Why does February have only 28 days? Why do days have 24 hours but hours have 60 minutes? And while octagons have eight sides and octopuses eight arms, why is October the tenth month? Most of us just shrug at such questions. But not Thomas Schall. He wouldn’t let things like that stand. He understood that calendars and clocks are human inventions. So why not invent better ones?

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Padmini Raghunath

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

Thomas Schall decided to treat himself to a cigar. Why not? He had a lunch break coming up, and in 1907, a bigshot lawyer like him could smell like cigars after lunch and no one would bat an eye. Besides, his case was going swell—in the bag. So Schall and a colleague wandered outside the courthouse in Fargo. And just like you might find a food truck today, they found a cigar wagon and selected two fine stogies.

Schall’s colleague was old-fashioned, and lit his cigar with a match. Not Schall. He loved technology—anything new-fangled. So he lit his cigar with the electric lighter on display in the wagon. What a marvel.

It was the worst decision of Schall’s life. Because when he bent down and started inhaling <BOOM> the electric lighter shorted out and exploded in his face.

The resulting injuries left Schall blind, and he naturally assumed that his career—if not his life—were over.

He was wrong. Not only did Schall resume practicing law, he got himself elected to Congress—the first blind person to serve in the U.S. Capitol. And while there, Schall dedicated himself to one idea above all—an idea perfectly in line with his progressive, pro-technology mindset. Reforming our messy, lopsided, archaic, and maddingly inconsistent monthly calendar.

Have you ever considered how strange clocks and calendars are?

Why does February have only 28 days? Why do days have 24 hours, but hours have 60 minutes? And while octagons have eight sides, and octopuses eight arms, but October is the tenth month?

Most of us just shrug at such questions. Life isn’t always logical. But not Thomas Schall. He wouldn’t let things like that stand. He understood that calendars and clocks are human inventions. So why not invent better ones?

Schall was born in 1878. When his father died two years later, he and his now-indigent mother moved to Minneapolis. Instead of attending school, Schall sold newspapers on the street, he slept in cardboard boxes at night. Because he could sing and dance, he also joined the circus for a spell. Kids really did that back then.

After some more travails, Schall did eventually attended high school, where his oratory skills won him renown. He parlayed those skills into a law degree, and quickly became a prominent Minnesota lawyer.

Then the ill-fated cigar lighter exploded in his face. Schall didn’t go blind immediately. In fact, he returned to court that very afternoon, despite having scorched arms. But he noticed his vision was blurry, and it kept deteriorating over the next few months.

Schall and his wife Margaret exhausted their life savings trying to help him. When the legitimate doctors ran out of ideas, they moved on to the quacks. They sold all their furniture and books to raise money. Nothing helped. Schall was soon completely blind.

He fell into a trough of despair. But his wife refused to let him quit on life. Margaret offered to become his business partner—writing his correspondence, reading his mail, chauffeuring him around. With her support, his law practice picked up again. And in 1915, he won a longshot campaign for Congress as a progressive, Teddy Roosevelt–style Republican.

In Congress, he did many things, of course. But he became associated with one idea above all—calendar reform.

You see, progressives like Schall hated how illogical the calendar was. Why do months have different numbers of days? If something was a yard long, you wouldn’t divide the first foot into 12 inches, and the second into 11. It was stupid. As Schall said, “We have standardized everything except our measure of time—the very thing we use the most.” He knew we could do better.

The problem is, any attempt to standardize the calendar gets snagged on the fact that the number of days in a year is lopsided. Blame God or arithmetic, but you simple cannot break down 365 into nice, even numbers. The only possibilities are 5 months of 73 days, or 73 months of 5 days. Both arrangements are ugly and impractical.

However, 365 is very close to 364. And 364 does break down into appealing numbers. Like 13 by 28. That is, 13 months, of 28 days each.

A French philosopher invented this 13-month calendar in the mid-1800s. And as long as he was mixing things up, the philosopher also ditched the pagan names of the months, too. Instead, he renamed months after human geniuses—Charlemagne, Homer, Moses, King Frederick II.

Whimsically, the philosopher also named every single day after someone, too. For instance, the 10th day of Frederick II month was Gustavus Adolphus day. The 18th day of Moses became Theocrats of Tibet day. Not to be confused with the 19th of Moses, which was of course Theocrats of Japan day.

