Every aspiring chemist has heard of Boyle’s law—the equation that relates the pressure of a gas to its volume. But even if you know about Robert Boyle himself, it’s not likely you’ve heard of his sister, even though she probably talked him through many of his ideas.

Katherine Jones, Lady Ranelagh (1615–1691), had a lifelong influence on her famous younger brother, natural philosopher Robert Boyle. In her lifetime, she was recognized by many for her scientific knowledge, but her story was almost lost to time.

This episode is a collaboration with Poncie Rutsch, the creator and host of Babes of Science. Poncie interviewed the Institute’s own Michelle DiMeo, a historian who’s writing a book about Lady Ranelagh. Babes of Science is a podcast that tries to answer two questions: Who are the women who changed the trajectory of science? And why has it taken us so long to recognize their work?

Credits

Hosts: Michal Meyer and Bob Kenworthy

Reporter and producer: Poncie Rutsch

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Our theme music was composed by Zach Young

Additional music courtesy of the Free Music Archive:

- Day Into Night by Rho

- Daydream Shelshock by Wolf Asylum

- Am I The Devil by YEYEY

- History Explains Itself by The Losers

- Like Swimming by Broke For Free

- Insatiable Toad by Blue Dot Sessions

- One And by Broke For Free

- Modulation of the Spirit by Little Glass Men

- Melt by Broke For Free

- Eleanor by The Losers

- I Am A Man Who Will Fight For Your Honor by Chris Zabriskie

- Tidal Wave by YEYEY

Transcript

The Almost Forgotten Story of Katherine Jones, Lady Ranelagh

The Woman Beside the Father of Chemistry

Michal: Hello and welcome to Distillations, the science, culture, and history podcast. I’m Michal Meyer, a historian of science and editor in chief of Distillations magazine.

Bob: And I’m Bob Kenworthy, CHF’s in-house chemist.

Michal: Before we get started, we have two pieces of news. As you probably know, Distillations is produced by the Chemical Heritage Foundation, a non-profit organization based in Philadelphia.

Bob: And CHF has been going through some big changes recently. In 2015 we merged with the Life Sciences Foundation, out in the San Francisco bay area.

Michal: And on February 1st we’re leaving our old name behind and becoming the Science History Institute. Science and history are at the core of what we do—and our new name makes that crystal clear.

Bob: Distillations will keep coming out each month and you don’t need to make any changes to your podcast feeds. You’ll still be able to find us online at distillations-dot-org.

Michal: You can find out more about this transition at C-H-E-M-heritage-dot-org-slash-news. Bob: The other news is that next month Michal and I are handing our microphones over to

Distillations’s new hosts: Lisa Berry Drago and Alexis Pedrick.

Michal: You might remember Lisa and Alexis from November’s Butter vs. Margarine show. They did such a good job we decided they should keep doing it.

Bob: Lisa is CHF’s Public History Fellow and an art historian. She’s interested in the places where art and science interact, and in the untold histories of science: stories about gender, race, class, and power. In her spare time she writes fiction, makes comics, crafts, and grows too many tomatoes in her little south Philly garden.

Michal: As the leader of CHF’s public programs Alexis hosts science lectures in bars, is an active member of Philly’s geek community and is known for her popular history talks at Nerd Nite. She has a standing Dungeons and Dragons night with her friends and when she has some spare time she leads macabre history tours in cemeteries.

Bob: We’re going to miss this gig, but we’ll still be working behind the scenes, making sure they get the science right.

Michal: And the history, of course. Now let’s get back to this episode!

Bob: Every aspiring chemist has heard of Boyle’s law—the equation that relates the pressure of a gas to its volume. But even if you know about Robert Boyle himself, it’s not likely you’ve

heard of his sister, even though she probably talked him through many of his ideas, either in person or through letters.

Michal: This episode is a collaboration with Poncie Rutsch, the creator and host of Babes of Science.

Michal: Babes of Science is a podcast that tries to answer two questions: Who are the women who changed the trajectory of science? And why has it taken us so long to recognize their work?

Poncie Rutsch: Lady Ranelagh sits at her table, penning a note to her brother, Robert Boyle. You might have heard of Robert Boyle…he’s a chemist who’s famous for his work relating a gas’s pressure to its volume. So famous that his name eventually ends up on an equation that every chemistry student knows: Boyle’s Law. Some people even refer to Robert Boyle as the “father of chemistry.”

Poncie: Boyle and his peers are extremely curious about the world around them, but not so sure how to answer their big questions. Before Boyle’s 17th century lifetime, thinkers and philosophers had deduced truth and science from ancient philosophy, because they didn’t believe they could trust their perception of the world.

