By fall 1942 the Allies were desperate. The Nazi invasion of France in 1940 had forced British troops to flee mainland Europe. The German-installed Vichy government controlled colonies in Africa and a fleet in the Mediterranean. Strategic talks between Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt ended in frustration as neither man believed that a direct assault on France was feasible.

Meanwhile the Soviet Union was losing hundreds of thousands of soldiers on the eastern front. Joseph Stalin appealed to the other Allied nations, asking them to mobilize for an invasion on the western front that would relieve the pressure on his forces. The only path into France was through the weaker defenses of Italy, and the only way to get there was through North Africa.

The Allies launched Operation Torch on November 8, 1942. In a three-pronged amphibious assault U.S. and British troops swept across Vichy-controlled North Africa, gaining a foothold that would afford access to the Mediterranean and eventually Italy. The coordination of thousands of boats, planes, and troop carriers was vital to the success of the two-day operation. But all of those guns, planes, and tanks might have been useless without an ability to predict the weather.

Meteorology, or weather forecasting, is a science that played a seldom-acknowledged role in World War II. Knowing future wind and weather patterns, even if only a few days in advance, allowed for better planning of shipping and airplane routes and for spying and reconnaissance. Fog and rain could be used to conceal tactical movement.

Henry Earl Lumpkin served in the U.S. Army’s Air Corps Weather Service during the invasion of North Africa. In his 1992 oral history with CHF he recalled helping pilots get from Miami to South America, and then across the Atlantic to Africa. “The Ninth Weather Squadron had weather forecasters stationed at every air base all along the route, ferrying war planes over and war-wearies back. We were forecasting route information for pilots.” Without Lumpkin and his peers to ensure the way was meteorologically clear, mounting Operation Torch would have been far more difficult.

Furthermore, the invasion of France on D-day would have been nearly impossible without adequate meteorology. British and U.S. forecasters had predicted a brief window of fair weather in the English Channel during which Allied forces attacked. The Allies reclaimed France and began racing the Soviet Union to Berlin. It was the beginning of the end for the German army.

While the war was winding down in Europe, the Japanese still controlled much of the Pacific, including the Philippines. General Douglas MacArthur’s invasion of the Philippine Islands required a mobilization of boats and planes at a time when Allied movements would be susceptible to typhoons and monsoon.

Leo Mandelkern, another CHF oral-history interviewee, trained as a meteorologist for the U.S. Signal Corps before being deployed to MacArthur’s campaign. “I was sent to the South Pacific, just about the time of the Philippine invasion. My job was to keep the meteorological equipment in that theater more or less functioning. That was not a trivial job because we had many problems with the high humidity and we didn’t have the technology to keeps things dry that we have now.”

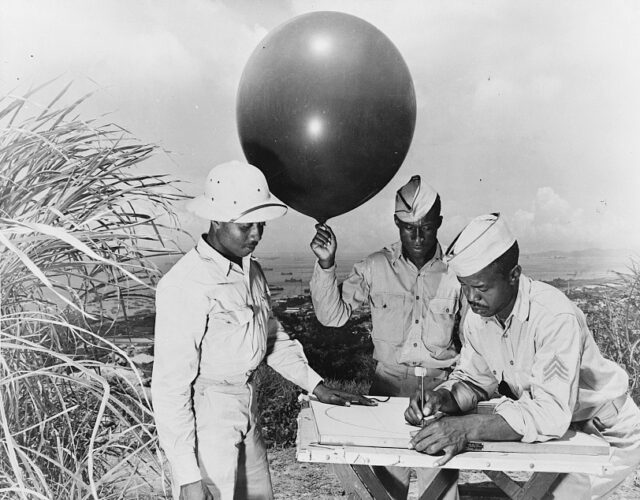

Chemists also played a role in ensuring Allied forces received timely weather reports. Herbert C. Brown worked with the Signal Corps while he was a graduate student at the University of Chicago. “So we were at the point of disbanding our research group [which was manufacturing uranium borohydride for the Manhattan Project] when we got a call from the Army Signal Corps. They said they had a problem generating hydrogen in the field.” Brown developed a safe, efficient method of producing hydrogen gas by reacting sodium borohydride and water. Balloons used hydrogen to carry instruments that could measure pressure, temperature, humidity, and wind direction and speed at different levels of the atmosphere. From these basic data meteorologists built their weather forecasts.

All three men left the military and meteorology behind after the war. Brown worked as a chemistry professor at Purdue University and earned the 1979 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work with boron- containing compounds. Mandelkern left the army to work at the National Bureau of Standards before moving to academia. Lumpkin spent his career with Humble Oil (later Exxon). When asked to compare his early experience with meteorology with his pursuits in chemistry, Lumpkin remarked, “The field of meteorology is a science. It’s not an exact science like mathematics. There’s some guessing involved. We still know that.”

The Science History Institute’s oral history collection includes interviews with women and men who have contributed to the advancement of scientific knowledge in the 20th and 21st centuries. For more information visit our Oral History Collections page.