The so-called “Peking Man” fossils are some of the first ancient human remains discovered in mainland Asia. So when they disappeared during World War II, it was called one of the worst disasters in the history of archaeology. Now some archeologists claim to have tracked them down. The only problem is they’re underneath a parking lot.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Original Music by Jonathan Pfeffer:

- Wang Fan – Zero (from An Anthology of Chinese Experimental Music 1992-2008)

- Listening to the Pine-trees (from Chine / Musique Classique)

- Sarah Hennies – Fleas

- Wang Changcun – Through the Tide of Faces (from An Anthology of Chinese Experimental Music 1992-2008)

- Zhegu Fei (The Partridge) (from Chine / Musique Classique)

- All other music composed by Jonathan Pfeffer

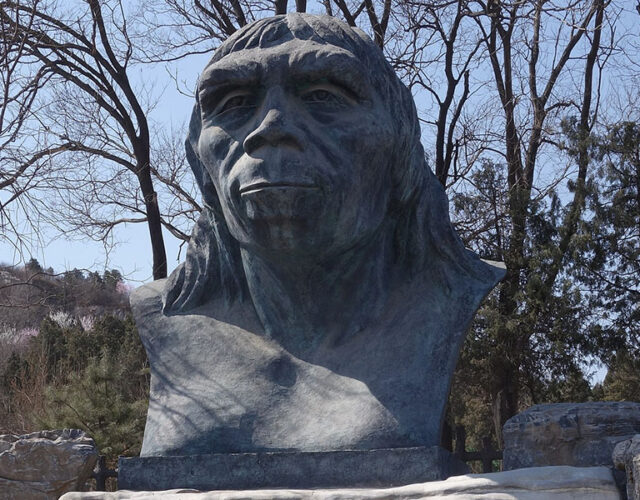

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Transcript

As soon as Wenzhong Pei saw the bone, his heart began to race. It was the most spectacular fossil that he—or for that matter, the entire world—had ever seen. An ancient human skull. Little did Pei know that this prized skull would soon become the heart of perhaps the greatest mystery in all of science.

The year was 1929. Pei was excavating in a limestone cave 30 miles southwest of Beijing. The area had long been famous for fossils, with bones just sticking out of the cliff sides. Locals called the area Dragon Bone Hill.

Scientists like Pei classified the bones a bit differently—as hyenas and stags; as rhinoceroses and beavers and saber-tooth cats. And, most spectacular of all, as ancient humans.

That first skull was cracked, and was embedded in sand and rock, and was discolored with dirt after half a million years underground. But to Pei, it was nevertheless beautiful. And along with other human bones from the cave, it would soon become famous as Peking Man—the first ancient humans ever discovered in mainland Asia.

So where are these world-historic fossils today? We have no idea. That part of China was soon overrun with war. And in the chaos that followed—poof—these priceless fossils disappeared. It’s been called the worst disaster in the history of archaeology.

Scientists have spent the last 80 years searching for Peking Man, hunting down wild rumors across the globe. Not a single fragment has turned up. In fact, it’s only within the past decade that maybe—just maybe—we’ve uncovered the first real clues for solving one of the greatest mysteries in all of science.

From the Science History Institute, this is Sam Kean and the Disappearing Spoon – a topsy-turvy, science-y history podcast. Where footnotes become the real story.

There’s an old joke about the Holy Roman Empire that it was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.

Peking Man’s name is a little like that. Peking is an outdated name for Beijing. And the Peking Man unearthed in that limestone cave was actually a mess of bones from roughly forty men, women, and children. For historical continuity, I’ll call them the Peking Man fossils, but there was a lot more there than one male.

Anatomically, the Peking people had wide noses and weak chins. They stood around five feet tall, with longer arms than humans today—remnants of their, our, tree-swinging past.

Today, we classify Peking Man as Homo erectus. The human family tree is messy, but different populations of Homo erectus on different continents gave rise to both modern human beings and to human offshoots like Neanderthals.

The Peking Homo erectus also had fairly big brains—nearly as big as our brains today. And that’s why the Peking Man fossils are so important. The bones were exceptionally well-preserved, and they came from a crucial transition point in history—when hominid intelligence was exploding.

The Peking bones were discovered amid sophisticated stone tools like axes and chisels and hammers, and the cave shows signs of controlled fire use. So they probably hunted and cooked. They also appeared to live in tight-knit communities. All in all, they were strikingly modern.

At least we think so. More than any other field, archaeology depends on reinterpreting old specimens in light of new evidence. Peking Man lived during a critical time in hominid evolution, and scientists would kill to be able to study those bones with new technologies. But all that remains of Peking Man are some plaster casts and drawings.

So what happened to them?

The bones’ disappearance starts in 1941. At that time, Chinese, European, and American archaeologists were all excavating around Dragon Bone Hill. But Chinese scientists like Wenzhong Pei were getting nervous.

