It’s not quite as far-fetched as it’s sometimes made out to be, but “foreign accent syndrome” is a real, frightening, and bizarre neurological disorder.

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

The pain felt like an ax to the skull. A moment later, Helen crumpled to her knees, unable to move.

It was a rainy Monday in Indianapolis. Helen, a 47-year-old graphic designer, had been feeling odd all day. Her lips and tongue felt numb, as if she’d gotten a shot of Novocain at the dentist.

Then, late that night, she was doing dishes when something snapped—an ax of pain at the base of her skull. After collapsing, she crawled upstairs to bed and woke her husband. Ultimately, though, she decided to sleep the pain off.

She awoke in the morning with an excruciating headache. And the numbness had spread from her face to her right arm. She went straight to the emergency room. A long, frustrating day of tests followed. The doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong.

Helen returned home that afternoon and crashed asleep. Her husband brought her dinner a few hours later, but she didn’t stir. She slept for 16 hours.

Her husband had to work the next morning, so Helen woke up alone in the house. The numbness and pain persisted, but she dragged herself to the bathroom. On the way, she muttered something to her Jack Russell terrier. Something like, “Hey, girl. Ready to go downstairs?”

But the voice that emerged from Helen mouth—it wasn’t hers. It sounded bizarre, alien, as if she had an accent.

Still foggy, Helen staggered to a mirror and spoke again. Just to confirm that, yes, the strange voice was coming from her own mouth.

Frightened, she kept talking to herself, trying to fix the problem. She tried muttering, “I sound weird.” Except it came out, “I sound word.”

Thinking she could swap in another word, she said to herself, “I’ll just try something different.” But that came out bizarre, too. It sounded French: “I’ll just try something dee-fah-rawnt.” So she tried another remark: “That’s strange.” But again, it sounded French: “That’s strahnge.”

Helen broke down crying—something was desperately wrong. She’d been born and raised in Indiana. She’d spoken with a flat Midwestern inflection her whole life. But now, somehow, she’d acquired a foreign accent.

After some online research, Helen—whose name I’ve changed for privacy’s sake—realized that she’d developed a rare neurological disorder called foreign accent syndrome, or FAS. FAS is usually caused by mild strokes. And Helen’s FAS left her with several linguistic quirks.

For instance, she has trouble pronouncing the letters t-h: mother and father become mudder and fadder. She also chops up words in unusual ways: “I call-ed my doc-tore,” or “I’m quite com-for-tah-bul.” Overall, Helen describes her accent as “a blend of French, Dutch, and German” with some South African and Caribbean English mixed in. Definitely not her Indiana voice.

Language is very closely tied to our sense of self and sense of belonging to a community. Voices are part of our identity. So foreign accent syndrome can be devastating.

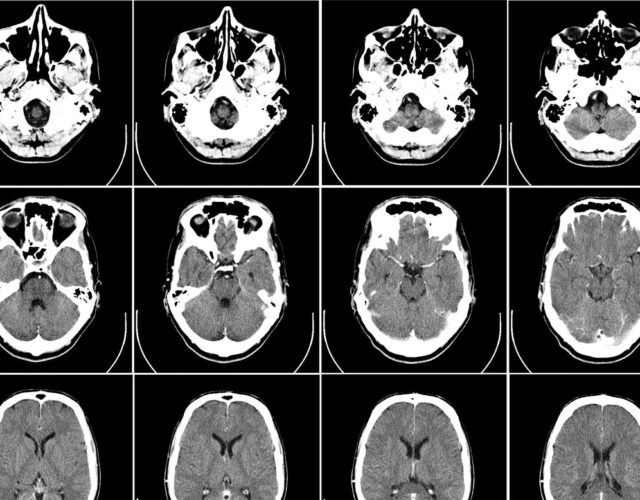

In many ways, Helen is a typical FAS patient. The average age of onset is 48. For some reason it’s more common among women. Also, during her initial incident, Helen felt numbness on her right side, which is controlled by the brain’s left hemisphere. The brain’s left hemisphere dominates certain aspects of language production. Left hemisphere damage can therefore disrupt language.

Beyond the accent, FAS can affect other aspects of speech, too. Vowels sometimes shift: “ship” becomes “sheep.” Sometimes people pronounce silent letters or add unnecessary syllables reminiscent of Pig Latin: “Standing” becomes “suh-tanding.” Or “picture” becomes “pik-uh-ture.”

