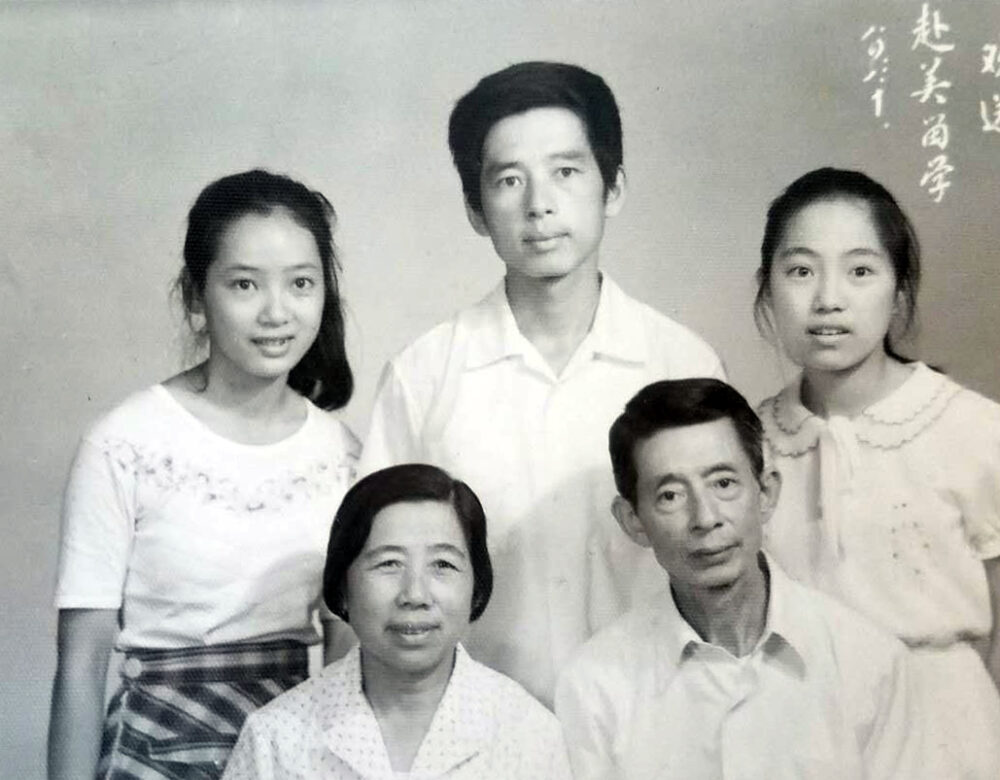

Yue Xiong is a microbiologist who immigrated to the United States from China to complete his doctorate in 1989. He is the chief scientific officer of pharmaceutical company Cullgen and was a professor of biochemistry and biophysics at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Xiong’s father, Shenggao, was a forestry scholar who was sent to labor camps, first during Mao’s Anti-Rightist Campaign and then during the Cultural Revolution. This article follows Yue Xiong’s quest for education and is based on an interview from the Science History Institute’s oral history archive conducted in 2000 by historian William Van Benschoten.

