On this episode of The Disappearing Spoon, Sam Kean talks about a murder mystery that rocked Boston in 1849. Harvard University alum and physician George Parkman had gone missing. The last place he was seen alive was at the Harvard medical building, which had plenty of bodies, but police couldn’t find Parkman’s there. That is until a janitor intervened and implicated a medical school professor. The ensuing murder trial was a media circus equivalent to the O. J. Simpson trial. And just like that trial, it also familiarized the layperson with forensic and anatomical sciences.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Photo: Wellcome Collection

Transcript

It was the turkey that first got the janitor thinking murder.

On Thanksgiving day in 1849, he had a succulent bird sitting on his kitchen table. Yet here he was, hacking at the brick wall of a latrine in Harvard Medical School with a hatchet. He wanted to be at home, feasting. But he couldn’t eat with all those clues nipping at his conscience. A Harvard grandee had gone missing, and the janitor thought he knew where.

Unfortunately, there were five layers of brick to the vault, and a hatchet just wasn’t the right tool. So the janitor quit after ninety minutes, cold and hungry. The next morning he dropped by a local foundry to borrow a hammer, a better chisel, and a crowbar—to start work on a new water main, he claimed. Then it was down into the vault again.

Several hours later he finally opened a hole in the innermost layer of brick. He held his lantern up, peering into the darkness. But a draft kicked up and almost snuffed the flame. You can imagine the odors bursting forth as well.

Still, he widened the hole and tried again, shielding the lantern as he reached it inside. It was a moment right out of Edgar Allan Poe. He saw mostly the nasty things you’d expect in a latrine. But as his eyes adjusted to the gloom, he noticed one additional thing. In the center of the pit, glowing a dull white, sat a human pelvis.

The only question was—whose was it? After all, this was a medical school. There were corpses everywhere. So was it the missing Harvard grandee? Or the body of someone else that had met an equally wicked end?

The janitor was hardly alone in obsessing over the missing Harvard grandee; people in Cambridge, Massachusetts, talked about little else that November.

Dr. George Parkman—60 years old, tall, impossibly skinny—had stopped by a grocery store one Friday afternoon to purchase sugar and butter. He also asked the grocer to hold onto a treat for his invalid daughter: a head of lettuce, a delicacy in November. Parkman told the grocer he had an appointment to keep, and would be back in a minute. He never returned.

Parkman was a Harvard alum, and a fabulously wealthy real estate mogul; he actually donated the land on which Harvard’s squat, three-story medical building sat. Less nobly, Parkman owned several tenement slums and was a stickler about rent. He also made a killing as a loan shark, hounding his debtors for every cent—especially if they’d crossed him.

And Dr. John White Webster had crossed him. Webster, age 56, was something of a hellion. He’d graduated from Harvard Med and did a residency in London, where he’d loved to attend public executions.

Eventually Webster ended up teaching chemistry at Harvard Med; his lab sat in the medical building’s basement. His lectures often featured explosive pyrotechnics, and he loved whipping up laughing gas to get students high.

But if Webster had given up working as a doctor, he was still addicted to the doctor lifestyle. The typical Harvard professor then was independently wealthy and worth $75,000, or $2.3 million today. Some professors’ mansions were so lavish that they appeared on local tourist maps, so people could walk by and gawk.

In comparison, Webster’s salary was just $1,200, less than $40,000 today. But Webster tried to keep up a doctor’s lifestyle, buying a six-bedroom house and entertaining lavishly with oysters and wine. Before long, he and his family had run through all his savings. He was soon bouncing a $9 check.

Rather than economize, Webster approached George Parkman for several loans. It was a bad idea. He had no financial discipline, and finally had to mortgage a beloved collection of minerals and gems to Parkman as collateral. People around town began whispering about Webster’s debts, which infuriated him.

And by the fall of 1849, Parkman was pestering Webster for his money back. The sheriff even threatened to repossess Webster’s furniture. Webster grew desperate to buy time. So he went behind Parkman’s back and mortgaged his beloved mineral collection to two other creditors.

Unfortunately, one of those creditors was Parkman’s brother-in-law, who informed Parkman of the double-dealing. The news made Parkman livid, and he eventually confronted Webster in the basement of the medical school.

Pay me or else, he demanded. Both men lost their tempers, and the building’s janitor overheard them screaming. Webster finally promised to scrape together $483 and have it ready the Friday before Thanksgiving.

When that Friday came, Parkman made arrangements with the grocer about the butter and sugar and lettuce, and marched over to collect from Webster. Webster later told the police that Parkman snatched up the $483 without a word and hurried off.

That’s when the mystery started. No one ever saw him again.

Parkman was pretty OCD in his habits, so when he didn’t turn up for dinner that night, his family began to fret—then panic. Parkman had a bad habit of carrying too much cash around after collecting debts. He’d been mugged for it before and no doubt had been again, with fatal results.