Imperial Japan had been running amok in China for years by then, committing horrible atrocities. A full-scale invasion seemed likely.

And the scientists knew that the Japanese coveted the Peking Man fossils. Imperial powers have always stolen the cultural treasures of the people they conquered. Look at how Europeans ransacked Greece and Egypt. Similarly, Japanese scientists coveted the Peking Man fossils as war booty.

To protect the Peking bones, the scientists in China hid them in a safe. But even that didn’t seem safe enough. So in 1941 Chinese archaeologists begged their American colleagues to take the fossils to the United States for safekeeping, rather than let them fall into enemy hands. Although reluctant, the Americans agreed to help.

First, the Americans reached out to the U.S. ambassador to China. They tried convincing him to hide the bones in his luggage as diplomatic material and smuggle them out. But the ambassador refused to get involved.

So the scientists turned to the U.S. military. First, they smuggled out some plaster casts of the bones. Finally, in November 1941, the scientists began wrapping the bones themselves in cotton and packing them in two military footlockers.

Based on eyewitness accounts the footlockers were transferred to a U.S. Marine base outside Beijing. Then they were shipped via train to another marine base in Qinhuangdao along the coast. This coastal base was called Camp Holcomb.

The bones arrived at Camp Holcomb in early December, and the plan was to evacuate them the following Monday. A ship was arriving from Manila that day, the SS President Harrison.

Unfortunately, the President Harrison’s journey was even briefer than its namesake’s term in the White House. You see, the Monday for shipping the bones out was Monday, December 8th—the day after Pearl Harbor. And before the President Harrison could reach China, Japanese ships swarmed and attacked her. She ran aground, leaving the Marines at Camp Holcomb stranded—along with the fossils.

And here’s where things get murky. As predicated, Japan invaded China. And Japanese scientists invaded the lab where the fossils were kept cracking open the safe. They were furious to find the bones missing. They arrested an American associated with the lab and interrogated him for five days about the fossils’ location.

Meanwhile, the fossils themselves were stranded at Camp Holcomb in Qinhuangdao. During the invasion, many Marines there were taken prisoner and their belongings ransacked. And in the chaos, the fossils disappeared.

Unfortunately, Beijing was a black hole during World War II, with few messages going in or out. Then, to make things extra confusing, a civil war broke out in China in 1945, pitting rebel Communists against the Nationalist government. So even after World War II ended, China was in turmoil.

The Communists finally won the civil war in 1949, and things calmed down. But eight tumultuous years had passed since anyone had seen the Peking Man fossils. Their whereabouts were a complete mystery.

That didn’t stop rumors from swirling, of course. The most common rumor held that the marines at Camp Holcomb had buried the footlockers for safekeeping. But other rumors held that Japanese soldiers had found the bones and dumped them outside as garbage. Or hell, who knows, maybe they’d used them as target practice. Soldiers aren’t exactly known for sensitivity.

Then there were the wild rumors. That the bones had been smuggled to Yalta on Russian ships. Or seized by Chinese Nationalist forces and taken to Taiwan. And on and on.

Pretty soon shady characters were offering million-dollar ransoms to return the bones—an obvious scam. But both the FBI and CIA got involved tracking down leads. One scientist even fielded a phone call from a professional psychic who had once used dowsing rods to hunt for Bigfoot in Maine. She figured that some old hominid bones couldn’t be much different. And the poor scientist—out of sheer desperation—gave her a shot. Amazingly, it didn’t work.

Poignantly, after decades of fruitless searching, some of the original caretakers of the fossils began to wish they’d just let the Japanese take them in 1941. At least the bones would have been well cared-for, instead of disappearing for good.

Still, a few scientists never gave up. Some were born long after the bones disappeared, but grew obsessed with tracking them down. And in 2010 one of them got the first real lead since World War II when an email arrived in his inbox.

The message told the story of Richard Bowen, a marine corporal who had been stationed at Camp Holcomb. But Bowen wasn’t stationed there when the fossils first arrived. Bowen was stationed there in 1947, when American troops were still occupying some previously Japanese-held territory in China.

In 1947, the civil war between the Communists and Nationalists was at its peak. And Bowen and the 125 marines at Camp Holcomb found themselves right in the thick of things.

The camp was mostly Quonset huts and tents, with one brick building. It sat right on the beach—the place reminded Cpl. Bowen of Cape Cod. Minus the guns. Nationalist ships occupied the nearby harbor, while Communist troops occupied the hills surrounding the beach. This meant that the warring parties were shooting at each other right over the top of Camp Holcomb.

But it didn’t take long for the communists to target the marines themselves.

There wasn’t much to do at Camp Holcomb except visit the bar on base, which served peanuts and warm beer. So one night, probably after knocking some brewskis back, some knucklehead marines snuck off base for some ice. That night’s beer was the last they would enjoy for some time. Communist soldiers immediately seized and arrested them.

