he woke up alive. He couldn’t even kill himself right.

This happened several more times. Six times he tried killing himself—and six times woke up in the morning, crushed. Pretty soon, he’d finished the whole carton of rat poison.

But while he didn’t die, he didn’t feel good, either. His kidneys ached, and stomach cramps left him doubled over in agony. Most scary of all, he got nosebleeds—real gushers. It’s one thing to die in your sleep, quite another to watch yourself bleed to death.

At some point, he apparently changed his mind about dying. He checked himself into a military hospital near Philadelphia instead.

To their shock, the doctors there realized he had “sweet clover disease”—the same thing that killed Ed Carlson’s cows. By then, scientists knew that afflicted cows would buck up after shots of vitamin K. So the doctors injected the soldier.

It worked. Remarkably quickly, he recovered. In fact, that was the most amazing thing about the whole case—how uneventful his recovery was. He’d eaten a carton of rat poison—and walked away fine.

Well, word about this case got back to Karl Link in Wisconsin. He was shocked—but also intrigued. How had the soldier survived the most potent rat poison in their arsenal?

Link’s team ran some more animal tests. And they discovered that rodents were far more susceptible to warfarin than other animals. Again, it’s a biochemical quirk of theirs.

This revived their hopes of finding a blood-thinner drug for humans. In fact, more tests revealed that warfarin didn’t have the same shortcomings as the first compounds they’d tried as human drugs. It thinned the blood relatively quickly, and was more forgiving about the dose. Best of all, vitamin K reversed it—an immediate antidote. All in all, warfarin was a damn fine blood-thinner.

Still, it was also rat poison. Good luck convincing doctors to prescribe it. It seemed like a dead-end. And yet again, there things might have stood—if history had not dealt another wild card.

In September 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower was visiting his wife’s family in Denver when he suffered a heart attack. He was rushed to a military hospital. Eisenhower lived, but needed blood thinners to prevent a probable second heart attack.

And who knows why. Maybe the doctors in Denver had heard about the Philadelphia soldier-suicide case through the military grapevine. Regardless, the cardiologist on hand gave the President warfarin.

It worked brilliantly. Eisenhower popped back quickly, and the press ran glowing stories about the miracle drug that saved the president. Rat poison or not, prescriptions boomed.

Now, warfarin isn’t the only unlikely drug in history. Others have been derived from snake venom and poison-tipped arrows from the Amazon. I’ve actually got a bonus episode about these poison-drugs at Patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

Which reminds me, this story idea came from Patreon listener Katherine in Washington. You too can submit your own story ideas through Patreon as well, and listen to tons of bonus material, too.

But amid all the crazy venoms and poisons we now use as drugs, warfarin has to be the most unlikely. It came from moldy clover, killed thousands of cows, then took a detour as a rat poison.

Today, though, two million people take warfarin every year in the United States alone. It now appears on the World Health Organization’s official list of “essential medicines.” Few drugs have ever done more good.

Sadly, farmer Ed Carlson never did save his cows. But in facing down that blizzard, and finding Karl Link, he helped save more lives than he ever could have imagined. True, Ed didn’t have much faith in science—but the thing is, science works whether you believe in it or not.