In this episode of The Disappearing Spoon, Sam Kean talks about the strange origin story of the American Medical Association. The creation of this powerful medical society can be traced back to a duel between two doctors at Transylvania University in Kentucky.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

The two doctors flipped a coin. After it landed, one doctor went left, the other right. They marched off 10 paces. Then they turned, raised their pistols, and prepared to kill each other.

Normally, of course, doctors save lives. But in 1818, brawls between doctors were alarmingly common. Not all of them ended like this one, in a duel. But one doctor in Philadelphia during that era agonized over how his colleagues, quote, “lived in an almost constant state of warfare.”

The reason for this warfare was simple. Competition. The United States then turned out five times as many doctors per capita as some European countries, so there was fierce competition for patients. Doctors beat each other bloody all the time for stealing business.

But this duel in 1818 was especially noteworthy. That’s because it kicked off a series of events that led to the formation of the most powerful medical society in the United States.

That’s right. The American Medical Association itself traces back to this scuzzy skirmish and the backlash it provoked to find somehow, some way to prevent doctor-on-doctor murder.

This duel began in Transylvania. Not the homeland of Dracula, but Transylvania in east-central Kentucky. It’s a forested region bounded by the Ohio, Kentucky, and Cumberland Rivers.

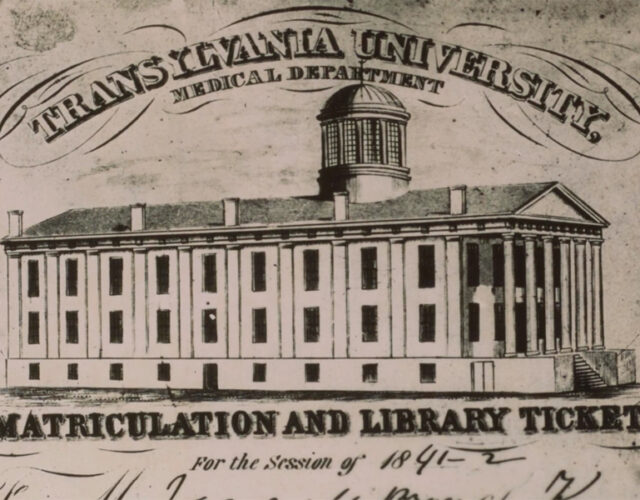

The Transylvania Seminary opened in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1785. A medical school followed in 1799, the first medical school in the American West. And I know what you’re thinking. Kentucky, the 1700s, attached to a seminary. The school had to be a backwater, right?

Well, think again. Transylvania University was better than most Ivy League schools—truly elite. George Washington and John Adams both donated money to fund it. It had one of the best libraries in the United States, and Thomas Jefferson himself recommended sending students there instead of Harvard. That’s because Transylvania U turned out good, salt-of-the-earth types, Jefferson said, not the, quote, “fanatics and Tories” that Harvard did.

Transylvania Medical School was elite as well, although it had just five faculty members. And unfortunately, two of them—Daniel Drake and Benjamin Dudley, both age 31—absolutely hated each other.

The two had first met in the early 1800s, as medical students in Philadelphia. Daniel Drake was an outsider to the big city, having been raised in a log cabin. He had curly hair and a big nose on a gaunt face.

He specialized in botany and pharmacy, and by all accounts he was an electric teacher. One witness recalled that, during his lectures, “words dropped hot and burning from his lips, as the lava falls from the burning crater.”

Drake got especially fiery about the necessity of boiling surgical instruments to clean them. He couldn’t have known about microbes then, but instinct told him that clean instruments were healthier. He was right, and this simple step no doubt saved thousands of lives.

Meanwhile, his colleague was Benjamin Dudley. Dudley had a snub nose and baggy eyes with sideburns. He also had an entrepreneurial streak. He once sailed a shipment of flour from New Orleans to Gibraltar, where he made a killing. At Transylvania Med, he taught anatomy.

Dudley and Drake’s falling out began over a third colleague, William Richardson. Richardson had soft eyes and a handsome if slightly chubby face. Richardson studied, quote, “diseases of women and children.” He’d also been a classmate of Dudley and Drake in Philadelphia, and that’s where the trouble started.

Medical school back then was not exactly rigorous. You paid $110, about $1700 today, and sat through the same six-month course of classes two times in a row. After that, you could start treating people—as well as brawling with fellow doctors over patients.

Except, Richardson apparently got impatient. He never finished the second six-month go-round of classes. Instead, he began courting wealthy patrons right away. He soon became the doctor for several respectable families. He then parlayed that prestige into a faculty job at Transylvania U.