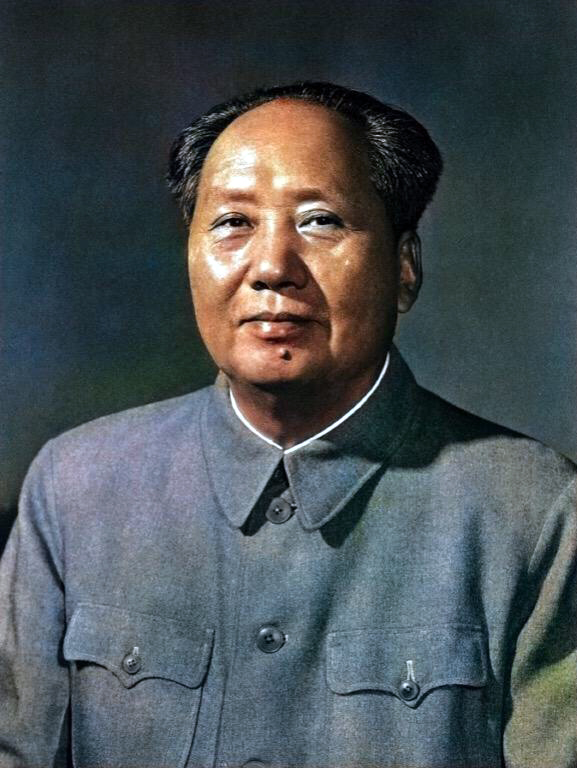

Mao Zedong was born in Hunan province in 1893, the son of a wealthy peasant. His father had served in the army and managed to save enough money to buy some land. Within a few years of Mao’s birth, he had acquired three and half acres of rice paddy and brought on two workers, who received little more than a daily ration of rice for their labor. Mao’s father was a careful, scrupulous man with money—miserly, by Mao’s account—and soon became one of the richest men in Hunan province—a landlord with a stockpile of roughly 3,000 silver dollars (a great fortune at the time). His father’s tight-fisted attitude toward money and family would influence Mao for the rest of his life. “I learned to hate him,” Mao said later. Still, his father took the trouble to send him to school, an affordable expense for a peasant as well-off as Mao’s father but still no small sacrifice—yearly tuition at the grim, one-room schoolhouse accounted for roughly half a year’s wages for an average farmhand.

Although Mao gave his father scant credit for it later, the education he was afforded would shape the fate of the country. After the Communist Revolution of 1949, Mao was determined to eliminate inequality. He paid special attention to the plight of Chinese women, banning the practice of foot binding and establishing women’s right to an education and to vote. He also reformed China’s marriage law, replacing a system in which brides were often bought and sold with one that required both parties’ consent and gave women the right to divorce.

Realizing other reforms, such as the redistribution of property, was more complicated.

What makes a peasant wealthy? The line demarcating self-sufficiency from prosperity wasn’t always easy to define. As the Communist Party set out to implement its land-reform policy after the revolution, disagreement grew over how to deal with the land-owning peasants. Some, such as “Uncle Shitcrock,” a landlord with massive holdings in Xunwu County, were quite clearly enemies of the people. Poor peasants often paid more than half of their income in rent to landlords and a bad harvest could send one quickly into bankruptcy, forcing families to sell their sons to pay their debts. “At this moment the biological parents of the boy always weep and wail,” Mao wrote in a report on the peasant situation in southern Jiangxi.

But most landowners had significantly more modest holdings. Even Mao admitted that many small landlords were progressive, rather than reactionary.

As the Communist Party looked for a way to equitably distribute land, Mao argued for the simplest solution—seize all the land and redistribute it equally. Allowing any private property to remain would fundamentally undermine the entire endeavor.

Although some advocated lenience for rich landowners who treated tenants with dignity, Mao said they were “the bourgeoisie of the countryside” and “reactionary from start to finish.” Rich peasants accounted for such a small number of the overall peasantry that Mao believed carving out special regulations for them was irrelevant.

Just a few years later, this policy was judged insufficiently harsh by other party leaders. Party officials argued that landlords needed to be wiped out entirely and rich peasants entirely dispossessed. Mao worked to develop a strict metric. As Philip Short wrote in Mao: A Life,

Mao cautioned that these metrics should be applied carefully, on a case-by-case basis, but this was a pipe dream. As Short points out, the more landlords and “rich peasants” local municipalities executed, the more land there was to go around. Long-standing grudges and petty grievances suddenly could become a matter of life or death.

Among those swept up in this witch hunt was a young forestry scholar from Nanchang City. Shenggao Xiong came from a family of landholding subsistence farmers. The family wasn’t wealthy—they had been forced to sell most of their land near the end of the revolution to bury Shenggao Xiong’s father and grandfather—but the plot they still owned was enough to put them in the bad graces of the Communists, who labelled them anti-revolutionary. Despite these obstacles, the family managed to secure an education for Shenggao.

Mao had always been deeply suspicious of intellectuals, but after uprisings in Poland and Hungary against the Soviet Union in 1956, he began to take a different tack. The problem, he gathered, was not just a failure to eliminate counterrevolutionaries, but a failure to govern effectively.