The rhythm and melody of speech, the prosody, can also change. People’s pitch might rise where you’d expect it to fall, or vice-versa. Or they might stress the wrong sill-AH-bulls in words. Sometimes people pause too often, as if struggling—to come up—with the next word.

For the most part, people with FAS can still make themselves understood and still express complex ideas; their intelligence doesn’t suffer.

It’s also important to note that patients typically cannot speak the language associated with their accents. Helen’s accent is regularly mistaken for French or German, but she doesn’t parlez-vous, and she doesn’t sprechen sie.

In fact, the new accent that emerges doesn’t match any one accent at all—it’s more a hodgepodge accent. It might have vowels you’d hear from native French speakers, rhythms associated with Italian, pitches reminiscent of Chinese, and so on. For those reasons, FAS speech isn’t a true accent, but it contains enough quirks and distortions that our brains classify it as somehow foreign.

But the thing is, different people often interpret the same FAS accent in different ways. It sounds German to one person, Russian or French to another. The listeners’ background actually influences what they perceive. The accent is in the ear of the beholder.

I should also clear up one common misconception. Sometimes stories circulate in supermarket tabloids of people having a stroke or something and waking up with the ability to speak a whole new language—a language they never spoke before.

Sadly, however cool that would be, those stories are hogwash. I don’t care if your best friend’s sister’s boyfriend’s brother’s girlfriend heard from this nurse who knows a doctor who swore it happened to this guy he knows. People just don’t wake up speaking new languages. Instead, it’s probably a case of foreign accent syndrome that got exaggerated through a game of telephone.

Now, beyond knowing that it arises after mild brain damage, scientists disagree about what causes foreign accent syndromes. It’s also possible that different cases have different causes. But the root of most cases lies in the mouth and throat.

Speaking a word aloud requires two steps, planning and execution. Planning takes place in the brain. Execution involves moving the lips, tongue, voice box, and lungs in a coordinated way.

Speech problems in general can arise from problems either step, but foreign-accent syndrome seems to be an execution problem. Scientists know this because people with language-planning problems often make characteristic mistakes. Like saying “dappy hays” instead of “happy days.” But FAS patients never made those oral typos.

More specifically, some scientists trace the execution problems of FAS to poor articulation. Speaking aloud requires shaping the mouth and throat just so, to sculpt the flow of air streaming through. Those movements are delicate, and brain damage can hinder our ability to choreograph them. If the mouth or throat is shaped wrong, the speech that emerges will sound distorted.

Again, strokes are the most common trigger for FAS, but scientists have linked it to other things, too—multiple sclerosis, infections, electrocution, schizophrenia, brain tumors, even neurotoxicity from spider bites.

And FAS doesn’t just appear in English. FAS appears in languages worldwide and can cause a dizzying array of perceived accent shifts: from Japanese to Korean, Spanish to Hungarian, Dutch to Turkish, Georgian to Cajun, and so on.

But according to one survey of cases, most FAS patients start off speaking languages like English or Dutch and acquire accents associated with Romance, Eastern European, or tonal languages like Chinese.

Why? The researchers who did the survey argue that Romance, Eastern European, and tonal languages require more effort to speak. The throat and lungs have to work harder, due to the language’s pace or extra qualities like tones.

If someone suffers an injury that affects their articulation, they might compensate—consciously or not—by forcing their vocal apparatus to work harder. This would then cause listeners to perceive an accent from one of those more effortful languages.

Now, not all scientists buy the idea that certain languages take more work to speak. But if that theory does prove true, it would mean it’s much more likely for a native English speaker to acquire a faux French or Chinese accent than for the inverse to happen.

Although the first reported case of foreign accent syndrome dates back to 1907, there’s been much more interest in the syndrome recently. 93 percent of all known cases have appeared in the neurological literature since 2000.

That increased awareness has its pros and cons. With increased awareness, patients today are more likely to get a diagnosis and find support. That’s a comfort.

That said, there are downsides, too.

The downsides of increased attention on FAS are many. Whenever Helen, the woman the start of the episode, had a doctor’s appointment, eight or ten neurologists would crowd her, all barking questions, eager to get a glimpse of a real-life FAS patient.

