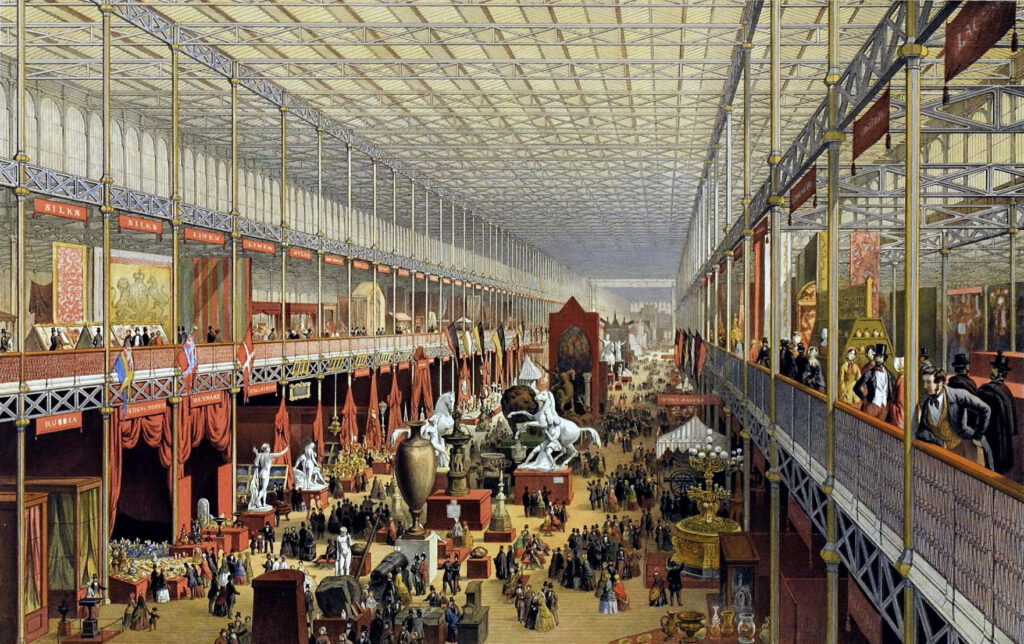

The Crystal Palace in London astounded the globe when it opened in 1851, as part of a world’s fair. The exhibits inside included every modern wonder: looms and rifles and gigantic telescopes; diamonds the size of fists and Māori carvings from New Zealand; even an early fax machine and a barometer powered by leeches—among so much else.

Perhaps the most astonishing thing was the palace itself. The building rose 128 feet tall and covered an area three times the size of St. Paul’s Cathedral. More incredible still, all the walls and ceilings were made of glass, a frightfully expensive material then. People felt like they were walking around inside crystal dinnerware. Over the course of the fair’s six-month run, six million people paid a shilling or more to wander around and gape.

