In 1960 hundreds of filmgoers attended a movie that stank. As Scent of Mystery flashed onto the screen, fragrances wafted through a tangle of tubes beneath the seats. “Best are the easily recognized ones: perfume, mint, wood shavings, roses,” wrote an Associated Press film critic in the audience. “Some—pipe smoke, shoe polish, horses—are well nigh nauseating.”

It was a strange but stimulating time in the history of film. Midcentury movie studios were looking everywhere for something new. Decades had passed with little innovation: talkies had been an industry standard for more than 20 years, while color film was already five decades old. Even 3-D, or “stereoscopic,” films seemed like old news by the late 1950s. Fleeting widescreen technologies, such as Cinerama, Cinemascope, and Vistavision, each tried to outdo the other.

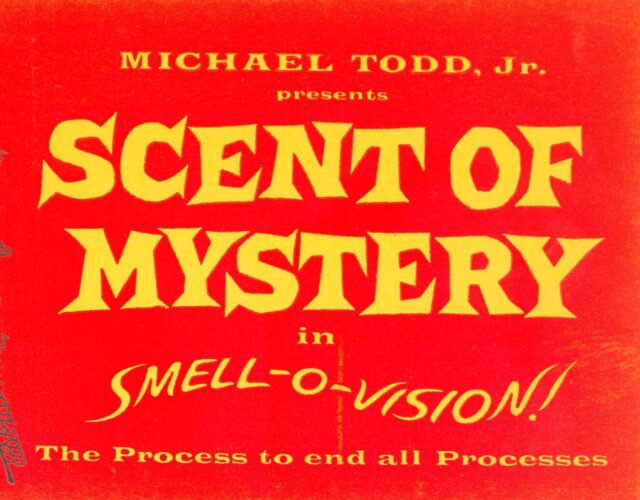

A few film producers chose a different strategy—as in the case of Smell-O-Vision, the technology behind Scent of Mystery. “You have to provide unusual entertainment to get people out these days,” said its creator Michael Todd Jr. in a 1959 interview. “And that’s what we have.”

For a brief period, thanks to a few well-publicized films, scent became cinema’s third sense. Producers and perfumers worked together to distill smells ranging from oranges to oil paint, cut grass to garlic.

From the very beginning, scented cinema was the butt of bad jokes. In 1960 the Milwaukee Sentinel imagined the same technology applied to television. “The varied odors from the commercials could be very nauseating,” declared the newspaper’s film writer, “such as Mr. Clean cleaning out a dirty old sink.” During beer advertisements “the very smell of the hops would make you dash out to the refrigerator for a can, missing most of the commercial.”

Todd took the pungent publicity in stride and stubbornly defended his “smellies”—a name that humorously depicted them as a natural progression from talkies. “We’re not pretentious about it,” Todd told the Associated Press. In another interview he remarked, “We don’t expect our picture to win any art awards . . . but I guarantee audiences will have fun.”

Before talkies, directors relied on lighting, costumes, and intertitles (interstitial text between shots) to help the audience recognize heroes and bad guys. The addition of auditory markers, such as accents, footsteps, and ominous music, offered similar guidance. Scent of Mystery went a step further by using different smells for good guys and bad guys. In one scene the audience smells the hero’s cup of coffee—but when the villain takes a sip of his own coffee, the audience smells brandy.

The mechanics and chemistry of Smell-O-Vision were kept under wraps, but it was possible to get a whiff of Todd’s technology from the interviews he gave. Early scented films, such as Behind the Great Wall, which used a scent system called Aromarama, piped smells through the theater’s ventilation system. But Hollywood films were tightly cut, so a given shot might only last 10 or 20 seconds. If the camera zoomed out from a picnic basket to a field of grass, Aromarama couldn’t keep up.

Todd’s solution was to deliver scents directly to each member of the audience. “The odors are piped individually to each seat, instead of through the air conditioning,” he remarked in an Associated Press interview. “With this system the odors change fast.” In 1959 he estimated that the equipment would cost $25 to $30 per seat. By comparison a movie ticket at the time would have cost well under a dollar.

According to Tammy Burnstock, an Australian film producer who recently revived the Smell-O-Vision process, the smells for Scent of Mystery were generated by a “smell brain,” a round device that held several vials and produced “an automated smell track, like a soundtrack.” Burnstock has been drawn to scent since she studied Smell-O-Vision as a film student in the 1980s. She was struck by smell’s tight links to memory and emotion. Whether appetizing or abhorrent, smells have the power to evoke moments from the past. “My smell from childhood is rain on concrete,” she says. “For some people, lavender is relaxing. For other people, it’s kind of old lady sock cupboards.”

To reconstruct Todd’s technology for a recent screening of Scent of Mystery, Burnstock enlisted the help of Saskia Wilson-Brown, who has spent the past several years creating scents for museums and cultural institutions. Because Wilson-Brown is interested in introducing scent to art installations and other custom projects, she stayed away from professional perfumeries and taught herself to blend fragrances.

“I’ve sat down and blended now for five years, almost every day,” she says. Wilson-Brown found the work intimidating at first, in part because perfumers use specialized language—in the same way that a sommelier might describe the complexities of a wine.