Poncie: But Boyle argues that it’s more accurate to draw conclusions from people’s observations about the world around them. Or from setting up an experiment to test different ideas about some natural phenomenon—even if the experiment was unsuccessful, Boyle asserts that it’s useful!

Which…forgive me for pointing this out, but it sounds an awful lot like how science works today: experimentation and observation.

Poncie: Robert Boyle isn’t working alone: his published work refers to partners and

collaborators. Or he’d publish their response to his ideas. But Robert’s most frequent and influential collaborator—his intellectual partner!—is his sister, Katherine, even though she never appears in his work by name.

****

Poncie: Katherine Boyle is born March 22, 1615 in Ireland, one of the Earl of Cork’s fifteen children. And because her father is extremely wealthy, Katherine and her siblings have access to mentors and tutors and education. But of course that access looks different depending on if you’re a son or a daughter. Sons attend boarding school, and work with mentors and tutors.

Poncie: Robert Boyle, who’s Katherine’s younger brother by 12 years, heads to Eton College (which to this day is a really classy boys’ boarding school).

Poncie: And Katherine might join in on some of her brothers’ tutoring sessions that took place at the Boyle family home. But typically, daughters end up in marriage agreements. Katherine, for example, is contracted to marry Sapcott Beaumont. Her father promises the Beaumonts four thousand pounds, 3500 paid upfront in 1624—which is at least half a million in today’s dollars.

Poncie: So Katherine goes to live with the Beaumont family in England when she’s just nine years old. And when that agreement falls apart—Sapcott Beaumont’s father dies and his family demands more money, so EarlCork/PapaBoyle says nope and brings Katherine home—there’s a new marriage contract just a few years later: Katherine marries Arthur Jones in 1630 at the age of fifteen.

****

Poncie: After their wedding, Katherine and her husband travel together and Katherine seems like she’s trying to make it work. The couple has four kids. But in Katherine’s letters to family, she refers to her husband’s “sting” and says that he is “guilty of play.” Which is 1600s nice for

“cheating bastard.”

Poncie: And as they travel, Katherine builds and maintains her social network, keeping everyone she knows and loves abreast of her life and her relationships. When their travels come to an end, she and her family move to Athlone Castle—a really old castle in central Ireland. Which is where Katherine gets stuck during the Irish rebellion of 1641. She tries to send letters to her

family, but it’s a lot to ask of the people carrying those messages—one messenger gets stoned to death when she’s trying to deliver a note.

Poncie: Katherine finally negotiates her way out of the castle toward the end of 1642. One of the Irish rebels smuggles her out with her children, and they make their way to London. It’s right

about now that Katherine’s husband Arthur inherits the title Viscount of Ranelagh, so people start calling Katherine, Lady Ranelagh. Just in time for them to separate.

Poncie: Now—divorce isn’t exactly a regular course of action for your typical 1640s lady. But because Katherine’s husband is busy fighting in Ireland, he’s a little bit tied up when she asks for that separation. And when she arrives in London, she steps right into the middle of the English Civil War. Which is pretty miserable but it just so happens that the court system isn’t functioning during the war—from 1644 to 1660.

Poncie: Many of Katherine’s friends and her similarly wealthy and influential brothers begin writing letters and appealing privately to parliament—because without a court, it becomes parliament’s responsibility to settle legal disputes. Even Oliver Cromwell takes an interest in

Katherine’s case. So even though what she’s doing is unusual, no one seems to judge her for the separation or for taking custody of her and her husband’s children. She’s got tons of support!

Which…is a pretty good indicator of her privilege and influence. Katherine even gets to keep her title; since she and Arthur never formally divorce, she remains Lady Ranelagh.

Poncie: So Katherine and her children settle in London. And her new house is never empty really. She opens her home to her family members displaced by war and rebellion in England and Ireland. Two of her sisters move in over the next few years.

Poncie: And since Katherine is no longer under house arrest…err…Athlone castle arrest, she and her brother, Robert Boyle, reconnect. That is, after Robert’s done travelling the continent (aka the rest of Europe) because that’s what the sons of the Earl of Cork do (for their education, of

course). Robert stops in for a visit in 1644, and then he moves to Stalbridge—to one of the

Boyles’ family estates in southwest England—and using her connections, Katherine helps him find and purchase lab equipment so he can maintain his own chemistry lab.

Poncie: And thus, the Boyle siblings begin their independent experiments, and they spend the next twenty-four years discussing their work: when they can’t visit one another, they report by mail from wherever they are.

