Everyone knows that observation is a key part of the scientific method, but what does that mean for scientists who can’t see? Judith Summers-Gates is a successful, visually impaired chemist who uses a telescope to read street signs. If the thought of a blind scientist gives you pause, you’re not alone. But stop and ask yourself why. What assumptions do we make about how knowledge is produced? And who gets to produce it? And who gets to participate in science?

In this episode, we go deep into the history of how vision came to dominate scientific observation and how blind scientists challenge our assumptions. This is the first of two episodes about science and disability and was produced in collaboration with the Science and Disability oral history project at the Science History Institute.

Credits

Hosts: Alexis Pedrick and Elisabeth Berry Drago

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: James Morrison

Music by Blue Dot Sessions: “Nesting,” “Our Only Lark,” “Building the Sled,” “Slimheart,” “Low Light Switch,” “Filing Away,” and “Watercool Quiet.”

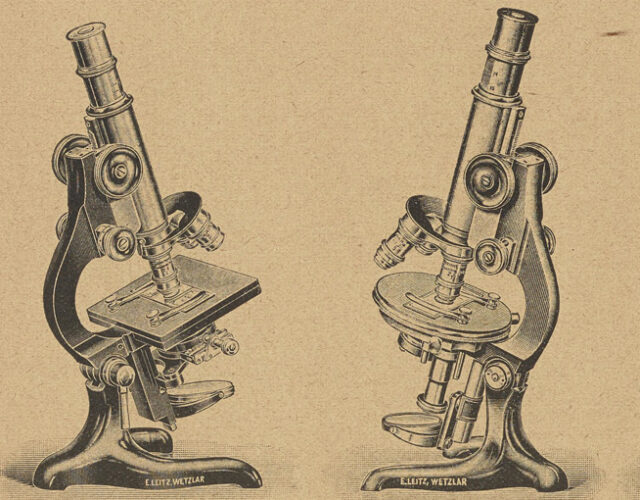

Image credit: Science History Institute Digital Collections

Resource List

Lemonick, Sam. “Artificial intelligence tools could benefit chemists with disabilities. So why aren’t they?” C&EN, March 18, 2019.

Martucci, Jessica. “History Lab: Through the Lens of Disability.” Science History Institute, June 22, 2019.

Martucci, Jessica. “Through the Lens of Disability.” Distillations, November 8, 2018.

Martucci, Jessica. “Science and Disability.” Distillations, August 18, 2017.

Slaton, Amy. “Body? What Body? Considering Ability and Disability in STEM Disciplines.” 120th ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, January 23, 2013.

Summers-Gates, Judith. Oral history conducted on 20 January and 6 February 2017 by Jessica Martucci and Lee Sullivan Berry, Science and Disability project, Science History Institute.

Transcript

Lisa Berry Drago: Prologue. The bird badge.

Alexis Pedrick: Judith Summers-Gates-Gates was born on April 1st, 1958. She was two months premature which led to some complications. As a child, she constantly got nose and joint bleeds and she had to get a lot of blood transfusions. Another complication was with her eyes. There was too much oxygen in the incubator where she spent the first two months of her life and this left her nearly blind.

Judith Summers-Gates: Back in those days, preemies that small didn’t always survive and in a lot of cases they did not. Or they had multiple, multiple more disabilities and would succumb due to the combination of things. Of the 10 kids who were preemies in the nursery at the time I was there, I was the only one that left. I went home with my parents. Everybody else passed on. So I was being stubborn even then [laughs].

Alexis Pedrick: Judith isn’t completely blind. She has what’s called low vision. She can only see things that are right in front of her and even that can be difficult. So, it might surprise you that Judith is a chemist. How does one become a chemist without being able to see? Judith calls it stubbornness. We’ll call it perseverance combined with imagination.

Judith Summers-Gates: The more you told me I couldn’t do something was more, more likelihood that I was going to be doing something or trying to be doing something that you weren’t going to be happy about my doing. So, yes. My poor mother had to keep a gentle leash on me as best she could to try and keep me from worse harm [laughs].

Alexis Pedrick: She did things other people told her she couldn’t. Like joining the girl scouts.

