Howard Berkey Bishop often told the story of how in the 1930s he began a campaign to rid the world of addictive substances. While driving his usual route from his home in Summit, New Jersey, to his fluorine plant in Easton, Pennsylvania, he spotted a hitchhiker on the side of the road. Bishop stopped and waved to the young man to get in the car. After a few minutes of small talk the hitchhiker realized he was in for more than a car ride.

“My friend,” Bishop said as he stared into the hitchhiker’s eyes, “which of the following habits would it be hardest for you to give up—liquor, tobacco, coffee, tea, cocoa, chocolate bars, or cola drinks?” “Tobacco,” the hitchhiker answered. Bishop started on his sermon, lecturing his passenger on the expense of smoking, that tar in cigarettes caused lung cancer, and that smoking made the body desire alcohol, which would then lead to hard drugs and the eventual loss of mental and physical health. At the end of the ride Bishop turned to the hitchhiker and invited him to hand over his pack of cigarettes and vow to quit smoking right then and there. The hitchhiker hesitated; Bishop asked him to open the glove compartment, which revealed many packs of cigarettes abandoned by other hitchhikers. Impressed, the young man agreed to quit and added his pack to Bishop’s collection.

In many ways Bishop’s training helped him formulate his response to the common pleasures of the day. After leaving the University of Michigan in 1902 the 24-year-old Bishop found a job as an analytical chemist at the General Chemical Company. Bishop understood his body as a carefully balanced chemical system. Adding caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol to this system upset the balance and made him feel sick and weak. By avoiding them he purified his body, leading, he hoped, to a longer and healthier life.

Bishop’s beliefs were likely influenced by the many movements that took health, both physical and moral, as their theme. The antialcohol Prohibition Party was founded in 1869, followed by the Woman’s Christian Temperance League in 1873. Meanwhile, the physical culture movement tried to address the consequences of an increasingly industrialized and sedentary society. And in 1906 Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, which enforced accurate labeling of medicines and food.

While working at the General Chemistry Company, Bishop cofounded a number of other businesses, including the Sterling Products Company in Easton. His career took off when in 1930 he developed a method for mass-producing hydrofluoric acid. At the time, the acid was used to refine oil and to make Freon gas for refrigerators. In the 1930s, as European nations rearmed, the demand for oil grew and the hydrofluoric acid industry boomed. Bishop sold off his part in Sterling in 1939, but instead of retiring to an indulgence-free life of leisure, he created the Human Engineering Foundation (HEF). He believed that people could “engineer” themselves to better health by changing their habits and decontaminating their bodies. Through his foundation he could now put his beliefs into action.

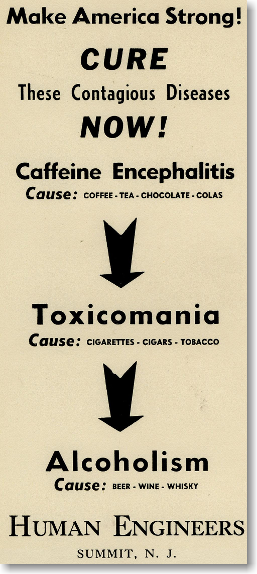

For Bishop even one bad habit was one too many and would lead to a cycle of dependency: Caffeine gives you too much of a buzz? Then drink alcohol and smoke to calm yourself down, and then drink more caffeine to increase alertness, and then indulge with more alcohol and tobacco to bring yourself back to where you started.

According to the HEF pamphlets Bishop distributed, this cycle disturbs the chemical balance of the human body, making users irritable, weak, and stupid. Cleansing these chemicals from the body would allow people to make the most of their innate physical and mental abilities. Bishop’s concept of balancing the body’s chemicals is in some ways similar to that of balancing chemical equations, an approach familiar to Bishop both from his student days and later as a chemical engineer.

The man who was convinced the world needed his help to banish nicotine, alcohol, caffeine, and the advertising industry that sustained them started out as a smoker and a coffee drinker. Bishop stopped smoking at age 14 and turned away from coffee at 26 (he only gave up on tea once he realized how much caffeine it contained). He never drank alcohol. After Bishop freed himself from stimulants, he claimed to have improved both his body and his personality.

