Michael Phelps marched into the Beijing National Aquatics Center with his three teammates. The camera lingered on his anxious mother while the crowd hummed with anticipation. If the American team won this race, the 100-meter medley relay, Phelps would earn his eighth gold medal of the 2008 Olympics and eclipse Mark Spitz, who had won seven golds in 1972.

Phelps would swim the butterfly stroke in the third leg. As he waited, he removed his cocoon of hooded robe and headphones, revealing a sleek black swimsuit that looked more like a pair of tights than a bathing suit. Aaron Peirsol, who was swimming the first leg, lowered himself into the pool and hung on the edge.

The buzzer sounded. Peirsol dove backward and flew across the pool in a foamy jet of water. He was a hair’s breadth ahead of his Australian rival when he tagged in Brendan Hansen, who lost the lead to Japan by the time he handed off to Phelps.

Within seconds of diving in, Phelps was neck and neck with the Japanese swimmer, leaping and plunging on every stroke like a possessed dolphin. On his turn Phelps ricocheted off the wall and gained a substantial lead on both the Japanese and Australian competitors before his teammate Jason Lezak took over for the final sprint. Thanks in part to the buffer provided by Phelps, Lezak finished the race in first, with the team clocking in at just over 3 minutes and 29 seconds, simultaneously demolishing a world record and giving Phelps his eighth gold medal.

In all, U.S. swimmers walked away with 31 medals, but the Bejing games did more than prove American dominance in the sport. It also cemented the dominance of swimwear maker Speedo’s iconic new swimsuit, which, according to the company, was worn by 98% of swimmers who medaled at that year’s games.

As record after record fell in the Olympic trials leading up to Beijing and then in the games themselves, it became clear that athletes wearing Speedo’s new line of swimsuits had an edge. But Speedo’s success would force the competitive swimming world to reckon with difficult questions: Should swimmers adopt equipment not everyone can afford? How long is a world record supposed to stand? And perhaps the trickiest question, can technology make people too good at a sport?

Swimsuits at the turn of the 20th century were designed more for modesty than speed. The bulky woolen trunks and shirts swimmers wore became sodden quickly and had far more drag than the skin they covered. But wearing anything tighter or skimpier was out of the question in those socially conservative times, as Australian swimsuit maker Alexander MacRae found out when he released the Racerback in 1927.

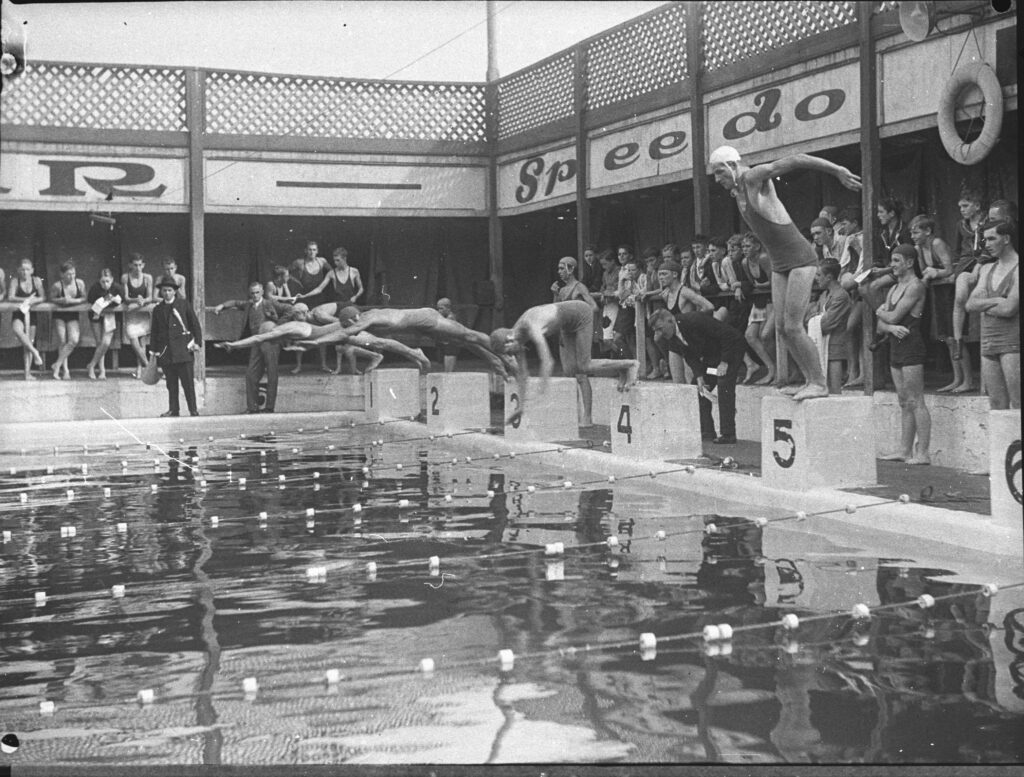

Start of a relay race at a suburban Sydney pool, 1935. Competitors are wearing Speedo’s game-changing Racerback swimsuit.