Media attention can be overwhelming, too. That’s especially true when people with FAS are asked to do such silly or demeaning things, like pose for photographs holding a mini Eiffel Tower. It makes people feel freakish.

Sadly, the odds of recovering from FAS are not great. The accents usually embarrass people, and they work hard to fix it. They’ll listen to old recordings of their speech and try to imitate themselves. Many also seek speech therapy. Nevertheless, despite all the work, less than half of patients recover their original accent.

Those mediocre odds leave many FAS patients struggling to cope. To be sure, some find a silver lining. One normally shy woman reported that the new accent helped in social situations: It was a natural ice-breaker and made for an obvious topic of conversation.

People with FAS often chuckle over people’s faux pas as well. Sometimes strangers rush up and start speaking French or German, eager to test their foreign language skills on a supposed “native.” Helen also said that people never could tell her apart from her sisters on the phone. But now, she laughs, they know it’s her instantly.

More commonly, however, people feel angry and frustrated. Helen remembers a friend calling her up shortly after her foreign accent emerged. The friend hung up immediately upon hearing her voice, thinking she’d dialed a wrong number. When the friend called again, Helen had to prove her identity by talking about common memories. Helen’s mother-in-law also more or less ordered her to snap out of it. She insisted that if Helen slowed down and took her time, she could speak correctly if she wanted to.

Fortunately, Helen still has a good relationship with her mother-in-law. But not all patients are as lucky with their loved ones. One patient lamented how people would whisper that he had taken to drinking. Other patients have been labeled “mentally unstable” or accused of perpetrating a “sick joke.”

In some cases, people grieve for their voices and listen to old recordings of their voice over and over. Some people feel like a twin has died, or that even their old self died. One woman whom Helen knows can’t pronounce her own name: “Tina” comes out Tee-anna. Even pets sometimes look askance at their owners and don’t know how to react. Imagine your own pet shying away from you.

People face discrimination as well. Perhaps the most famous case of foreign accent syndrome involved a 28-year-old Norwegian woman. When Nazi Germany bombed Norway in 1941, she got beaned in the skull with shrapnel. She fell unconscious for several days and suffered mild brain damage.

When she woke up and started speaking, her pitch was off. Pitch helps determine a word’s meaning in Norwegian. And her sudden clumsiness with pitch made her accent sound uncannily German—the language of the enemy. As a result, shopkeepers accused of her being a Nazi. Some refused to sell her food or clothes.

Some modern FAS patients cope with the stigma of being labeled a “foreigner” by shopping at places where they don’t have to interact with people. Others go to extreme measures to find a new community. One British woman flew to Poland because she believed that people there shared her accent and that she’d feel at home again. An American woman traveled to England for similar reasons—only to find everyone there assumed she was South African. The American woman also had trouble with immigration officials, who questioned the supposed discrepancy between her speech and her passport.

People with FAS also cope by censoring what they say. Helen says she’s learned the hard way to avoid certain words. One day, she was teaching a course for children on how to train dogs. She told one mother that her child needed to fill out some sheets. Only “sheets” came out s-h-i-t-s. Luckily, the mother didn’t overreact, but Helen now uses the word forms instead.

But not every word has an easy workaround. From the very beginning, Helen could not say the word yesterday. The t always goes missing. Yesserday. She’s been searching for a dozen years to find a short workaround for yesserday and still hasn’t come up with one.

As a result of such mistakes, instead of speaking normally, Helen is constantly monitoring her own speech to avoid certain words. But being constantly self-aware like that is exhausting. She compares her mental state to learning a foreign language; she has to think consciously about every word and is always second-guessing herself. Holding even simple conversations has become a slog.

Helen finds solace in running FAS support groups online, and by checking in with people who sound down or depressed. She herself remains upbeat and can laugh at herself most of the time. But there are sad days, too.

We often forget how powerful voices are. They form a key part of our identities. And perhaps more than any other trait, they bond us to our communities. Our voices declare, I’m one of you; I belong.

But Helen and others with FAS know how fragile those bonds are. As she says, “My husband doesn’t get to hear the voice that said ‘I do.’ My child doesn’t get to hear a bedtime story because I can’t say [certain] word[s] in ‘Little Red Riding Hood.’”

Like so many things in life, we take our speech, our voices, for granted—right up until the moment they disappear, and take our old selves with them.