Robert Ho Man Kwok just had a simple question: why did he feel so lousy after eating at restaurants that served Northern Chinese food?

His heart would start racing, and he would feel weak and numb afterward. After noodling on the idea for a while, he came up with a few possible culprits for his symptoms. But Kwok, a pediatrician in Maryland, knew he didn’t have the expertise to resolve the question. So he wrote a letter to the august New England Journal of Medicine, asking whether any other doctors had thoughts on the matter.

Boy, did they. Kwok was simply trying to spark some discussion to answer his question. He had no idea that instead he would spark decades of national hysteria that would see one of the most popular seasonings in the world—monosodium glutamate, or MSG—demonized as a deadly toxin.

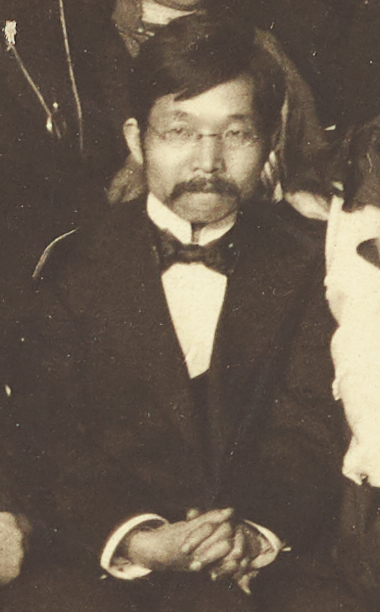

A Japanese chemist named Kikunae Ikeda invented MSG, which looks like tiny crystals of brown or white sand, in the early 1900s. He then founded the Ajinomoto corporation to mass-produce the seasoning.

Kikunae Ikeda, 1900.

After some initial struggles to find customers—restaurants and soy-sauce brewers shunned it as untraditional—Ajinomoto found success targeting homemakers. To make its product fashionable, the company packaged MSG in elegant glass bottles, like perfume, and pushed them especially hard in finishing schools for the daughters of Japanese elites. The Japanese government also helped. A seasoning invented by a chemist had an air of technological sophistication that appealed to officials intent on modernizing the country through science and technology. As a result, MSG seasoning exploded in popularity in Japan.

As Japan colonized much of East Asia in the early 1900s, MSG followed the sword. Ajinomoto’s products became associated with Japanese imperialism, especially in China. Nevertheless, many Chinese people liked MSG, which made food taste more savory. Knockoff brands arose to compete with Ajinomoto and soon began dominating the market.

It’s through China that MSG first entered American cuisine. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, nationalist backlash against the Japanese was swift and brutal. President Roosevelt incarcerated more than 100,000 innocent Japanese Americans in internment camps, and the public developed a newfound sympathy for China, which had suffered under Japanese occupation for decades. Many Americans without Chinese heritage began exploring Chinese culture, including visiting Chinatowns and eating at Chinese restaurants. As a result, by the late 1940s MSG-rich Chinese food was growing popular stateside. American food manufacturers began quietly adding it to canned soups and TV dinners to add some zip, and the military put MSG in soldiers’ MRE rations. Everyone seemed happy.

Then came the 1960s. Books such as Silent Spring, while focused on pesticides, suddenly made people wary of “chemicals,” including dyes, artificial sweeteners, and other food additives. In a time of mistrust and suspicion, a “foreign” chemical like MSG became an easy target.

The MSG panic began in April 1968, when Kwok wrote the letter to the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) outlining his symptoms (racing heart, weakness, numbness), and fingering three possible culprits—salt, cooking wine, or perhaps MSG.

A month later, the NEJM printed 10 responses from other doctors. Like Kwok, the doctors reported discomfort after eating Chinese food, either in themselves or in friends or patients. (Unlike Kwok, none distinguished between Northern and Southern Chinese cuisines; they lumped all Chinese food together.)

The symptoms catalogued in the letters included fainting, back spasms, sweating, dizziness, flushed skin, and a numb jaw. Puzzlingly, though, no two letter writers listed the same symptoms. And the possible links between them was anyone’s guess: they appeared all over the body and came on at widely varying times after eating.

Stranger still, some doctors declared the syndrome occurred only in certain geographical locations. New York and Southern California were deemed risky, while Hawaii and London were absolved. Nor could the doctors agree on the instigating ingredient. One blamed duck sauce, another frozen veggies. Others fingered mustard, wonton soup, or puffer-fish venom. One even blamed the physical strain of Westerners struggling with chopsticks. Of note, one neurologist explicitly absolved MSG, noting that he cooked with it all the time at home and never felt a thing.

