There’s no question that Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci was brilliant, but he only finished a fraction of the projects he started. Sam Kean argues that the problem was his inability to focus—his own intelligence kept getting in the way.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

It’s a moment historians drool over.

In the early 1500s, Leonardo da Vinci was chatting with friends in a piazza in Florence. They were discussing Dante’s Divine Comedy. Someone asked Leonardo his opinion about one passage. And Leonardo began stroking his long red beard. He was stumped.

Then, none other than Michelangelo entered the piazza—head down, striding fast. As usual, he was wearing filthy clothes and muttering to himself. But Leonardo nudged his friend and said, Let’s ask Michelangelo. He can explain the passage.

Imagine that. Two titans of the Renaissance, about to trade opinions on the Divine Comedy. What an amazing historical moment.

Except, things didn’t turn out that way. Michelangelo, around age thirty, turned and scowled at the fifty-something Leonardo. He assumed Leonardo was mocking him

“Explain it yourself,” he spat. Then he started mocking Leonardo in return. “You, who designed a giant horse to cast in bronze and failed. And then abandoned it out of shame.”

Leonardo flushed red, and turned away in embarrassment. Michelangelo stomped off. And that ended that.

Historians have long cherished this moment for the contrast it reveals about the two artists. Michelangelo was feisty. He saw Leonardo as a rival, and was prone to quarreling.

Leonardo, meanwhile, was chatty and generous of spirit. But as the insult about the horse sculpture shows, he was also sensitive about his less-than-flattering reputation. A reputation as a bungler, a failure, someone worthy of contempt. What was that about?

Well, today, I’d like to unpack that side of Leonardo. Because there’s good evidence, from then and now, that this legendary Renaissance man was brilliant, original, groundbreaking—and wildly overrated.

Leonardo’s fame rests on two things. His art and his science-slash-engineering. Although in truth, it’s hard to separate the two.

In 1483, when Leonardo was thirty-one, he applied for a patronage with the Duke of Milan. And his application letter is completely over the top. In it, Leonardo bragged about his expertise with an absurd number of technologies—bridges, dikes, ships, catapults, cannons, canals, covered wagons, and more. He also claimed to sing like a nightingale—and, oh, was the best artist in Europe.

Now, the duke obviously didn’t believe Leonardo could do all this. No one person could. Still, Leonardo’s artistic talents were real. So in 1489, the duke commissioned Leonardo to create a statue of the duke’s father riding a horse. It would stand 26 feet tall, and require 70 tons of bronze—the largest metal statue in history until then. And it quickly became clear that the Duke … was right to be skeptical of Leonardo.

Leonardo’s initial design had the horse rearing on its hind legs. A dramatic pose. But a pose that, as many people pointed out, would be ridiculously unstable for a 70-ton statue. Leonardo tried to modify his vision by including a fallen soldier at the horse’s feet, which he could connect to the body for stability. But he eventually abandoned the rearing horse altogether for a conventional horse statue on all fours.

With that plan in mind, Leonardo threw himself into the task—albeit haphazardly. He began drawing horses, plopping down in local stables to sketch them. But he soon got carried away writing a treatise on horse anatomy.

He then let his imagination wander more, and started a second treatise on a new method of casting statues. Daringly, instead of the traditional method of casting different pieces of his horse statue separately and melding them together, Leonardo promised to use his engineering genius to cast everything at once.

This plan involved building a huge, finely detailed clay model of the horse. He’d then coat that model in wax; cover it with more clay; and bury the whole thing upside-down in sand. He’d then start fires over the sand to melt the wax, which would run out through channels he’d carved in the bottom. Finally, molten bronze would be poured in to replace the wax. And voilà, a giant bronze horse.

It was innovative stuff. But artists with more experience had doubts. Designing the channels for the wax to run out would be tricky. They also feared that the tremendous heat of all that molten bronze would crack the clay mold and ruin everything.

Leonardo plunged ahead anyway, and in November 1493, he revealed the clay model of the horse at a wedding. People were stunned. The horse was brilliant—so life-like. The Duke couldn’t wait to see the final thing.

And wait he would. Leonardo promised to begin casting around Christmas. But December passed, and nothing happened. January, too. Then February slipped by, and March. Still no progress.

It turned out Leonardo was having trouble with his grandiose plans. Instead of burying the model upside-down in sand, he had to turn it on its side, for stability. But that required redesigning all the channels for the wax to drain, since they weren’t on the bottom now. Outside the studio, he was also getting distracted with his treatise on horse anatomy.

Finally, in November 1494, a full year after the model went on display, the duke had had enough. Leonardo was nowhere near ready to begin casting. And unfortunately, one of Italy’s endless wars was starting. So the Duke seized the 70 tons of bronze and melted it down to make cannons. The horse statue was dead.