Judith Summers-Gates: Back then, I was, I was a terror in the girl scouts too. I have to tell you. Oh, because again, we would go on activities and they would say to me, “Well you kind of wait over here because we don’t want you to be involved in whatever this rough and tumble thing is.”

Alexis Pedrick: One year, Judith’s troop was competing for their bird watching badges. Each scout got a list of birds that they were supposed to find and check off a list. Judith knew this would be one of the things she’d be asked to sit out.

Judith Summers-Gates: What do I do about this? And we knew about this in advance of going to the camp so I had a chance to plan. And my mom had packed my duffel bag all up nice with all the close and you have the list of all the stuff you’re supposed to bring with you. I go upstairs in my bedroom and I unpack the duffel bag, take all the clothes out, most of the clothes, most of the gear and I threw in a 10 pound bag of birdseed.

Alexis Pedrick: Sure enough, when it was time to go bird watching, the troop leaders told Judith she obviously couldn’t go with them. They set up a craft table to keep her busy.

Judith Summers-Gates: So, you can do this while we’re doing the bird watching. Well, I wanted the bird badge. So, I mean I’m not going to sit here. That’s why I brought the birdseed. So, I dragged the birdseed out of my, my duffel bag and I went to the nearest clearing and I looked around and I was like, “This looks like a good spot.” And I threw the birdseed all over the clearing [laughs] and then I sat down with my binoculars and my notebook with my list of birds. And as they’re all, birds are coming from like 20 miles around. I mean, there’s like bird smorgasbord here. Every, I mean everything up to a pterodactyl was showing up here because it wanted this food. I mean, this, this was like open season. They’re all, you know, I mean literally there were hundreds of birds all sprawled out in this space gorging themselves on seeds. And I’m just sitting there check that one off and I was, as I’m finishing up, I hear the troop. It’s, okay, l- look, it’s about time for them to be coming back. I hear them tromping back through the, through the bush and they’re all and complaining. We didn’t see any damn birds. We don’t know what’s going on. There’s no birds around here. And then they hear the birds.They’re like, “What’s going on? Where’s, there’s birds. Where-” so, they all come barreling over to where we had put the cl- I was in the clearing and the leader’s just standing there and she’s, her mouth’s open. And she said, “I think we know why there weren’t any birds out there for us to watch. Because you got them all to come over here.” It’s like, “Well, it worked, didn’t it?”And here’s my list. It’s checked off.

Alexis Pedrick: The troop wanted to know how she did it and they started asking questions.

Judith Summers-Gates: Where did you get the birdseed? I brought it with me. You brought it with you. You knew you were going to do this. I said, “Well, you told me I couldn’t go with you. So how else am I going to find them? If I can’t go to them they have to come to me right? That’s, makes sense doesn’t it? You know? And she’s just shaking her head like, “Oh God. I can’t wait until this camping trip’s over.” But this, this was kind of like our, our, a symbolism for our whole entire girl scout experience. You know, because they’d be doing something one way and I’d say, “But wait a minute, I can do it another way.” There we go. [laughs]

Alexis Pedrick: Judith got her bird badge and she used that same ingenuity and persistence throughout her life to do a lot of things people told her she’d never be able to do. She went on to become a successful chemist with a long career in the government. She worked for the USDA, the Department of Defense and the FDA. I’m Alexis Pedrick.

Lisa Berry Drago: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago. And this is Distillations.

Alexis Pedrick: That interview with Judith Summers-Gates-Gates was done by Jessica Martucci, our former colleague at the Science History Institute. Jessica ran the Science and Disability Project in effort to document the lives and contributions of people with disabilities to STEM.

Lisa Berry Drago: This is the first of two episodes we’re bringing you about scientists with disabilities. This one is about scientists who, like Judith, are blind or have low vision. If the thought of an almost blind chemist gives you pause, you’re not alone. But stop and ask yourself why. What assumptions do we make about how knowledge is produced and about who gets to produce it? What does it say about who gets to participate in science and who gets to participate in society more broadly?

