All Dayton Stoner wanted was to escape town for a bit. He was a biologist, mostly a bug and bird guy, and in June 1924 he took off driving from his hometown of Iowa City to Lake Okoboji near the Minnesota border, where he planned to spend a month working at a research station. His ornithologist wife and trusted assistant, Lillian, sat next to him. There were no car radios back then, so all they could do was sit back and enjoy the passing scenery.

Within minutes of leaving town, however, a discordant note interrupted their trip—a dead animal beside the road, possibly a redheaded woodpecker. A sad sight, but what could they do? They simply sighed and drove on, and most likely would have forgotten all about it.

Except, it happened again. Minutes later another bit of roadkill appeared, perhaps a squashed squirrel or rabbit. And even this might have been no more than a passing discomfort—except it happened again. And again, and again. Every few miles the Stoners spotted some new dead animal alongside the road—all of them flattened by automobiles.

Which got Stoner wondering. How much roadkill was he going to see? And this was just one back road in Iowa. What about the vast United States, with its millions of miles of roads? When Stoner started extrapolating, the numbers got very ugly, very quickly.

But Stoner was a scientist. He didn’t want guesses and extrapolations, he wanted data. So he enlisted Lillian’s help, asking her to keep track of every dead animal they encountered. Just like that, their road trip turned into a scientific venture.

His main question was this: What exactly were the consequences of the automobile on wildlife? The answer—and not just for Iowa, but for the world—would prove every bit as staggering as Stoner feared.

Given their experience as biologists, the Stoners could recognize most of the roadkill they passed without slowing down. There were snakes, skunks, cuckoos, robins, weasels, meadowlarks, cats. But every so often something was so squashed that they had to get out and inspect it to even guess what it might have been.

Overall, their 316-mile trip took two days, and they retraced the same basic route back home in July, with Lillian tallying the whole time. The final count floored them. They spotted 225 dead vertebrates from 29 different species. This included 53 redheaded woodpeckers, a vibrant-looking bird that fed on insects on the roadside and was often sluggish to take flight.

Stoner eventually wrote up a paper on his findings to sound the alarm about the growing danger of roadkill. And again, this was just one road in Iowa. What about elsewhere in the country?

Over the next few years the Stoners took road trips to Florida and New York and decided to gather more data. It quickly became clear that Iowa was not unusual. Everywhere they went they saw dead animals—mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians. The carnage extended nationwide.

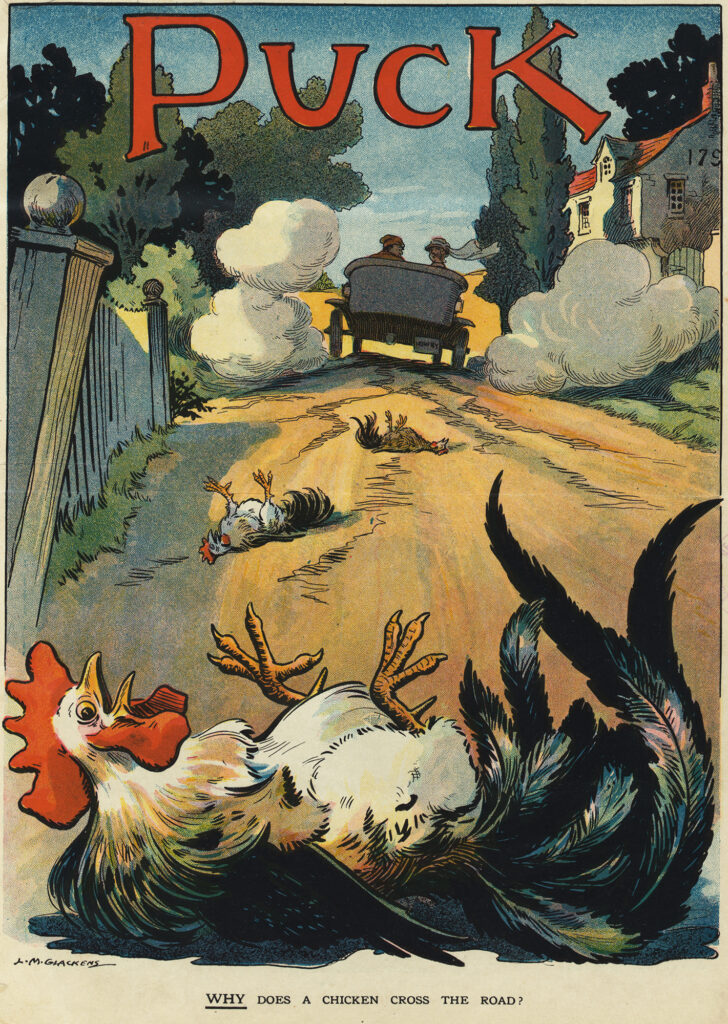

Now, strictly speaking, roadkill was not a new phenomenon. Even in the days of horses and buggies, turtles and other animals would sometimes get flattened. But as Stoner realized—and other biologists on their own road trips soon confirmed—cars were a whole new order of menace. After all, turtles are sluggish. But cars were nailing birds and bats, foxes and rabbits, toads and turkeys—much nimbler animals. Stoner was the first to sound the alarm about the growing danger, making him a sort of Rachel Carson of roadkill.