Banned from many beaches for being too revealing, MacRae’s form-fitting suit was designed for competition. The Racerback left the shoulders and back exposed for better freedom of movement and eschewed waterlogged wool for silk fabric that was more hydrodynamic. In 1928 MacRae established the Speedo brand, and the company’s suits were adopted by competitive swimmers around the world. Clare Dennis broke the Olympic record in the 200-meter breaststroke while wearing a Speedo at the 1932 Olympics, but her bare shoulder blades nearly got her disqualified. Topless swimsuits for men made their first Olympics appearance in Berlin in 1936, but anyone trying the same look in Atlantic City could expect a fine.

In the decades that followed, synthetic fabrics helped suits become tighter, lighter, and smaller; and as before, offense and outrage followed. It was a suit made of natural fabrics, though, that scandalized swim fans at the 1972 Olympics in Munich. The East German women’s performance at the games was unremarkable, but the gossamer cotton “skinsuits” they wore turned nearly transparent when wet.

“These suits are gross,” Speedo’s North American manager, Bill Lee, later told Sports Illustrated. “You can see everything.”

The swimming world took notice of East Germans in a different way after the 1973 World Aquatics Championships in Belgrade. Wearing a slightly less-revealing Lycra version of the skinsuit, the East German team drubbed the competition, winning 10 of the 14 races and setting seven world records.

As swimsuits changed, controversy followed, at both the pool and the beach. Clare Dennis [standing second from the right] won gold at the 1932 Olympics but was nearly booted from the competition for showing too much shoulder.

American fans were no longer unnerved by the suits’ bare-it-all nature but by something that seemed more insidious. Many were convinced the East Germans’ results had more to do with their suits than their abilities. As the mother of one American swimmer remarked, they just couldn’t have been that much better trained.

American swimmers soon tried to level the playing field by switching out their nylon Speedos for Belgrads, as the suits came to be called. As American racing times improved, attitudes toward the suit changed.

“I feel the suits are not indecent as long as everybody wears them,” American swimmer Shirley Babashoff told Sports Illustrated not long after setting an American record in the 500-yard freestyle. “This may be more psychological than physical,” added Heather Greenwood, “[but] I always think I’m going to win when I wear it.”

And despite Lee’s disgust, his company was busy making its own version of the skimpy suit. “We began making our own skinsuits 30 seconds after the Belgrade meet,” he confessed. He went on to speculate that Lycra skinsuits were just the beginning: in the future swimmers might be sprayed with rubberized coating before meets. Lee was almost right.

Human skin is not very efficient at moving through water, especially when compared with the hides of aquatic creatures. Sharks, for instance, reduce drag with tiny, toothlike structures (called denticles) that cover their bodies and create low-pressure zones. These swirls of water subtly pull sharks forward. Taking inspiration from sharkskin, in 2000 Speedo developed the Fastskin, a suit patterned with V-shaped ridges designed to act like denticles.

When swimmers wearing Fastskins took to the starting blocks at that year’s Sydney Olympics, they looked dramatically different than the skimpily clad Olympic swimmers from just four years before. One version of the new Speedo suit stretched along the body from wrist to ankle. The more skin covered, Speedo’s logic went, the faster a swimmer would be.

And the suit did seem to make swimmers faster: more than 80% of swimmers who medaled at the Sydney Olympics wore a Fastskin, and 13 of the 15 swimming records broken at the games were made by swimmers wearing some version of the suit. (Although Speedo made their suit available to all Olympic swimmers before the games, only Speedo-sponsored athletes were gifted custom suits fitted to their bodies.)

For the 2004 Athens Olympics, Speedo released the Fastskin FSII, which claimed to reduce drag even further and was embraced by many of the world’s top swimmers. Like the original Fastskin, the suits worn in Athens were made of spandex coated with Teflon, which helped the suit shed water. But the woven nature of the material couldn’t prevent water molecules from bouncing erratically off the texture of the suit’s weave, which stubbornly created drag. Leading up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Speedo began toying with a whole new way of making swimsuits, an approach that would make the Fastskin look slow.

Just putting on the suit was an ordeal that could take upward of 20 minutes.