It was this sensitivity to the creative potential of scent that Wilson-Brown has tried to bring to Burnstock’s project. Though the pair had a list of the odors used in the 1960 production, none of the original fragrances or their chemical formulas were available, only names, such as “happy odor of baking bread,” “the faint smell of a yellow rose,” and “the sharp volatility of gasoline.” As a result, Wilson-Brown had to blend them by hand in her Los Angeles studio.

An advertisement for the Smell-O-Vision movie, Scent of Mystery, Hollywood producer Michael Todd Jr.’s attempt bring a third sense to the cinematic experience.

Wilson-Brown’s workshop, located on a side street in Chinatown and a few miles from Hollywood, is a large open room with tables in the center and vials of solution along the wall. Each vial contains specific aroma molecules—some natural, some synthetic—that are diluted with alcohol. Blending new scents, she says, basically means using pipettes and beakers to mix precise amounts of one chemical with another. A typical scent might include half a dozen ingredients.

For example, for one scene from Scent of Mystery that was shot in an art studio, Wilson-Brown tried different molecules that mimicked the scents of linseed oil (for the paints) and cedar (for the smell of freshly sharpened pencils). Her first experiment was a “sort of a sketch” of a scent—“almost a caricature,” says Wilson-Brown. The wrong ratio might make the scent too lemony or too oily, but over time tinkering brought the fragrance closer to completion.

Some smells are simpler to produce than others. “Cut grass is really easy—there’s a couple of very specific molecules,” Wilson-Brown says. “But things like bread or meat, they get a lot more complicated.” She recently tried to blend the odor of fried chicken—which, she says, involved experimentation with “horrible smelling” fatty scents.

One of the reasons that the scents in Scent of Mystery are, well, mysterious is that the perfume industry has traditionally been controlled by fragrance houses, such as Givaudan, Firmenich, and International Flavors and Fragrances, that develop smells for perfumes, cosmetics, and sometimes foods. Many houses have laboratories dedicated to discovering new scent molecules, as well as mixing rooms where the molecules are blended. New recipes are patented and proprietary; secrecy gives fragrance houses an edge on the competition.

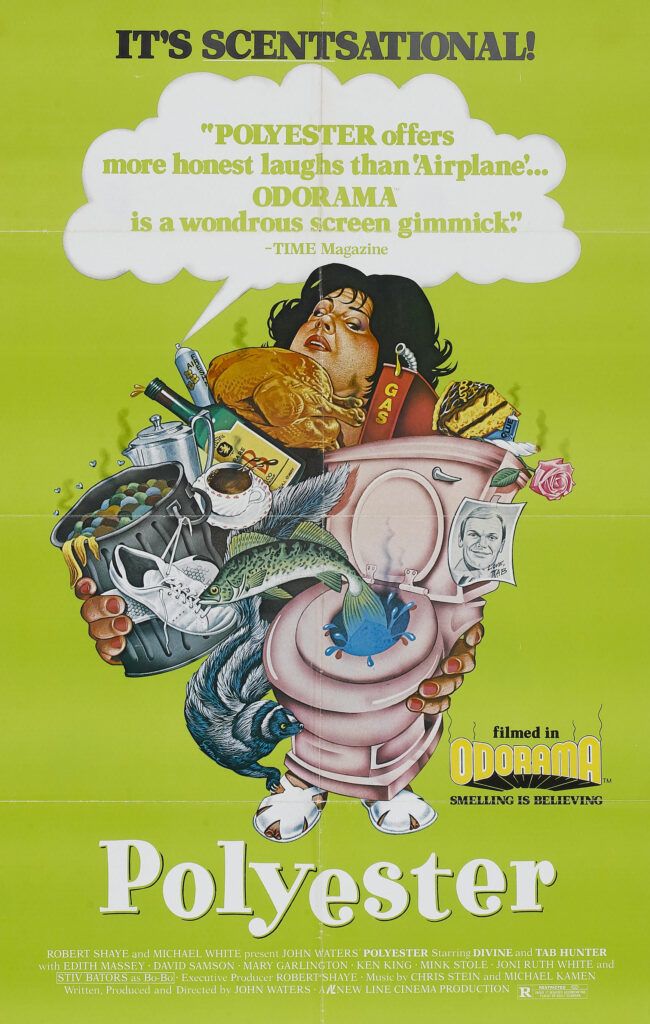

Perhaps that’s the real link between fragrance and film. The race to design alluring scents, like the race to produce blockbuster movies, starts with technological competition and behind-the-scenes innovation. The process of creative competition continues to this day: 3-D films are back; theaters try to distinguish themselves with large-format screens and immersive surround sound. Perhaps the modern equivalent of Smell-O-Vision is virtual reality.

After a while, though, even new and exciting scents tend to fade into the background. Smell-O-Vision was largely forgotten after its debut. The work of Burnstock and Wilson-Brown aims to change that—and although the revival of scented cinema remains small-scale, they’ve staged several well-attended screenings in Los Angeles, England, and Denmark. Whatever happens to scented cinema in the years to come, perhaps it’s okay if Michael Todd Jr. and his contemporaries aren’t viewed as visionaries. After all, it wasn’t the sights that they cared about.