“There are certain people who behave as if they can sit back and relax and ride roughshod over the people now that they have the country in their hands,” Mao said. The Communist Party “must be vigilant and must not allow a bureaucratic work-style to develop. We must not form an aristocracy divorced from the people.”

His answer was the Hundred Flowers Movement, a short-lived campaign (1956–1957) to open up speech within civil society. Other party officials warned against it, but Mao pushed forward. “Fear is no solution,” he said. “The more afraid you are, the more ghosts will come to visit you. . . . We can’t just stifle everything all the time.”

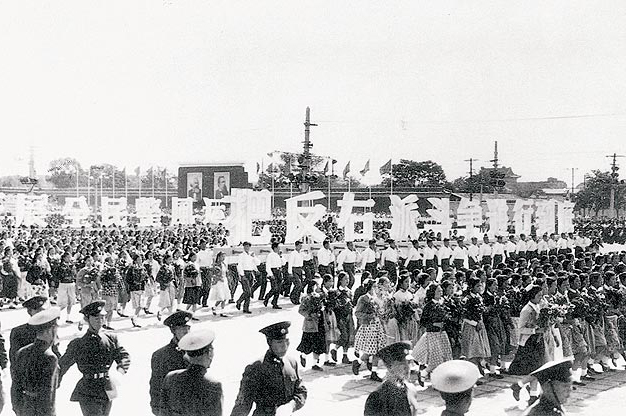

Within just a few months mass protests again broke out at universities and high schools. In Wuhan, even middle school students took to the streets and stormed government offices. A “Democracy Wall” papered with anti-Communist material sprang up at Beijing University.

It soon became more than Mao and other party officials could stomach. Faced with evidence that they had become irrevocably divorced from the people, they cracked down on anti-revolutionary “Rightists,” who were arrested and shipped to the countryside for reeducation.

Shenggao Xiong had made the mistake of airing what he thought were innocuous comments about improving efficiency at work. That tossed-off criticism, however, combined with his education and a politically inconvenient family background, sealed his fate.

“The whole thing became letting [people] speak and then saying, ‘Well, I caught you,’ ” his son, Yue Xiong, told interviewer William Van Benschoten in 2000. “Six days after I was born, he was handed a piece of paper saying he was stripped of his profession and his job. He was supposed to be sent to prison.”

Instead, Shenggao was shipped off to a labor camp, along with an estimated 1 to 2 million other alleged political subversives the party branded Rightists. Shenggao was a studious man—skinny, bookish and unsuited to heavy labor. The camp he was sent to nearly killed him. He was saved through a chance encounter with a former employer who managed to get him relocated to a farm where the work was less severe.

