In the 19th century, theoretical biologists grappled with a wild new idea: evolution. Decades before Darwin emerged with his theory, two of his predecessors hashed out their theories in the public sphere. And what was the thing they used to test those theories? Egyptian mummies—specifically those of ibis birds. What followed was a poorly developed experiment that set back our understanding of evolution for years and became fodder in a battle between rival scientists.

Further Listening: Our sister podcast, Distillations, recently explored the historical roots and persistent legacies of racism in American science and medicine including how the study of human remains intersects with race. Check out 2023’s Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race season to learn more.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

Samuel Johnson once said that no one is under oath during a eulogy. When speaking about the recently departed, we can exaggerate their good qualities and downplay their bad ones. It happens all the time.

But what Johnson didn’t say is that a eulogy can also be a weapon.

In last week’s episode, Napoleon conquered Egypt in 1798. His scholarly savants looted the country, helping themselves to art and artifacts.

And some of those savants realized that the artifacts could help test a controversial new theory in science—evolution.

Nowadays, if you say evolution, the first name that pops to mind is Charles Darwin. But Darwin wasn’t the first person to propose the idea. He had predecessors.

One predecessor was someone you might remember dimly from high-school biology class. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. Larmarck is usually portrayed as a foil to Darwin, something of a buffoon.

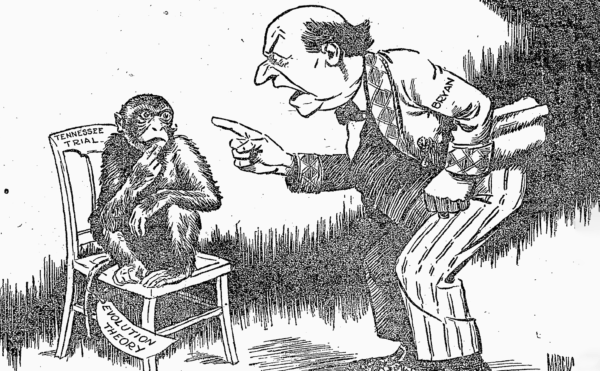

One big reason he’s looked down upon is that Lamarck got into a dustup about evolution with another biologist. George Cuvier.

As we’ll see, Cuvier was not above fighting dirty. He was half Darwin, half Machiavelli. Cuvier also had something of a secret weapon in his arsenal when fighting Lamarck. Thanks to Napoleon, Cuvier had access to mummies.

If you haven’t heard of Georges Cuvier, don’t worry. But that fact would have stunned people in 1800s France—including Cuvier himself. He and everyone else alive considered him one of the greatest minds in history.

Cuvier had bushy hair, a long nose, and a gigantic noggin—a veritable pumpkin atop his shoulders. Although he came from modest means, his quick mind propelled him to the top of the French scientific world around 1800. He served as a professor of natural history and advised many important government agencies. In fact, he soon became Baron Cuvier. He had power.

Baron Cuvier promoted two big ideas. The first was that species of animals sometimes go extinct. Now, that probably doesn’t sound remarkable today, but it was a radical idea at the time.

People in Europe then believed that God had created all the animals on Earth as outlined in Genesis. And it was heresy to suggest that some of God’s creations could disappear. Didn’t that imply that they were less than perfect? But how could they be if God had made them?

Cuvier suspected otherwise, based on the fossil record. The first clue came when he recognized an ancient type of elephant. It was first unearthed near Paris, and had no living descendants. That got Cuvier thinking.

And the more he looked around, the more evidence he saw for creatures going extinct. Fossils of giant sloths. Frozen bits of wooly mammoths. Such creatures simply don’t exist anymore.

Now, some people refused to believe Cuvier. One was Thomas Jefferson. When Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark wandering across North America, he told them to keep their eyes peeled for giant sloths and mastodons. Jefferson was convinced they still existed.

But, no. All those creatures died out long ago. And it was Cuvier who established their disappearance as a scientific fact.

Cuvier’s second big idea was something called the correlation of parts. This said every animal has a certain cluster of traits—and that you can’t change any one of those traits without changing the whole animal.

For example, consider a lion. It’s got big jaw muscles and sharp teeth for tearing flesh. It also has claws to bludgeon prey, and forward-facing eyes for the sharp, binocular vision necessary to hunt game. Other carnivores follow a similar body plan.

Now consider a zebra, a creature that eats grass. It’s got hoofs for speed, and flat teeth for grinding plant matter. It’s also got eyes on the side of its head. That way, it can see threats like lions coming from both directions. And again, most grass-eaters share those traits.