Alexis Pedrick: Back in the girl scouts, Judith got that bird badge, but only because she fought for it. She demanded to join the girl scouts against her mother’s wishes and she went ahead and identified those birds when she was supposed to be doing crafts and this persistence is basically how she made it through high school and college. How she landed her first job and her second and her third jobs. But this is not a story about just celebrating one blind scientist overcoming adversity. The point of the story is that it shouldn’t be this way. It shouldn’t have been so hard for Judith. Opening our minds to new and different ways of doing science from the get-go would mean more people like Judith could become scientists. Shutting people like Judith out of science isn’t just unkind. I mean, it’s definitely unkind, but it’s also dumb. Because people like Judith contribute important knowledge and ideas that we can all use.

Lisa Berry Drago: Chapter one. How did vision become king anyway?

Alexis Pedrick: I like imagining the looks on everyone’s faces when Judith identified all those birds in her unique way. I picture a lot of raised eyebrows and gasps and it was all because she seemed like she skipped that key step in the scientific method: Observation. Because observation equals looking with your eyes, right? Wrong. Here’s Jessica Martucci.

Jessica Martucci: Talking with Judith and, and revisiting her stories again and again, it does make you start to think why, why do we rely so heavily on vision when we have all of these other senses and all of these other ways of collecting information about the world?

Alexis Pedrick: In the ancient Greek and Roman world, and even up through the early Middle Ages, science didn’t rely on observation or sight. It was mostly done through deductive reasoning. Scientific evidence gathered through the senses was actually suspect. It was highly subjective and sensory impressions were fleeting. It was much better to pair observation with logic. Now, one kind of deductive reasoning was a logical argument called syllogism. Syllogism takes two known truths. One general and one specific and deducts a conclusion from them. Here’s an example. The general truth is that human beings have a circulatory system. The specific truth is that I am a human being. The conclusion is I have a circulatory system. You could use this syllogism for things like classifying types of animals or natural phenomena. All mammals are warm blooded. Cats are warm blood. Therefore, cats are mammals. In odd cases like, let’s say you’re trying to categorize a platypus, you could engage in debates that match syllogism against syllogism, arguing down the idea using deductive reasoning until you arrived at something that appeared to be the truth. Later, medieval thinkers introduced more first-hand experimentation and observation into their work, but logic and reasoning were still crucial to their process. So, to sum it up, you could say that argument, not sight was the king of this early scientific method. When Jessica talked to Judith Summers-Gates-Gates, she started wondering where our assumptions about vision and science even came from. Because even though they might seem innate, they had to start somewhere. And she traced it back to the origins of modern science. In the 17th Century, the scientific method is developing and people are having deep philosophical arguments about things like how do you create truth and how do you create objective knowledge about the world?

Jessica Martucci: And, you know, if you look to the scientific societies that are forming in that period, especially the Royal Society of London, there’s really intense debates going on about how do you, how do you take knowledge that someone has said that they’ve created and apply that more universally. So, you know, basically just because somebody said that they got this sort of result in a lab somewhere, how do we know that that is true in all cases? How do we know that we can trust that?

Alexis Pedrick: How can we trust that? Trust was a big thing. Just because someone says that they saw something doesn’t mean it’s true. Who even is this person? But then something big happened in 1655. The Royal Society published a book that tipped the scales and made vision king. It was called Micrographia by Robert Hook and it made waves for its incredibly detailed illustrations of insects and plants. Its most famous illustration to this day is a very detailed drawing of a flea. Before the book, most people had no idea what a flea actually looked like. To the human eye, they look like little dots. But this book made the microscopic visible and it was all thanks to a new invention: the microscope.

Jessica Martucci: When people think about science today, and especially life sciences, you think about microscopes. And everybody who goes through, you know, middle school, high school science classes, you’re going to encounter a microscope. They’re sort of this gateway tool into the sciences. But in the 17th century, microscopes were not seen as necessarily trustworthy. They required first of all, a lot of technical knowledge and skill that had to be built up and, and you had to, your eye had to really be trained and disciplined in order to recognize what it was seeing. And so those, there were a lot of arguments. You know, is, A, should we be trusting visual information and B, should we be trusting visual information that’s coming through this mechanical lens that can have imperfections or that require so much interpretation, and things like that. So, when Hook’s Micrographia came out, it sparked, it sort of fed into these debates that were ongoing about how do we, how do we know what we know? How do we trust what we’re seeing? Um, and things like that. If you look back at the, at this period, the debates that are happening are really about can we trust sensory information as, you know, a way, a way to see the true world or is the only way to arrive at true knowledge through kind of a philosophical reasoning? And observation, experiment, vision won out and that’s sort of what became the basis of modern scientific work.

