Today we take Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity—E=mc2—as a given, but it was wildly controversial when it was proposed in 1915. Which is why one of his admirers went to great lengths to prove him right.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

Arthur Eddington could only look up at the clouds and sigh.

That month, May 1919, was a time of both elation and frustration for Eddington. He was on the island of Príncipe off Africa, four thousand miles from his home in England. He’d come there to photograph a solar eclipse—a project that would serve as a crucial test of Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Which was exciting. Eddington believed passionately in relativity, and wanted to give the theory a boost. Still, so much had gone wrong. The humid, dripping weather on Príncipe had been hell on the telescopes and cameras. Then monkeys started stealing their equipment and disappearing into the jungle.

Worst of all was the clouds. Every stinking day there were clouds. Which obviously wasn’t ideal for photographing the sky.

On the day of the eclipse, clouds blocked the sky completely. Eddington could only gaze up and despair. Not only was this ruining his change to confirm relativity, but if he failed, he could face serious repercussions back in England. In fact, the only reason he wasn’t in prison then was because he’d promised to photograph this eclipse.

But at the height of his misery, as if moved by the hand of God, the clouds suddenly parted. Eddington didn’t even have to time to rejoice. He pounced on his equipment and started taking photographs. He was moving so fast, he had no idea whether they would turn out—and no idea what he’d do if they didn’t.

In 1915, Albert Einstein proposed his theory of general relativity. It aimed to overthrow the laws of Isaac Newton.

Einstein’s theory was wildly controversial, and no wonder. Put yourself in the mind of someone back then. Newton basically invented science as we know it. He did fundamental work on light, gravity, and motion. He also figured out how to fuse math and science together. He was the greatest scientist in history. Now this Einstein fella says he can do better? Come on.

Einstein was aware of this skepticism. So, he proposed some do-or-die tests. Tests that would definitively prove or disprove his theory. One involved how gravity could bend light.

That might sound odd, gravity bending light. But according to Einstein, E=mc2. That is, energy has some mass. Light is energy, so light has mass. And if something has mass, gravity will tug on it.

So imagine a ray of light from a distant star. If its path strays near our Sun, the Sun will tug on it and deflect it. It’s like a bullet zipping past a giant magnet. The straight path bends.

The test Einstein proposed involved measuring that bend. Imagine some stars in space. They emit light that streams toward Earth. So when you look up at night, you can see those stars in certain positions in the sky.

Now imagine those same stars, but in a patch of sky near the Sun. The stars still emit light that streams toward Earth. But this time, the Sun bends the light before it reaches Earth. So each star now appears shifted to a slightly different spot in the sky.

Normally, it’s impossible to see those shifts because the sheer brightness of the Sun overwhelms every other star in the sky. But during an eclipse, the Sun dims. Suddenly you can see the stars in their new, shifted positions.

Now, there is one nuance here. Isaac Newton’s theory also predicted that gravity would bend light. Newton thought of light as a stream of tiny particles. And he once proposed, in passing, that gravity could bend light particles.

Crucially, though, Newton’s theory and Einstein’s theory made different predictions about the degree of bending. Einstein’s theory predicted twice as much bending.

So that was the test Einstein proposed. Photograph some stars in the sky at night, to determine their true positions. Then photograph those same stars during an eclipse when they’re right near the Sun. Finally, superimpose the two images on top of each other; then measure the deflection of starlight by the Sun’s gravity. If the deflection was one value, Newton was right. If the deflection was twice that value, Einstein was right. Easy-peasy.

Except, things weren’t easy at all, given the state of the world then.

Einstein was German. And most of the world despised Germany for starting World War I. It didn’t matter that Einstein hated the warmongering German government and later renounced his German citizenship. To outsiders, especially in England, Einstein was a dirty Teuton, and that was that.

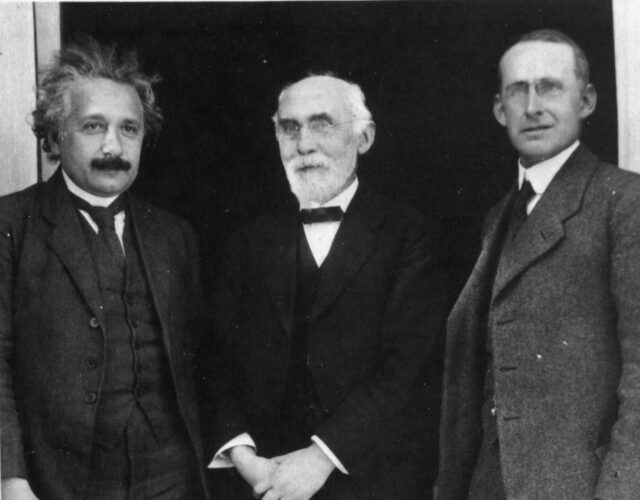

But there was one English scientist who didn’t despise Einstein—Arthur Eddington.