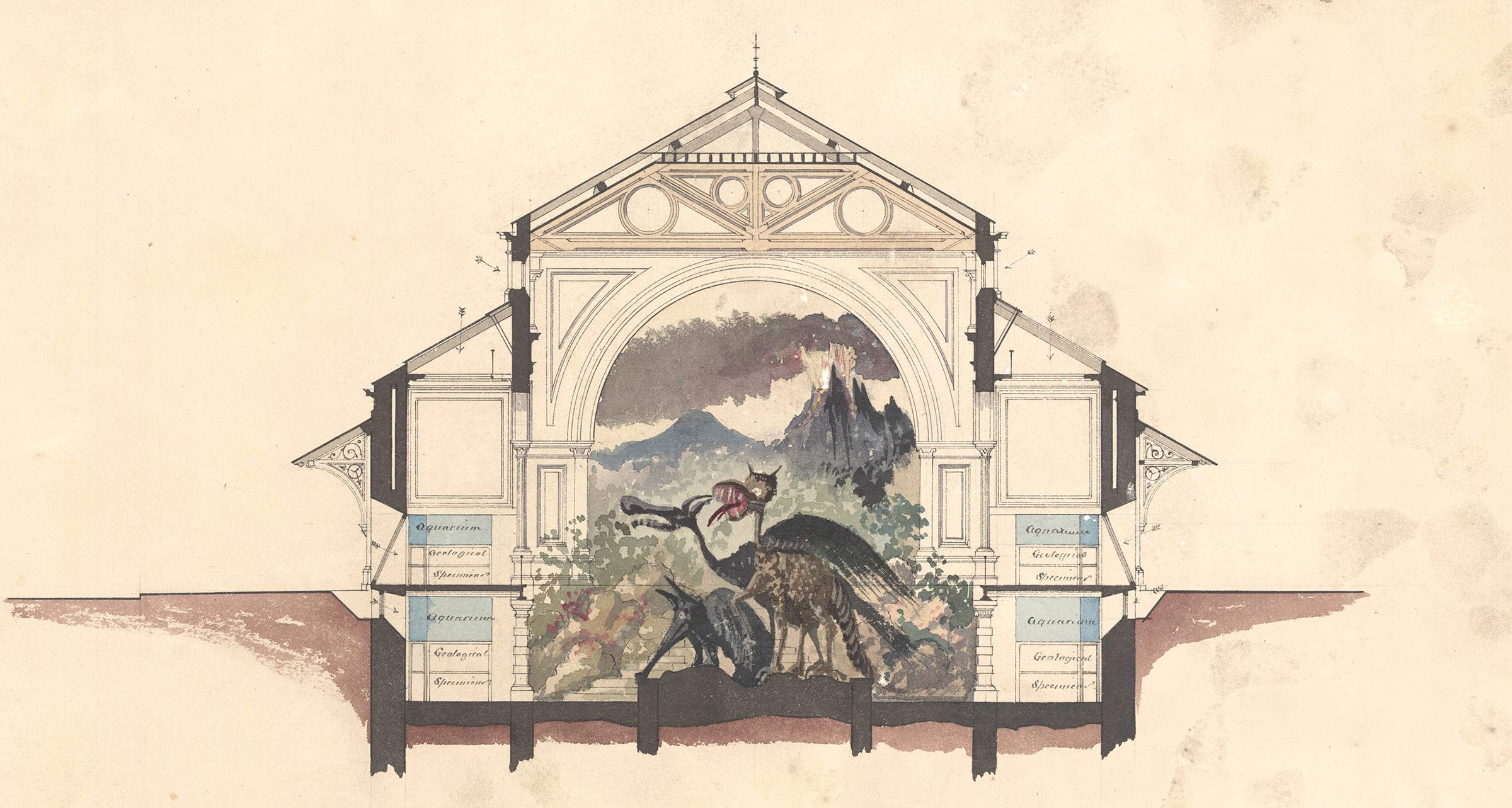

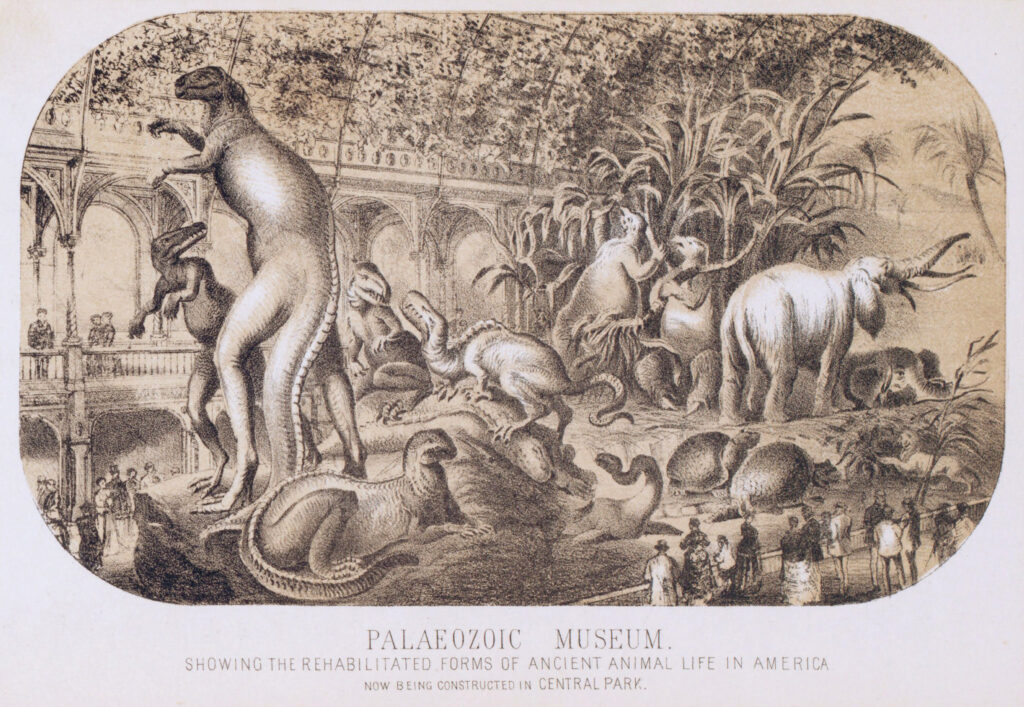

Indeed, the palace proved so popular that, when the fair ended, a group of businessmen bought it, had it dismantled pane by pane, and reconstructed it on an even grander scale in a park six miles south. Outside the palace, Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, commissioned an outdoor museum with sculptures of animals from Earth’s past. The exhibits, he felt, would have great civic value in educating the public. Albert was especially keen to include a newly named order of “fearfully great lizards,” the dinosaurs.