Alexis Pedrick: When vision became king in the 17th Century, it created barriers to entry for science. If you wanted to contribute to the collective understanding of the world, you had to be privileged. Because you needed money to afford a microscope and the training to use it. But there was another layer of gate keeping. There were also firm ideas about what kind of person should be trusted to create knowledge.

Jessica Martucci: In order to trust somebody’s eye, you have to trust them as a person. Right? So, you have to believe that they have no bias or interest in not producing objective information. And so the kind of people who were invited to produce scientific knowledge back in the 17th Century are for the most part, s- very privileged people. And this idea that there were sort of trustworthy knowers and they were the ones who were privileged enough to produce knowledge I think continues to shape the way we think about science today.

Lisa Berry Drago: Chapter two. Who are the trustworthy knowers?

Alexis Pedrick: Judith Summers-Gates-Gates wanted to be a scientist from a young age, but it wasn’t easy. She had to rely on the same kind of imaginative work arounds she used when she was a girl scout. She also had to convince other people that they could trust her. Over and over and over again.

Jessica Martucci: When she was first starting out trying to get jobs, she had a rough time because people would take one look at her and say like, “How could you possibly do this work?”

Alexis Pedrick: And their disbelief was two-fold. It wasn’t just that she was vision impaired. She was also a woman who dared to do science in the 1970s. And this was her first offense. Because it was usually the first thing employers notice. She went on one interview at a petroleum company in Philadelphia in 1978. It started off terribly and then got worse.

Judith Summers-Gates: The gentleman doing the interview took one look up and down and said, “You’ve got to be kidding.” I mean, literally this is what the man said. And it’s like, “Okay, uh huh.” And as we spoke it became more and more obvious that he, they did not want women in this position. Because he kept asking questions that were based mainly on physical ability and strength and size and you know, like, and he, and he said, “You’re short.” Uh huh. You don’t have a ladder in this entire facility? I’ll bring one. What’s the problem? And as for me, I had a little tiny telescope that I used to use to look at street signs and things when I was wandering around to get my bearings and he said to me, “What’s that for?” And I, and I told him. I said, “This is my telescope. I use it to look at signs and whatnot.” And he said, “You can’t see either?” Well, I found my way here, didn’t I? You know, excuse me. But he was, he was just … and he finally said, he just got up and said, “This interview’s over,” and he got up and just left. He left the room and he walked out and I was sitting there. I’m like, “Mm-hmm [affirmative]. Okay. So, what do we do?” And I got up and I, I wasn’t, I was annoyed but I wasn’t yelling. And I got, I walked out to where his assistant, his secretary was and at that time, she was still called a secretary. And I asked her. “What does this gentleman’s schedule look like for the rest of the morning?” And she says, “Oh, he’s open for the next hour and a half.” Oh. Good. Thank you. So, I got up and I, there and I walked back in and sat back down again in his office.

Jessica Martucci: And she refused to leave and so eventually, he did come back in and do the interview. She explained, you know how she does what she does with the vision that she has.

Judith Summers-Gates: We argued or carried back and forth verbally and for every reason he would come up with, I would come up with an answer saying not an issue. And I finally got to the point where I said to him, “Look. I don’t know about your other employees but I don’t send my chromosomes to work without me. The rest of me shows up with them. So, if I’m all here and the brain is up here and it’s not connected to the chromosomes. Why can’t I do this job?” And he just sat there. And, and you could tell that he was finally defeated. He was just done in. And, and he looked at me and he says, “What do you want?” I said, “The job.” [laughs] He says, “Well, we’ll have to talk about it.” Well, we are talking about it. [laughs] and I just wouldn’t leave this man alone.