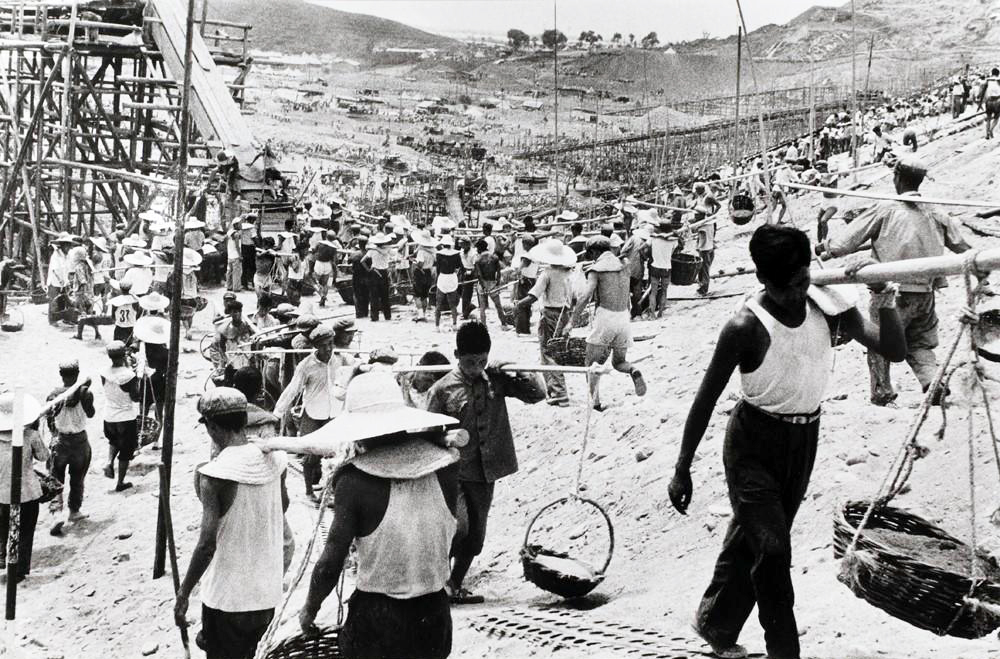

This purge coincided with the beginning of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, a massive and chaotic undertaking meant to wrench the country away from a primarily agrarian economy, collectivize land and rapidly industrialize China.

Land was not just redistributed among the peasants, but collectivized. Backyard smelters burned all night, tended by untrained or hastily trained peasants who had abandoned their fields to produce largely useless, low-quality steel. Local officials hid their dwindling grain reserves from higher ups for fear of retribution, and bad weather and mismanagement caused famine to sweep across the land, killing as many as 45 million people. It remains the deadliest famine in human history.

“My first name, if translated directly, is ‘jump,’ ” Xiong said. “Because that’s the year I was born.”

Yue Xiong was born on June 5, 1958. For Xiong’s family, it was an especially difficult time to welcome a child. Because Xiong was very young during this time, his chronology of events is a bit fuzzy; what he is sure of is that his father was imprisoned in labor camps for roughly half a decade, leaving his mother, Zhiyeng Peng, alone to care for their young son and with little income to do so. The family’s social standing made that task especially difficult.

While her husband toiled in labor camps, Zhiyeng Peng moved with Yue and her mother to Gao’an, less than two hours southwest of Nanchang by car today. There she was assigned an accounting job. The work allowed the family to get by, albeit poorly. The move was difficult for Xiong’s mother, who found herself friendless in an unfamiliar town; it felt like a tacit exile meted out by party officials. Still, she had been poor when she married Xiong’s father, so she was not branded an enemy of the people and was treated relatively normally. As a result, Xiong was allowed to attend a state-run preschool while his mother worked.

As Xiong approached school age, his father returned to the family but was still locked out from his forestry job in Nanchang. Instead, he moved the family to Nanhu, a rural, heavily wooded county where Xiong ultimately grew up. His father had requested the transfer because the farm he would be working on there was associated with what is now known as Jiangxi Agricultural University, giving him some contact with technical and engineering work, such as dam building, and a connection to the outside world.

“That actually was a pretty good environment, as far as my growing up and my education was concerned,” said Xiong. Others who had been caught up in the Anti-Rightist Campaign were sent much further afield, but Xiong’s father was able to return home regularly from the infrastructure projects he worked on. And every time he did he brought a book for Xiong. This gave Xiong unusual access to reading material, especially for a child from such a politically inexpedient family.

Reading taught him how to think, and thinking was dangerous.

“It was not a whole lot of books, but I really had the chance to read something outside the classroom,” said Xiong. “It’s difficult to determine specifically what kind of influence that early reading had on me, but that’s one thing I do remember pretty clearly. Very few kids had a chance like that.”

The books he was reading were government-approved children’s books—nothing remotely subversive, solidly revolutionary—but the voracious reading habit they inspired could be dangerous in and of itself. Reading taught him how to think, and thinking was dangerous if you weren’t willing to do it in line with the state. Any such threats were distant to young Xiong, who sparked an informal lending library among his friends.

“A lot of kids still remember those days, when they’d come to our house and read my books. It was always like that. Even later when I was [grown] up and I was able to get more books, people still could come to my house and read some books. I never got them back,” Xiong said, laughing. “My father [also] bought a radio. Boy, that was a big deal, because in the whole village no one had a radio.” The other children in Xiong’s village would gather around to listen with him.

Because of Xiong’s generosity, he and his father inadvertently educated a whole community of children—most who came from parents who had little to no education. “That’s one of the reasons the people in our village made friends with [my father] and respected him,” Xiong said.

Politics weren’t discussed in Xiong’s family. He believes his parents were trying to shield him and his two younger sisters from the knowledge that they had been deemed a “bad family.” Until the Cultural Revolution took hold in their village in 1967, he had no idea his family was any different from their neighbors. Despite educating him as best they could, his parents rarely spoke about his future.