After a few years of experimentation Speedo discovered that coating swimsuits with polyurethane created an exceptionally hydrodynamic surface. But to figure out how to make the most of the material, Speedo reached out to an organization known for cutting-edge suits of a different kind: NASA.

Speedo knew that NASA was already studying the science of racing: the same wind tunnels used to test the aerodynamics of spacecraft also helped Formula One and NASCAR engineers design faster cars. When Speedo contacted NASA, the space agency agreed to share its testing facilities at Langley Research Center. Stuart Isaac, at the time Speedo’s senior vice president of sales and marketing, claimed that the partnership raised eyebrows among both scientists and other sports-apparel companies.

“People would look at us and say, ‘This isn’t rocket science.’ And we began to think, ‘Well, actually, maybe it is.’ ” Rocket science or not, Speedo’s next-generation suit was technologically sophisticated. To avoid drag-making seams the new suits were put together using a technique called sonic welding, which joined the different sections as if they were pieces of metal.

Over the next year Speedo added polyurethane panels to its existing design, replacing the Teflon coating used in previous models. It soon became clear that the more polyurethane suits had, the more rigid the suits became and the less drag they created. There was only one problem: as the concentration of polyurethane increased, the suits became more fragile and tore more easily. For that reason Speedo stopped short of building a suit made entirely out of a sheet of pure polyurethane. For an extra boost, engineers etched the polyurethane with the shark skin-inspired texture of the Fastskin.

U.S. swimmer Michael Phelps adjusts his swimsuit, the controversial Speedo LZR Racer, at the 2009 FINA Swimming World Championships in Rome.

Speedo dubbed the new suit the LZR Racer, and the end result was a jet-black swimsuit that reached from the shoulders to the calves and hugged the skin like a vise grip, a skinsuit on steroids. The LZR (pronounced “laser”) compressed its wearers’ bodies into seamless, hydrodynamic tubes. That extreme compression came with an annoying disadvantage, though: just putting on the suit was an ordeal that could take upward of 20 minutes. Some swimmers resorted to putting plastic bags on their feet to reduce the friction as they stuffed themselves inside.

Sara Dickerman, a reporter for Slate who tried out the suit in February 2008, remarked that putting it on made her feel “like a lobster trying to molt backward.” The version that Dickerman wore looked like a drab Jazzercise outfit with tank-top straps that extended into capri leggings. Once Dickerman managed to squeeze in, she said it felt “like paper, not cloth,” which revealed another problem with the suit: after a few races it would tear or stretch beyond usefulness. Since an individual suit cost anywhere between $200 and $500, it was too expensive to be disposable for unsponsored swimmers. But soon these suits would become mandatory for world-class swimmers who wanted to win.

Before the 2008 Olympics in Beijing there were rumblings within the swimming community that the suit would topple records, and Speedo was calling it the fastest swimsuit ever made. Evidence of that was on display at the U.S. qualifying trials leading up to the Olympics, where 66% of competitors wore the suit. Many who qualified attributed their success to the LZR, and heading into Beijing at least 76% of competitors were bringing along a LZR, many of them defying their sponsors to do so. Eventually those sponsors, including Nike and Adidas, begrudgingly let their athletes wear Speedo’s suit. In all, 25 world swimming records were broken in Beijing, more than in any previous Olympics.

But the suit wasn’t just successful because it turned the wearer into a human torpedo; early adopters soon discovered what made the suit so fast.

The constant setting and smashing of world records threatened to make such records meaningless.

When swimmers dove underwater, instead of sinking to the bottom, they found themselves floating back up to the surface. Why? Tiny air pockets were getting trapped between their skin and the fabric of their suits. These air pockets allowed swimmers to float as if they were wearing a very thin life jacket. Because friction from water is so much greater than friction from air, even a small increase in a swimmer’s surface area above water makes a huge difference in top-tier races.

As for the sharkskin patterns Speedo had marketed for a decade? They did nothing for swimmers.

In 2012 George Lauder, a professor of ichthyology at Harvard University, published a paper that showed artificial sharkskin had no effect on drag. Using a large tank of recirculating water, Lauder compared the drag of real sharkskin with that of the Fastskin FSII. Lasers lit up reflective particles in the water while a high-speed camera tracked how the particles moved over the different types of surface. He concluded that the denticle-like textures don’t work on humans the way the genuine items work on sharks—in part because sharks bend their flexible, cartilage-filled bodies back and forth to swim, which no human swimmer can do. (Undiscouraged, Speedo still advertises the biomimetic properties of its sharkskin swimsuits on its website.)

After the Beijing games Speedo’s competitors scrambled to reverse-engineer the suit.