The point is that all the parts work together seamlessly. If a zebra had sharp fangs, it would die. Fangs can’t grind grass. Or if a lion had eyes on the sides of its head, it couldn’t hunt. Again, certain traits go together, and changing any one trait would hinder the animal, probably fatally.

Cuvier believed so deeply in the correlation of parts that he used to make a wild boast. He said that if you gave him a single bone from an extinct creature—or even a single tooth—he swore he could reconstruct the entire animal.

It’s an impressive claim. But it’s not 100 percent true. After all, let’s say you’re a biologist, and let’s say you’ve never seen an elephant. If someone gave you the skeleton, you could guess it was a mammal. But your reconstructed elephant would probably look like a giant furry hamster.

That’s because the most conspicuous part of an elephant—its trunk—would be missing. You can’t predict a fleshy feature from a tooth. Cuvier had an impressive mind, but his belief about the tight correlation of parts would eventually get him into trouble.

So, that was Baron Cuvier. But what about his antagonist, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck?

Lamarck became a biologist in a roundabout way. His pushy father made him join the seminary when he was young. But when his father died, Lamarck dropped out, bought a creaky horse, and galloped off to join the Seven Years’ War. He was seventeen years old.

Lamarck eventually earned a promotion to officer. But Lt. Lamarck’s career ended humiliatingly. His men began playing a game that involved lifting the tiny Lamarck by his head. They eventually injured him, and he had to quit soldiering.

But the military’s loss was biology’s gain. Lamarck returned to school and became a renowned zoologist. His specialty was invertebrates—leeches, jellyfish, slugs, octopuses, anything slippery. Most biologists then disdained such creatures, but Lamarck showed what a rich class of animals they are. In fact, he invented the term invertebrates for them. Then, in 1800, he went one better and coined the term biology for his whole field of study.

But minting words is not what Lamarck went down in history for. That involved his early but misguided theory of evolution.

First, let’s focus on what Lamarck got right. He believed that all creatures great and small descended from a single common ancestor. He also believed that planet Earth was old—vastly older than the Bible said.

Unfortunately, Lamarck got other things wrong. Most importantly, he claimed that creatures evolved within their lifetimes.

For instance: he suggested that wading shorebirds naturally wanted to keep dry. So they’d stretch their legs to keep their tail feathers above the water. And each day, their legs would stretch microscopically farther. As a result, he argued, the birds eventually evolved long legs. Those long legs were then passed down to their offspring.

In a similar way, Lamarck said that giraffes got long necks by stretching up to reach the very tops of trees to eat leaves. They then passed those necks on to baby giraffes. The process supposedly worked in human beings, too. Considers blacksmiths. After swinging hammers year after year, blacksmiths supposedly pass their impressive musculature down to their children.

Overall, Lamarck saw animal bodies as quite plastic. He even talked about animals willing themselves to change, by following instinct and urges.

Nowadays, we know that Lamarck was off base here. Body plans are far more rigid than he suggested. Giraffes can’t just will themselves to have a longer neck. Traits like that are largely set by DNA.

This was a pretty big mistake on his part. And as a result, Lamarck is often painted as buffoonish in textbooks. Again, he’s the foil to Charles Darwin’s much more correct theory of evolution.

But I think that’s unfair to Lamarck. He was one of the first people in history to propose that evolution occurred, as well as descent from a common ancestor. Yes, he got some of the details wrong, but those were bold ideas in the early 1800s.

Unfortunately, in proposing evolution, Lamarck drew the wrath of none other than Baron Cuvier.

Cuvier and Lamarck actually collaborated when they first met in late 1700s Paris—if not as friends then as friendly colleagues. Temperamentally, though, they were too different. They slowly grew to dislike each other. And the idea of evolution in particular enraged the baron.

Remember, Cuvier believed in the correlation of parts. All an animal’s parts fit together seamlessly. Teeth, claws, eyes, everything. So how could any one part evolve or change? If it did, the animal’s perfect balance of parts would fall apart. Evolution was therefore impossible. Species were fixed.

But, as a good scientist, Cuvier didn’t just rely on arguments. He wanted evidence. And he found it in ancient mummies.

In short, Cuvier said that if evolution did occur, then we should see evidence in ancient mummies. If cats or birds from way back then looked markedly different than cats or birds now, evolution had occurred. If they didn’t, evolution had not occurred.

Now, back then, this was a novel approach to resolve a biological controversy. Naturalists then were mostly cataloguers. Like Carl Linnaeus and his elaborate genus-species naming system. Biologists just collected things. They saw what was out there, and sorted them. Most biologists didn’t even care about behavior.

