Imagine you’re an engineer in the late 1990s. You’re flipping through a research journal, and a paper catches your eye. It’s about how cracks form and spread in concrete. It’s great stuff—really insightful. Your eyes soon jump to the top of the page, curious about the writer.

The answer startles you. The author is one Valery Fabrikant. But he’s not listed as a professor somewhere or a research scientist. He identifies himself as prisoner #167932-D. His home institution is a prison near Montreal. You’re left furrowing your brow in disbelief. Did a prisoner really write this paper?

Yes—a convicted murderer. Valery Fabrikant shot four colleagues in cold blood after failing to get tenure in 1992.

Maybe you’re thinking, Why would a journal publish this paper? Shouldn’t committing murder bar you from the scientific community?

According to many scientists, the answer is a firm no. In fact, in some ways, Fabrikant’s story goes to the heart of what science is and why its morals differ from the rest of society’s.

In December 1979, 39-year-old Valery Fabrikant showed up at the mechanical engineering department at Concordia University in Montreal. He was a short, slight man with graying hair and glasses. He claimed to be a political dissident from the Soviet Union seeking asylum. He begged the department chair for a job and got hired.

The department chair soon looked like a genius for hiring him. Fabrikant won grants from places such as NASA and published an amazing 25 papers during his first four years at Concordia, mostly on how materials respond to mechanical stress. Fabrikant was always boasting about how brilliant he was, and his track record seemed to back this up. The chairman promoted Fabrikant several times in quick succession, and in four years his salary jumped from $7,000 to $30,000.

Meanwhile, however, an uglier side of Fabrikant was emerging. If someone criticized his work, he’d scream at them. And not just once to blow off steam; he’d stalk and harass them. He once flew across the country to a conference simply to yell at a professor from a different college who had declined to hire him for a job. He also showed signs of paranoia, grousing that everyone around him was conspiring against him.

But as long as Fabrikant kept publishing papers and pulling in grants, his department chair looked the other way. He soon got another raise, to $46,000.

Should we tolerate good science from bad people?

By the late 1980s, a new department chair had taken over. Around the same time, three tenure-track jobs opened up at Concordia. Fabrikant begged the new chair for one of them. If he did not get it, he said he’d solve things “the American way” and mimed shooting a gun with his fingers. Despite this threat, he was given one of the jobs based on his publication record.

Scarily, this gun threat was not an isolated incident. He later told a department secretary that “the only way to get what you want in North America is to . . . shoot a lot of people.” In fact, he harassed so many secretaries around campus that a few had panic buttons installed beneath their desks, to summon security if he ever got belligerent or acted on these threats. Despite this behavior, in 1990 he got another raise, to $60,000.

Still, by 1991, some of Fabrikant’s colleagues were fed up with his tirades and harassment. They began holding secret meetings, discussing how to get rid of him.