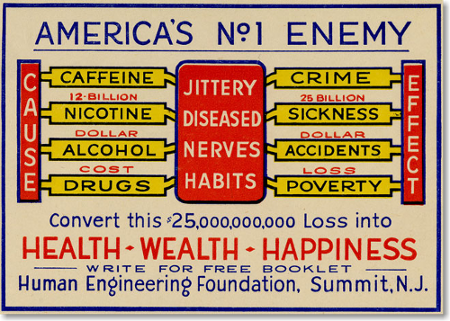

The HEF only employed a handful of people, but it distributed antidrug leaflets, business cards, and sent many, many letters between 1940 and 1961. The pleas in the leaflets ranged from asking Americans to abstain from caffeine to warning them that even a sip of alcohol could lead to an early death. After the war much of Bishop’s advice was connected with Cold War anxieties; underlying his honest desire for better health for everyone was a fear that the Western world would be unable to defend itself against the Soviet Union. If people could not resist addictive substances, how could they resist Communism without strong bodies and sound minds?

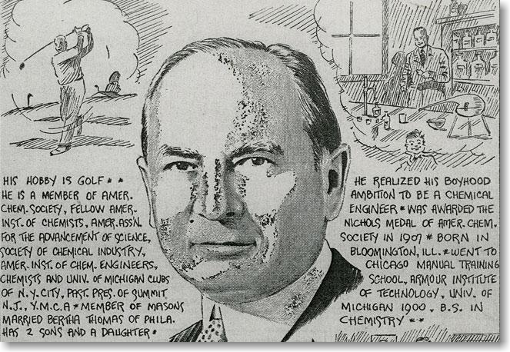

This portrait of Howard Bishop was found tucked inside a menu for a Sterling Products Company Christmas party in 1938. Bishop was president of Sterling at the time; so the party was likely in his honor. A fervent vegetarian and caffeine avoider, Bishop probably disapproved of the turkey and coffee on the menu.

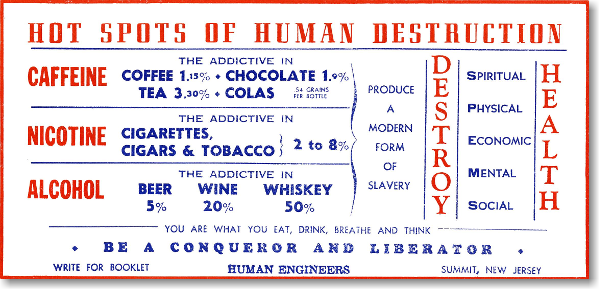

In this handout Bishop offers his theory of addiction. He implies that drugs cause the manifold ills of the world and notes their emotional and economic costs.

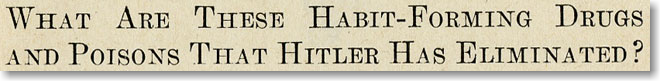

Although Bishop’s campaign would later focus on keeping America strong enough to withstand Communism, his paranoia over national security first became apparent when the United States entered World War II. In this pamphlet from 1941 he doubts that Americans could have a “will to win” as long as they were addicted to drugs. Not only do soldiers need strength, he argues, but so do civilians. Bishop cites Adolf Hitler’s then successes as affirmation of his convictions. Hitler had asked civilians and soldiers to give up tobacco and alcohol, and Bishop believed that their abstention allowed Germans to become faster and stronger, whether working in factories or piloting fighter planes. German doctors were the first to link smoking to lung cancer. Based on their work the Nazi government later launched an antitobacco campaign that banned smoking in many public places and limited cigarette advertisements, regulations Bishop hoped to realize in America. Bishop’s and Hitler’s politics were very different, but both tapped into wider discussions about the health of the individual and the health of the nation.