Not surprisingly, your average French peasant hated this calendar. Who the hell were the Theocrats? But other reformers picked up on the general idea—including Schall, who wrote a bill in 1919 for the United States to adopt this calendar.

Wisely, Schall ditched the list of geniuses and preserved the traditional names of the twelve months. Instead, he suggested squeezing an extra month between February and March. He called this Vern. Vern kinda sounded like someone’s uncle, but really stood for vernal—as in spring, because the vernal equinox would take place during the month.

The one awkward feature of the 13-by-28 calendar was that it left out that last day of the year. So reformers like Schall suggested tacking an extra day on after December—a 24-hour worldwide holiday. Some reformers called it “Blank Day.” It wouldn’t be a Saturday, nor a Sunday, nor anything. It’s just blank.

Now, if adding Blank Day sounds strange, well, remember—we already shoehorn extra days into the calendar now. They’re called leap days—February 29ths. So would Blank Day really be that different?

And Schall marshaled some impressive arguments to support his calendar. World War I and the Great Influenza pandemic had recently overturned the old world order. Prohibition started during this time as well, as did reforms like eight-hour workdays. People were rethinking everything, and technology was making great strides. Tractors had replaced plows, and automobiles buggies. So why not abandon our creaky, kludgy calendar, and install something better?

To his frustration, Schall’s calendar bill stalled in Congress. But he kept stubbornly reintroducing the bill year after year. And he found a valuable ally in George Eastman, the business magnate who headed the Eastman-Kodak film company.

Eastman argued that, in addition to being more logical, the regularity of the new calendar would benefit businesses.

Eastman pointed out that, when some months have 30 days, and others 31 or 28, it’s hard to compare financial data between months. Compounding the problem, salaries and rents are fixed monthly. But depending on where the weekends fell, shops were open a variable number of days, meaning revenues also varied widely. Schall’s 13-by-28 calendar eliminated those problems in a stroke. Every month was consistent.

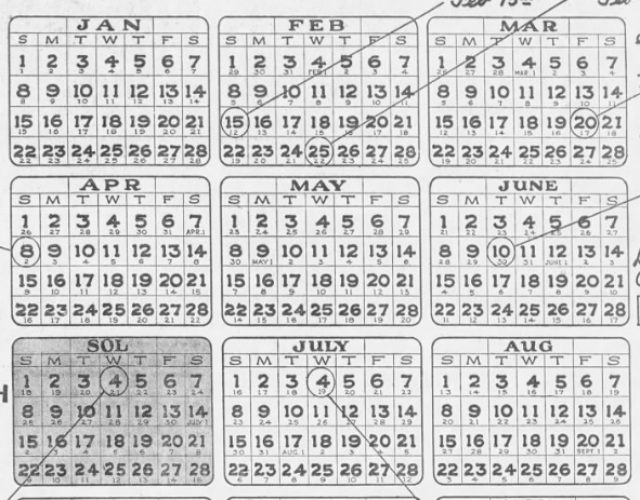

The 13-by-28 calendar had another slick feature, too. It’s perennial. That is, every date always falls on the same day of the week. January 1st would always be Sunday, for instance. In fact the 1st, 8th, 15th, and 22nd of every month would be Sundays. The 2nd, 9th, 16th, and 23rd would then be Mondays. And so on. Like blank checks, you could buy calendar pages in bulk, because every month would be regular.

This regularity does not happen with the current calendar, since dates migrate throughout the week. So do holidays. Which means schools and sports teams and businesses have to draw up fresh schedules every single year. It’s a headache.

But again, a 13-by-28 calendar eliminates those problems. You’d always know what day and date every business quarter or semester starts. Holidays, too. It would free up so much mental space.

These arguments convinced a lot of people to back Schall and Eastman’s calendar. Eastman’s National Committee on Calendar Simplification conducted a survey of 1400 businesses. And 80 percent favored a standardized calendar. The National Academy of Sciences backed it as well—like the metric system, the new calendar just made sense.

But, alas. Amid all this support, there was one factor that Schall hadn’t accounted for. The power of religion.

Thomas Schall’s nemesis in calendar reform was a congressman from the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Sol Bloom.