****

Poncie: One of Katherine’s and Robert’s recurring projects is their work with medical remedies. During the 1600s, most people turned to their communities for medical care, only seeking a doctor when a homemade remedy failed.

Poncie: And these remedies might come from a family book filled with recipes that a mother or a grandmother had collected and written by hand. Or you could buy a generic collection from a bookstore…which might be filled with recipes that no one had ever actually tested. Or you might have just heard of a remedy from someone in your town. Most of the ingredients are things that you’d keep in your kitchen or home garden—herbs, spices, pantry items. If it’s a more obscure ingredient, or the home garden is small, you head to the local apothecary to stock up.

Poncie: And there are remedies for everything: fevers, coughs, toothaches. Some you swallow, others you might be rub onto the skin. And if one doesn’t work, there are dozens of others to try. Some apothecaries even make their own remedies that you can buy, pre-mixed.

Poncie: Katherine and Robert maintain their own recipe books, with remedies that treat a range of maladies. And within their communities, people seek both Katherine and Robert out for their recipes and strategies.

Poncie: One malady that brings people to their doors is Rickets, which is kind of like osteoporosis, but for kids. If a person doesn’t get enough vitamin D or enough calcium while their bones are still growing, the bones fracture easily, or they might bend instead of growing straight. That’s Rickets.

Poncie: Now, neither Katherine or Robert (or anyone else for that matter) know what causes Rickets. But they can recognize the symptoms—the bow leggedness or widened wrists. And they have a remedy that seems pretty effective.

Poncie: Katherine and Robert call their recipe the Flowers of Colcothar. Colcothar referred to a concoction made from copper, and to make the remedy, Katherine and Robert mix the colcothar with an ammonium salt called sal ammoniac. And even in the mid-17th century, people know that too much copper is dangerous. So…these are not ingredients that the apothecary would just fork over to the common housewife. But the apothecaries trust Katherine and Robert, so they supply them.

Poncie: And if the apothecaries’ trust isn’t enough credibility, Katherine and Robert probably earn their reputation in part through word of mouth. Once their remedies ease one person’s ailment, other people want to try it out. Plus, visiting a doctor usually meant he would try bloodletting or he’d make you sweat or vomit—all attempts to purge the illness from your body.

Poncie: Robert and Katherine tease the bloodletting and vomiting practices in their letters to each other. They dole out a lot of snarky commentary about traditional medicine. And they discuss why their remedies are more effective.

Poncie: Because…Robert and Katherine are keeping track as they share their remedies with patients. They note when the remedy works or fails with a system of notes and checkmarks. When Katherine administers the remedies, she adjusts the dosage for different people or types of bodies—larger dose for a bigger person, for example. She also follows up with patients to see if they’re still experiencing symptoms—if they are, she adjusts her recommendations until they’ve been cured.

Poncie: Robert and Katherine say that it’s the repeated trials that make their practice with remedies more effective than traditional medicine. Robert once claims that they’ve cured hundreds with one of their remedies.

Poncie: It’s possible he’s exaggerating…but the point is, they’re noting what works and what doesn’t. And then they’re altering their approach and repeating the process. Which makes Katherine and Robert Boyle two early chemists practicing what we might today call the scientific method.

****

Poncie: Robert would go on to publish some of his and Katherine’s work with remedies—and he published some of their other collaborations too—Katherine would suggest an idea, or Robert would ask her to edit an essay he’d been mulling over.

Poncie: But Katherine wouldn’t publish that work alone. She would never! The name Lady Ranelagh wouldn’t appear in Robert’s work. And mostly, this was for modesty’s sake.

Poncie: For most of the 1600s, women wouldn’t publish their own work—those who did were the exception, not the rule. A woman of Katherine’s status didn’t want to give anyone the impression that she needed to write to make money. She wanted to project that her estate and her inheritance could support her until her death. And if she had extra money or time, the socially acceptable thing for Katherine to do would be to help others through charity work. Sharing her remedies was a way of caring for her community, but writing or experimenting for recognition might label Katherine as selfish.. And her reputation was in question too—a woman who wrote was a woman with loose lips, and a woman with loose lips might be loose in other ways too.

Poncie: Occasionally, women’s work would get published after they died. That’s when they could take credit, because their modesty was no longer at stake.