One of the tactics Bishop used in his attempts to persuade people to lead healthier lives was to equate addiction with slavery. In this leaflet he describes smoking tobacco and drinking coffee as physical acts of self-poisoning. Bishop’s language mirrors a common fear of the Cold War era: sleeper agents. As in Richard Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate, sleeper agents were individuals brainwashed and used as spies, unaware that their thoughts and actions were under the control of a foreign power. Bishop tried to wake up Americans to the brainwashing effects of tobacco and caffeine advertising, whose power he felt conditioned people to believe in the glamour of their products.

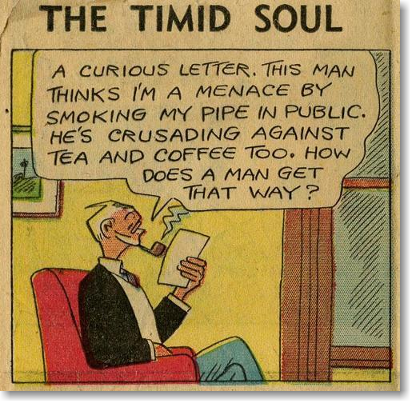

Bishop recognized that at least part of the success of tobacco and alcohol could be attributed to the endorsements, through advertising and everyday behavior, of famous people. He sent handwritten letters to celebrities and political figures whenever he saw them smoking or drinking in public, asking them to stop both for their personal health and to avoid influencing their followers. This policy also extended to characters in comic strips. In 1952 Bishop sent a letter to H. T. Webster, the artist of The Timid Soul. The strip’s humor derived from the wimpy personality of its main character, Caspar Milquetoast. Webster responded to Bishop’s letter by drawing a strip in which Milquetoast received the letter asking him to stop smoking a pipe. Instead of meekly giving in to the request Milquetoast resolved to purchase another 10 pounds of tobacco. Bishop’s crusade often met resistance but rarely was it so publicly ridiculed.

Bishop sincerely believed that avoiding addictive substances would transform humanity and open the door to a utopian future. He made his claim at a time when nuclear annihilation was a real possibility. Bishop argued that his way of life would increase the human life span by 10 years and so give people more time to improve society. Underlying all this was Bishop’s belief that the source of national antagonisms was the greed and hatred arising from the chemical effects of addictive substances on the brain. Bishop saw a clear connection between addiction and war; eliminate one and the other eliminates itself.

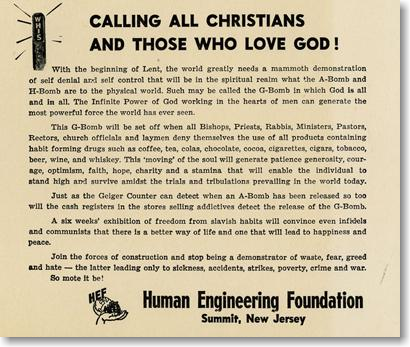

Bishop’s leaflets often targeted specific groups. Some were directed at golfers, others at housewives. This one is squarely aimed at the religious community. Bishop’s Christianity is evident in many of his leaflets; even those not targeted at Christians often contained quotes and moral lessons from the Bible. In this leaflet Bishop applies the concept of Lent (a time when Christians deny themselves luxuries) to his campaign against addictive substances. He also invokes the power and fear of the atomic bomb through the inclusion of the “G-Bomb” (the God bomb). Just as the A-bomb had the power to destroy, the G-Bomb had the power to help people give up tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine. Even “infidels and communists” would not be able to escape the blast radius of Bishop’s G-Bomb. In one leaflet Bishop brings together themes of religion, nuclear technology, and the politics of the Cold War.

Among Bishop’s many claims, his insistence that smoking causes cancer proved the most prescient. During the 1940s and 1950s, when Bishop wrote his pamphlets, few serious studies on smoking and cancer existed, and cigarette ads regularly appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Nonetheless, Bishop latched onto those few studies to support his prescription for a healthier lifestyle and constantly reminded his readers of the cancer connection. Not until a 1952 article in Reader’s Digest did public opinion begin to shift against tobacco companies, and only in 1953 did the American Medical Association ban tobacco ads in its publications. Bishop trumpeted this victory. In 1964, three years after Bishop’s death, the Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee on Smoking and Health released a report concluding that smokers were much more likely to develop lung cancer than nonsmokers.