Now, what happened next isn’t clear. But somehow, in the mid-1810s, Dudley the anatomist caught wind that Richardson had dropped out of medical school. And, given the uncollegiate atmosphere of medicine then, he tried to get Richardson fired.

Meanwhile, Drake the fiery pharmacist sympathized with Richardson and wanted to defend him. So Drake arranged for a medical school in New York to grant Richardson an honorary degree. Honestly, it sounded pretty shady. But it saved Richardson’s job on a technicality.

Unfortunately, Drake’s gambit angered Dudley. He felt double-crossed, and after several quarrels over the matter, the two former classmates became devoted enemies—grumbling at each other in the hallways for years. Then, a dispute in 1818 turned their dislike into open warfare.

It started with an Irishman in Lexington. This lad got stupid-drunk one day, and engaged in some fisticuffs. Someone then knocked him silly, <POW> and he smacked his head on a curb. Not long after, he died. City officials called on Dudley and Drake to perform an autopsy.

Drake declined. He was traveling that week, and didn’t have time. So Dudley the anatomist did the autopsy alone. He examined the Irishman’s swollen brain, and declared that this was what had killed him. Pretty straightforward. Or so he thought.

Drake soon came back from his travels. And although he hadn’t even been in the state at the time, he publically accused Dudley of botching the autopsy.

We don’t know why exactly Drake called Dudley out. But one historian ventured a guess. As an anatomist, Dudley needed dead bodies to dissect in his classes. Usually this involved buying bodies from grave-robbers, a dirty business.

So with the dead Irishman, perhaps Dudley saw an opportunity. It seems that he did examine the Irishman’s brain—but only the brain. He kept the rest of the body intact for his anatomy class. This prevented him from having to buy another body on the black market.

So his enemy Drake might simply have been pointing out, correctly, that you can’t determine how someone died by examining the brain alone. You have to look at the whole body. Therefore, in skipping the full autopsy and helping himself to the body, Dudley had neglected his duty. It was a serious charge.

And Dudley did not take the accusation lying down. He fired back in print. Drake then answered Dudley, and like a modern Twitter war, the two doctors began exchanging sharp words in pamphlets and newspaper articles. In them, Dudley accused Drake of plotting to defect to another medical school. Drake in turn called Dudley “an ignoramus, a bully, and a liar.” Probably a poltroon, too.

Obviously, Dudley could not stand for this. He challenged Drake to a duel.

In the early 1800s, duels were common in the South. At their peak, New Orleans had three to four duels every day. You had members of Congress shooting at each other, future governors, everyone. Even life-saving doctors joined in.

One especially wild duel took place in Jamaica in 1750. It involved sword fights, ambushes, insult poetry, and a mysterious blood disease. You can hear all about it in a bonus episode at Patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

But to stick to the Transylvania story, Dudley challenged Drake to a duel. Drake, however, thought the whole Southern honor thing was stupid. He refused to take part. And that’s when the story took a dramatic twist.

You see, when Drake said no, his colleague William Richardson stepped forward. Remember, Drake had once saved Richardson’s job by arranging for the dubious honorary medical degree. Now Richardson would return the favor and defend Drake’s honor by taking his place in the duel. Dudley said good enough—he wanted to shoot both bastards anyway.

The two agreed to a date in August 1818. Each man would have a second, and another doctor would be on hand to handle any injuries.

The duel took place a few miles north of Lexington, near the county line. Why there? Because duels were technically illegal. So if the sheriff of one county caught wind of it, Dudley and Richardson could just scoot twenty feet over into the other county. The sheriff lacked jurisdiction there, and the duel could proceed.

Now, it’s likely that neither doctor had much experience with guns. And back then, pistols were difficult to aim. But Dudley was determined to have the upper hand.

For his anatomy classes, Dudley relied upon a grave-robber named Christopher Columbus Graham. As a lowlife, Graham knew his way around a pistol. So he started training Dudley on how to shoot.

To practice, they would actually stand in Dudley’s house and shoot bullets across his widest room. Dudley soon got pretty good. Graham also knew some tricks. He tore all the shiny buttons off Dudley’s green overcoat, so Richardson had nothing to aim at.

On the fateful day, the two men met in a clearing in the woods. I imagine it as morning, with birds chirping and a thick blanket of humidity. Then the combatants flipped a coin, and marched ten paces to each side. Each man raised his pistol and…

Richardson missed by a mile. Dudley did not. He nailed Richardson right in the groin.

