Many people may know the mystery surrounding the lost colony of Roanoke Island, but few may be familiar with the scientist behind the misadventure. Thomas Harriot is to blame—and not just for that, but also for the spread of a devastating public-health epidemic.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

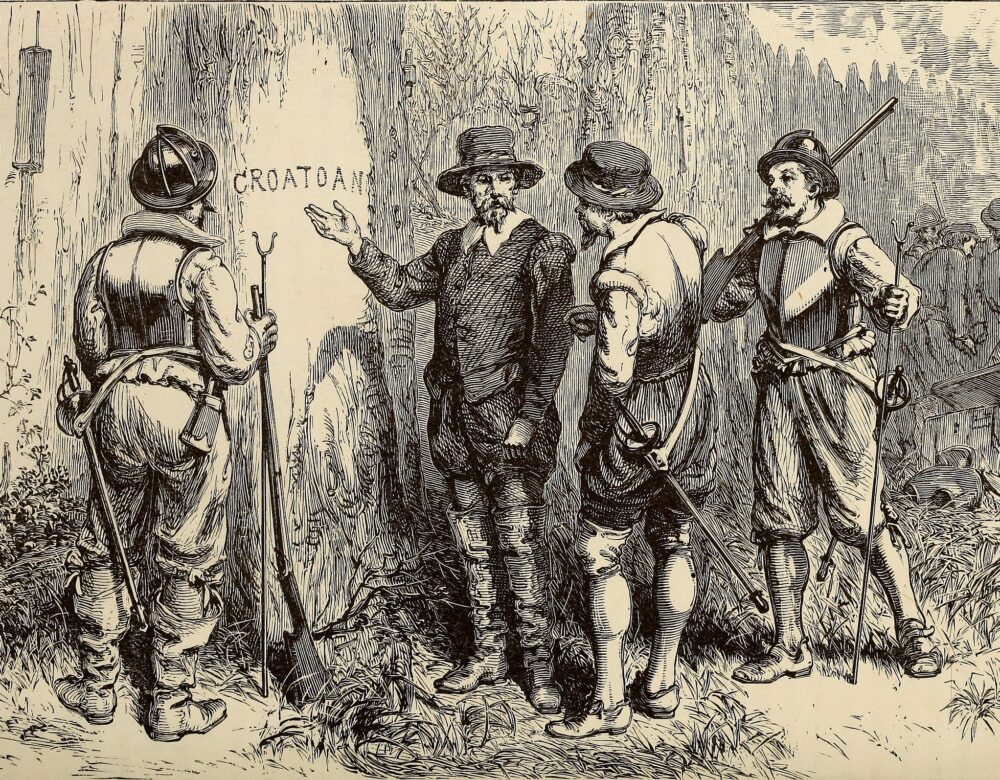

It’s one of the biggest mysteries in American history. In 1590, an English sailor stepped ashore on Roanoke Island, off North Carolina. Just a few years earlier, a colony had been founded there to give the English a foothold in North America. But that day, the sailor found not a single living soul. Every single person had vanished without a trace.

And to this day, their fate remains a mystery. Oceans of ink have been spilled debating what happened to them. But no one can say for sure.

Now, rather than add my own fruitless conjectures, today I’m going to focus on something else—an overlooked angle of the saga. Namely, the man to blame for the whole misadventure. A scientist named Thomas Harriot.

Harriot had a thin, stern face with a pointy red goatee. In the most famous picture of him, he’s wearing a frilly Elizabethan collar. It looks like he doesn’t even know what the word “smile” means.

Beyond helping to launch the doomed Roanoke colony, Harriot’s scientific work in North America altered the course of history in profound, and frankly disastrous ways. For one thing, he spawned a public-health epidemic that killed well over a hundred million people.

For better or worse, Harriot also helped propel England to the pinnacle of world power. In Harriot’s youth, England was a rude backwater—a laughingstock in Europe. But his work erased that perception, and transformed this laughingstock into the dominant colonial power of the next several centuries. He’s one of the most influential people you’ve never heard of.