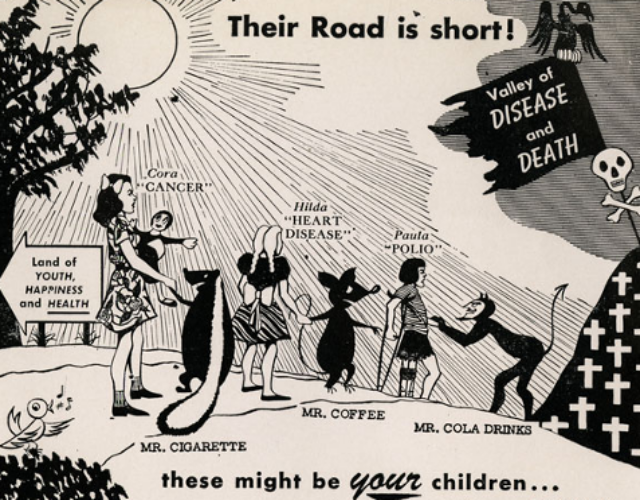

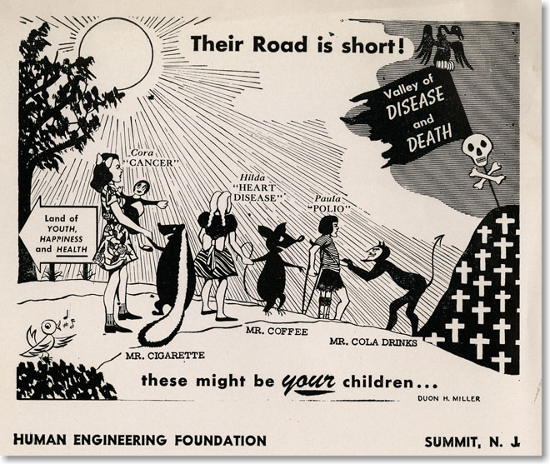

Not all of Bishop’s claims have proven as accurate; he unequivocally used any existing evidence to support his conclusions regardless of scientific merit. In this leaflet the cartoon asserts that coffee can cause heart disease (recent studies have suggested otherwise) and that soda can cause polio (likely a result of the 1951 book Diet Prevents Polio, in which Benjamin Sandler erroneously claimed that sugar increases the risk of polio). Many of Bishop’s messages were useful; many others were misleading.

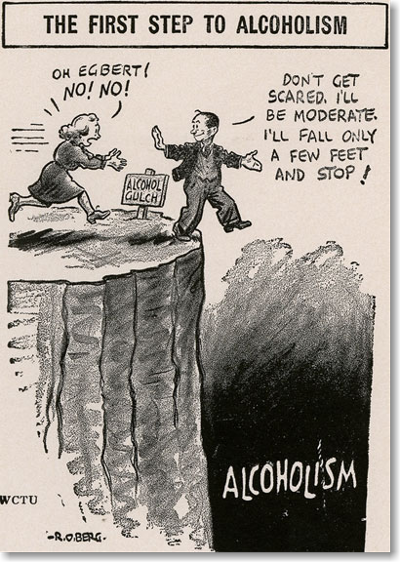

Although this leaflet begins by exaggerating the risks of drinking even small amounts of alcohol, it morphs into a treatise on social and human evolution. Bishop grew up at a time when physical fitness as an ideal had spread from Europe to the United States. This concept may have influenced his belief that the human body had originally evolved for survival in the wilderness and still retained its instincts to eat meat (and caffeine). At a time when most jobs involved manual labor, people still required meat to maintain their bodies. But in this leaflet Bishop argues that humankind has entered a new era, one in which most people do not have physically demanding jobs and in which the instinct to consume meat and caffeine is an anachronism. Meat eating causes obesity, which leads to nervousness and depression, which leads to alcohol abuse as a way of drowning these psychological troubles. And so Bishop advocated vegetarianism to prevent alcoholism.