Jessica Martucci: And then she ended up getting offered that position, but she turned it down as a matter of, like, principal, to basically say, like I don’t need to work in a place where people like me are going to be discounted right off the bat.

Judith Summers-Gates: And that kind of had to be the way I approached a lot of things in my life. Saying, “No, you’re not putting me off to the side for some irrelevant reason. You better have a good reason and it better stick.”

Alexis Pedrick: The man who interviewed Judith did not see her as a trustworthy knower. He saw her as a woman, strike one, who could barely see, strike two. It didn’t matter to him that she was an accomplished graduate student who made it to the interview on her own. All he saw was that she needed a telescope to get there and she’d need it to do the job too. And to him, that was unacceptable.

Jessica Martucci: So by, sort of requiring scientific knowledge to be produced in this very specific way that privileges vision, you know it’s very obvious that that is excluding certain kinds of people right from the get go. Talking to people who are actually working in the sciences who have these different perspectives because they are blind or low vision, it just kind of makes it very clear that, oh right, it doesn’t, doesn’t necessarily have to be this way. And they are making knowledge and there are other ways of knowing and these people are clearly, you know, evidence of that.

Alexis Pedrick: We started out this episode talking about microscopes and how these tools became the symbol of elite scientific knowledge production. If you knew how to use one to see something that was otherwise too small to see like, say, a flea, you were pretty cool, right? You could draw conclusions about that flea that other people couldn’t. So, it’s a little ironic that when a low vision person like Judith uses a telescope outside the lab it becomes problematic. When she walked into that interview holding a telescope, it made the hiring manager question her reliability. Her trustworthiness. Even though she was using it for the same reason to make something visible that she couldn’t otherwise see. Wearing glasses to correct your vision, totally socially acceptable. Magnify things any more and you get in trouble. It’s all a matter of degree.

Lisa Berry Drago: Chapter three. Doing it differently isn’t doing it wrong. No matter what they say.

Alexis Pedrick: When vision impaired scientists or future scientists hit roadblocks with teachers or employers, it often comes down to an assumption that things have to be done in a specific way. And a lack of imagination about how the same results might be achieved differently. Amy Slaton is a history professor at Drexel University who studies disability. She recently analyzed the experience of a blind chemistry student at a large state university. I’m being vague on purpose. The identity of both the student and the school are anonymous for legal reasons. The student was assigned an assistant to interpret things for her. They would watch the lecture and relay the visual information to the student.

Amy Slaton: And so, in some ways, that just sounds like what every disabilities office is mandated to do by law, right? Which is create equivalent educational experience for disabled students but of course, what she bumped into because it was science [laughs] was the idea that there is an expert sense of what equivalence is. There’s an expert sense among, you know, scientific authorities including instructors and people of very, you know great accomplishment in these field of what counts as the scientific learning. What counts as experiment, what counts as observation, what counts as analysis, right? Each of the things that are customarily said to add up to doing science or learning science, right? Well, we, experts know them when they see them. Right? They know what that counts as. It does not count as your own work or your own discovery if someone else is telling you what they are seeing.

Alexis Pedrick: And there were other obstacles. The professor told the student she couldn’t take the lab based final because she wouldn’t be able to read the level of liquid in a test tube with her own eyes, emphasis on her own eyes.

Amy Slaton: To which she responded by having the glass blowing shop at the university etch calibrations onto the outside of the tube, right? So with her own ingenuity she kind of said, “Yes I can.”

Alexis Pedrick: But it kept going. The university told her she couldn’t perform the experiments in the final because of liability issues. Which is a common hurdle for people with disabilities. This was their reasoning.

Amy Slaton: If you can’t see, you can’t meet the safety requirements of this lab. It’s not our problem. It’s not our fault. It’s nobody’s fault but liability says we must have, you know our students be safe. You won’t know how far away you are from, say, you know, the burners or the acid. Right? And she, of her own accord, went and got floor mats, I think from Target that, were, placed on the floor and she knew that if she was on the mat, which she could feel with her feet, she was a safe distance from the surface. So, in each of these cases, whether they derive from the, what I would call an epistemological objection to her activities because they weren’t true learning or true discovery or true um, you know, rigor or if they were institutional almost liability concerns like the safety ones, she brought something to the situation that added up to participation.