“It’s because they didn’t know what expectation they could have [for me],” Xiong said. “Even though they were still trying to give me a normal life and encourage me, I don’t remember that we talked about what I wanted to be, what I could become when I grew up. I dreamed a lot of things I wanted to be when I was little. But that was out of reading those books, not really from my parents.”

Xiong had no plans to become a chemist as a child. He wanted to be a surgeon, a general in the army, or an astronaut exploring the cosmos. “That’s one thing I learned from my father, he liked that kind of stuff,” Xiong said. “We’d look at the sky, [and] he would tell me the names of individual stars and how to recognize them. That was pretty fascinating.”

Xiong’s family had a few years of relative peace in Nanhu before the Cultural Revolution began in 1966. Facing fallout from the disaster of the Great Leap Forward, Mao resigned as president, although he stayed on as the chairman of the Communist Party. A widening split between China and the Soviet Union affected him deeply, and Khrushchev’s fall from grace was a grim reminder that his own power was not unlimited.

The Cultural Revolution, like the Anti-Rightist Campaign of the late 1950s, was Mao’s attempt to weed out enemies and to further upend China’s prevailing social mores. The new administration’s work to haul the country out of the misery caused by the Great Leap Forward aroused the chairman’s suspicions. The new leadership was sidelining him, he believed, and, worse, was steering China down the same doomed path taken by the Soviet Union—away from Marxism–Leninism and toward a milquetoast form of socialism that aimed to coexist with the capitalist West.