Swimwear maker Arena was first to respond with the X-Glide, a similar type of polyurethane full-body suit; more companies followed its lead. Within a matter of months the LZR was obsolete, outclassed by new suits that were made almost entirely of pure polyurethane (not a mixture like Speedo used), making them fully impermeable and allowing them to shed water like the oily feathers of a duck.

The effects of this sportswear arms race were undeniable. In 2009 the world records set at the Beijing Olympics were blown to smithereens at the World Swimming Championships. Nearly every competitor wore some variation of a full-body polyurethane suit.

Leaders of the International Swimming Federation, or FINA, realized they had a problem. The constant setting and smashing of world records threatened to make such records meaningless, and expectations were being established that could not be met.

Anger spread among both swimmers and spectators, who recoiled at the idea of “technological doping.” The suits seemed to embody a competitive imbalance in a sport already dominated by athletes from wealthy countries. Those who could not afford the new swimsuits were starting every race at a huge disadvantage. Even Phelps, who rode his polyurethane suit to victory in Beijing a year earlier, threatened to boycott any event where they were allowed after he lost to Germany’s Paul Biedermann at the 2009 World Championships. (Perhaps coincidentally, Phelps’s sponsorship by Speedo meant he wore the outdated LZR while many of his competitors, including Biedermann, had access to more advanced swimsuits.)

At the end of 2009 FINA made a decision: all full-body polyurethane suits would be banned from international competitions. Governing bodies in most countries followed FINA’s lead, including USA Swimming. Only swimsuits made out of permeable textiles that could not capture air bubbles would be legal. Men’s suits could not extend above the waist or below the knee, and women’s suits could not go past the shoulders or below the knee.

The ban was nominally made in the interest of equal access to equipment, but it was also a clear attempt to maintain the sense of gradual progression in the sport. Competitive swimmers are not only racing the other swimmers in the pool; they are racing every swimmer who has previously set a world record. Before the LZR Racer, records were being broken roughly every four years. After the LZR Racer, records were being broken first in preliminary heats and then again in the finals of the same event. The ban turned back the clock to before 2008, but the damage had already been done to the record books. Eight years on, swimmers at the Rio Olympics were only just starting to catch up to the times set in Beijing.

Although polyurethane has been banned, Speedo and its competitors are still working within the confines of the rules to eke out every advantage they can. The focus has shifted to elastic suits that help conserve energy by compressing leg muscles and preventing unnecessary movement. Even Phelps has his own line of suits touting Exo-Core technology that combines two layers of stretchy fabric with questionable marketing embellishments. But most athletes are no longer overly concerned with what swimsuit they wear, and even coaches admit that some of these impressively named designs only provide a placebo effect.

It’s worth noting that swimsuits aren’t the only example of technological “doping” in the swimming world. Olympic pools, for instance, are now built to reduce the pushback from waves created by swimmers displacing water. Lane dividers divert the waves down and under athletes where they slosh harmlessly into the empty buffer lanes on either side of the pool.

So if swimming times are being doctored through pool design and other technologies, should polyurethane supersuits have been banned in the first place? Back in 2009 most swimmers and coaches certainly thought so; predictably, swimsuit companies did not. One could argue that FINA overreacted to a temporary bubble in swimming records by enacting regulations that, history intimates, will be circumvented someday. It’s only a matter of time before a new field of research (perhaps nanotechnology) is applied to swimsuits, leading to drastically improved performances without breaking the current rules. Those same rules are vague and open to interpretation; can anyone precisely pin down what counts as a “textile”?

As for the original justification for the ban—accessibility and competitive balance—the swimming community just stopped talking about it. It’s a sad reality that talented swimmers are more likely to succeed in wealthy countries that can afford to scout athletes from a young age and invest in the equipment and resources necessary to train them. The swimmer with the most potential in the world right now might be living in a country with none of those resources.

Usually that inequality is invisible once athletes reach the swimming pool on race day. Whatever edge in training and coaching a swimmer has is not readily apparent to spectators. Most of us see men and women with unique abilities competing within a set of rules that fairly determines the best of the best.

Polyurethane suits upset that understanding. Fans saw physical proof of performance being skewed—not by luck or skill, but by invention. The focus of competitive swimming shifted away from the individual to the equipment. We had fun speculating that Phelps’s unusually long arms and relatively short legs gave him a physical advantage when swimming, but we had less fun speculating that Biedermann won because he was wearing the newest swimsuit. Had swimming become another NASCAR with its Chevy–Ford rivalry, a proxy war between manufacturers?

The one thing that hasn’t changed since the Olympics were first held in ancient Greece is human skin. If FINA really wants to maintain the integrity of the sport, perhaps they should have swimmers compete the same way the Greeks once did: in the nude.