As a final insult, when French soldiers later invaded Milan, they had a grand time using the clay model for target practice. Afterward, Leonardo’s failed horse statue became a punchline among Italian artists like Michelangelo.

Unfortunately, the horse fiasco set a pattern for Leonardo’s career. To start off, how many artworks by Leonardo can you name? There’s the Mona Lisa, obviously. The Last Supper. Beyond that…it gets harder.

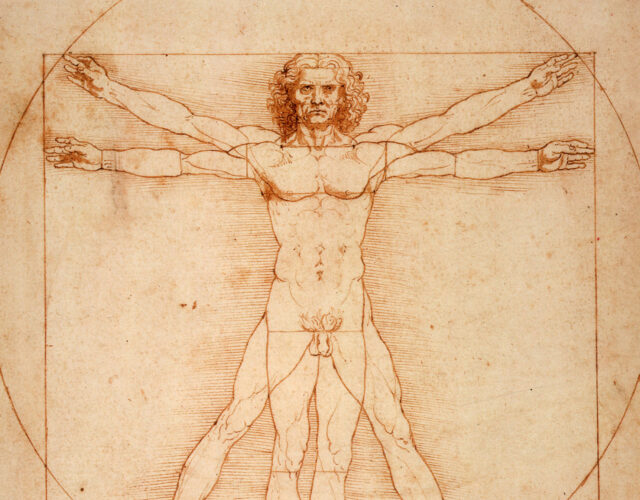

Arguably, his next-most-famous work is a notebook sketch—the Vitruvian Man, that dude in a circle spreading his arms and legs. It’s certainly arresting, but hardly a major achievement.

And the horse sculpture wasn’t the only notable flop. His most notorious failure involved a mural in Florence—another doomed blend of artistic ambition and half-baked science.

Leonardo moved to Florence in 1500, and quickly dazzled everyone with his wit and talent. Not to mention his dandy clothing. This included rose-colored tunics with fur-lined collars. And while he was something of a loner, he had many warm acquaintances—including none other than Niccolò Machiavelli.

In 1503, city leaders asked Leonardo to paint a mural inside their majestic city hall. It would stretch 55 feet wide, and would commemorate an important local battle. Given the scale, the subject, and the prestigious location, it seemed destined to be Leonardo’s masterpiece.

Characteristically, he threw himself into the project, taking pages and pages of notes about the battle.

Just as characteristically, though, he kept getting distracted. He’d take half a page of notes, then start doodling in the margins. Doodling bird wings. Or flying contraptions. He finally abandoned the notes altogether, and decided to improvise the scene.

But after six months, Leonardo hadn’t even finished a preliminary sketch of his would-be masterpiece. City leaders started grumbling. But one of them had an idea.

Leonardo’s friend Machiavelli, being Machiavelli, commissioned a second mural in the same room as Leonardo’s. And for that mural, he selected … the upstart Michelangelo—Leonardo’s biggest rival. As a motivational ploy, it was pure Machiavellian genius.

And it did light a fire under Leonardo. For a while. He finally finished a full-scale drawing of the mural. But before long he got distracted again. One distraction involved designing the platform he would paint on. An engineering genius like Leonardo couldn’t just stand on a regular scaffold—no, no, no. His scaffold was new-fangled and intricate, with a giant accordion lift to raise him up and down.

He also began experimenting with different methods of applying paint. Sadly, his recent painting The Last Supper was already suffering damage then, with the paint rapidly flaking off.

Leonardo didn’t want his new masterpiece to suffer similar damage. So he devised a way to apply paint on a plaster surface that was coated with turpentine, resin, and wax. He tested it with some hurried experiments, then raced forward.

Unfortunately, the technique didn’t work at full scale. The plaster didn’t stick to the wall well, and all the paint he applied started dribbling down. He had to light fires perilously close to the surface to dry it.

By this time, Leonardo’s deadline for the mural had long passed. Then in June 1505, disaster struck. A thunderstorm swept in and water leaked into city hall. The already soggy plaster turned into a soggy mess. Leonardo would have to start over completely.

Except, he didn’t. He got distracted with still other projects. And despite the prestige of the commission, he soon abandoned his would-be masterpiece entirely.

Sadly, this was something of a pattern with Leonardo. Over his forty-year career, he finished just fifteen paintings. Fifteen! Scores of others, he just abandoned partway through.

Now, in relaying stories like this, I don’t mean to insult Leonardo’s talent. He was one of the most talented artists ever. He was not lazy, either. He worked long and hard and constantly had a dozen different projects going. But time after time after time, he abandoned projects before completion. So what was going on?