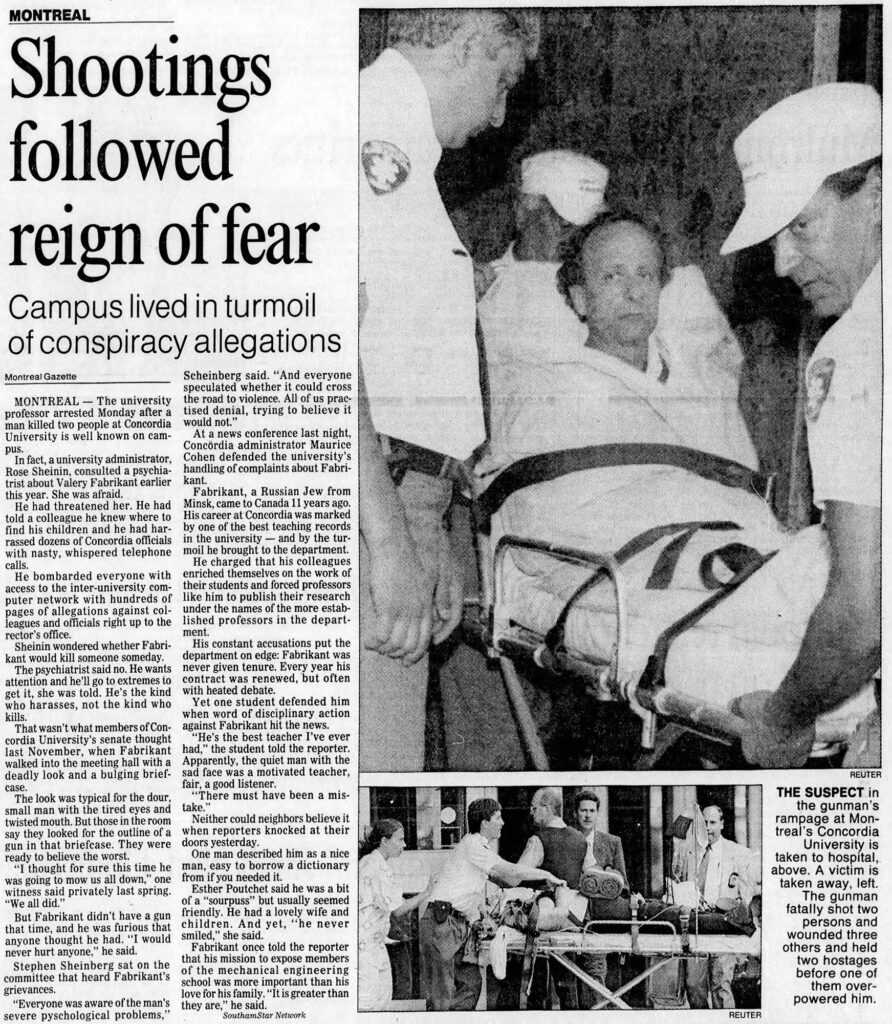

Meanwhile, a vice-rector at Concordia consulted an expert on workplace violence who told her that Fabrikant posed a serious danger. The vice-rector in turn told her boss, the rector. But the rector shrugged. Professors were eccentric. What could he do?

Somehow Fabrikant caught wind of these discussions. In response, he showed up at a faculty senate meeting with a huge envelope, the type artists might use to carry a portfolio. It looked like the ideal way to conceal a weapon. Someone called the police, who detained and searched Fabrikant. But there was no gun inside. He had been trolling them.

Things came to a head in 1992. A bloc within Fabrikant’s department began working to get him fired or to force him into early retirement. Fabrikant went ballistic in response, sending dark messages to people, saying that if he died and it looked like suicide, they shouldn’t believe it. He swore Concordia was plotting to murder him.

