Amid all the logistical headaches of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, one huge challenge involves the cold chain. The cold chain is a network of freezers and refrigerators that keep vaccine doses at the consistently cold temperatures they need to stay viable. Though complicated, this is all doable in the 21st century. But how did the world’s very first vaccine, created for smallpox in 1796, make it around the world? Listen to the surprising answer in a new podcast collaboration with best-selling author Sam Kean, about how the vaccine depended on live carriers—specifically, orphan boys.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

“Delamine” by Blue Dot Sessions

“La Flecha Incaia” by El Conjunto Sol Del Peru

All other music composed by Jonathan Pfeffer

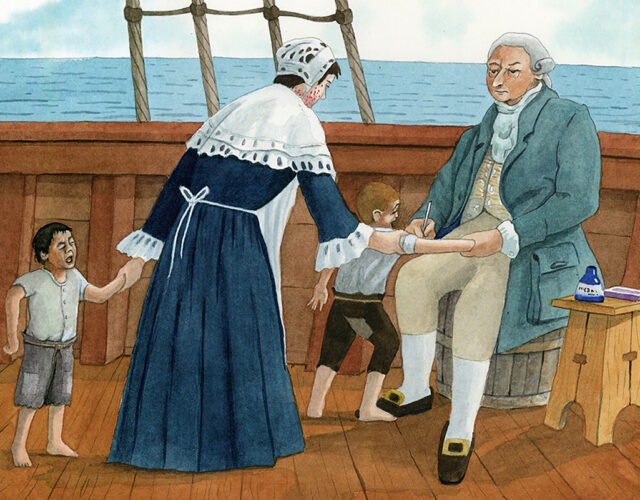

Image by Carles Puche, Mètode Journal

Transcript

Alexis: Hello, I’m Alexis Pedrick.

Lisa: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago. And this is…The Disappearing Spoon—a new podcast from the Science History Institute!

Alexis: Don’t worry, Distillations isn’t going anywhere! We’re just expanding. We’ve teamed up with best-selling author Sam Kean to produce a second podcast all about little-known stories from our scientific past. Welcome Sam!

Sam: Thanks for having me! I’m thrilled to be here.

Alexis: We’re very excited to have you.

Lisa: We’re going to be releasing Distillations and the Disappearing Spoon on alternating schedules, so you’ll never lack for history of science content! You’ll still get the in-depth narrative stories you know and love from Distillations, and now you can get your nerd fill from the Disappearing Spoon too.

Alexis: For the next ten weeks you can find Disappearing Spoon episodes in our feed and on our website, distillations.org. After that we’ll be releasing a full season of Distillations episodes. So without further adieu, we present: the Disappearing Spoon…

Sam Kean: Amid all the logistical headaches of delivering a coronavirus vaccine, one big challenge involves the cold chain. That is, the need to keep vaccine doses at consistently cold temperatures, to keep them viable.

But the more I heard about the cold chain, the more I started wondering about something else. The very first vaccine was produced all the way back in 1796, for smallpox. That was long before refrigerators and dry-ice machines. So how did doctors actually deliver vaccine doses way back when without keeping them cold? What was the vaccine supply chain like in 1800?

The answer shocked me. Today, we rely on refrigerators and Styrofoam, not to mention trucks and planes. In the early 1800s, doctors used a so-called “living transmission chain” instead, which involved keeping the virus alive in animals.

And what animals did they use? Juvenile Homo sapiens—that is, little human beings. Specifically, the world’s first global vaccine supply chain depended critically on orphan boys.

<MOOING> Modern vaccines started with the British doctor Edward Jenner. In short, Jenner observed that milkmaids who caught a disease called cowpox never came down with the far deadlier disease of smallpox. As we would say today, cowpox gave people immunity to smallpox.

So in 1796, Jenner started giving people cowpox intentionally. Most famously, he gave cowpox to eight-year-old James Phipps, the son of his gardener. He then exposed little James to smallpox several times. But James never caught it. Thanks to cowpox, James was immune.

We now call Jenner’s process of intentionally exposing someone to a virus a vaccination, after the Latin word for cow, vacca. And it’s hard to overestimate how big of a breakthrough this was. Vaccinations have arguably saved more lives than any discovery in any field in history.

But at the time, Jenner’s breakthrough actually introduced another dilemma. Doctors now knew how to make people immune to smallpox. But how could they actually deliver vaccines to people who needed them?

Within Europe, spreading vaccines was straightforward. People with cowpox developed pustules on their skin—sores that filled with fluid called lymph. First, a doctor lanced the sore, and collected the fluid. Then the doctor turned to the person to vaccinate and scratched their arm or leg to break the skin. Finally the doctor rubbed the lymph into this scratch. When the lymph soaked in, this second person was now vaccinated.

Doctors could also transfer lymph from town to town. They did so by smearing lymph on a silk thread or ball of lint and letting it dry. Then they sealed the thread or lint in wax or glass to preserve it. After walking or riding to the next town over, they mixed the dried lymph with water to reconstitute it, and then started scratching people’s arms and legs again. Pretty straightforward.