As the son of a blacksmith, Thomas Harriot received little schooling as a child in the 1560s. He nevertheless proved a prodigy in math and science, and enrolled at Oxford University at age 17.

Over the next several decades, he did pioneering work in several technical fields. He developed an early theory of wave refraction. He established that snowflakes were six-sided, and invented the greater-than and less-than signs in math. He greatly advanced our understanding of compound interest and the binary, one/zero notation that computers use today.

He won most fame as an astronomer. He bought an early telescope and became the first person to map the moon, beating Galileo by four months. True, he did miss the fact that the moon had mountains—Galileo claimed that discovery. But Harriot held his own otherwise. He used sunspots to determine how fast the sun rotates. And the data he gathered on Halley’s comet later helped determine the comet’s path through the heavens. These were dazzling feats.

Alas, the 1500s was a low point in English intellectual life. As Harriot wrote to his friend Johannes Kepler, “I still may not philosophize freely [here]; we are still stuck in the mud.” Whenever he published one of his dazzling discoveries, the public damned him as an atheist or accused him of witchcraft. For this reason he stopped publishing early in life. As one historian said, “He preferred life to fame, and who can blame him?”

But during the late 1500s, the English attitude toward math and science shifted, for a simple reason. Money.

At the time, Spain and Portugal had the world’s best navigators. They could cross even open oceans by using advanced mathematics to determine their latitude and direction. They could also make intricate maps. As a result, Spain and Portugal had a huge leg up in establishing colonies in the Americas.

English ships, meanwhile, had ignorant navigators, and their journeys were mostly limited to pathetic jaunts that hugged the coast; open ocean was too dangerous for most. As a result, England feared they’d missed out on a colonial bonanza.

Given his expertise in astronomy, Harriot was tapped to fix the poor state of English navigation. His patron was Sir Walter Raleigh, who was a darling of the reigning Queen Elizabeth. Raleigh had a charter to establish a colony in what’s now North Carolina, and Harriot’s skills made him the obvious choice to serve as the mission’s navigator.

Raleigh’s main goal at this stage was to trade with Native Americans. The Natives coveted European goods like metal tools and dyed cloth. In exchange, Raleigh wanted gold.

Beyond his commercial ambitions, Raleigh had a scholarly streak and wanted to expand European scientific knowledge. So in addition to serving as navigator, Harriot was tapped to make maps and gather information about plants and animals near the new colony and look for gold.

Harriot’s voyage departed England in April 1585. Several hundred men were crammed onto five ships, which made for a disgusting journey. The ships were only the size of modern yachts, and were therefore crammed with unwashed bodies. One unlucky fellow who bathed in the ocean on the way over lost his leg in a shark attack—which didn’t exactly encourage the others to wash up.

Despite the squalor, Harriot managed to be productive on the trip over. He observed a solar eclipse from the rolling deck one afternoon. More importantly, he spent the trip learning the Algonquin language from two Native Americans onboard, Manteo and Wanchese. They had sailed to England with an earlier crew of explorers and were now returning home.

Harriot’s convoy of ships finally sighted land in June—North America! It must have been a moment of excitement and sheer relief—no more squalid nights onboard. But the colonists quickly ran into disaster, when their supply ship ran aground. Thousands of pounds of rice, beans, biscuits, and other foodstuffs were ruined.

The loss of food pushed the nascent colony halfway to doom. And soon enough, Thomas Harriot accidentally shoved them to the brink.

Again, Harriot’s job for the colony included making maps and searching for gold. This required him to travel far and wide. He tramped through forests and paddled through sweltering swamps, where whole armies of mosquitos attacked him.

But he loved the work. And while he found no gold, he did find botanical riches, like sassafras and tobacco. Using the Algonquin phrases he’d picked up, he also took anthropological notes on the local Pamlico, Croatan, and Roanoke tribes, whom he admired as smart, hardworking people.