Richardson collapsed in agony. The bullet had severed an artery. The other doctor on hand rushed forward to save him. But the tourniquet he applied did no good. Richardson began bleeding to death right there in the forest.

When word of this reached town, the incident scandalized Lexington. Doctors—shooting each other? The next day dozens of citizens marched on City Hall to outlaw this barbaric practice.

Other doctors were outraged, too. In fact, the very next year, a Lexington doctor founded an organization to halt violence among physicians. He called it the Kappa Lambda Society.

In some ways, Kappa Lambda was simply a boys’ club, a frat. Membership was top secret. In fact, members acknowledged each other only through a secret code word. That word was primitive—which they awkwardly shoehorned into conversations. “Say, looks like primitive weather today.” Or maybe, “Lord, I am hungry—I could eat a primitive horse.”

But however dumb this sounds, Kappa Lambda worked. Doctors liked being in the secret club, and didn’t want to hurt fellow members. So they resolved disputes without shooting or clobbering each other. Kappa Lambda soon spread to New York and Philadelphia. It certainly didn’t end the fighting, but it helped.

The only problem was—the Freemasons. Let me explain.

In 1826, a man in northern New York state tried to publish a book exposing the Freemasons as dastardly villains. Except, he never got the chance. First, the printing shop mysteriously burned down. Then, four men grabbed the man one night and shoved him into a yellow carriage. Not long after, <SPLASH> a mutilated body was found in a nearby river.

The police never arrested any culprits, but it didn’t exactly take Sherlock Holmes for everyone to figure out the Masons were behind this. And for whatever reason, this local scandal exploded nationally. It sparked anti-Mason fury across the country, with suspected Masons suffering regular beatings.

Pretty soon, people began lashing out at other secret societies as well. You’ve heard of Phi Beta Kappa, the college honor society? Well, it started as a secret society at East Coast universities. But during the anti-Mason violence, its members swallowed hard. The fun of being in a secret club didn’t seem worth their lives. Shortly afterward, Phi Beta Kappa transformed into the harmless, open academic society of today.

The secret Kappa Lambda Society came under scrutiny, too. Every time a member mentioned some, uh, primitive clock tower or whatever, the eyes of passersby went wide with fear. In Philadelphia, medical journals began foaming at the mouth about certain hospitals being overrun with Kappa Lambdas. Accusations flew left and right.

People also named names in New York, and lists of members were printed and posted. It was just like people outing communists in the 1950s. Doctors across the country quickly began dropping out of Kappa Lambda. It was not worth their careers.

Still, these doctors had seen the value of the club. It tamped down on duels and other violence. So some physicians began calling meetings in the mid-1840s to discuss starting another club—an open one. Finally, in 1847, they built on the ruins of Kappa Lambda to found the American Medical Association.

Now, they founded the AMA for several reasons. One was regulating quack treatments, which were flourishing then. But beyond those medical concerns, the association’s constitution explicitly addressed the need to quote, “foster… friendly intercourse between [doctors].”

Today the AMA is a powerhouse, one of the most respected institutions in the world. Ultimately, though, we can trace its origins back to that bloody, lowdown duel from 1818.

So then what happened to the people involved in that duel? Well, Drake and Dudley, the original antagonists, never reconciled. But Dudley and Richardson? That’s another story.

Remember, Dudley plugged Richardson in the groin, severing an artery. Blood was spurting everywhere, and the extra doctor on hand could not stop the bleeding, even with a tourniquet.

But seeing his colleague soaked in blood, writhing in agony somehow thawed Dudley’s heart. After all, Richardson had been brave to step in and accept the challenge for another person. So Dudley stepped forward, leaned down, and asked if he could help.

Richardson nodded weakly. Dudley then used his expertise in anatomy to apply some pressure with his thumb at just the right spot. A minute later, the geyser of blood slowed, and then stopped. This bought just enough time, and the other doctor tied the artery off. Dudley had saved Richardson’s life.

Sadly, this wasn’t enough to save Transylvania Medical School. Although it once rivaled Harvard, the petty squabbling among the faculty continued for years. Drake and other doctors soon defected for rival institutions. Then the school’s seminary began interfering with scientific matters. This disharmony eventually destroyed a great medical school.

But with Dudley and Richardson at least, all was forgiven. Like soldiers bonding in combat, they became dear friends after the duel. And while they couldn’t save their school, from the ashes of their bloody feud in Transylvania arose the American Medical Association—as well as a new, more collegial era in the never-ending battle to save lives.