Bishop’s campaign against drugs and alcohol centered on the idea of purifying the human body; so perhaps it is surprising that his abhorrence of addictive substances did not extend to medicine and other compounds. After fluoride was first introduced into a public water supply in 1945, Bishop defended fluoridation against criticism. He had worked with fluorine compounds, first while developing laundry detergent and later while working with hydrofluoric acid. He endorsed fluoride’s anticavity properties, adding that he used it in much larger doses than found in fluoridated water. This leaflet represents one of the rare instances where Bishop advocated adding chemicals to rather than subtracting them from the human body.

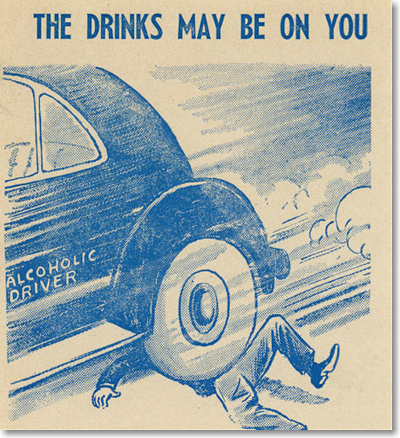

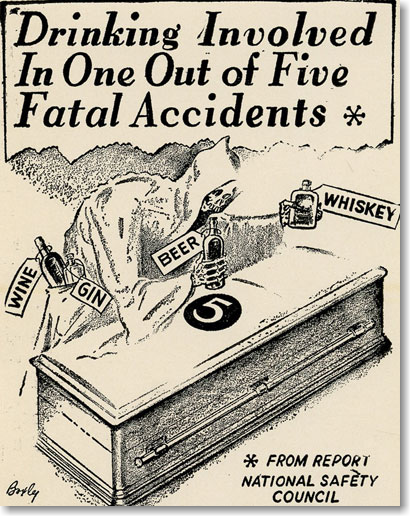

Bishop often embellished facts to make his arguments more compelling. In this leaflet a drunk driver crushes a person while various shocking statistics are listed below: 38,000 traffic-related deaths in 1952, with more than 100 traffic-related deaths each day. Although Bishop does not specifically say so, his words strongly imply that all these deaths were caused by drunk drivers.

Bishop liked comparing himself to historical figures, both to inflate his own importance and to evoke feelings of patriotism. In this leaflet he portrays himself as a modern Paul Revere, not just warning Americans about the dangers of addictive substances but also tying the fight against them to the military and political future of the country. During the Cold War many proxy battles were fought against Communism. Bishop applies the language of political freedom to the liberation from addiction; he considers both moral imperatives. Religious, political, and historical influences converge in this leaflet, which is representative of Bishop’s entire campaign.

This cartoon shows a booze-toting Death looming over victim number 5, representing the one death out of every five that results from drunk driving. It echoes present-day ad campaigns against drunk driving, complete with catchy slogan: “If you drive don’t drink. If you drink don’t drive.” Bishop wrote these leaflets during the 1950s and early 1960s, when Prohibition was almost 30 years past. Here he targets a specific abuse of alcohol, instead of condemning all drinking, suggesting an evolution from earlier beliefs in which any drinking was unjustifiable.

Howard Bishop’s crusade to make America morally and physically healthy is noteworthy if only in its odd optimism. Bishop slathered his pamphlets with gratuitous images of death and destruction because he didn’t care if people responded out of fear or out of understanding, as long as it led them to improve their lives and ensured the safety of their country. He genuinely seems to have believed (almost naively) that if everyone adopted his lifestyle, they would be ushered into a new era of peace and happiness. It’s impressive that he maintained this attitude through multiple wars, the development of the atom bomb, and the invention of countless addictive drugs. Only years after Bishop’s death did the general public accept the connection between smoking and lung cancer, a connection he tried desperately to publicize. The story of the Human Engineering Foundation, an organization run by Bishop until the day he died, tells how one man devoted himself to what he saw as the public good at a time when threats to the individual and to society appeared overwhelming.

The images in this article were taken from the Science History Institute’s archives.