Sadly, however, Harriot’s zeal to visit Native Algonquin villages had devastating consequences. He began to notice that, whenever he traveled somewhere, reports would emerge a few weeks later of people dying in that place. It happened over and over. The pattern seemed too consistent to be a coincidence, but he couldn’t make heads or tails of it.

We now know that Harriot was carrying influenza germs, and spreading them among people who had little immunity. But rather than stop going from town to town, Harriot chalked the epidemic up to the appearance of a comet in the sky and kept traveling. Such was people’s mindset then. Even smart, compassionate people like Harriot blamed everything on the stars.

Now again, Harriot’s colony was on shaky ground at this point, after the loss of much of their food. Their backup plan was to trade with the Algonquins. But the flu epidemic so devastated them that the Algonquins could barely hunt and farm enough to feed themselves. As a result, they had little surplus to trade. The food situation for the colonists was becoming dire.

In addition, while Harriot admired and got along with Native Americans, his fellow Englishmen more than lived up to their brutal, ignorant reputations.

One night, after a feast at the English camp, a few Algonquin guests took home a silver cup they’d been handed to drink from at one point. They assumed it was a gift.

This was almost certainly a misunderstanding. But the Englishmen decided that the Algonquins had stolen the cup. They stormed into a nearby Algonquin village, demanding its return. When it couldn’t be found immediately, they burned the village down.

Naturally, the Algonquins retaliated with raids and arson of their own. So then, an eye for an eye, the Englishman attacked back. Which only made the Natives re-attack. At which point, the English—well, you can guess. Burnings and murders began to multiply out of control.

Eventually, rather than trade or just supply food out of mercy, the Algonquins began withholding food from the English. The Algonquins even smashed the fishing traps they’d made for the colonists, hoping to starve them out.

It worked. The food situation got so dire that, nine months after the colony’s founding, the local governor decided to abandon it. Thomas Harriot climbed back aboard his ship with a sigh. What could have been.

Back in England, Harriot told anyone who would listen that a colony could still succeed, as long as people made friends with Native Americans. To this end, he worked hard to convince his patron Walter Raleigh to finance the doomed Roanoke colony of 1587.

As we heard, the Roanoke colony vanished without a trace. Their fate remains a total mystery. It’s likely they either got into another foolish war with local tribes and perished, or else married into the tribes and assimilated. Regardless, the men and women of the Roanoke colony have disappeared in the mists of history.

Roanoke represented a second failed colony in North America. After which Raleigh and other bluebloods lost their appetite for adventures abroad. In fact, about the only person who refused to abandon hope was Thomas Harriot.

To win over skeptics about North America, Harriot began publishing pamphlets about mistakes of previous colonies—including their short-sighted attacks on Natives. Harriot also made suggestions about how colonies could support themselves financially. And it was here where he made a deadly miscalculation.

In his pamphlets, Harriot argued that the best way to support a new North American colony was to focus less on trade and more on agriculture. He highlighted two plants as especially promising.

One was sassafras. Although we now know that sassafras is a mild carcinogen, in the late 1500s, it was considered a miracle medicine. The sassafras tree thrives in sandy soil from Florida up through Maine. The leaves look vaguely like a human hand, and have a citrus-y scent.

Native Americans brewed the leaves into an orange tea, and they used the tea to treat everything from acne to urinary tract infections. Harriot gushed over its, quote, “rare virtues.” It seemed especially promising to battle the scary new disease of syphilis, which was ravaging Europe then. If nothing else, sassafras tea was far milder than existing treatments for syphilis, which used mercury or arsenic.

Thanks to Harriot’s hype, the price of sassafras skyrocketed. Before his pamphlets, you could secure 16 ounces for 18 pounds sterling. In the decade after the pamphlets, the price jumped to 300 pounds—17-fold. An English plantation that grew sassafras, it seemed, would make a killing.