The police started dragging the nearby Charles River. They also roughed up some local hoodlums for information. Nothing solid turned up. The last confirmed sighting of George Parkman was at the Harvard medical building. Indeed, there were rumors going around that Parkman’s dog—who accompanied him on debt-collecting rounds—had been seen lingering near the building, as if waiting for his master to emerge.

So a few days before Thanksgiving, the police made their way to the medical school to poke around. First they searched the apartment of the most probable suspect—the lowly janitor who lived in the basement. Nothing turned up.

So with great reluctance, the police went to the room next door and knocked at Webster’s office. A magnanimous Webster said he understood and watched as they searched his lab. Or at least most of it. No one was brave enough to pick through his private latrine.

They also found a locked closet, and when one cop asked what was inside, Webster explained that he kept explosive chemicals there. That ended that, and the police bade the professor goodbye and returned to roughing up lowlifes.

Little did the police know, the man who would soon break the case wide open had been right under their noses the whole time.

The medical school janitor, Ephraim Littlefield, had a chinstrap beard and high part in his hair; he looked like a gentle Quaker. But he was also wrapped up in the dirty business of robbing graves to get bodies for Harvard’s anatomy classes.

Because Littlefield and his wife lived in an apartment in the medical building’s basement, he could meet grave-robbers carrying dead bodies at all hours. And Littlefield wasn’t above a little side action, either. After a local doctor botched an abortion once, and killed both the mother and the fetus, Littlefield got caught asking for $5 to secretly dispose of the two corpses.

This dark commerce made the janitor a prime suspect in Parkman’s disappearance—and the police had indeed searched Littlefield’s apartment first in the medical building. So, perhaps fearing he’d be accused, Littlefield began his own investigation over the next few days, by following several nagging clues about Dr. Webster.

Littlefield’s basement apartment was located next door to Webster’s lab, and Littlefield was used to entering and leaving the lab at will to stoke fires and tidy up. Suddenly, though, after Parkman disappeared, Webster began locking the lab door. Yet the furnace inside was still blazing—so hot that Littlefield couldn’t even touch the wall on the other side without burning his hand.

Even stranger was the turkey. Webster mostly ignored Littlefield as the help, and the professor was known to be in debt. Yet a few days before Thanksgiving he’d treated the janitor to a succulent eight-pound bird. Why? And why had he made Littlefield trek across town to pick it up, instead of having it delivered? Was he getting Littlefield out of the way?

Suspicious, Littlefield began poking around. One day he slipped through an open window into Webster’s lab, but a hasty search found nothing amiss.

That’s when he decided to dig. On Thanksgiving Day, Littlefield found the medical building deserted. So while his eight-pound turkey grew cold, he grabbed a hatchet and chisel, posted his wife as a lookout, and crept into the vault beneath the basement to hack through the brick wall of the privy there. The police had declined to search the professor’s latrine. The janitor wasn’t so squeamish. And when that glistening white pelvis turned up the next day, he ran immediately to fetch the police.

After this, the police finally did a thorough search of Webster’s lab. They found bones and dentures in Webster’s furnace, as well as shanks of leg in the latrine.

Most gruesome of all, one cop began digging through Webster’s tea chest—where he kept his beloved mineral collection, the source of all this trouble. Near the bottom, the cop felt something squishy and decidedly un-rocklike. It was a gutted-out ribcage, with a thigh jammed inside like a human turducken.

The public was stunned. A murder—at Harvard? As one newspaper put it, “In the streets, in the marketplace, at every turn, men greet each other with pale, eager looks, and the inquiry, ‘Can it be true?’”

But if many people were ready to hang Webster, local prosecutors looked at the evidence and swallowed hard. Making a case would not be easy. There was a body, sure, but it was headless. Was this even Parkman? After all, corpses were shuttled in and out of the medical building all the time.

And if it was Parkman, perhaps someone had killed him elsewhere—or even found him after a natural death and sold the body to the school.

The police couldn’t discount Littlefield, either. After all, who’d found the body? How had he known exactly where to look? And everyone remembered his willingness to dispose of a dead mother and fetus for five lousy bucks. Perhaps he’d anticipated a reward for Parkman’s body, or was in cahoots with some grave-robbers. Any way you sliced it, there was reasonable doubt everywhere.

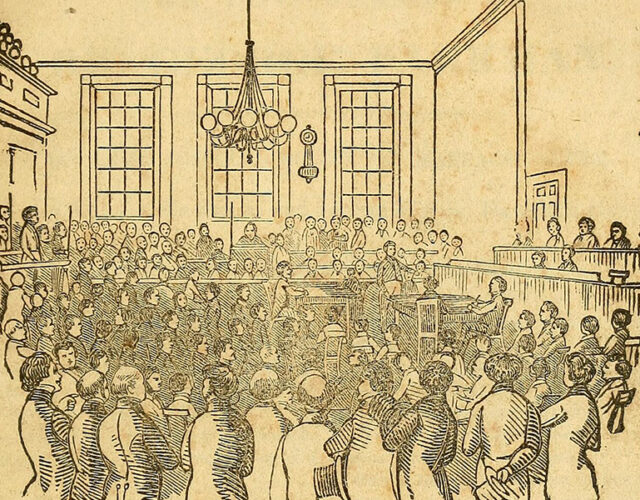

Given the juiciness of the scandal, Webster’s trial in March 1850 was probably the biggest court case in American history to that point. Officials actually built cattle chutes to herd spectators in and out of the courtroom; sixty thousand people tromped through over eleven days.