Alexis Pedrick: The birdseed and telescope. The floor mats from Target. Amy Slaton says that all tools and technologies like these are essential to doing science with a disability. But when scientists with disabilities use them, they often make other people question the validity of their work.

Amy Slaton: I think they kind of get us stuck in the notion that there’s real science and then there’s a substitute or there’s a alternative.

Alexis Pedrick: It’s not that the answer they’re getting at is wrong. It’s that they’re not doing it in the usual way.

Amy Slaton: That’s all it is. It’s what we’re used to. It’s what’s become credible. We know with science because there’s a right way to do it. It’s got a right way, right? You don’t measure the temperature of lava with, your bare foot if you’re a volcanologist. You have to have a calibrated something. A calibrated thermometer or a geothermal, you know, mapping sys- right? There’s one right way. And that is, that’s the essence to me of a lot of Western science.

Lisa Berry Drago: Chapter four. How do we know what we know and how might we know it differently?

Jessica Martucci: The fact that you can do chemistry without sight I think is, it just kind of blows the whole idea about vision being a kind of necessary part of producing scientific knowledge out of the water.

Alexis Pedrick: Over and over again, low vision scientists like Judith Summers-Gates-Gates have not only proven that they’re each as good as any other scientist, they’ve shown that they bring unique qualities and abilities to the table. And over the years, some people have recognized that. Even if it sometimes took them a minute. When Judith went to interview for another job, she found the manager underneath a piece of machinery. Picture a mechanic under a car.

Judith Summers-Gates: And I stopped down down there in front of, near where he was and I said, “Hi, I’m looking for engineering,” and, but he didn’t hear me at first because the noise he was making. And he just looked over and he saw feet, you know ankles. He’s like, “Ankles? No. There should be pants.” And we’re, I’m seeing ankles. And he said, “Then you know the secretarial area is up that way.” I said, “No, sir. I’m not looking for the secretarial area. They sent me from there to you here. I’m here for the interview.” And he’s like, “What?” And he sat up so fast, he banged his head on the machine. [laughs] So this was a huge surprise to him. He recovered well, both from the bump and the shock. As we, as we were sitting there having the interview, he kind of, he was kind of I don’t know what to do with this. And as we were talking, somebody else came in from the laboratory side with a sample of one of their products that they were having a problem with at the time. And, and they were holding that and they were discussing this and they were making tags, tickets and labels of various types and this was for a clothing label. And they were talking about why this product was not working and what they were going to do trying to fix this. And I just blurted out, “Why does that smell so terrible?” And they looked at me and he says, “What?” I said, “That thing in your hand. It smells awful. What’s-” They said, “It does?” I said, “Uh huh.” And they both looked at each other, they said, “Wait a minute. Stay there.” And the person ran back to the lab, came back with some other samples of something else and said, “What about this?” I said, “No, it’s totally different.” And then their light bulb came on. They realized that what I was smelling was the coding breaking down on the surface of the tag product and that was what was causing their problem. But they, since they were in that atmosphere so much, they were oblivious to it. They were not picking up on it, but me “ew that wreaks.” Take it outside please before my eyes start watering. And they’re showing me the regular product which was passing all the quality assurance things. I’m like, “Nope, totally different. This one’s, this one’s fine. That one has something wrong with it.” And everybody’s just like, “That’s it. That’s it. You’re hired. Don’t go anywhere. Stay right there.”

Alexis Pedrick: We talked to another blind chemist for this story. Mona Minkara. Mona is a millennial, and while she didn’t have to navigate such blatant sexism as Judith Summers-Gates in the 1970s, she did experience the same doubt and distrust from teachers and employers. In high school, she demanded to take an advanced biology course. Even though the head of the science department told her she’d fail if she did.

Mona Minkara: So then, I went to the first day of class and the teacher told me that I don’t belong in her class. And I said, “Well, I’m still going to be here.” And then she said, “I’m not going to adjust my teaching to accommodate you.” And I said, “Okay.”