Eddington was classic English eccentric. He lived with his sister Winifred his whole adult life, never even trying to marry. He believed that all matter in the universe was conscious and could think. And not just living things like animals, but cars and thumbtacks and fingernail clippings, everything was conscious. He also dabbled in numerology. In cloakrooms, he insisted on hanging his hat on peg 137, because that number often arose in his equations.

Frankly, Eddington had something of a man-crush on Einstein. He worshipped Einstein as the greatest scientist of the age. He wasn’t wrong, obviously. But Eddington believed in Einstein’s theory largely because he found it so beautiful. Eddington felt that no theory so elegant could possibly be wrong.

Eddington supported Einstein for political reasons as well. Eddington was raised a Quaker, and he was a committed pacifist. As such, he became a conscientious objector during World War I and refused to serve in the army.

This was not a popular stance. Conscientious objectors in England had to wear armbands in public, a tactic to shame them. Many were thrown in prison, too. Eddington himself failed jail time.

Einstein was a pacifist as well, and he faced just as much ridicule at home. That was another reason Eddington admired him and felt a kinship. Furthermore, Eddington wanted to heal the world after the war. And he thought that an English scientist confirming a German scientist’s theory might help both sides bury their grievances and forget the brutality of the Great War.

But again, supporting a German scientist was deeply unpopular. Especially when that German was trying to overthrow the ideas of one of the greatest Englishman of all, Isaac Newton.

During one debate about Einstein’s theory, a member of the Royal Society scientific club in London pointed to a portrait of Newton hanging on the wall. He fumed, “We owe it to that great man to proceed very carefully.” In other words, Watch out, Albert.

Another English scientist even claimed that the threat of Einstein’s relativity was every bit as bad as the sinking of the Lusitania. Which, for context, killed 1200 people! Talk about hyperbole.

Still, some British scientists agreed with Eddington. They thought that confirming Einstein’s theory might be good for postwar relations. They also made a sly calculation. If Einstein was right, he was going to be proved right by someone at some point. And that someone might as well be English.

So in 1917 they hatched a plan. Again, Eddington faced hard prison time as a conscientious objector. So a few well-placed colleagues called some political friends. They proposed that Eddington be spared jailtime—on the condition that he observe the upcoming eclipse in 1919 and test Einstein’s theory. Photographing the eclipse was Eddington’s get-out-of-jail-free card.

During the May 1919 eclipse, the sun would appear in the sky near a cluster of stars called the Hyades . On a cosmic scale, they’re pretty close to Earth—just 153 light-years away, a mere 900 trillion miles. The Hyades appear in the constellation Taurus. There’s lots of stars in the cluster, and they’re quite bright. This gave Eddington lots of possible stars to measure the bending of light due to gravity.

The eclipse started in Peru and arced across the Atlantic Ocean toward Mozambique in Africa. Eddington’s destination, the island of Príncipe, sat in the ocean 110 miles west of Africa. The island was an old Portuguese coffee and cocoa colony.

For Eddington, the upside to doing observations in Príncipe was its relative proximity to Europe. The downside was the frequent cloud cover, which could scotch the mission. So Eddington arranged for a second, backup mission to observe the eclipse in northwest Brazil. The Príncipe mission planned to use a 13-inch telescope. The backup Brazil mission would have another 13-incher, plus a 4-incher as a double-backup. The telescopes would focus their light onto photographic plates to capture permanent images of the stars.

The accommodations in Brazil turned out to be pretty posh. The government there granted the astronomers access to Brazil’s first automobile, to help move equipment. The government also gave them an ice machine. Pretty fancy.

Things in Príncipe were more rugged. Eddington’s headquarters was an abandoned plantation on the edge of a tropical jungle. <MONKEYS> The jungle was home to a clan of rowdy monkeys. Which the Englishman found funny at first. Who doesn’t love a rowdy monkey?

But these monkeys were too rowdy. While Eddington and his assistants were setting up their equipment, the monkeys would dash up, grab some vital part, and sprint back to the jungle. The Brits in their stuffy suits would have to race after them. They usually recovered the equipment, but not always. The monkeyshines quickly got irritating.

The morning of the eclipse dawned cloudy, and stayed cloudy. During the eclipse itself, the world dimmed right on schedule, but Eddington couldn’t see a damn thing. He could only groan, and hope things were going better in Brazil.

Halfway through the eclipse, though, around 2pm, the clouds broke. In the darkness, Eddington scrambled to take pictures. Originally, he’d been hoping for several dozen. In the end he got 16. Not great, but not a disaster.

