Justus von Liebig was the most famous chemist in the world in the mid-1800s, but his reputation quickly soured when he created a deadly baby formula.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineering: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

In the 1850s, the world’s foremost chemist moved next door to one of the world’s foremost scholars of classical history. They instantly hated each other.

That chemist, Justus von Liebig, thought that memorizing Greek and Latin odes and studying dead civilizations was a stupid waste of time. It was so impractical—how did it help humankind?

Liebig belonged to a generation of German scientists who were remaking the world—better living through chemistry. He mocked his ivory-tower neighbor as passé and ridiculous.

Still, life has a way of playing jokes on people. Liebig had a daughter named Johanna, and the classics scholar had a handsome son. Guess what? They fell in love.

Johanna was Liebig’s favorite daughter. She seemed smitten. And the son was at least a doctor and somewhat scientific. So Liebig sighed, and grudgingly approved the marriage. How could he deny his Johanna happiness?

And Johanna was happy. Mostly. She had six children with her husband, but struggled with one aspect of motherhood. She couldn’t produce enough milk to breastfeed. She struggled especially with her daughter Carolina in 1864. Her little baby was constantly hungry—even slightly starving.

It broke Liebig’s heart. So, he decided to solve the problem through chemistry. He began developing artificial milk—one of the first baby formulas in history.

And it wasn’t just Johanna and Carolina who would benefit. Liebig realized that artificial milk could help millions of women who struggled to breastfeed. It could perhaps even end the scourge of infant malnutrition across the globe. How noble.

Liebig got right to work. Little did he know that his noble idea would provoke an international scandal. And far from saving lives, would actually kill several innocent babies.

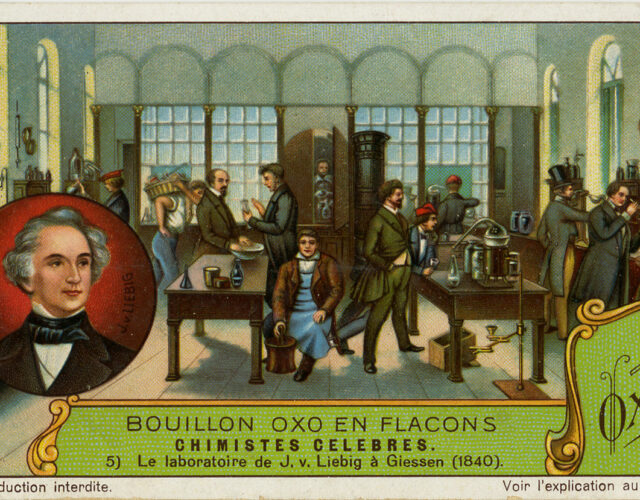

In his time, everyone knew what Justus von Liebig looked like: a beaked nose, a big balding forehead, and grey hair swept back like he’d just been caught in a gale. People knew his mug because Liebig was arguably the most famous scientist alive. He was certainly the most overexposed.

He was born in 1803 near Frankfurt. His father ran a dry-goods store and made drugs and dyes as a side hustle. After years of home study, Liebig attended university to learn chemistry. But he got mixed up with radical political groups and fled to Paris to avoid arrest. There, he learned chemical theory and lab techniques from the greatest chemists in the world.

But however much he revered French scientists, Liebig grew to disdain French people. And after returning home, he did everything he could to ensure that Germany overtook France as the world’s premier scientific power.

Liebig’s biggest contribution to science was his role in founding organic chemistry, the study of living matter. He made the field far more systematic and rigorous, and vastly improved lab techniques. An analysis that took months before could suddenly be accomplished in days.

Not everyone appreciated him personally. He was vain and quarrelsome, and chain-smoked cigars even in the lab. But no one could deny his influence—nor his impact.

As part of his organic chemistry work, Liebig studied plant nutrition. He proved that crops often struggled to grow due to a lack of nitrogen. Liebig then put this knowledge to use by developing the first artificial fertilizers—or, as people called them then, “chemical manure.”

Chemical manure made Liebig’s name. It was exactly the sort of work he valued: work that improved people’s lives, the opposite of his ivory-tower neighbor. Liebig once declared that “society needs manure more than mathematics.”

Beyond the lab, Liebig published popular books and developed a new fresco technique for painters. He also began spinning off businesses based on his chemical research, hoping to profit off his genius.

Some of these businesses flopped. His instant coffee was reportedly disgusting. His process to make better mirrors failed, too. People’s reflections just didn’t look right; they had a ghastly yellow color.