In short, Leonardo’s problem was temperamental. Even psychological. He lacked what the Germans call sitzfleisch.

Sitzfleisch means “sitting flesh.” It’s a slang term for the buttocks. But it also means sitting your buttocks down…to do some work. It’s what Mark Twain meant when he defined writing as “the application of the seat of the pants to the seat of the chair.” But that wisdom applies to other endeavors as well. Sometimes, you just have to sit down and focus.

Consider Michelangelo. He was a moody ass, but man, did he work hard. People in fact avoided him because, when he was working, he refused to stop and wash his clothes or even bathe. He was too focused.

Leonardo was the opposite. He couldn’t focus. He’d sit down to work and suddenly get distracted with some triviality, some oddball thought. His notebooks are crammed with half-baked ideas scribbled into the margins. Thoughts on nightingale tongues. On motorized lions. On sneezing.

All of which is charming! But his flitting, magpie mind prevented him from sitzing his flesh down and finishing anything. Time after time, Leonardo either drew up grandiose plans without thinking them through, or simply got distracted and couldn’t finish what he started.

And while Leonardo’s artistic output simply fell short of his promise, in technical fields, he was kind of a flop.

Scientifically, he dabbled in botany, geology, optics, ballistics, linguistics, and physics—but made no deep marks in any of them.

Engineering-wise, he sketched out plans to build automobiles, looms, diving suits, submarines, parachutes, and helicopters. He filled at least seven-thousand notebook pages with such ideas.

But guess how many of those inventions he actually built. Not one. They were mostly just fleeting thoughts—and in some cases, not even very good thoughts.

Take his flying contraptions. He returned to such devices over and over. Sketching out strap-on wings, or helicopters powered by treadmills. They’re powerful images—that age-old dream of flight! Who wouldn’t be captivated?

But every one of them was laughably impractical. He seemed not to grasp the basic truth that, compared to birds, humans beings have far fewer muscles in proportion to our body size. We can’t generate nearly enough power to lift off the ground. Other inventions show the same basic shortcoming: he simply didn’t grasp the underlying science.

Now, I realize I’m being a Scrooge here, unduly harsh on Leonardo’s art and his science. A few paintings he did complete are unquestioned masterpieces. And he made real contributions to a few areas of science, like anatomy.

Plus, you could argue that his notebook sketches of flying machines and other marvels perhaps acted as spurs to other people’s imaginations. Much like science fiction, perhaps the drawings awakened people to new possibilities—which is something important.

Except, Leonardo never published his notebooks. So they couldn’t have inspired people. Instead, he horded his ideas, like a dragon hording gold, and refused to show anyone. The vast majority of his work never saw the light of print until the 1880s. By which point most of his ideas were hopelessly outdated.

In the end, I go back and forth on Leonardo. Sometimes I feel generous, and say that Leonardo was deep and philosophical. Maybe he considered process more important than the final product. Sometimes I feel less generous, and peg him as a sort of court jester of science—full of wit, but not someone to take seriously. Most of the time, I simply sigh over what might have been. If he’d just applied himself.

Now, Leonardo is not alone in science history for lacking sitzfleisch. In next week’s episode, I’ll examine Robert Oppenheimer, a Leonardo-like figure who won fame on the Manhattan Project, but never fulfilled his immense promise as a scientist. There was also something of Michelangelo in Oppenheimer—he had a nasty side, and even tried to murder one of his teachers once. It’s a wild story. So tune in next week.

Regardless of how I feel about Leonardo on a given day, he fell well short of his promise. And I think his life illustrates an important but overlooked point about science—that it’s a public endeavor.

Most people think about science in terms of discoveries. Galileo discovered X, Marie Curie discovered Y, and so on. But the real power of science isn’t smart individuals. It’s a smart system. Science is a process above all—a way of checking assumptions.

Even really smart people have biases and blindspots. Science overcomes those blindspots by setting up strict rules for testing ideas. Specifically, whenever someone makes a claim, the wider community has to poke and prod and scrutinize it. And only after the community weighs in does something count as a discovery. In some sense, then, a private discovery doesn’t count as science at all.

And maybe that was Leonardo’s biggest shortcoming. Unlike most later scientists, Leonardo horded his ideas and never opened them to criticism. And because of his scattered mind and refusal to publish, Leonardo had zero impact on the history of science and technology.

It’s trendy to nowadays to talk about creativity and achievement in terms of range. Explore—roam—jump from passion to passion. Develop your range. And no one in history had more range than Leonardo. What a mind.

And yet—there’s something to be said for grit as well. For focus, for single-mindedness. For applying the seat of the pants to the seat of the chair, and seeing a painting or two through.