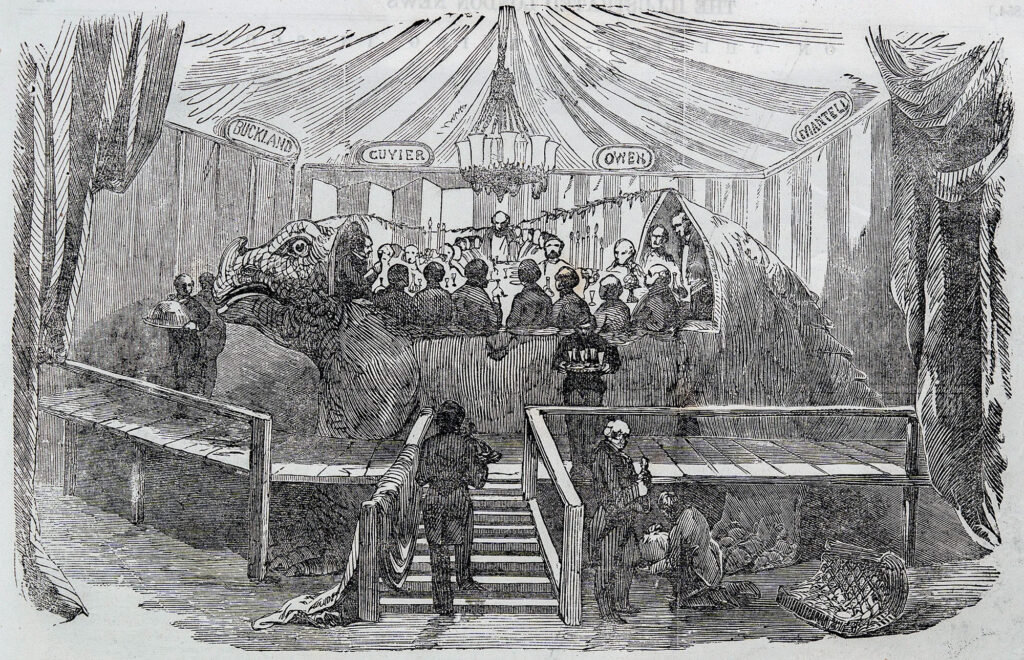

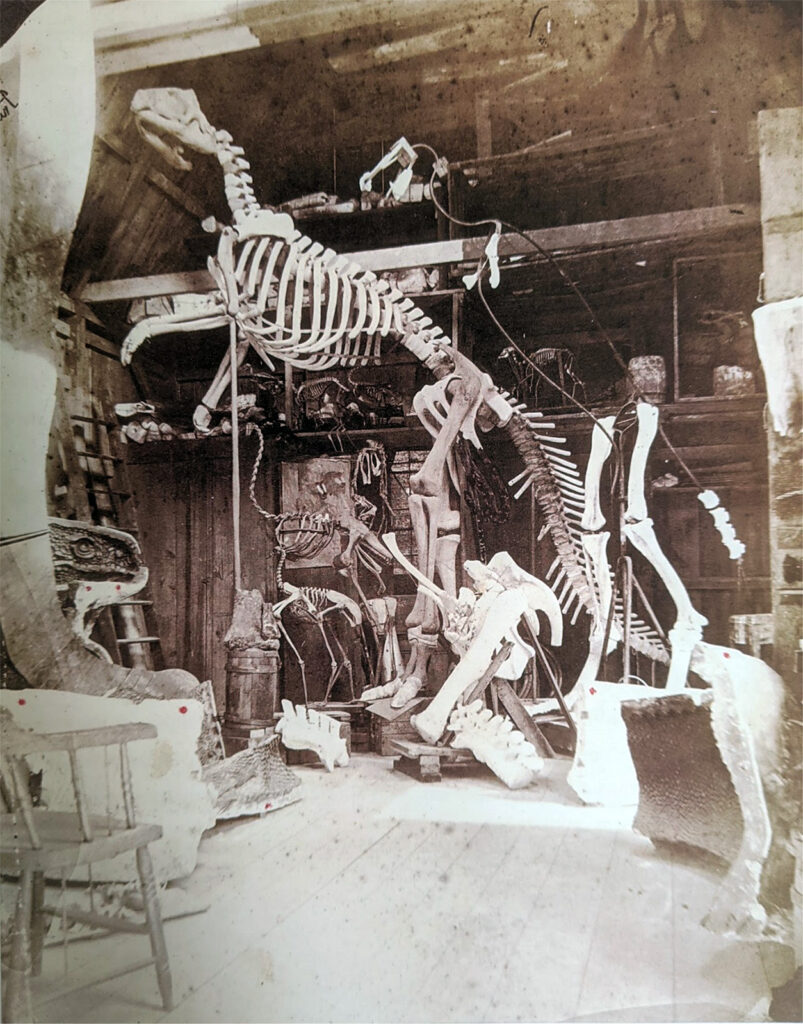

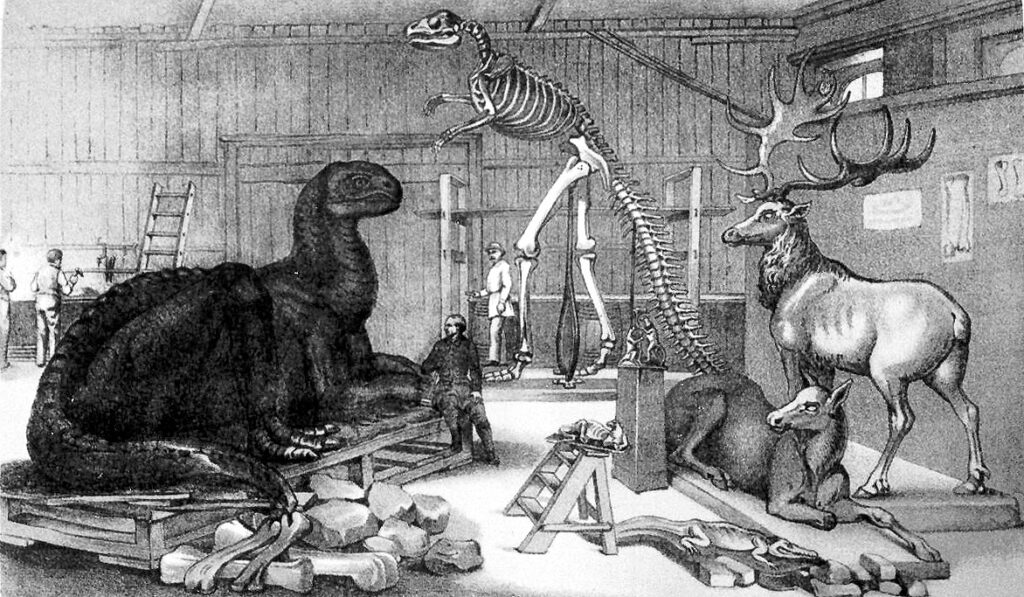

The artist who took on the commission was Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, a well-known sculptor and wildlife illustrator; he had done several pictures for Charles Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle. Hawkins drew on frogs and lizards as models for the fleshy parts of the creatures, sculpting them with wire, clay, and cement. For the most part, Hawkins made the beasts stout and squat, with fat, pachyderm legs and short necks. One looked as if a crocodile head had been fused onto a leathery lion. Others were covered in scales and had huge spikes running along their spines. Several brandished giant, gnashing teeth.