Alexis Pedrick: Mona got the best grade in the class and at the end of the year, the teacher apologized to her. She went on to graduate school in computational chemistry and found people who not only accepted her, but recognized that her blindness actually helped see things that other people couldn’t. In graduate school, she was studying a gut bacteria called H. pylori that infects about two thirds of people around the world. It can lead to ulcers and sores in the small intestines and there’s no cure for it. While analyzing the proteins in the bacteria, Mona could pinpoint patterns it made in the intestines. And she created a molecular computer simulation of how it behaved. Usually, scientists rely on watching videos of the proteins to make these simulations, but that wasn’t an option for Mona.

Mona Minkara: I couldn’t just see the movie of the protein moving, right? That I had to plot, plot it mathematically and just by doing that step, even though it’s a known step, I didn’t do anything that was, like, extraordinary, but by using that as my main mode of data collection, I was able to observe patterns missed by sighted people.

Alexis Pedrick: The simulation helped with the understanding of the bacteria. And that led to the creation of a drug to treat it. This moment changed how she viewed her blindness. From a disability to an advantage.

Mona Minkara: And so when I did this, I didn’t see it as an advantage. I saw it as just finding a workaround, um, to keep up with my peers. It wasn’t until later and my, um, post-doc advisor, you know when I got my PhD, I got a job offer from Professor J. Ilja Siepmann, and immediately, like he just offered me a job. No questions asked and I remember being like, “Why do you want me in your lab? Do you know that I’m blind? Do you know that I do things slower? Do you know XYZ?” And he was like, “Yes. But none of that matters because you think differently and you’re going to be able to solve problems, um, that nobody else has solved and he, he gave me this example as an example.” He was like, “Look, you did this,” and, and because of my conversation with him, I recognized the advantage of that. Like, I, I almost hadn’t re- recognized that advantage until I talked to someone who did see my blindness as an advantage. And that changed my perception of what I could contribute to the world. That was a huge shift for me because up until that point I was doing science because I loved it, right? But I felt like I was running to catch up. And in some cases, I, I kind of am because the world is completely geared to sighted people. But now I have this, a sense that maybe I have like, you know, a secret tool in my pocket that I could use. And that is because I, I’m inherently a problem, solver and inherently have to do things differently.

Lisa Berry Drago: Chapter five. Who gets to participate in science?

Alexis Pedrick: The American Chemical Society is the largest scientific society in the country and Mona Minkara sits on the Chemists with Disabilities Committee. When we asked her to put us in touch with some of her peers, she could only name three chemists who are blind.

Mona Minkara: There really aren’t many of us and we end up, like meeting whenever we have, like a conversation about science and disabilities. It’s just us. [laughs]. Like-

Alexis Pedrick: Why aren’t there more blind chemists? Mona says because it’s still a field designed for sighted people and the only way it’ll change is if more blind people are on the inside.

Mona Minkara: Honestly, I was discouraged to be a scientist as a blind person. It was considered impractical. This is not an accessible world. It is very visually based. Especially like a world like computational chemistry, right? Like it’s all modeling and it’s all, like structure. Visual information. And so, and that is how we teach it. The main mode of relaying scientific information in the world today is visual and we haven’t figured out way to make it accessible in an efficient manner and that is problematic, right? So, that it’s a catch 22. And then there aren’t people working on this problem because there’s not enough people, you know to work on this problem. Because the, the demand is low. You know, it’s a catch 22, right? [laughs] like, we need more technologies. There’s no incentive for more technologies because nobody’s using, you know there’s very few people that need them. Like, it’s just a cyclical cycle and it needs to break. It needs to change.

Alexis Pedrick: Mona and Judith have proven that it’s possible to do science without sight. But they’re still working within a system that wasn’t designed with them in mind. Someone like Mona who doesn’t fit the mold is seen as an inconvenience. Instead of seeing the system itself as flawed and in need of change.