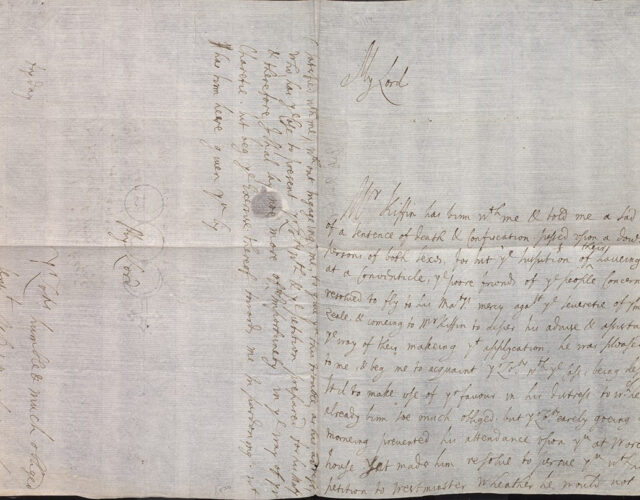

Poncie: Instead, Katherine’s work circulates as manuscripts—she would write out a report and someone might copy it by hand, so there would be just a handful of copies in existence. Today we would think of a manuscript as the first step in the publishing process, but Katherine’s goal was simply to share her notes and findings with trusted friends or with the Hartlib circle, which was kind of a predecessor to the Royal Society—so, a network of thinkers scattered across Poncie: Europe who corresponded to discuss their ideas and their work and their writing.

Katherine is writing to members of the Hartlib circle about all sorts of things—not just her work with remedies but also social reform and politics and education.

Poncie: It’s impossible to know if Katherine actually wanted to publish her works and just felt that she couldn’t do so. But just to take a quick detour: a friend of hers, Lady Marsham expressed her frustration in a letter to the philosopher John Locke in 1685:

Poncie: “How ever perhaps you may see me in Print in a little While, and then need not be Beholden to me, it being growne much the Fasion of late for our sex, Though I confess it has not much of my Approbation because (Principally) the Mode is for one to Dye First; and at this time if I might Have my owne Choice I Have no Great Inclination That Way … But I am not without some Apprehension that I am to do so in a little Time As within Half a Yeare or There abouts”

Poncie: The language is tough on my ears too but basically Lady Marsham is saying: You’ll only see me in print if I die first. And though I’m not super stoked to die, I am pregnant so it could happen. Bleak, Lady Marsham!

Poncie: But back to Lady Ranelagh. It’s possible that sharing manuscripts and writing letters accomplishes exactly what Katherine wants it to—she shares her work comfortably, because she knows it won’t circulate beyond her trusted peers: people who know that Katherine is a virtuous and religious woman, and won’t doubt her intentions.

Poncie: And there are nods to Katherine in Robert’s work, even if her name isn’t there. When Robert writes to a mutual friend, he refers to “a kinswoman close to you and I.” Or he dedicates his work to a “mistress of wit and eloquence.” Or he talks about a mysterious woman named Saphronia. Which HAS to be Katherine.

Poncie: Everyone close to Robert Boyle knows that Katherine is his intellectual companion. His editor. His most trusted collaborator. So the people close to them would understand Robert’s reference and know he’s crediting Katherine for her input. And if they don’t know Robert or Katherine well, then the mystery collaborator remains a mystery, and Katherine’s reputation stays immaculate.

Poncie: In 1668 Robert moves into Katherine’s home in London—she outfits another chemistry lab for him, this time in her house. And the two of them live there until their deaths, during the same week in 1691.

****

Michelle DiMeo: I just wonder how many more women were writing about these things in manuscripts or reading the drafts that men were publishing or talking with people, holding salons in their houses.

Poncie: This is Michelle Di Meo.

Michelle: My name is Michelle Di Meo. I am currently the director of Digital Library Initiatives here at The Chemical Heritage Foundation. I am also a historian of early modern science and medicine.

Poncie: Michelle’s been researching Lady Ranelagh for more than a decade, beginning when she was in graduate school.

Michelle: When I started writing my dissertation I felt like by the end of it I knew her so well, but I was so scared that I was getting it wrong and I had this dream where I saw her, out of all places, at a deli and she walked up to me, and shook her head and said you’ve got it all wrong.

Poncie: And Michelle DiMeo’s hyper focus on Katherine, whom she refers to as Lady Ranelagh, made me think differently about how I choose Babes of Science. Previously, if I couldn’t point to a specific contribution that wouldn’t exist without the woman in question, I didn’t continue with my research. Because there are so many women who contributed very specific things to science, it seemed silly to focus on anyone whose legacy was, well, debatable.