The trouble started when doctors tried to vaccinate people over long distances. Dried lymph could lose its virulence traveling even from London to Paris, just 215 miles. Things got especially tricky transferring lymph across the ocean.

At the time, smallpox was probably the scariest disease on earth. It covered people’s skins with frightening sores. Hundreds upon hundreds of pustules erupted, covering every square inch of the body. In the worst outbreaks, ⅓ of people died. Even survivors were often stricken blind, and left with ghastly scars.

In European colonies abroad, death rates were even higher. The Americas had especially apocalyptic outbreaks, with half or more of all people dying. Smallpox was in fact a decisive factor in the downfall of the mighty Incan and Aztec empires in the 1500s. Otherwise, a few malnourished Spaniards with crappy guns never would have conquered them.

For three centuries, then, smallpox had been ravaging European colonies abroad. So when Jenner’s vaccine popped up, European governments tried transporting threads of dried lymph across the sea.

Every so often this worked. A thread with encrusted lymph did reach Newfoundland in 1800, and vaccines began trickling down North America from there. In the majority of cases, however, the dried lymph was impotent after months at sea. Viruses are fragile and cannot live outside a body for very long.

Spain especially struggled to get dried lymph to its colonies in Central and South America. So in 1803, the Spanish king Carlos IV demanded that his ministers find a better way.

Now, it’s easy to be cynical about the motives here. The king’s ministers, especially in the royal treasury, were hardly humanitarians. Mass death was simply bad for business abroad. And don’t forget, while they were trying to save lives, Spain had also introduced the disease in the first place.

That said, King Carlos himself was sincere. Carlos has gone down in history as a weak and feckless fellow who later got steamrolled by England and France. But Carlos had lost both a brother and a daughter to smallpox, and cared deeply about stopping it. So he ordered his medical advisors to come up with a plan.

Their answer was simple. A chain of orphan boys.

They proposed taking a few dozen boys and putting them on a ship. Right before departure, a doctor would give two of them cowpox. After nine or ten days at sea, the pustules on their arms would be nice and ripe. A doctor on the ship would then lance the sores, and transfer the fluid to the next two boys in the chain, scratching it into their arms.

Then the doctor would wait nine or ten more days, for the second pair to develop ripe pustules. Then those sores would be lanced, and the fluid transferred to a third pair of boys, and so on.

They proposed using pairs of boys just in case one of the two didn’t develop sores. That way, they had a backup, and the chain would remain unbroken.

Overall, with good management and a bit of luck, the ship would arrive in the Americas when the last pair still had cowpox sores to lance. A medical team could then hop off the ship and start vaccinating children onshore, since children were most susceptible to smallpox.

King Carlos approved of the plan.

Now, of course no one asked the orphan boys whether they wanted to participate. They were foundlings, living in state-run orphanages, and had no power to resist. But, King Carlos promised them free education in the colonies, plus the chance at a new life there with an adoptive family. It was a far better shake than they’d get in Spain.

Plus, Carlos promised to stuff them with food on the journey over and give them new, warm clothing. Why? So the boys would look healthy and hearty when they arrived. Because think about it. If the boys arrived in the Americas looked sickly and ragged, no parent there would ever let fluid from their arms be injected into children. Caring for the orphans was both good medical policy and the right thing to do.

The orphan voyage was officially called the Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition. The doctor in charge was Francisco Xavier de Balmis. At age 49, Balmis was ideal for the job. He’d spent time in the Americas collecting plants, so he knew the scene there. He’d also administered vaccines in Spain.

Furthermore, Balmis was wildly ambitious, and wanted to be famous. So he had strong motivation to see the expedition succeed.

The voyage began on November 30th, 1803, in a 160-ton corvette called the Maria Pita. Twenty-two orphans were onboard, ages three to nine. In addition, Balmis had eight nurses and medical assistants. There was also a single woman onboard, Isabel Zendal Gómez. She was the rectoress of the orphanage from which they’d plucked the boys. She’d come along to comfort them.

And her care would prove vital. Despite the good food and warm clothing, it was still wintertime on the Atlantic Ocean—cold and choppy. The boys were no doubt homesick and seasick. Plus, plain old sick from cowpox.

Worst of all, cowpox is itchy. You want to scratch the pustules. But the boys couldn’t. Scratching them would break the pustules open, and spill the precious fluid.

So day and night, the nurses onboard watched the boys, snapping at them whenever they scratched their arms. Imagine trying to explain all this to a cold, lonely three-year-old. <WAILING> Isabel Zendal Gómez had her work cut out for her.

But she and Balmis kept everyone on track. They eventually arrived at Caracas in modern Venezuela in March 1804.

And not a day too soon. There was just one pustule left on the arm of a single boy. But it was enough. Balmis immediately started vaccinating onshore. And he proved a tireless worker.

