Did you see Universal’s hit movie about birth control and abortion? No? Well, maybe that’s not surprising since it was released in 1916. While the silent movie, titled Where Are My Children? is more than a century old, its central question—who “deserves” access to reproductive rights—still resonates today.

Pioneering director Lois Weber may not be as well known to modern audiences as Cecil B. DeMille, Charlie Chaplin, or even D. W. Griffith, but during the 1910s she was one of the highest-paid and most sought-after movie directors. She wrote and directed films on social issues of the day, such as economic inequality, women’s rights, capital punishment, and drug addiction. Weber first tackled the issue of birth control and abortion in the 1916 silent film Where Are My Children? and returned to the topic in 1917 with The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, based on the legal problems pioneering birth-control activist Margaret Sanger encountered.

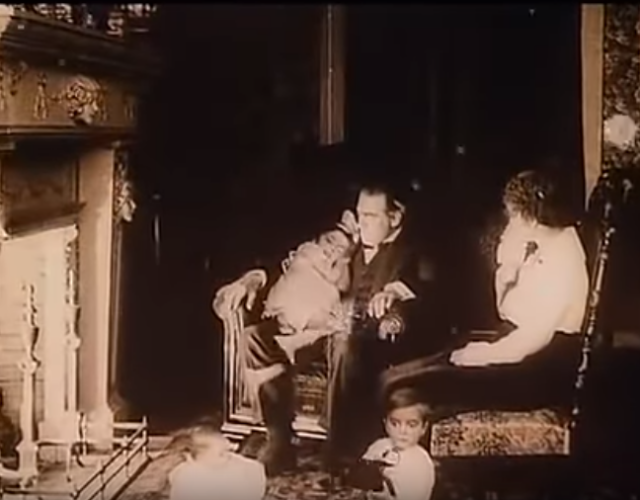

Where Are My Children? follows Mr. and Mrs. Walton, a district attorney and his wife, who live a comfortable but childless life together. Mr. Walton longs for children, while his wife prefers to remain child-free in order to live the life of a social butterfly. Over the course of the film Mr. Walton prosecutes two different doctors, one for distributing information on “birth regulation” and the other for performing abortions. At the end of the second trial a book of patients is revealed in which the district attorney finds the name of his wife and all her childless friends. He storms home to confront her, and their once-happy marriage grows sour. The film ends with the two of them aging by the fire, haunted by three ghostly children who never were and the question from the final intertitle, “Where are my children?”

Weber believed her work could be social commentary, teaching the audience a lesson and provoking discussion after they left the theater. In Where Are My Children? she uses storytelling and various film techniques to present the issues at hand, including the difference between birth control and abortion, who uses contraception, and who should have children. The two physician characters—Dr. Homer, the birth-control advocate, and Dr. Malfit, the abortion provider who caused the death of a young woman in his care—serve as one-dimensional human representations of these issues. Viewers see the product of the actions, trials, and convictions of the two men.

Weber used plot devices, close-ups, and crosscutting to generate sympathy for Dr. Homer and birth control and to demonize Dr. Malfit and abortion. Even though both doctors are found guilty, Weber makes the audience question whether distributing information on birth control should be considered “obscene” and therefore illegal. (Providing information about contraception was an illegal act under both state and federal obscenity laws.) At the same time, she reinforced the idea that abortion is murder and should remain outlawed.