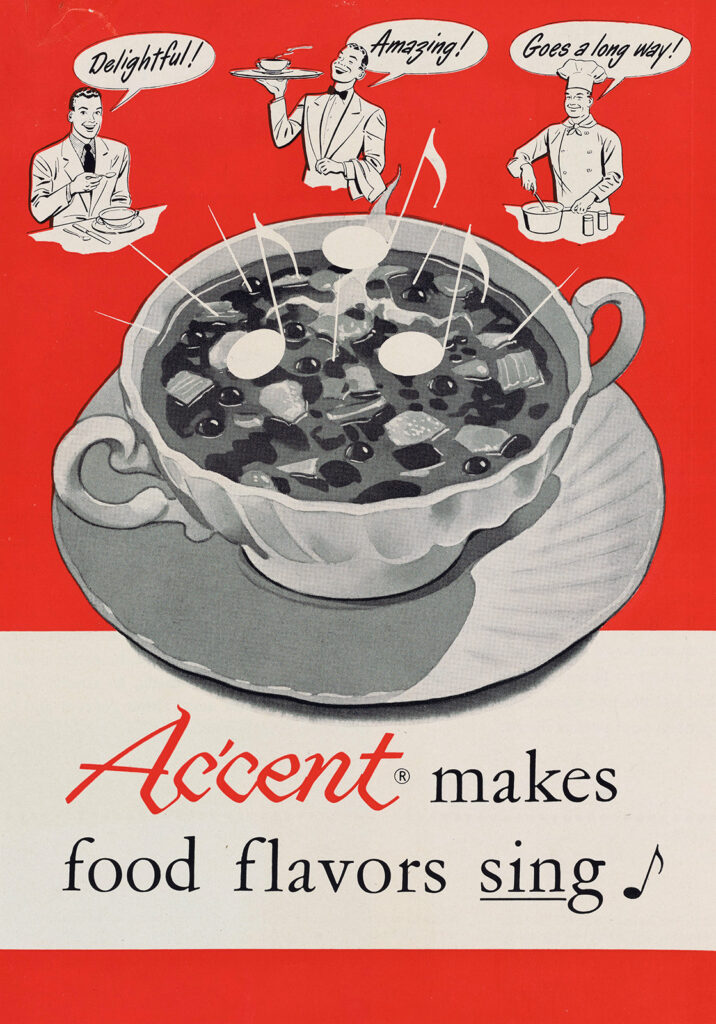

Detail from a promotional pamphlet Aji-No-Moto brand MSG, ca. 1930.

Given the inconsistent symptoms and the anecdotal nature of the reports, it’s hard to understand why medical scientists didn’t dismiss the purported syndrome as fictitious. And in fact, the NEJM editors implied as much in a smirking editorial accompanying the replies, wondering aloud about the odd geographical spread, among other issues. Newspapers, however, didn’t get the joke and began running breathless stories about so-called Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.

At this point, no one had isolated MSG as the culprit. That changed once a series of dubious scientific studies began appearing in July 1968.

The first study was peculiar because its author, neurologist Herbert Schaumburg, had written the letter to the NEJM in May that absolved MSG, since he cooked with it at home. In that letter Schaumburg also emphasized that the syndrome was not a big deal; symptoms passed in five minutes, and he usually finished his meal after.

Suddenly, however, Schaumburg was singing a different tune on MSG, backed by some questionable experiments. In a July letter to the NEJM, he reported visiting a local Chinese restaurant for several consecutive days for breakfast, lunch, and dinner and systematically eating everything on the menu in a deliberate attempt to induce symptoms. Lo and behold, he found what he wanted: he experienced symptoms after eating wonton soup and hot and sour soup, both of which he determined (it’s unclear how) contained MSG.

Schaumburg also gave MSG to three blinded “volunteers,” all of whom he said reacted badly. One of these volunteers, however, was Schaumburg himself, which means he wasn’t truly blinded. As for the others, Schaumberg admitted that several of the symptoms he observed (faintness, racing hearts, tears, nausea) can also result from anxiety. Like, say, the anxiety someone might feel when a doctor gives them a substance he claims will induce distressing symptoms.

Seven months later, in February 1969, Schaumberg and three colleagues published a more formal, but still flawed study with several parts. The first involved six volunteers who had all suffered “attacks” at a Chinese restaurant previously. Two were taken back to the restaurant and suffered attacks while eating a soup rich in MSG. The other four were given pure MSG to eat and suffered attacks as well.