Now, estimates vary for all the numbers you’re going to hear. But by some accounts, Balmis vaccinated 12,000 people in and around Caracas in just two months.

Equally important, he set up a local vaccine board to monitor outbreaks. The board also kept records, trained vaccine technicians, and educated people. It was a full-on public-health approach.

Now, after a few months in Venezuela, the Royal Vaccine Expedition split into two parties. One party was led by Balmis’s top deputy, Dr. Jóse Salvany.

Salvany’s party took some encrusted lymph and headed south to vaccinate people in what’s now Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia.

It was a hell of a journey. Salvany’s team had to hack their ways through jungles, and cross the forbidding Andes mountains. All while keeping the precious threads of lymph safe.

But it was worth it. In most villages people were thrilled to see them—they were hailed as medical saviors. Cathedral bells rang, and priests said masses of thanksgiving. Some villages even shot off crude fireworks <BURST> and held bullfights in their honor.

Over the next few years, Salvany’s team vaccinated up to 200,000 people, saving countless live. Sadly, though, Jóse Salvany could not save himself. The arduous journey across jungles and mountains ruined his health. He lost an eye to disease and later collapsed from exhaustion. He ended up dying of tuberculosis at age 34—a medical martyr if there ever was one.

Meanwhile, Dr. Balmis was crossing Mexico, where he vaccinated up to 100,000 people. Halfway across, he dropped off the orphans with their new families in Mexico City. Then he headed to Acapulco on the Pacific Ocean coast. There, he prepared a journey to the crown jewel of the Spanish colonies—the Philippines.

In Acapulco, Balmis picked up a few dozen more boys. These boys weren’t orphans, but came from poor families. So Balmis paid money to hire the boys, essentially renting them as vaccine mules for the journey to Asia.

Now, Asia actually had its own ancient methods to prevent smallpox outbreaks. These methods included peeling skin scabs off smallpox victims, pounding them into powder, and snorting them. But they worked surprisingly well. You can hear all about these methods in a bonus episode at Patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

The bonus episode also includes the story of the fiercely independent woman who first introduced inoculation into Europe—and did so decades before Edward Jenner. It’s an incredible tale. All that and more bonus episodes at Patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

Overall, however, vaccines were medically superior to traditional prevention methods in Asia. So Balmis set off with the new boys for the Philippines in February 1805. The rectoress Isabel Zendal Gómez was once again on hand to tend to the boys.

The ship arrived April 15th, and within a few months, Balmis’s team had vaccinated 20,000 people. Things went so well, in fact, that Balmis went a bit rogue and sailed up to China in the fall of 1805 to vaccinate people there.

Within China, he ended up working with British colonial officials—which was remarkable, considering that Spain and England were technically at war. In fact, at that very moment on the other side of the world, the British admiral Horatio Nelson was humiliating the Spanish fleet at Trafalgar. But Balmis didn’t let politics interfere with his medical mission.

Eventually, Balmis wound his way back to Spain, arriving in Madrid in September 1806. Just like he wanted, he got to be famous. King Carlos declared him an international hero. And it’s hard to disagree with that assessment. Edward Jenner himself said, “I don’t imagine the annals of history furnish an[other] example of philanthropy so noble, so extensive as this.”

Scientifically, it was pretty amazing, too. Over the past year, humankind has cooked up a vaccine for coronavirus and delivered it to millions of people—record-breaking speed. But Balmis’s achievement was no less staggering.

Despite having zero refrigeration and no modern transportation, he managed to spread Jenner’s vaccine across the entire world in less than a decade. His crew directly vaccinated hundreds of thousands of people, and saved millions more.

Historians have called the Balmis expedition the world’s first modern vaccine campaign. And while the mission certainly didn’t wipe out smallpox, it paved the way for the elimination of smallpox by the 1970s. It remains the only human disease ever eradicated.

But just like Jenner needed young James Phipps for his experiments, Balmis never would have succeeded without those nameless, all-but-forgotten orphan boys. We can praise the wonders of the modern vaccine cold chain. But in fighting one of the worst diseases in history, it was this warm chain, of small helpless brave boys, who proved the real heroes.

This is the Disappearing Spoon podcast, brought to you by the Science History Institute. Find out more about their library, museum, and multimedia magazine at sciencehistory.org.

Make sure you check out the Science History Institute’s other awesome podcast, Distillations. You can find their in-depth narrative stories and interviews about everything from Space Junk to Sex, Drugs, and Migraines anywhere you get your podcasts, and on their website: Distillations.org.

You can find more incredible stories from my books at samkean.com. You can also book me as a speaker at your school or event.

If you like this podcast, please support it at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. It costs as little as seven cents per day. You can also get bonus episodes and signed books.

Please spread the word to others as well, and subscribe in iTunes, Stitcher, or other places.

This episode was written by me—Sam Kean. It was mixed by Jonathan Pfeffer, and produced by Mariel Carr and Rigoberto Hernandez.

Thanks for listening…