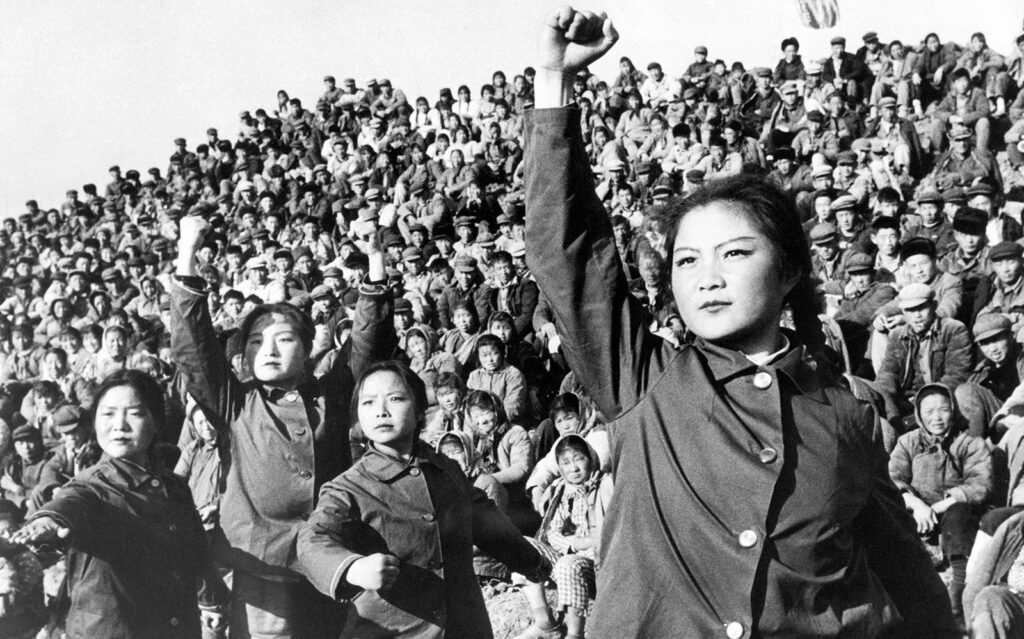

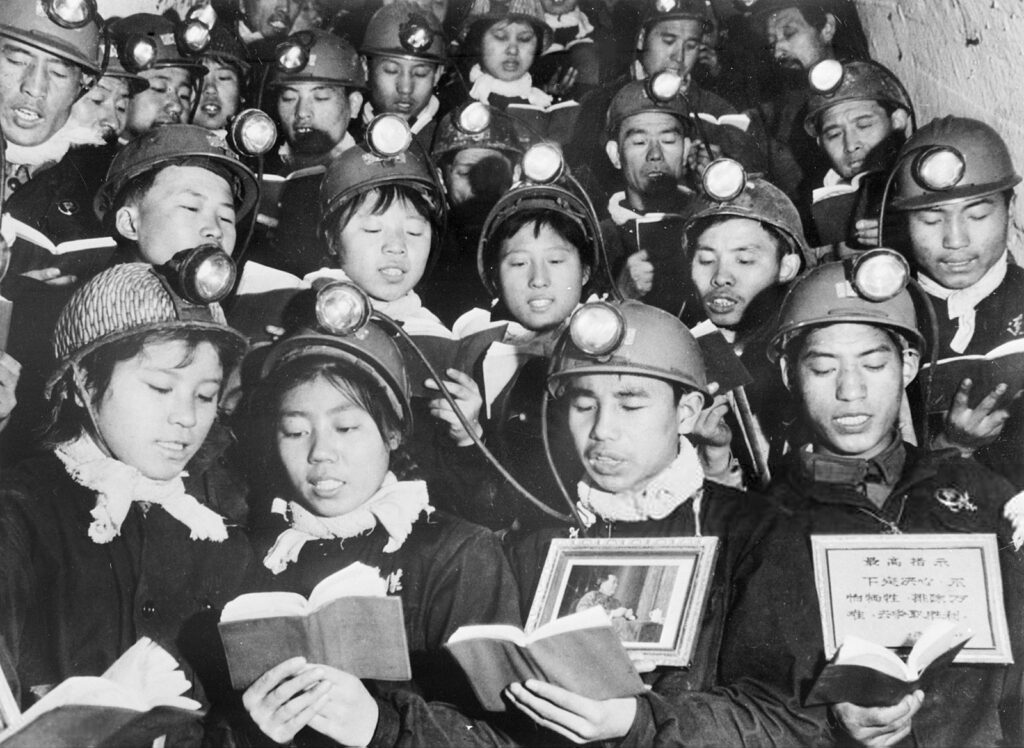

Sidelined or not, Mao still held immense sway. He called for a mass mobilization of the Chinese youth, who he believed would provide the necessary revolutionary fervor to withstand threats from the West and keep him in power. These young people were organized into paramilitary groups called Red Guards and given free rein to root out anti-revolutionary elements. High schools and universities were shut down; teachers were beaten and sometimes killed. Internal frictions within the Red Guards resulted in violent, rival splinter groups. The fighting over who was and was not a true believer in the personality cult of Mao paralyzed the country.

Xiong was nine years old and had entered middle school early when Red Guards began patrolling the countryside. His father, still a marked man, was again removed from the family. This time the punishment was even more severe. Shenggao Xiong was thrown into a labor camp where he was beaten frequently.

“I remember one night, after he came back from the camp, we slept on the same bed. And he held my hand to touch him. He came back with three broken ribs. He didn’t tell me what happened to him.”

Other abuses followed. Xiong’s parents were forced to kneel in front of an assembly weekly to self-criticize and confess to imagined crimes. His two younger sisters were sent to live with relatives, and he boarded at his middle school roughly 60 miles away from his home, where he was harassed by classmates. His mother was sent alone into a more rural village, where the Red Guards regularly searched her house.

“They found one textbook my father used when he was in college that was in Russian—my father studied Russian when he was in college,” Xiong said. “They said, ‘How can this guy study Russian?’ He must be a spy for the Soviet Union.” Just a few years earlier, a Russian textbook would have been completely acceptable, but after the Sino-Soviet split it could only worsen things for Xiong’s family.

One of the worst things that happened in the Cultural Revolution is not just the loss of technological development—they just turned the people against the people.

Separated from her husband and children, Xiong’s mother was at a loss and considered taking her own life, going so far one day as to write a suicide note. Unable to see her son, she called him at his middle school.

“I don’t remember the details, but I can remember vaguely that I sensed something was going to happen. I told her that no matter what happens, you’ve got to live. I was 10 or 11 years old,” said Xiong.