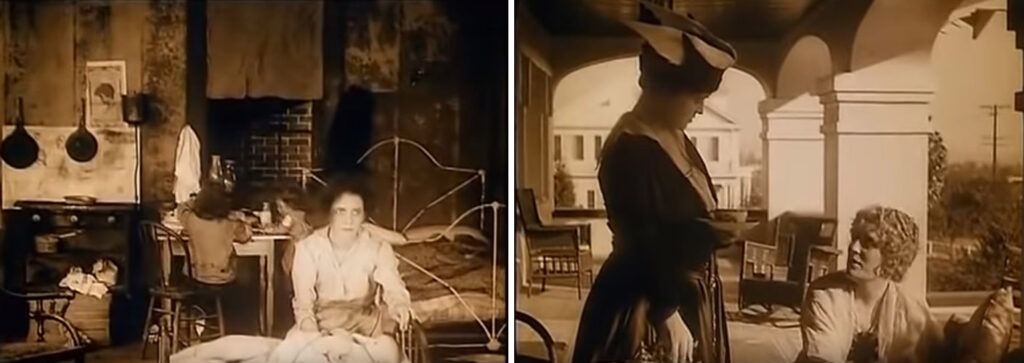

Her visual techniques create audience sympathy for the nameless women living in poverty seen by Dr. Homer and disapproval of the society women, including Mrs. Walton, who visit Dr. Malfit. During the trial Weber crosscut between scenes of working-class women unable to care for their children or being abused by their husbands and a friend of Mrs. Walton who chooses to have an abortion so she can keep attending parties. As both writer and director, Weber composed these scenes to provoke audiences into supporting birth control to limit the number of children produced by poor women while chastising rich women for avoiding motherhood in favor of social engagements.

Weber crosscut between the stories of a poor woman caring for her children and wealthy women discussing how to end an unwanted pregnancy.

The film’s female characters reflect the reality of that time: women shared information about birth control and abortion among friends and family in order to avoid having children. While some real-life activists spoke openly about birth control, many women discussed the issue only with trusted companions because the obscenity laws prohibited such topics. Constrained by government censorship, American women relied on word-of-mouth recommendations and advice to learn about birth control and abortion.

Weber’s movie, however, does not fully represent the lives of women who sought contraception—or of those who did not. The women who do not use birth control in the movie are portrayed as too ignorant to realize they could prevent pregnancy, while the women who have money remain childless through abortion. In reality, women of all classes sought ways to prevent or end pregnancies. Wealthy women were often able to procure newer, mass-produced methods of birth control, such as rubber condoms and diaphragms, or receive abortions from discreet doctors. Many poor and working-class women did not have the resources to buy these illegally imported contraceptive devices or to visit a physician. Instead, they relied on older forms of contraceptives (such as wads of wool) and abortifacients (such as pennyroyal), or abortions performed outside a doctor’s office, including self-induced abortions.

To a modern audience a movie that is pro–birth control but antiabortion, and advocates for certain women to have children while others should not, seems odd, if not outright offensive. However, Lois Weber created Where Are My Children? within a eugenics framework, and when viewed from that perspective, the film makes more sense. Eugenics is based on the unscientific, racist, and discredited idea that all traits are inherited and that the human species could be improved only through breeding.

The concept of eugenics gained popularity in the United States during the 1910s. And while many different approaches to eugenics existed, they were all based on the idea that people with “better” traits should have more children, while “inferior” people, including those who lived in poverty, should have fewer children. Weber used this perspective in her movie, and so her argument for birth control for poor women and motherhood for rich women is not a contradiction but rather an assertion of eugenic principles.

When the movie was originally released, some reviewers felt that including both birth-control and abortion plots muddled the film’s message. One reviewer wrote that the plot started clearly, but then “the idea becomes so hazy that it is hard to grasp the true meaning.” This mixed message is embodied in the character of Lillian, daughter of the Waltons’ housekeeper, who is seduced by Mrs. Walton’s brother and pressured into an abortion that kills her. It is her death that causes Mr. Walton to investigate Dr. Malfit and leads to the dramatic reveal of his wife’s actions. Weber never directly addresses the issues of premarital sex or birth control for unmarried women, so the audience does not know if Lillian’s death is a punishment for her having sex before marriage, if her life would have been spared if she used birth control, or if her death was just a convenient plot point to launch the final act of the film.

The film may have lacked a clear message, but it struck a nerve with audiences. Although at first the National Board of Review and numerous local film boards refused to screen the film, Where Are My Children? eventually made its way to theaters and was a box-office hit. It demonstrated that Hollywood was capable of addressing complex and controversial topics and led to other films on the same issue. Real-world discussions about contraception, abortion, voluntary motherhood, and eugenics were reflected on the big screen in a way they had not been before. Lois Weber and her film paved the way for American cinema to openly discuss birth control at a time when disseminating information about birth control was a crime. Despite its eugenics message, the film reminds us that the battle over reproductive rights has a long history.