Now, Bloom was actually an even bigger calendar nut than Schall. Schall just wanted a more functional calendar. But Bloom was a calendar obsessive. He apparently used to buttonhole people and just blab about calendars for hours. His wife and daughter would cover their ears and run from the room whenever he got going.

Oddly, though, despite his general love of calendars, Bloom despised the Schall calendar. Why? Because of Blank Day—that worldwide holiday on the 365th day of the year. To Bloom, Blank Day was an abomination unto the Lord.

Remember, Blank Day fell outside the jurisdiction of normal days of the week. It wasn’t a Saturday or Sunday or anything. It just was.

The problem here is that God made the firmament and the heavens in six days, then rested on the seventh—the Holy Sabbath, which must be honored. But Blank Day would stretch the time between Sabbaths to eight days—longer than God intended.

To Bloom, a devout Jew, this was a catastrophe. And he wasn’t alone in thinking this way. He soon rallied several fiery Christian preachers to his side, all of whom denounced calendar reform as blasphemous. Bloom also argued that reform would violate the First Amendment by threatening the free exercise of religion.

After that, Schall’s new calendar never stood a chance. It was hard to be on the opposite side of God back then and win a debate. Schall served several more years in Congress, and eventually got elected a U.S. Senator. He never lost his love of technology, either. He apparently flew home from the Capitol sometimes to his house in Maryland in an autogiro, one of those wacky plane-helicopter contraptions. But when Senator Schall died in 1935, his dreams of a new and better calendar died with him.

Still, the flame of calendar reform never quite died out. In fact, several reformers still tend it today. And they’ve come up with answers to the objections that doomed calendar reform in Schall’s time.

Again, religious folk hated Blank Day because it extended the time between the Sabbaths. So, one modern workaround involves simply changing the meaning of a day. In this schema, the last day of December and first day of January would each, by fiat, stretch 36 hours long, leaving exactly six so-called “days” between Sabbaths. The downside to this idea—beyond being silly—is that New Year’s Eve would arrive at what’s effectively noon. Who wants to sip champagne when the sun is high in the sky?

A more sensible reform proposes ditching Blank Days altogether and defining a calendar year at 364 days. Then we’d just schedule a makeup week every so often, for both leap days and the missing 365th day. It’s a bit awkward, but would preserve the proper time between Sabbaths. Crisis averted.

Now I am being a bit facetious here in talking about the supposed catastrophe of extra days between Sabbaths. But in all seriousness, any attempt to reform the calendar would require the backing of all major religions, which take the calendar seriously. Getting their support is vital.

And honestly, I can take the religious objections more seriously than other objections. Most reform calendars propose starting the 1st of every month on a Sunday. But if you do that, you end up with a Friday the 13th every month. Which means thirteen Friday the 13ths! It’s like bad luck squared. It gives superstitious people the heebie-jeebies.

Then there’s the most common objection of all. One calendar reformer told me about giving a talk a few years back on the 13-by-28 calendar. When the talk finished, two young women approached him.

One loved the new calendar. She immediately saw the advantages and realized how much it would simplify life. The other young woman looked sour. When the reformer asked why she looked sour, she pouted, “Because my birthday would always be on Wednesday.”

The reformer was stunned. This woman was willing to sabotage calendar reform entirely—willing to let waste and inefficiency continue, and abandon a logical, smooth-functioning system—all because of her birthday? It seemed so…petty, so small-minded. Was she serious?

Yes. And she’s not alone. In some ways the birthday objection is the single biggest obstacle to calendar reform. People can and do raise other issues about new calendars. Deep down, though, many people just care about their birthdays.

But, what the hell. Calendar reformers have a crazy solution for this problem, too. They point out that the Queen of England, Elizabeth II, was actually born in April. But she celebrates her official state birthday in June, when it’s sunny and convenient. Why can’t we civilians do the same? After all, who wouldn’t want to feel like a queen for a day?

When I hear people complain about Tuesday birthdays, or unlucky 13s, I feel like despairing. Can’t we see beyond ourselves? I sometimes think of reformers as calendary Cassandras—doomed to be correct, even though no one listens to them.

At the same time, are we really surprised? People are people, with all our glory and all our faults. We’re more blind in many ways than Thomas Schall. And yet, if you really believe, like Schall did, that people will just listen to logic—well, that blind spot is probably the most illogical idea of all.