The chaos spilled into the 1970s. In an attempt to maintain order, Mao brought back Deng Xiaoping, who had been Mao’s preferred successor until he was exiled during the Cultural Revolution’s early years. Deng insisted on reopening high schools, hoping to forestall further social conflict and bring the country back under control. For two years, Xiong had access to real education.

“We were fascinated,” said Xiong. “The classroom teaching was different.”

These students had only three semesters of proper high school before a paranoid Mao exiled Deng again. Classes ceased or returned to rote repetition of Mao’s Little Red Book. Still, those three semesters of real school were enough to keep Xiong’s desire for education alive. Twenty-seven years later he ran into an old classmate who was working as a visiting scholar at Harvard, and she too credited much of her adult life to those three semesters of calm amid the chaos of the Cultural Revolution.

“We were so hungry and we didn’t realize it was so much fun to learn,” Xiong said. “It’s very much like when you don’t feel food is good, but after you’ve been starved for a couple days, you say, ‘Man, food is good.’ ”

Xiong graduated from high school in 1974 at the age of 16 and spent the next four years biding his time, alternately teaching and working on a farm. He drove buffalo and worked in an orchard growing peaches and pears. Every so often he would be called back to town to teach middle school. Colleges still weren’t open at the time, so it wasn’t unusual to have a high school graduate teaching middle school. Xiong was a good teacher, although his family background precluded him from assuming the position permanently.

“I just couldn’t get enough to read; I was really starved,” Xiong said. “At the time, [life] was getting back to normal and the stomach was not hungry anymore. We could feed ourselves. People had a relatively normal life, so to speak. I was just so hungry for learning. There was no opportunity, because the university was closed, the library was shut down, there were just no books, no one I could talk to.”

“You’re young, you still want to learn. You have this hunger for the knowledge.”

Xiong had a teacher from his old high school with a side job maintaining the shuttered local library. Through a careful system of friendship and bribery, he persuaded her to let him into the library with a bag. “I half borrowed, half stole,” he said. “I was reading anything I could grab.”

Xiong felt unmoored.

On July 28, 1976, a massive earthquake struck Tangshan, a city roughly 100 miles from Beijing. Within 23 seconds the quake killed an estimated 300,000 people and destroyed 90% of the city’s buildings. It remains one of the deadliest earthquakes ever recorded.

As the earthquake struck, Mao lay dying in Beijing. Within two months he was gone. Mao left behind a country that was deeply divided and confused. The political uncertainty was frightening at first—for a while it seemed like the country was on the verge of another revolution. Xiong’s father was convinced more chaos would follow, that he and his family would once again be caught in an opaque, political tug-of-war.

But as time passed, a sense of order was restored. A year after Mao’s death, in the summer of 1977, Xiong began to hear a rumor that universities would reopen. He took the National College Entrance Examination when it was made available at the end of the year; it was the first time the exam had been offered since the Cultural Revolution. Despite strong scores, the Rightist label that hung on his father still handcuffed Xiong. He was barred from university.

His dreams, which had seemed so close to being realized, were dashed. “I was so angry,” he said. “I just had my hopes lifted, and then it just vanished.”

Undeterred, Xiong wrote a letter explaining his situation to Deng Xiaoping, who had again taken control of the country after Mao’s death. Somewhat miraculously, Deng responded through a local contact, informing Xiong that the policy would be changed so that academic achievement, and not family background, would be the criterion for evaluating applicants.

Xiong went on to study biology at Fudan University, just as China was beginning to reopen to contact with the West. There was, slowly, greater interaction between scientists in the United States and China. Xiong began graduate studies at the Chinese Academy of Science in a lab under the direction of San-Chiun Shen, who had studied at Caltech and been involved in the “golden age” of molecular biology in the United States before returning to China in the early 1950s.

“He was almost prohibited from coming back, [but] he loves his country and he really wanted to do some science,” said Xiong. “He made some key contributions to the early molecular genetics in China, no matter how small an operation there was in the whole country. That’s [what] got me attracted in the first place.”

“You don’t know what to expect,” Xiong said, steeling himself for a Rambo-like entrance into the United States.

Few in Xiong’s cohort were thinking about molecular biology at the time. “I have to attribute some of that kind of thinking or conviction to the outside-of-classroom reading I’d been doing,” said Xiong.