Things got even worse when the United States made concerted efforts to improve its roads beginning in the 1930s, mostly to help struggling farmers get crops to market. Before this, the United States had mostly dirt byways that limited people’s speed. (On Stoner’s trip through Iowa, he never topped 25 miles per hour.) But as government funds poured in to convert dirt roads into gravel roads and pave the gravel ones, speed limits jumped higher and higher. Animals that would have escaped being hit before now got clobbered.

With the expansion of the interstate highway system in the 1960s, cars finally overtook hunting as the biggest human killers of wildlife in the country. Today, an estimated one million vertebrates end up as roadkill every single day in the United States. That’s one death every 12 seconds.

Along with the frequency, the quality of accidents changed over the course of the 20th century, becoming far more deadly—including for humans. Hitting a woodpecker or skunk is unfortunate and might cost a motorist a grille or windshield. But people will probably walk away from that accident. With deer, it’s a different story. They’re heavy enough to cause fatalities, especially at the high speeds necessary to hit deer.

Deer were attracted to highways for one main reason. As part of general safety measures, road engineers often added medians and verges to highways—strips of grass to the side and in the middle. Unfortunately, that soft, tender grass proved to be ambrosia for deer. They started seeking out roadways to feast. And the more deer that came, the more collisions that resulted.

Engineers tried to fix the problem by planting less tasty grasses. They also stopped salting roads during the winter, since the deer sometimes came to lick the salt for nutrients. Along the deadliest stretches, engineers even fenced off roads for miles to physically block deer from crossing.

None of it worked. The deer kept eating the grass and learned to circle around or even crawl underneath fences. Deer–car fatalities kept rising and rising.

Other animals suffered even more than deer, and some have even been pushed to the brink of extinction. The most prominent example is the Florida panther—a tawny, majestic cat. In the mid-1900s overhunting and rapacious development in southern Florida whittled its population down to about 60 in the wild. Cars seemed poised to finish the job. In 2021 motorists killed at least 21 panthers, and 8 more in the first two months of 2022—an estimated one-eighth to one-quarter of their population in the wild.

North America isn’t alone, either. Wherever there are roads, there’s roadkill, and automobiles threaten dozens of endangered species around the world. Even huge, seemingly immovable beasts, such as yaks, tigers, and elephants, get killed. (This carnage doesn’t even include insects—several trillion of which get splatted onto grilles and windshields every year.)

Probably the most dangerous country for roadkill today is Brazil. Both the government and powerful business interests there have pushed hard to build new roads into the Amazon, threatening scads of animals that have never encountered an automobile.

The worst-hit animal has been the goofily chimeric giant anteater, with its shaggy, Snuffleupagus snout and razor-sharp claws. Giant anteaters are adventurous (or foolhardy) enough to blunder onto roads but not agile enough to dodge cars. Their population has been estimated at around 5,000—but cars and trucks kill roughly 300 every year. That’s not favorable math, and there’s a very real chance that, as highways continue to branch into new areas, we’ll be talking about giant anteaters in the past tense in a few decades.

Other Brazilian animals face threats as well, including raccoons, caimans, foxes, and raptors. In fact, if the U.S. figure of a million dead animals per day sounds horrifying, roadkill in Brazil is 10% worse—1.1 million deaths per day, or 400 million each year.

Is there anything we can do about the carnage of roadkill? The obvious solution is to stop building roads, especially into crucial habitats. But that’s unlikely to happen, especially in the developing world where roads often mean jobs in logging and mining for people with few other prospects.

Amazingly, some species have already evolved to suffer fewer accidents. One 30-year study in Nebraska found that the wings of cliff swallows are now 4% shorter. This helps them take off faster and change directions more deftly in midair, all the better to dodge the 18-wheelers roaring past their homes.

Waiting for animals to evolve is hardly a solution, however. Roads can and should get better. The most promising measure involves building grassy tunnels beneath highways, or grassy bridges over them, to give deer, panthers, and anteaters safe passage. These measures can’t eliminate roadkill entirely, and they do cost money: $200,000 to $400,000 for an underpass, and $2 million to $4 million for bridges. But those are largely one-time costs. Meanwhile, deer collisions alone cost an estimated $8 billion per year in damages and cleanup in the United States. Under- and overpasses are also passive measures that require no elaborate monitoring or ongoing effort, nor changes to animal behavior. They’re also highly effective: in Banff National Park in Canada, such passes have eliminated 80% of the roadkill.

When we think about the impact cars have on wildlife today, we usually think about exhaust and smog, or greenhouse gases and the destruction of habitats as the result of global warming. But even a century after Dayton and Lillian Stoner’s road trip, few people appreciate the blunt-force trauma automobiles inflict. We can make cars cleaner and more eco-friendly, but speed always kills.