The case also exposed fault lines of class and caste within the Boston area. Hardscrabble Bostonians blasted Webster as a psychopath and demanded that he swing. Haughty Cambridgians, meanwhile, sneered at Littlefield as a slimy sneak who’d obviously framed his boss.

The presiding justice at the trial was novelist Herman Melville’s father-in-law. The judge also sat on Harvard’s board of overseers, which normally would have been a conflict of interest—except that both the defendant and murder victim were also Harvard alums. As were the lead lawyers for both sides, plus twenty-five of the witnesses. It was half trial, half reunion.

Webster’s defense was simple. I’m a Harvard man, and Littlefield’s not. So between the two of us, he obviously did it. A bit more materially, Webster’s lawyers pointed out that the state had no murder weapon and no idea how Parkman died. Could the jury really convict a man with no weapon and no visible wound on the corpse? Especially in a building full of corpses?

Still, the prosecution had one big thing going for it. The body had been found in a medical school, steps away from some of the world’s foremost authorities on anatomy. They were experts at reading the human body, and while they respected Webster as a colleague, the corpse in his latrine told a damning tale.

First of all, the anatomists proved the body was Parkman’s. Several of them had known Parkman for years, and their practiced eyes recognized the gaunt torso discovered in the tea chest. Similarly, Parkman’s dentist—another Harvard fellow—recognized Parkman’s scorched false teeth from the furnace, since he’d crafted the teeth himself.

In fact, the dentist could tell that the teeth had been cooked inside a human head. If false teeth are cooked in a furnace by themselves, he noted, they heat up quickly and pop like popcorn. These teeth hadn’t popped, implying they’d been shielded from the heat by something moist, like human flesh. It was a virtuoso display of forensic dentistry.

As for who killed Parkman, the clues pointed to Webster. Whoever had carved up the body had betrayed an expert hand in separating the sternum, ribcage, and collarbone. Given the thick muscles and tendons in the chest, it’s difficult to disengage the sternum without cracking it; only someone with practice dissecting bodies would know where to cut. The ex-doctor Webster fit that description, while Littlefield the janitor had never wielded a scalpel.

Still, despite all the evidence against Webster everyone knew that he’d get off, given the pro-Cambridge jury. The trial ended just before 8pm on a Saturday, and the jury returned three hours later with the verdict. Melville’s father-in-law hushed the courtroom and asked them how they found the defendant.

Webster had remained aloof throughout the proceedings, betraying no emotion. But when the verdict of guilty rang out, he “started as if shot” with a gun, said one witness. Then he slumped backward into his chair, stunned. A few yards behind him, Ephraim Littlefield broke down weeping.

Because of all the publicity surrounding it, Webster’s trial provided a huge boost for forensic science in the United States, much like the O.J. Simpson trial familiarized laypeople with DNA evidence 150 later.

Equally important, the trial helped rehabilitate the reputation of anatomical science. To find bodies to dissect, anatomists had long been robbing the graves of the poor, and the poor therefore despised them.

But in this case, the anatomists had condemned the elite professor and exonerated the poor janitor. One observer, in fact, called the trial the fairest in American history: “There was never seen a more striking instance of equal and exact justice[:] money, influential friends, able counsel, prayers, petitions, the prestige of a scientific reputation, [all] failed to save him.”

And make no mistake, Webster did kill Parkman: he finally confessed to this a few days before he was scheduled to hang. Webster said that, during their final, fatal meeting, Parkman had called him some dastardly names and threatened to get him fired—the last step toward financial ruin.

So in a fit of rage Webster had snatched a nearby log and smashed Parkman’s temple in. Parkman crumpled, and a panicked Webster dismembered the body and started burning it.

The confession, it turned out, was a last-ditch plea for clemency. As Webster told the governor’s office, he’d committed manslaughter, not premeditated murder, and therefore deserved jail time, not death. The governor was unmoved, and John White Webster was hanged a few days later.

The case lived on a long time in people’s imaginations, even outside of Boston. When Charles Dickens visited America in 1869, the one place he wanted to see in Boston was the Parkman murder scene—to the embarrassment of locals. Similarly, when Mark Twain visited the Azores in 1861, he was tickled to meet two of Webster daughters, who’d no doubt moved there to escape notoriety.

As for Ephraim Littlefield, it was less that he couldn’t forget the case and more that people wouldn’t let him forget it. Souvenir-seekers, recalling the trial, used to run up to Littlefield in the street and yank strands of his hair out. More happily, Littlefield collected a $3,000 reward from Parkman’s family for helping collar the murderer. After that, he never had to worry again about where his Thanksgiving turkey would come from.