In this episode of The Disappearing Spoon, Sam Kean talks about memory fugues, a psychological disorder that wipes out biographical information from people’s brains. It is estimated that roughly 1 in 100,000 people seeking help for mental disorders have them. This disorder happens worldwide and it usually afflicts people in their 20s. Scientists have only recently started to piece together what is going on in the brains of those impaired by it.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

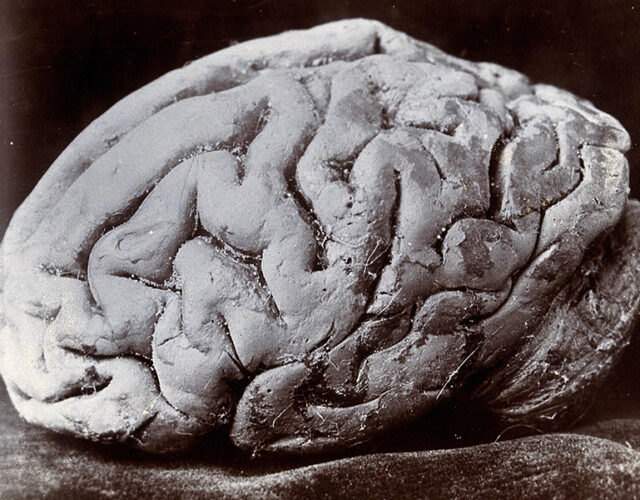

Photo: Wellcome Collection

Transcript

In January 1887, a scrawny, 60-year-old carpenter left his home in Rhode Island on a mission. Ansel Bourne had a Derby hat on his head, and over $500 cash in his pocket. With that money, he was going to buy himself a farm.

He first stopped at his nephew’s store in Providence. Then he stabled his horse and visited his sister in town. After parting with her, he walked on.

But then something strange happened. On the corner of Dorrance and Broad Streets in town, a freight wagon suddenly crossed Bourne’s path. And by the time it left the intersection, Ansel Bourne had vanished.

A few days later, his family posted a missing-person notice in the local newspaper. It described Bourne as an ex-preacher with grey hair and a scraggly grey beard.

The notice also described Bourne as, quote, prone “to attacks of a peculiar kind, which rendered him temporarily insensible.” Basically, Bourne had amnesic fits. He would start walking somewhere a block or two away—and would suddenly wake up three miles distant, having no idea how he’d gotten there. He also suffered from “fainting fits,” probably a euphemism for seizures.

Still, the attacks never lasted long. And Bourne had certainly never vanished entirely. His horse remained stabled for three weeks while his family searched. Eventually his nephew and sister swallowed hard and admitted what must have happened. With all that money on him, no doubt some drifter had attacked him and taken his life.

And in a topsy-turvy way, the family was right. The same day Ansel Bourne disappeared, a drifter calling himself Albert Brown took a carriage from Providence to Pawtucket, then hopped a train to New York. He stayed a few days there in a hotel.

Two weeks later, Brown wandered down to Norristown, Pennsylvania, twenty miles outside Philadelphia. He rented a room in the boardinghouse of a man named Pinkston Earle.

Brown installed some furniture, divided his room into two with curtains, and opened a store in the front half. He sold candy, toys, nuts, and dime goods. His biggest seller was toffee. Some locals found Brown peculiar to talk to—he wasn’t quite all there. But most ignored him. He kept to himself, usually cooking steak or ham in his back room for dinner.

No one really talked to Brown, and they certainly didn’t ask him about Ansel Bourne. But if they had, they would have learned some peculiar things. Like the fact that Bourne and Brown shared a birthday—July 8th, 1826.

Brown’s wife had also died the same day as Bourne’s first wife. And like Bourne the ex-preacher, Brown had studied theology, and had grey hair and a scraggly grey beard.

As you’ve probably guessed by now, this man Albert Brown was in fact Ansel Bourne. But this wasn’t an alias or a scam. Not even Ansel Bourne realized who he was anymore.

That’s because Bourne was suffering from something called a memory fugue—a bizarre psychological disorder that wipes out people’s autobiographical memories.

In short, these people are real-life zombies. As we’ll see, they can still function in daily life. But they have no inner life, no soul. And it’s only recently that scientists have started to understand what on earth is going on inside their brains.

Psychologists don’t know how common memory fugues are. But one estimate holds that roughly one in a hundred thousand people seeking help for mental disorders have them.