The second plant Harriot promoted was tobacco. On his travels in North America, the Algonquins had taught Harriot how to consume tobacco by drying and burning the leaves, then inhaling the fumes through clay pipes.

And if Harriot was enthusiastic about sassafras, he went absolutely gaga over tobacco. Harriot smoked like probably no one in history had ever smoked before. Native Americans tended to smoke only occasionally, for ceremonial reasons. Harriot made smoking a daily habit, consuming as much as he could get his hands on.

Harriot then introduced this smoking habit to his patron Walter Raleigh. Raleigh in turn spread tobacco to the royal court, which made smoking fashionable. From there, smoking trickled down through every stratum of English society. And when Englishmen started sailing around the world, they carried the habit with them.

That’s how tobacco-smoking eventually conquered the world—through Harriot and then Raleigh. John Lennon of the Beatles even mentioned Raleigh’s influence once in a song called “I’m So Tired.” As Lennon crooned, “Although I’m so tired/ I’ll have another cigarette/And curse Sir Walter Raleigh/ He was such a stupid git.”

If not for Raleigh and Harriot, tobacco-smoking likely would have remained an obscure North American habit, a footnote for anthropologists. Instead, tobacco became one of the most widely abused drugs in history—and caused the deaths of 100 million people in the 20th century alone.

But all that lay in the future. At the time, tobacco and sassafras were hot commodities in England. People called these plants “vegetable gold,” and the high price they commanded convinced the English to found yet another colony in North America.

In 1607, the English established Jamestown in Virginia. And from that point forward, they had a permanent presence in North America. Tobacco and sassafras grown there made many people rich, and this in turn convinced the Crown to establish more colonies elsewhere. Within a century, the rude, backwards English were overseeing one of the largest empires in history.

Unfortunately, the pursuit of vegetable gold also changed the nature of colonization. Again, early colonies focused on trading with Natives, offering them metal tools and cloth.

But with tobacco and sassafras, the colonists assumed they didn’t need the Natives anymore. It was more lucrative to push them off their lands, clear-cut it, and start plantations. As a result, relations with Native Americans quickly turned ugly and then genocidal. The rise of plantations also kickstarted the importation of enslaved labor from Africa.

Thomas Harriot no doubt would have been horrified by all this. But his zealotry for new colonies, and his influence on Sir Walter Raleigh, did help bring these things about.

Neither man, however, lived long enough to see the consequences of what they’d unleashed. Raleigh was actually convicted of treason in 1603 and executed. I’ve put together a bonus episode about this fiasco at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. The bonus also explains how Raleigh’s death, surprisingly, is still causing injustice today, by affecting forensic science in modern courtrooms. You wouldn’t think a man who died 400 years ago could have such an influence, but Raleigh does. That’s patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

After Raleigh’s conviction for treason, Harriot kept plodding away at his math and science. He became an early champion of telescopes, which were called “Dutch trunkes” then, given their origin in Holland. And again, he matched wits with Galileo and studied sunspots.

But Harriot would not have much time to enjoy his new astronomical toys. One day in 1615 he noticed a little ulcer on his lip. It kept getting bigger and uglier over the next few years, and eventually blossomed into a tumor. His enthusiasm for tobacco had caught up with him, and in 1621, he became the first known person in history to die of smoking.

Perhaps this was karmic revenge. Harriot had always championed the Natives in North America, but he inadvertently killed many of them, both by spreading influenza and especially by pushing to colonize their land. But the Natives’ sacred tobacco plant got him in the end.

Because of his refusal to publish much of his math and science, Harriot has remained an obscure figure in science history. Only lately have scholars started to appreciate his outsized influence on world events.

One of the few honors he received came back in 1970, when astronomers named a crater on the moon after him. Fittingly, given his obscurity, the crater is on the back side, where no one can see it from Earth. But it’s always there, looming above us, nevertheless.