At least not at first. After Eddington sailed back to England, he developed the photographic plates. The results were not good. Of his 16 images, only two had enough stars to be useful. Now, the deflection of light on those images did support Einstein’s theory over Newton’s. But two images was a shaky foundation for a revolution. He would just have to wait to hear from Brazil and hope for better news.

Unfortunately, he waited quite a while. Given the primitive state of travel and communications then, Eddington sat and stewed until October before he heard results from Brazil. Five bloody months! And what he heard was more bad news.

As a small ocean island, Príncipe had quite consistent temperatures. Even during the eclipse, when the sun was blocked, the temperature dipped only a few degrees.

That was not the case in Brazil. The Brazil site was situated far inland. And when the eclipse blocked the sun, the temperature dropped hard and fast. That was a problem, because the 13-inch telescope there had parts made of metal that expanded in heat and contracted in cold.

So when the temp dropped, those metal parts contracted and warped. It wasn’t a lot. But it was enough to ruin the images of the stars. Instead of sharp pinpoints of light, the images were smeared. That made the pictures were all but useless. Eddington moaned. Would nothing go right?

Thankfully, the 4-inch telescope in Brazil—the double-backup—had come through. Because that telescope was far smaller, the contraction of its metal parts had been smaller, too. Which meant less distortion. As a result, the images of the stars came through beautifully—nice and sharp. And when the deflection was measured, it matched Einstein’s predictions to a T. Eddington finally had his evidence.

Last episode we heard how Einstein investigated the anomalous orbit of Mercury. He said something snapped inside him during the golden moment when his theory proved correct. Eddington experienced a similar elation when the eclipse results came through. A surge of emotion, a flood of endorphins. He had just overthrown Isaac Newton. Eddington called it the greatest moment of his life.

And the public shared his enthusiasm. When Eddington announced the eclipse results in November 1919, newspapers in London and New York ran delirious headlines. Like: “Revolution in Science.” “Lights all askew in the heavens. Men of science more or less agog.” What a great word, agog. Anyway, overnight Einstein became a worldwide celebrity, the most famous scientist in the world.

And it’s easy to see why. Eclipses are inherently dramatic. Since ancient times they’ve been taken as signs of big things. Wars, assassinations, disasters—and revolutions.

Einstein himself, and his personality, also made the story fun. Here was a frumpy-haired, loveable mensch with a great sense of humor. After the eclipse announcement, a reporter asked Einstein how he would have felt if the results had not supported his theory. Einstein said, “I would feel sorry for the dear Lord. The theory is correct.”

Beyond the eclipse itself, the story caught fire because the world simply needed good news after five years of ugly war. Einstein gave people something to celebrate. He also provided hope for future reconciliation. As one writer put it, “A new theory of the universe, the brainchild of a German Jew working in Berlin, was confirmed by an English Quaker on a small African island.”

Philosophers were agog as well. One later held up Einstein and the 1919 eclipse expedition as the best example he’d ever seen of how science should work. Einstein had developed a new theory of nature. He’d then proposed specific ways to test his theory with experiments—experiments whose results would either support his theory, or prove it wrong. There was nothing muddled or ambiguous here. Einstein made clear predictions, and the experiments gave clear yes-no answers. It was perfect science, and Einstein deserved his fame.

Einstein himself, however, was mostly bemused by this fame. After all, he was a physicist, dealing with obscure things like the curvature of space-time. Why did people care?

But people couldn’t get enough. His name and likeness appeared in movies, pop songs, radio jingles. He landed on the cover of Timemagazine. He attended movie premiers with Charlie Chaplain, and marched in the Rose Bowl parade. The constant attention bewildered Einstein, but he mostly enjoyed himself. And it all started with the 1919 eclipse.

Other people, however, did not enjoy Einstein’s fame. Within Germany especially, many people resented him—in part because he was Jewish. They called Einstein dirty slurs. And they smeared relativity itself as, ugly quote here, “Jew science.” Jew science was supposedly unnatural—too abstract and counterintuitive. Unlike the safe Teutonic science of Newton. Einstein’s enemies also conflated scientific relativity with moral relativism. Which to them made Einstein an enemy of all things decent.

This wasn’t just name-calling, either. On two separate occasions, thugs broke into Einstein’s apartment in Berlin and ransacked it. He also appeared on a list of Jews that far-right figures wanted to assassinate.

Even among those who didn’t want to kill Einstein, many scientists still didn’t buy his theory of relativity—despite Eddington’s results. Convincing these skeptics would require even more heroic efforts, by yet another oddball scientist. This scientist would test relativity by ascending to record elevations in what amounted to a giant beer keg. And he would thereby inspire a generational hero for all science nerds. All that and more next week.