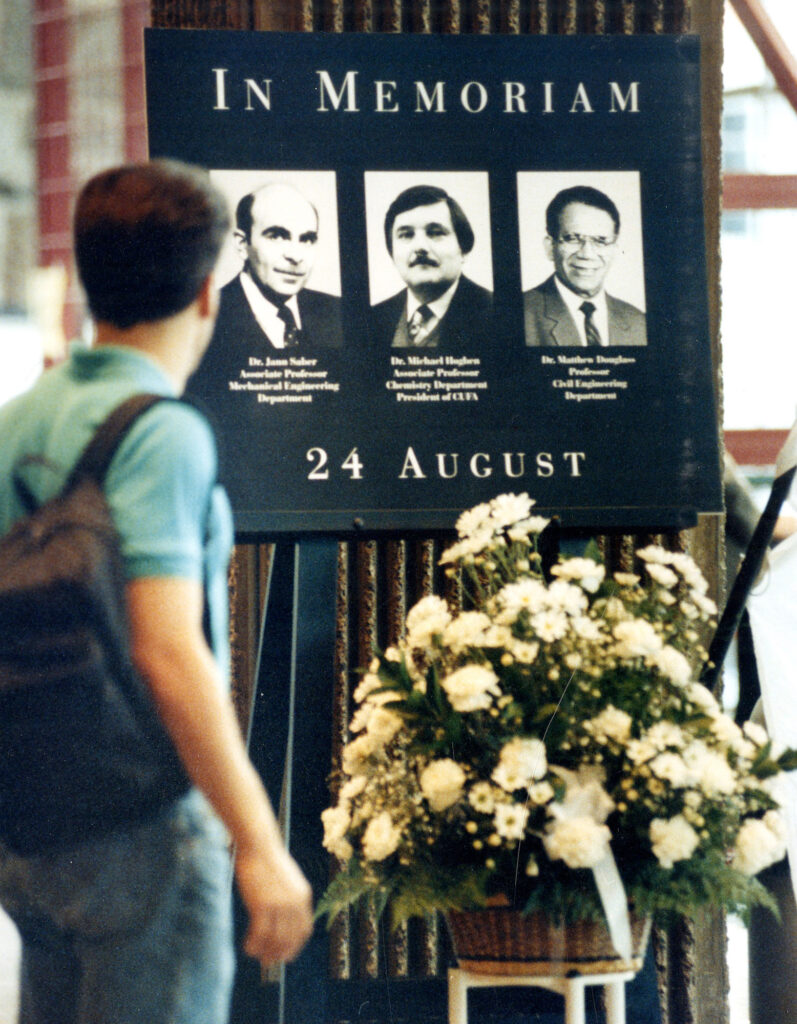

In reality, Fabrikant was the one plotting murder. On August 24, 1992, he rode the elevator to the ninth floor of the mechanical engineering building, where the faculty had offices. He was carrying a leather briefcase and opened it to retrieve a handgun. He began stalking down the hall, firing into open offices. He killed three people in quick succession and injured two others, one of whom died a month later. Somehow a colleague wrestled the gun away; unfortunately, Fabrikant had two more guns in the briefcase.

He took two people hostage in an office. There, he called 911 and demanded to talk to a TV news station. He admitted he had killed people but wanted to explain how the university had driven him to it—how he’d been persecuted.

After an hour on the phone, he put down his gun to stretch his neck. Bravely, one of the hostages sprang up and kicked the gun away. As Fabrikant lunged for it, the other hostage wrestled him down and pinned him until the police arrived.

Fabrikant was charged with four counts of murder, and, true to form, his trial was a narcissistic circus. He hired and fired 10 different lawyers before choosing to represent himself. He called 75 witnesses in his defense and got so belligerent with some of them that several started crying on the stand. He also called the judge a crook and was held in contempt of court six times. After five months, the jury found him guilty on all four counts and sentenced him to life imprisonment.