Poncie: But that kind of criteria cuts out a lot of people. And not because of the importance of the person’s work…but because of how it’s documented. Take, for example, the Boyle family paper trail:

Michelle: When Robert Boyle dies he has a very detailed will and testament, he leaves literary executors to his will. He has color-coded boxes and ribbons and he says where all these things can be found in his house. He’s very careful about creating his legacy as he’s dying. Whereas LR, there’s no will. The only letters we know about survive mostly in the archives of the men that she knew.//

Poncie: Let’s pause for a second and consider the effort of compiling an archive of letters. When you send a letter, it ends up in someone else’s mailbox, right? Lady Ranelagh sends hundreds of letters. No…probably thousands of letters! A researcher named Evan Bourke analyzed her correspondences and placed her in the top 20 of the more than 700 people associated with the Hartlib Circle. So in order to collect all the letters Lady Ranelagh wrote, you would need to know everyone she wrote to, and you would hope that they each maintained an organized letter archive, and perhaps most importantly that those letters survived over the last 300 years. So yeah, it’s hard to track Lady Ranelagh down.

Michelle: And it becomes a problem almost immediately after she dies.

Poncie: Because the most obvious recipient of Lady Ranelagh’s letters is her brother, Robert Boyle. And when Katherine and Robert live apart, the letters she sends him demonstrate how involved, how essential her participation is to his thought process. Early in his chemistry explorations, Robert writes to Katherine when something goes awry, to express his frustration. They exchange ideas about experiments or applying their remedies, and if they can’t find the ingredients they need—like lemons, or mistletoe, they ask if the other has any to spare. And when Robert starts writing more formally, Katherine edits it, and sends it back to him.

Michelle: when Boyle moves in with her, we have very little evidence because they’re not writing letters anymore.

Poncie: Luckily, she and Robert interact with plenty of other thinkers too…who don’t live with them.

Michelle: We do know that she’s involved because we have diary entries. Like Robert Hooke and John Evelyn who say that they come over and when they talk with Robert Boyle they talk with Lady Ranelagh. So we know that it happened, it’s just we just have far less evidence at that point of what she’s actually doing. And if she’s reading drafts or attending the experiments, we just don’t know because he’s not writing it down anywhere.

Poncie: But seriously, she couldn’t have kept a diary? Possibly on acid-proof paper and placed in a hermetically sealed box?

Poncie: Ok…Michelle says that many women actually did keep diaries. But the documents she’s seen reflect the writer’s religion and spirituality. Not her science experiments.

Poncie: So because there’s this gap between what actually happened and what’s documented, plenty of other women share the same issue as Lady Ranelagh, Michelle says, like Anne Conway or Dorothy Moore. What do they all have in common? They lived during the 1600s when people would get super judgy about women who published their work.

Michelle: I’m sure there’s many more. and I think part of the reason we don’t know

about these women is because they’ve been erased from the historical record. And it’s really sad!

Poncie: So once we move back in time, into the 1800s and earlier, we have to account for this gap in the evidence. And Michelle says that historians of science are taking it one step further.

Michelle: We try to get away, increasingly from this kind of genius narrative. That

there’s just one person who created something and changed the field. Increasingly what we’re trying to do is think about these communities of knowledge and the cultural moments and how advances are created in particular moments and why./

Poncie: Even when we can describe in detail the contributions of one particular person, the network surrounding that individual of course influences their contribution. Irene Joliot Curie’s

correspondence with Lise Meitner pushed Irene and her husband to keep their research a secret so it wouldn’t fall into the wrong hands during WWII. And of course: there’s no way Watson or Crick could have come anywhere close to defining the structure of DNA if Rosalind Franklin hadn’t shared her images with them. And now everyone seems to recognize that Rosalind Franklin is a big deal!

Michelle: These people who are supposedly influencing the field are drawing on the work of a lot of these kind of unknown people that we don’t know about and I think that they are a very important contribution as well.

Poncie: I’m with Michelle. It’s time to look past the first authors and the namesakes and start seeking out the partners and collaborators.

Poncie: This episode of Babes of Science was produced by me, Poncie Rutsch, in collaboration with Distillations Podcast. Babes of Science is a podcast that seeks to answer two questions: Who are the women who changed the trajectory of science? And why has it taken us so long to recognize their work? You can hear more at babesofscienceDOTcom, or by searching for Babes of Science in your podcast app.

Poncie: Special thanks to Michelle DiMeo, for her expertise, enthusiasm, and patience, and to Rigoberto Hernandez and Mariel Carr, for their guidance and editorial savvy. And thanks to you, for listening!

Michal: Distillations is more than a podcast. We’re also a multimedia magazine. Bob: You can find our videos, our blog, and our print stories at Distillations.org. Michal: Signing off for the last time: for Distillations, I’m Michal Meyer.

Bob: And I’m Bob Kenworthy.

Bob and Michal: Thanks for listening.