Fugues appear in cultures worldwide, and that they usually strike people in their twenties or thirties.

There are two main symptoms of fugues. First, people suddenly feel their inner self dissolving away. Second, people feel an overpowering urge to flee their lives. Let’s look at each symptom in turn.

The dissolving of the self happens fairly quickly, maybe over a minute or two. And people know it’s happening—a sort of premonition or aura. One victim I talked to had time to say “stop” to herself, and she struggled hard to retain her identity. But it dissolved anyway, until she forgot who she was.

These breaks are usually triggered by stress. With the woman I just mentioned, she’d been at dinner with her son and the son’s boyfriend. During the meal, the son mentioned some private details about the woman’s father, who was a violent alcoholic who’d nearly killed her mother.

The woman considered those details a family secret. And she felt hurt and betrayed when the son mentioned them. This caused her to snap, and she lost herself.

The stress facing Ansel Bourne from Rhode Island was theological. As a young man he’d been a flagrant atheist. He even gambled and played cards on Sunday just to spite the Lord.

But one Sunday he hallucinated a voice from the clouds. It asked him to attend chapel. Bourne sneered at the very idea. I’d rather be struck deaf, dumb, and blind, he said. A minute later he got his wish. God struck him blind, deaf, and mute.

After a harrowing few days, God restored Bourne’s senses. And Bourne was so awestruck and thankful that he dedicated his life to preaching the gospel. He spent several decades roaming around and testifying.

But then Bourne married. This was his second wife, his first having died years before. And his new wife demanded that he stop traveling so much for health reasons; he was running himself ragged. Bourne did so, but the guilt of stopping—of neglecting his duty to preach—precipitated his crisis.

Other fugue victims also experience severe stress before their breaks. Most often this is a result of violence or severe financial strain.

And this stress seems to explain the biological basis of fugues. Stress can flood the brain with hormones called glucocorticoids. This flood of hormones then results in a so-called a “neurotoxicity cascade.”

In short, this cascade overwhelms certain structures in the brain—including the hippocampus, which is crucial for storing and retrieving memories.

But it’s not just the hippocampus. Memory doesn’t reside in one single spot in the brain. Many different parts work together to produce memories. And a neurotoxicity cascade seems to disrupt the crosstalk between those different parts. The result is amnesia.

Overall, some psychologists view fugues as a defense mechanism. They’re a mental “circuit breaker.” Just like an electrical circuit breaker protects your home from surges of electricity, the fugue mental circuit breaker protects people from severe stress by shutting memory networks down. Afterward, the self dissolves, and people no longer know who they are.

And after the self dissolves, the second symptom takes over—the desire to flee. The word fugue actually means “flight.”

The initial dissolving of the self can be scary for fugue victims. But the desire to flee is often happy, even euphoric. That’s because, by fleeing, people feel like they’re leaving all their problems behind. They’re totally free now, and they enter a sort of manic state.

They usually have boundless energy, too. And they burn that energy off by staying in constant motion. Some fugue victims walk for hundreds of miles at a stretch, and get huge blood blisters on their feet. Others suffer terrible sunburns. But they don’t notice or care. They’re just so happy to be free.

Some victims come back to themselves within days or weeks. Other fugues last for years, even decades. And while some victims never leave town, others flee to entirely different countries—in cars and boats, on bicycles and trains. A few have crossed whole oceans.

One woman in New Zealand finally had to put a wildlife tracking collar on her husband—the kind that biologists use to track migratory birds and mammals. She’d seen one in a nature documentary, and whenever her husband fled after that, she’d simply get online and track him down.

The most famous fugue victim in history is probably a fictional character—Jason Bourne of The Bourne Identity books and movies. Jason is of course named after Ansel Bourne.

But other fugue cases have popped up in the news. And a closer look at those cases can reveal some interesting things about how memory works inside our brains.

In 2008 a ferryboat captain near Staten Island spotted some brown hair bobbing in the water. He hurried over and pulled out a twenty-three-year-old New York schoolteacher named Hannah Upp.

After being rescue, Upp had no idea who she was or why she’d been swimming. At the hospital, she was then confused as to why her family seemed so happy to see her. They explained she’d been missing for three weeks.

Using security cameras around New York, police later tracked Upp’s movements during her fugue. Remarkably, she’d purchased coffee at Starbucks; showered at her gym; and logged onto her email account at an Apple store. But if Upp couldn’t remember something as basic as her name, how could she remember how to order coffee or check email?