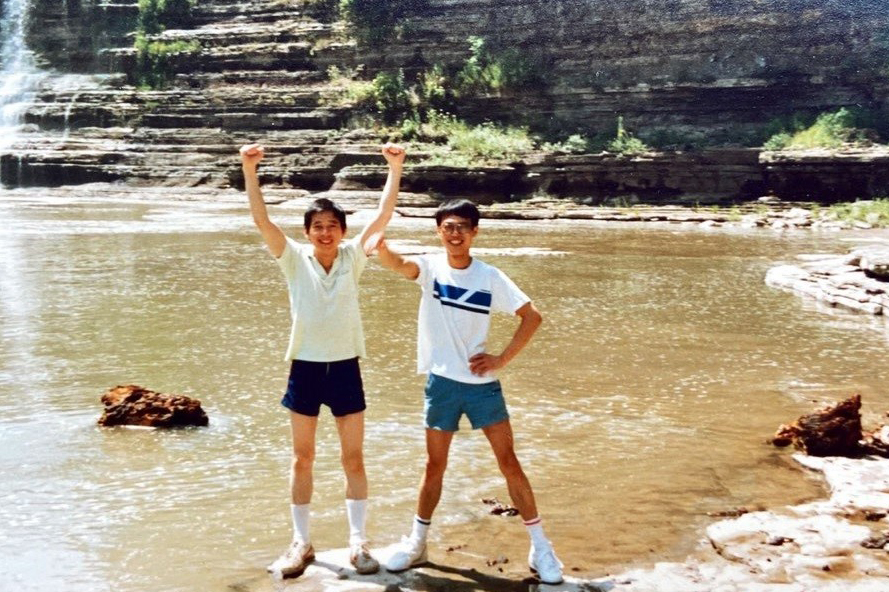

When given an opportunity to finish his doctorate in the United States through the China–United States Biochemistry Examination and Application (CUSBEA) program, Xiong leapt at the chance. CUSBEA was started by Ray Wu, a Chinese American professor at Cornell University. Wu created the program to assist Chinese students who, at the time, did not have access to entrance exams and other resources needed to pursue advanced scientific training at American universities. The first cohort of students began studying in the United States in 1982, and the program continued through 1989. More than 400 Chinese students were placed in graduate programs at more than 90 U.S. colleges through the CUSBEA program.

The United States, Xiong hoped, would bring opportunity—a break from the violence and upheaval that had so marked his early life in China.

The flight from Nanchang to New York took 30-some hours. After dinner the aircrew dimmed the cabin lights and put on a recent American blockbuster: the story of a traumatized U.S. veteran who returns from the Vietnam War only to endure continual harassment from the authorities—First Blood. It was the first American movie he’d ever seen. “You don’t know what to expect,” Xiong said, steeling himself for a Rambo-like entrance into the United States.

Despite this somewhat ominous introduction, Xiong loved the United States. His arrival in New York City was overwhelming, but he found the quiet upstate at the University of Rochester more comfortable. He bonded with others in his CUSBEA cohort, particularly a fellow student named Qing Yang.

Initially, he “couldn’t even find where the sodium chloride was on the shelf.” The language barrier was one obstacle, but the more pressing issue was his growing attraction to Qing Yang.

“We fell in love very hard,” said Xiong. “So I could hardly concentrate. My first rotation in the lab, I didn’t get anything done.”

But then Xiong forced his way into an advanced gene expression class, which, in turn, forced him to read academic papers in English and tackle rigorous coursework. By his second rotation, he and his soon-to-be wife “start[ed] calming down somewhat,” and Xiong began to excel. His department began to joke that he was a magician with pipettes.

Xiong went on to complete a postdoctoral year at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York and eventually became a prominent cancer researcher and joined the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he became the William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor in biochemistry and biophysics.

To hear Yue Xiong’s experiences in his own words and learn about his contributions to cancer and DNA research, visit the Science History Institute Digital Collections.

Xiong’s oral history is part of the Institute’s Oral Histories of Immigration and Innovation project, which makes freely accessible and searchable the oral histories of 70 immigrant scientists. This project is supported by a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.