Apparently, French women especially hated the mirrors. In response, Liebig sneered that he wasn’t surprised. French women were all sallow and sickly anyway, and the mirrors reminded them how ugly they were. It was a shockingly mean thing to say. And eventually, barbs like that would come back to bite him.

Liebig finally hit the bigtime with a product called meat extract. Essentially, he developed a way to render beef into a molasses-y goo—concentrated glop to provide nutrition to poor people.

Shrewdly, Liebig put the recipe in the public domain, so anyone could use it to help people. But he also founded a company to sell the extract, with his famous name attached. That way, he could look like a humanitarian for making the recipe freely available, but also cash in.

The meat-extract idea took a while to succeed. The raw material, the beef, was expensive in Germany. But eventually an entrepreneur in Brazil got in touch. He explained that leather-tanners in South America often skinned their cows for hides, then just dumped the carcasses to rot. The man proposed collecting the bodies for Liebig’s meat goo instead. Liebig loved the idea, and the venture got underway.

To make the extract, they’d cube the cow flesh, pulp it with iron bars, and boil it into a slurry while skimming off anything that rose to the surface. They sold the goop in white bottles with Liebig’s picture emblazoned across the front.

The extract proved wildly popular, especially among doctors and nurses. Florence Nightingale praised it to the skies. One London hospital dished up 12,000 servings per year.

The only country that disdained the extract was France. Liebig took this as another sign of their barbarism. But with so many other countries clamoring for it, the meat extract made money hand over fist. The venture also helped kickstart South America’s famous beef industry.

Soon, Liebig grew rich and important enough to become a baron in Munich. He began embarking on public speaking tours, giving talks that were widely reported in newspapers.

Meanwhile, however, some of Liebig’s colleagues were growing uneasy about his habit of mixing science with business. They hated his endless self-promotion, too.

Now, some of this was just academics getting their undies in a bundle. How dare he run a business. Why, he even had the gall to be good at it! Such complaints look a bit silly nowadays.

But there was legitimate criticism, too. Colleagues worried that his commercial interests might warp his scientific judgment. For instance, could you really believe his claims about the nutritional wonders of meat extract, knowing that he was making money off it? Perhaps—but that should give you pause. Liebig certainly wanted to help humankind. But he sometimes seemed more intent on helping himself.

All these grumblings soon came to a head with the fracas over artificial milk.

Again, Liebig’s daughter Johanna struggled to produce enough milk to breastfeed. At the time, women in her position sometimes hired wet-nurses—working-class women who were already lactating and could feed other babies with their spare milk. In some European cities, almost half the infants had wet-nurses.

But the practice left people uneasy. Who would let another woman nurture their baby—and a poor woman at that? People are always quick to judge when it comes to raising children. To compound the problem, wet-nurses were often scarce and expensive, too.

To avoid wet-nurses, some families mixed up a crude baby formula of flour and cow milk. Unfortunately, most babies’ stomachs rejected this formula, so it never found much use.

That’s when Liebig stepped in. He used his organic chemistry knowledge to analyze breastmilk, then develop a superior formula: it was one part wheat flour mixed with ten parts powdered, skim cow milk. He also added potassium bicarbonate to make the mixture less acidic.

His big innovation involved adding malt. Malt is grain that has started to germinate. Germinating grains contain an enzyme called amylase. Amylase breaks the starches in flour down into simple sugars, which are easier for babies to digest. It was like baby fertilizer.

Liebig spoon-fed the first batches of artificial formula to his granddaughter Carolina. She reportedly thrived. And, never one to miss a business opportunity, Liebig began promoting the formula in 1865. He called it “soup for babies.”

Once again, he put the recipe in the public domain. But he also doled out free licenses for certain pharmacists to use his name and likeness while selling the formula. So while he earned no royalties, he did earn loads of goodwill and publicity. That in turn boosted sales for his other products, like the meat extract. Again, he was shrewd.

In a publicity coup, word leaked out that Liebig’s baby formula was helping feed Prince Albert Victor of England, the son of the future King Edward VII. Sales boomed.

But not everyone was thrilled. In fact, some people saw Liebig’s baby soup as downright dangerous.

Critics attacked Liebig’s baby formula for several reasons. First, it was hard to prepare. Some people bought ready made mixes from pharmacists, but many tried to make it at home instead.

Unfortunately, you had to get the proportions exactly right. The malting step was especially tricky. You had to heat the grains in water to a precise temperature; take the pot on and off the stove several times to prevent clumping; then cool the mix and filter it. Many people screwed up. Heck, many pharmacists screwed up, even after Liebig personally trained them. Not everyone was a worldclass chemist.