The solution to this mystery lies in the fact that our brains actually contain different types of memory. One type is called semantic memory.

Semantic memories involve basic facts about the world and how it works. For example, that Abraham Lincoln was the 16th president, or that Starbucks sells coffee. There’s nothing personal about these memories. They’re just facts

There are also muscle memories, which involve physical actions. Like riding a bike or signing your name.

These types of memories can overlap, but the key point is that each one relies on distinct brain circuits. So you can lose one without losing the others. And this distinction between different types of memory helps shed light on what happened to Hannah Upp.

Although she’d forgotten herself, she could still order coffee and do other routine tasks. That’s because the fugue had left her semantic and muscle memories intact. I mean, how often do we sign our name or type in our passwords without really thinking about what we’re doing?

On the other hand, personal memories meant nothing to her. For instance, when Upp read the messages in her inbox, several were begging to know where she was. But they simply didn’t register with her. Other fugue victims forget their pets’ names, or the smell of their newborn children. Some can’t even recognize photos of themselves.

Unfortunately, there’s no standard treatment for fugues. Therapists have tried hypnosis, electroshock therapy, and drugs, all to no avail. Sometimes patients snap out of them without any treatment at all.

That was the case with Ansel Bourne. Remember that he’d moved from Rhode Island to Pennsylvania. He was living there as Albert Brown and selling candy.

Well, one morning at 5am, Brown heard a bang! like a pistol firing. He started awake—and was suddenly Ansel Bourne again. The bed felt alien to Bourne, with a ridge digging into his back. He then noticed electric lights outside—and realized that he’d somehow fallen asleep in a stranger’s room.

Bourne was terrified. Would the stranger be home soon? Would they beat him bloody? He huddled beneath the covers, waiting for the occupant—or the police—to barge in.

After two hours, he finally peeked into the hallway. Then he crept down the hall and risked knocking at someone’s door.

It happened to be his landlord, Pinkston Earle. Bourne asked Earle what day it was.

“The 14th,” Earle replied.

Bourne was baffled. “Does time run backward here?,” he asked. “When I left home it was the 17th.”

“The 17th of what?”, Earle said.

Bourne said, “Seventeenth of January.”

Now Earle was baffled. He said, “It is the 14th of March.”

Bourne gasped.

By this point, Pinkston Earle was thinking his tenant had gone soft in the head. So he summoned a local doctor. But under questioning, Bourne insisted he wasn’t Albert Brown. The doctor soon sent a telegram to Bourne’s family, who had long given him up for dead. A few days later, they were reunited. All in all, a fairly happy ending.

Unfortunately, not all fugue cases end so happily. After the teacher Hannah Upp vanished in New York City, she moved to Maryland, where she disappeared again in 2013. Police located her that time. But then she took a job at a Montessori school on the island of St. Thomas in the Caribbean.

In 2017, Hurricane Irma swept across St. Thomas and devastated it. Shortly afterward, Upp went swimming one morning and never returned. A construction crew later found her clothes and keys abandoned on the beach.

No one knows what happened. Perhaps she was swept out to sea or mugged. But given her history, it’s more than possible that the stress and devastation of the storm ignited another fugue. Friends of Upp’s plastered St. Thomas with posters of her—both to alert others and to possibly jog her own memory, in case she recognized herself. But Hannah never turned up.

Despite several well-documented cases, some psychologists do not believe in fugues. One red flag is the fact that fugue victims can easily form new memories. That doesn’t normally happen with amnesia, since most amnesiacs cannot form new memories. Also, regular amnesiacs almost never recover lost memories. But fugue victims can, which raises suspicions.

Instead, these psychologists suspect that fugues are an elaborate deception. And to be fair, people have been caught faking fugues in the past to get out of crimes and debts.

But most psychologists argue that, however rare, fugues are real. In fact, some psychologists see fugues as extensions of the sort of temporary, everyday amnesia we’ve all experienced before. Think of sleepwalking, or an alcoholic brownout, or intense daydreaming. Or even those times when we’re so absorbed in something we miss our bus stop or exit on the highway. Fugues are more extreme, obviously. But perhaps we all have a capacity for fugues buried inside us.

If nothing else, this strange disorder provides a glimpse of how our brains produce our sense of self—and of just how scarily fragile that essential part of us can be.