Cuvier did something different. He had a question in mind. Did animals evolve and change over time, or not? Then he went searching for evidence to support or refute that hypothesis. It was a modern attitude.

So Cuvier started examining the ibis mummies that Napoleon’s savants had brought back from Egypt. Cuvier then compared those mummies to modern ibis specimens.

And lo and behold, he found that they looked exactly the same. The birds had the same beaks, the same plumage, the same bones. They hadn’t evolved at all. Lamarck was therefore wrong. Evolution did not occur.

Now, Lamarck didn’t take this criticism lying down. He argued that there was no reason for ibises to have evolved. The environment of ancient Egypt was pretty much the same in the 1800s as it was in 2000 BC or whatever. The same sand, same heat, the same predators. Nothing would drive the ibises to change. Therefore, they didn’t.

Today we know that Lamarck was largely correct. Without environmental drivers, evolution can stand still for ages. Plus, we know that Earth is billions of years old. So a lack of evolution over a few thousand years means nothing in the grand scheme of things.

But to most people back then, Lamarck’s arguments looked weak. Meanwhile, Cuvier had real evidence in favor of his ideas. Add in Baron Cuvier’s political power and superior social status, and the outcome was inevitable. Cuvier won the debate. Evolution had seemingly been put to the test—its first real test—and it had come up short.

Now, perhaps over time, Lamarck could gathered some evidence of his own and won his scientific peers over. Unfortunately, Lamarck didn’t live much longer after this and lost all chance to defend himself.

Lamarck’s academic position had always been precarious. He studied worms and slugs, things no one cared about. Then he started promoting wild, heretical theories about evolution.

He’d also slowly been going blind. This forced him to retire early. Lacking fame and income, he soon became a pauper, wholly reliant on a daughter’s care. When he died in 1829, he could afford only a so-called rented grave. Meaning that his remains got just five years’ rest underground before they were unearthed and dumped into the Paris catacombs to make room for a new occupant.

But the biggest blow to his posthumous reputation came courtesy of Cuvier.

As one of his many official jobs, Cuvier composed eulogies for the French scientific academy’s main journal. And he used these eulogies to undermine colleagues he did not like.

Cuvier’s specialty was damning with faint praise. He opened Lamarck’s obit by lauding his late colleague’s dedication to vermin—creatures no one else cared about.

Still, honesty then compelled Cuvier to point out the many, many times his dear friend Jean-Baptiste had strayed into ridiculous speculation about evolution. Cuvier also turned Lamarck’s gift for imagery against him. He sprinkled the essay with caricatures of elastic giraffes and soaking-wet stork butts. These became indelibly linked to Lamarck’s name.

Cuvier summed things up by saying, “A system resting on such foundations may amuse the imagination of a poet, but it cannot for a moment bear the examination of anyone who has dissected the hand, the viscera, or even a feather.” Overall, the eulogy deserves the title of “cruel masterpiece” that one science historian gave it.

In a Machiavellian way, and you have to hand it to the Baron here. To most of us, writing those eulogies would have been a pain in the neck. But Cuvier saw that he could parlay this burden into great power, and he had the savviness and wit to pull it off.

I find this story intriguing for several reasons. First, history tends to sort people into winners and losers, into heroes and villains. In science history, the heroes are the ones who come up with true theories, while the villains focus on wrong ideas.

But things aren’t so clean with Cuvier and Lamarck. Cuvier was wrong about evolution. But he was correct about extinction, a very important idea in biology—especially nowadays.

Meanwhile, Lamarck was correct about evolution occurring, but he got pretty much all the details wrong. It’s ambiguous who to root for here.

I also love that the story hinged on mummymania. Had Napoleon not invaded Egypt with his savants, and had mummies not been such an object of fascination for people, Cuvier’s ibis test never would have happened.

As it was, the test did happen, and the results set back the acceptance of evolution in Europe for decades, especially in France. French biologists all remembered how silly the mummies made Lamarck look, and they trembled in fear of being humiliated by another Cuvier.

Finally, I love seeing how the public attitude about mummies has come full circle. As mentioned last episode, the Egyptians venerated mummies, treated them as akin to gods. Then their empire collapsed, and people started using their mummies to make paper and paint, grinding them up into mulch, selling them as souvenirs. They desecrated them.

But nowadays, we’ve swung somewhat back toward the Egyptian ideal. We don’t fill mummies with the same supernatural longings, obviously, but we put them on pedestals, gawk at them behind glass, and take great pains to preserve them. We hold them in the awe that their makers knew they deserved.