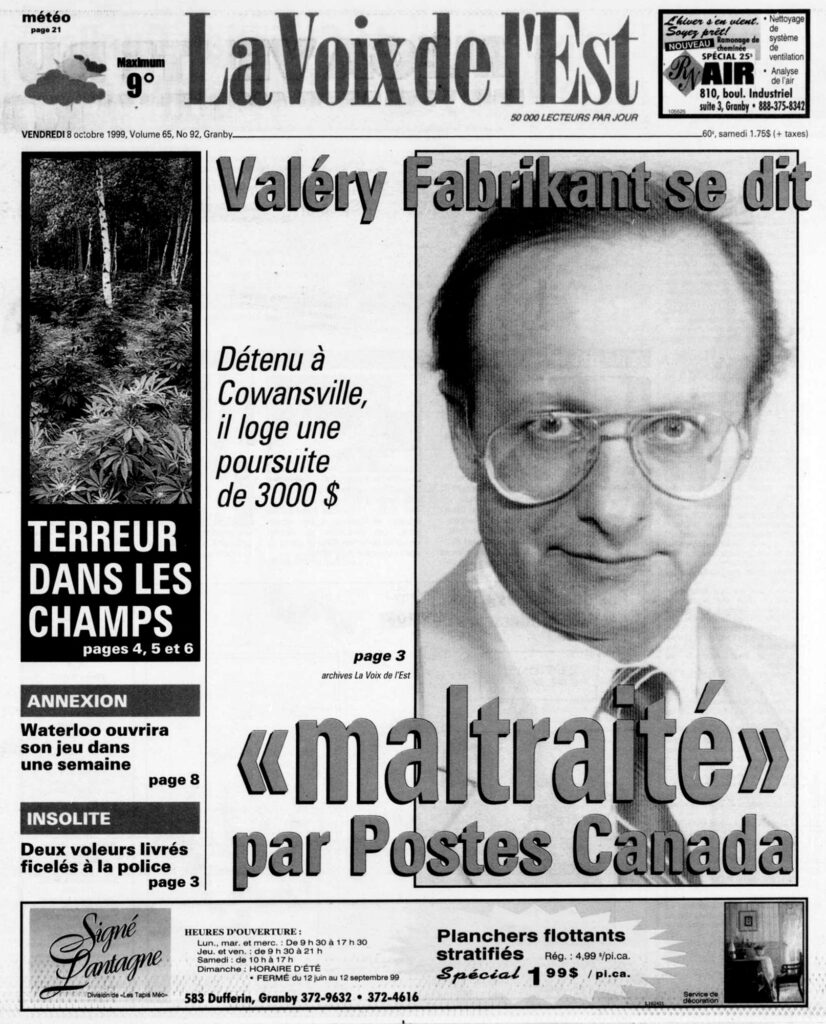

But Fabrikant had no intention of keeping quiet in prison. He began filing lawsuit after lawsuit against the state. More incredibly, he also resumed his scientific work.

With no access to a lab, he restricted himself to work on theoretical topics, like how cracks start and spread in concrete. And when submitting papers, he didn’t try to hide anything. He listed his address as his prison near Montreal and included his prisoner ID number. He submitted his first paper from prison in 1994. The journal editor reviewed it, decided it merited publication, and readied it for the printer.

Word soon got back to Concordia, whose administration was furious at the journal. How could they even consider publishing the work of a murderer? The families of Fabrikant’s victims protested as well.

The journal editor admitted he felt torn. Fabrikant had obviously done something heinous. On the other hand, his science checked out and was potentially quite useful. Concrete is, after all, one of the most common building materials in the world. Figuring out how it failed could save lives. Should he be suppressing such knowledge by not publishing it?

After some delays, the editor ultimately published the paper. And he wasn’t alone in doing so. Since 1996, Fabrikant has published 60 papers in 20 different journals, all from his jail cell. He even has a LinkedIn page.

This tacit acceptance of Fabrikant back into the scientific community has outraged many. Some drew comparisons to Nazi doctors running ghastly medical experiments on prisoners. They demanded to know whether the editors who published Fabrikant’s work would also publish papers by those monsters.

But others have pushed back, calling that a flawed comparison. The Nazi doctors were committing atrocities by their very research; they could not have gotten their data without the crimes. That wasn’t the case with Fabrikant. His work was independent of his crimes. Given this, should he really lose his right to publish?

Some critics still said yes. They raised concerns about how manipulative Fabrikant was. Perhaps his papers were part of a sneaky plot to impress a parole board and get himself out early. The new rector at Concordia (the old one was fired for not taking Fabrikant seriously as a threat) also argued that, in committing his crimes, Fabrikant had violated the rules of society. Science is part of society, not above it, and in breaking the rules of society, Fabrikant had forfeited his right to participate in scientific discourse.

It’s a strong point. But it also puts adherents in an awkward position. Like scientists, novelists and journalists are part of society. So should prisoners lose the right to compose books or articles? And if prisoners in general retain the right to publish, why should a prisoner who happens to publish science lose that same right?

What if Fabrikant had done research not in materials science but medicine? What if he developed a cure for malaria or HIV? Should society put its foot down and refuse to publish such cures simply because a vile, narcissistic murderer came up with them?

All of this leaves scientists in an uncomfortable position. Many scientists consider the search for truth a moral good in and of itself. They also consider the spread of knowledge a good thing. At the same time, scientists are human beings who live in societies with rules and ethical codes. So what should they do when values about truth and openness conflict with values about protecting lives?

To no one’s surprise, prison has done nothing to change Valery Fabrikant. He gets into petty fights with officials, and he’s filed so many lawsuits that the government declared him a “vexatious litigant” and barred him from filing any new ones. He’s also been denied parole twice; the board was apparently not swayed by his stellar publication record.

Fabrikant is now in his mid-80s, and his publication rate has been slowing. But even if he never publishes again, the questions that his terrible deeds raise—about whether we can and should tolerate good science from bad people—could haunt us for a very long time.