People also criticized the formula on moral grounds. Like it or not, childrearing and breastfeeding are fraught issues. People get worked up. Back then, mother’s milk was seen as a gift from God—nature’s perfect food. So who was Liebig to think he could improve on God’s handiwork? It seemed hubristic.

The most damning criticism, however, was also the simplest. That many babies struggled on the formula. They could not gain weight and suffered obvious stomach pain. This was troubling news.

In 1867, a doctor at a hospital in Paris finally tested the formula in an experiment. He found four newborns whose mothers could not breastfeed them. They ranged in weight from 5 to 9 pounds. Liebig himself prepared the first batches of formula.

But that did not prevent a disaster. The French doctor started feeding a set of twins. They were dead within two days. Two other babies developed green diarrhea—a sign of starvation. They died within days, too.

At that point, the doctor halted the experiment. When he announced his results to the French Academy of Medicine, a scandal erupted in the press. Imagine the headlines. Justus von Liebig, a noted humanitarian and the most famous chemist in the world, was killing babies.

German scientists rallied to his defense. They criticized the French doctor for not diluting the formula enough for newborns, who need weaker food. They also argued that the babies were near death when the experiment started and would have died no matter what. Liebig’s formula had nothing to do with it.

The great Liebig himself soon weighed in with a letter to the French academy. Far from his formula being poisonous, he said, “Thousands of infants of the Teutonic race … fed with [my] preparation are healthy and will continue to be.”

But that odd mention of Teutonic babies ended up backfiring. France still remembered Liebig’s nasty comments about mirrors and sickly Frenchwomen. At the time, France also felt threatened by the growing might of Germany, which was quickly becoming a military and economic powerhouse. In fact, France and Germany would go to war just a few years later.

Germany was overtaking France scientifically as well. And Liebig’s letter provided a chance to strike back. One academy member declared, “The German race may do well on [the formula], but the Latin race condemns and rejects it.” A debate over baby formula had now escalated into a fight for nationalistic supremacy.

Newspapers in other countries weighed in, too, as far afield as New Zealand. An English paper actually took the opportunity to bash both Liebig in Germany and the French doctor who’d tested the formula, accusing him of “scientific infanticide.”

So, yes, things got a bit heated. But when the emotions cooled down, most scientists judged that Liebig had lost the debate. A German scientist ran a thorough, controlled study in 1869 and found that Liebig’s formula was worse for infants than mother’s milk, wet-nurse milk, or straight cow milk. It was especially bad for children under two months.

We now know why. Infants struggle to digest starch. So even though Liebig added malt to help break the starchy flour down, that wasn’t enough.

More importantly, cow milk has too many proteins and minerals for human infants. A newborn’s digestive system therefore has to work overtime to break those excess nutrients down and eliminate them through urine. That’s hard on the kidneys.

Meanwhile, cow milk lacks other nutrients that humans need, like iron and vitamin C. That leaves babies anemic and malnourished. Liebig’s choice of powdered skim milk also meant his formula had no fat, which babies need lots of. Finally, cow’s milk can irritate the lining of a baby’s stomach and cause bleeding.

Overall, even if some babies did okay on it as a supplement, Liebig’s formula was probably doomed from the start.

And once his baby formula took a hit, people started looking more skeptically at his beef extract. They didn’t like what they found.

In an eerie echo of the baby experiment, a German scientist fed some dogs nothing but beef extract for a while. Every single one died.

It turned out that, chemically, the extracted goo had zero nutritional value. It tasted like beef. But in rendering the slurry and skimming things off the top, the manufacturers had removed all the fat and protein—all the calories. It could therefore not nourish people. The profit motive had indeed warped Liebig’s scientific judgment.

Liebig’s company quickly pivoted, and began marketing the extract as seasoning instead. Kinda like bouillon cubes. But between the dead babies and the dead dogs, Liebig took a real black eye.

But the crazy thing is, none of this permanently dented his reputation. People continued gobbling up the beef extract, buying 500 tons per year. The Allied army was still dishing out this German goo during World War II—when they were fighting Germany. After Liebig died in 1873, he had a university named after him. People were still awed by the illustrious name of Justus von Liebig.

In the end, given the limitations of chemical knowledge then, Liebig probably faced an impossible task in making good artificial milk. And the fraught politics of breastfeeding meant that people would have blasted him anyway, even if he’d succeeded.

But Liebig deserves credit for one thing—for realizing that science could help solve the widespread problem of malnutrition. His fertilizer work genuinely helped curb famines. And however clumsy the attempt, Liebig’s famous name gave legitimacy to the idea that chemistry could help mothers feed their hungry babies—eventually leading to the balanced, nutritious formulas of today.

Justus von Liebig certainly knew how to help himself. But his work helped save millions of lives as well.