My grandfather Sam Pelta was an adolescent in Poland when World War II began. The Nazis forced him to move with his family into the Lódz Ghetto, where Sam watched his mother die of sickness and starvation. Later the Nazis sent Sam to several concentration camps, including Buchenwald and Sonnenburg, where Sam was forced to build V-2 rockets. Yet it was through that slave labor that Sam managed to survive the Holocaust.

After being liberated by American soldiers at the end of the war, Sam moved to Szczecin, Poland, where he met my grandmother and where my mother Sylvia was born. Even after the war, Poland teemed with anti-Semitism and offered little in the way of economic opportunity. Sam and his young family fled from Poland to Germany, and lived for a year in the displaced-persons camp of Bergen-Belsen, near the former concentration camp where Nazis had murdered 50,000 people.

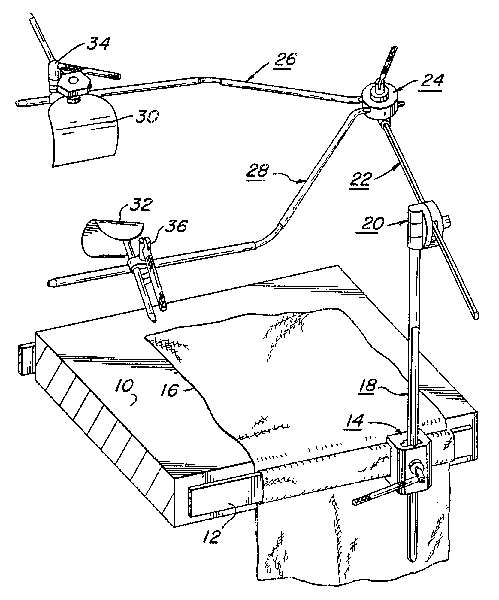

In January 1952, Sam immigrated to the United States along with my grandmother and mother, who was then 4 years old. They were among hundreds of thousands of displaced Jews who came to the United States during the massive refugee crisis that followed World War II. After immigrating through Ellis Island, my family settled in Philadelphia. Sam worked as a machinist for years while at night he went to school, first for his GED and then to study mechanical engineering. Ultimately, Sam went to work for Pilling, a medical instrument manufacturer. While at Pilling Sam patented a variety of designs, including clamps, supports, and adapters for surgical retractors.

An illustration from Sam Pelta’s patented surgical retractor support, which he designed for Pilling.

The irony is that Sam probably would not have had these educational and professional opportunities if it hadn’t been for the war. Unlike my grandmother, whose family had enough money to leave Poland for Russia when Germany invaded in 1939, Sam’s family was severely limited financially. Of course, Sam also wouldn’t have had these options if the United States had not changed the restrictive immigration laws that rejected Jewish refugees before and during the war because of their countries of origin—policies that are now echoed by the highly controversial executive order President Trump signed earlier this year to ban Syrian refugees along with immigrants from seven countries that are predominantly Muslim.

Sam’s story is similar to those of countless refugees who have sought asylum in the United States, many of whom have made profound contributions to American society, nowhere more so than in the sciences. A recent article in the Atlantic highlights the myriad connections between immigration and American inventiveness, as well as a direct correlation between increased immigration and economic growth. During the latter half of the 20th century, for example, there was a dramatic rise in the number of patents obtained by inventors like Sam who had immigrated to this country. In fact, according to “German-Jewish Emigres and U.S. Invention,” a 2014 study published by the American Economic Association, Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany contributed to a 31% increase in patents within their research fields after 1933. Those emigres collaborated with native-born U.S. scientists and trained the next generation of scientists. The benefits of this influx of knowledge and skill continue to compound to this day.

While the Trump administration’s initial order has been blocked by federal courts, the White House’s proposed immigration policies could be devastating for the U.S. industry and its scientific community, stifling research and innovation. The effects to the country’s scientific fields could last decades and could touch the highest levels of achievement. A 2016 study from the National Foundation for American Policy found that immigrants have won 31 out of 78 (or 40%) of the Nobel Prizes awarded to U.S. residents in chemistry, medicine, and physics since 2000. American immigrants have won more than three times as many Nobel Prizes in these fields between 1960 and 2016 than between 1901 and 1959. That staggering trend culminated in 2016, when all six of the country’s Nobel Prize winners in the sciences and economics were immigrants. By contrast, as a recent ThinkProgress piece that cited this study concluded, Germany’s atrocious treatment of Jews contributed to a sharp decline in Nobel Prizes for that country, both during and after World War II.

Protesters at an immigration rally near the White House in January.

Although my grandfather Sam passed away in 1998, I vividly recall how his creative spirit and determination carried over into his personal life. Often when my family and I would visit my grandparents, Sam would excitedly show us projects in his garage workshop or at his drafting table—a dining room–table extension he built to accommodate my expanding family at Passover seders; wooden lamps he carved for his grandsons; a pulley system he devised to light up the garage from the doorway. We were always proud of Sam’s ingenuity, just as we were proud of how outspoken he was about his Holocaust experiences, speaking in synagogues and community centers throughout the city. He tirelessly sought to remind people of the horrors endured by Jews, along with the prosperity that came from the United States opening its doors to refugees. If Sam were still alive, he undoubtedly would be speaking out about the current rise in anti-Semitism, as well as the consequences of Trump’s immigration ban.