Mona Minkara: I got on to multiple graduate programs, right? For chemistry. And I got into one of the best graduate programs in the country and I reached out to the disabilities office and at the time, they basically, the person who answered, I was like, “I need, like assistance or whatever. Like access assistance.” And the person was like, “We don’t provide that.” And I was like, “Well, how do you expect the blind person to study science then?” You know, and they were like, “Many people do that and they’re fine.” I was like, “Really?” You know, like this person was being very deffensive and then, like, they hung up the phone and then their boss called me like literally five minutes later and they’re like, “We’ll provide you everything that you need from, you know, legal perspective.” And I was like, “Okay,” so I’m getting, like legalese, you know, given to me. And then like a day later, I get a phone call from a person who was in charge of the deaf and blind students in the disabilities office at the school and he was like, “Do not come here. They will not provide you what you need.” And this is, like verbatim something that was told to me. And he was like, “I’m retiring soon and they’re not even replacing me.” He told me this. So, the system the problem is the law states that there should be reasonable accommodation. But then the interpretation of reasonable accommodation is what becomes the question and the battle. But I made sure after my undergrad that I went to institutions that were going to give me what I need without a battle, without a fight, you know? I chose University of Florida because they gave me the red carpet. The disabilities office was amazing there. And I succeeded because of that. I didn’t have time to not just fight for what I need and then fight to also learn science. You know, I, I didn’t have that capacity. So, I didn’t need to fight for what I needed. I got what I needed. And the same with being a post-doc. Like, this is key. Right? I applied to positions to be faculty at over, like around 50 institutions last year. I got emails from a couple of institutions literally saying my CV was impressive but they could never accommodate somebody like me.

Mona Minkara: If I wanted to become a motivational speaker, I believe I’d be able to do that tomorrow, right? I could just put out there and be like, “I’m a blind scientist. I’m a blind scientist. Like, you know tokenize this possibility.” But the reality is for me is that I am a human being who happens to be blind and loves science. I want to contribute to the scientific community with solving problems and part of that could be creating more tools and technologies to allow me to solve more scientific problems.

Alexis Pedrick: Judith and Mona have become successful scientists and that’s a wonderful thing. But if you only focus on the inspirational side of the story, that gets into “supercrip” territory. And that’s bad. Supercrip is a new term to us. Crip is the reclaiming of slur, kind of like queer. And the super part frames disability as a personal struggle that can be overcome like you’re some kind of superhero. This framing distracts from the systemic problems that people who have disabilities actually face.

Jessica Martucci: It just kind of individualizes disability and puts it on that person to kind of create their own way out of whatever social oppression they’re experiencing because of their disability.

Alexis Pedrick: And besides being unfair, all of those social barriers get in the way of science. Because the important part of making knowledge isn’t how you do it. It’s what you come up with at the end.

Judith Summers-Gates: Being a scientist, you have to be able to interpret your data, collect your data, manipulate, not, not in terms of fudging your data, but manipulating it, using it and whatever tools you need to do and use to get to that process, that makes you a scientist. Regardless of how you do it. Whether you could see, look through a telescope or whether you can look through a microscope or whether you can go out in the field and pick up some plants. However it was you gathered your data and your specimens and manipulated and used them, that makes you a scientist. The m- the how you do it is not important. It’s the what you do with it when you finish it.

Lisa Berry Drago: Thanks for listening to this episode of Distillations.

Alexis Pedrick: Remember, Distillations is more than a podcast. It’s also a multimedia magazine.

Lisa Berry Drago: You can find our video, stories and every single podcast episode at distillations.org and you’ll also find podcast transcripts and show notes.

Alexis Pedrick: You can follow the Science History Institute on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for news and updates about the podcast and everything else going on in our museum, library and research center.

Lisa Berry Drago: This episode was produced by Mariel Carr and Rigo Hernandez.

Alexis Pedrick: And it was mixed by James Morrison. Special thanks to our former colleague Jessica Martucci for leading the Science and Disability Project at the Science History Institute and for giving us indispensable guidance as we shape these episodes.

Lisa Berry Drago: The Science History Institute remains committed to revealing the role of science in our world. Please support our efforts at sciencehistory.org/givenow.

Alexis Pedrick: For Distillations, I’m Alexis Pedrick.

Lisa Berry Drago: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago. Thanks for listening.