There were other ambushes, too. And before long, the communists had surrounded Camp Holcomb.

Soon, the communist leaders marched into camp. They ordered the marines to surrender. They claimed they had a quarter-million troops in the surrounding hills.

The marines looked the communists up and down and smirked. The communists were wearing ragtag denim uniform and were unarmed. Meanwhile, the marines had fancy camouflage uniforms and machine guns. A quarter-million troops. Uh-huh. Obviously the communists were bluffing.

But that night the communists started lighting campfires as a show of force. Just a few at first. Then more. And more. And more. Soon the whole hillside was ablaze. Richard Bowen said it looked like the world’s biggest Christmas tree, and he was terrified.

In short, the marines were facing annihilation. And if you want to hear the full story of how they escaped—including the daring rescue of a trapped missionary woman who was nine months pregnant and going into labor—then visit Patreon.com/disappearingspoon. It’s a wild story.

But to keep focused on the Peking Man bones, the marines had to fortify their camp against those quarter-million communist soldiers. So, the marines began digging like crazy. They dug foxholes and trenches and made pits for machine guns. They often dug all night long, then collapsed in exhaustion the next day.

One night a lieutenant asked Bowen to move his machine gun to cover another area. This meant digging another hole first, so Bowen got to work. And halfway through that dark night his shovel hit something solid.

He bent down and squinted in the dark, brushing off the dirt. It was an old Marine footlocker. So he opened it up. Inside he found a bunch of skulls staring at him.

Well, Christ almighty. It was the middle of the night, in a hostile land, with communists strafing him from the hillsides. Skulls were the last thing Bowen wanted to see right then. So he reburied the footlocker, and moved on to dig elsewhere.

Now, as I explain on Patreon, the marines did escape the base—barely. But once he was back home in America, Bowen kept wondering about those bones. Where had they come from? Why were they there?

A quarter century would pass before he got an answer. Here’s an online interview with Bowen…

Richard Bowen: I didn’t know anything about, that there was anything such as Peking Man or Peking Man bones or anything like that. Except for 20- 25 years ago, I saw on TV, a show in which he said the picky man bones were brought down from Peking by two Marines. The Marines were captured in Qinhuangdao tower that sort of, gee whiz.

Sam Kean: And naturally, Bowen began to wonder. Could the bones he’d seen at Camp Holcomb be Peking Man? He later told this story to his son Paul. And just in case there was something there, Paul emailed an archaeologist out of the blue.

The archaeologist was stunned. He consulted military records, and Bowen’s story checked out. So the archaeologist got in touch with two Chinese colleagues and arranged to visit the old Camp Holcomb site to see if anything—anything—might be salvaged.

A few months later, the archaeologists found themselves in northeast China. They secured an elderly local man named Wang to serve as their guide. Wang actually remembered the marine base from 70 years earlier—he said the Americans had treated him well as a boy. And yes, he knew right where the spot was. They hurried off.

Had the decades-old mystery of Peking Man finally been solved? It seemed too good to be true.

And of course, it was. The scientists arrived at the old Camp Holcomb … … and found a parking lot, surrounded by warehouses. The area had been developed for industry. There was nothing to do but stare.

But unlike every other dead end in this quest, this lead isn’t completely dead yet. The parking lot and warehouses are slated for redevelopment soon, and cultural agencies in China are keenly aware of the possibility of recovering Peking Man. The solution to one of the greatest mysteries in all of science might lie no deeper down than a Chicago pothole.

I mean, sure, it’s a longshot that the bones survived. But hope costs nothing. And the alternative—that these fossils, who were witnesses to some of the most important changes in the history of humankind, got destroyed because of stupidity and carelessness—well, that’s just too awful to think about.

And the truth is, these bones have already overcome astronomical odds twice before. First, in getting fossilized at all, a rare thing. Then in being discovered the first time, in one remote cave on the vast surface of the Earth.

So I have to think that luck is on the side of the Peking Men, Women, and Children. If the fossils really are beneath that parking lot, then after five-hundred millennia of waiting, well, I’m willing to be as patient as they were—and try one more time to bring them back to life.

This is the Disappearing Spoon podcast, brought to you by the Science History Institute. Find out more about their library, museum, and multimedia magazine at sciencehistory.org.

Make sure you check out the Science History Institute’s other awesome podcast, Distillations. You can find their in-depth narrative stories and interviews about everything from Space Junk to Sex, Drugs, and Migraines anywhere you get your podcasts, and on their website: Distillations.org.

You can find more incredible stories from my books at samkean.com. You can also book me as a speaker at your school or event.

If you like this podcast, please support it at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. It costs as little as seven cents per day. You can also get bonus episodes and signed books.

Please spread the word to others as well, and subscribe in iTunes, Stitcher, or other places.

This episode was written by me–Sam Kean. It was mixed by Jonathan Pfeffer, and produced by Mariel Carr and Rigoberto Hernandez.

Thanks for listening…