Schaumberg’s team then ran a second, unblinded experiment that involved giving pure MSG to 56 people. Each was asked about three main symptoms—burning, facial pressure, and chest pain. The presence of any one symptom was taken as a sign of MSG toxicity. Fifty-five of the volunteers showed signs, although only a handful experienced all three.

In a third part, the team took nine volunteers, all of whom had a history of headaches, and placed three bowls of chicken broth in front of them. One of the bowls contained MSG, with the broth salted to mask its taste. Just two of the nine reported headaches.

The study’s flaws are myriad. The first and third parts had tiny sample sizes, six and nine people. The second wasn’t blinded, and Schaumberg had people consume MSG on an empty stomach. Consuming large amounts of any condiment on an empty stomach could cause discomfort, nausea, or worse. Imagine chugging malt vinegar or swallowing cayenne pepper alone.

Furthermore, Schaumberg’s team did not always use representative samples and did not adequately control for psychological factors. In the first part, they brought susceptible people to a restaurant where they’d already suffered attacks—which could itself induce distress. In the third part, the team used people who already had a history of headaches. And even then, just two of nine showed symptoms—probably because of adequate blinding. Worst of all, in the second part, volunteers once again knew they might be ingesting a potentially noxious substance, which could cause anxiety on its own. The power of suggestion is real.

Despite these flaws, Schaumberg’s team insisted that MSG “is not a wholly innocuous substance.” Another doctor, Robert Olney, a psychiatrist at Washington University in St. Louis, then pushed things even further, claiming that MSG caused brain damage in a truly terrible study published in May 1969.

To start, Olney injected albino mice pups with a solution of up to 4 milligrams of MSG per gram of body weight. He then euthanized the mice and reported finding brain lesions.

In a second experiment, Olney injected 20 more mice with even higher concentrations of MSG (up to 7 milligrams per gram of body weight) and followed them through maturity. These mice were compared with 18 control mice who did not receive injections. Olney reported that the MSG mice were sterile and stunted and gained weight more rapidly, despite eating less food. They were also “lethargic” and had coats that “lacked the sleekness” of control mice.

Based on these findings, Olney declared that pregnant women should avoid MSG, due to potential damage to fetuses.

Four months later, three physicians responded to Olney’s study with several damning criticisms. First, the amount of MSG Olney injected was excessive—the equivalent of an adult human eating a whole pound of MSG in one sitting. (In a typical American diet, the doctors noted, people consumed around 0.01 milligrams of MSG per gram of body weight daily, compared to Olney’s 7 milligrams per gram.)

Moreover, the critics noted, humans don’t inject MSG under our skin; we eat it, which allows the acids and enzymes in our stomach to break the chemical down. They also derided Olney’s methods, noting that he should have injected the control mice with saline or another solution, since injecting even harmless fluids could still crush or damage vulnerable organs.

Other criticisms could be levied against Olney as well. First, mice aren’t people—you can’t simply extrapolate from one species to the other. Second, Olney was not blinded to which mice received MSG injections and which did not. This could introduce bias in measuring the animals’ size or determining whether one was more lethargic. Finally, in formulating his warning Olney ignored the possibility that the placenta in pregnant mothers, or blood-brain barrier in all humans, could filter MSG and prevent damage. In fact, modern studies have determined that “almost no ingested glutamate/MSG passes from gut into blood, and essentially none transits placenta from maternal to fetal circulation or crosses the blood-brain barrier.”

Unfortunately, words of caution and quibbles over controls did not deter the likes of Olney. The media proved even less cautious. Guess which story got more play? That something you’ve eaten your whole life is perfectly safe? Or that some “foreign” chemical in food makes you fat and sterile and destroys your baby’s brain? As a result, the panic over Chinese Restaurant Syndrome kept building and building. Ralph Nader began pushing to ban MSG in baby food; other activists pushed to ban it altogether.

To be clear, since the 1960s, scientists have conducted many careful follow-up studies on MSG with proper controls and blinding. And the vast majority of evidence suggests that MSG causes no harm. The critics of Schaumberg and Olney have been vindicated: their studies looked shaky then, and seem even worse now.

And beyond the science, the idea that MSG poisons people violates common sense. Americans consume around 500 milligrams of MSG per day on average. People in East Asian countries consume 1,700 milligrams a day—over three times as much. But no one there gets sick from MSG. As one wag put it, “Why doesn’t everyone in China have a headache?” The answer is simple: because they don’t expect to and were never told they should.

Indeed, people in the United States were consuming MSG in canned soups and TV dinners for decades without batting an eye. Only when MSG was linked to Chinese cuisine did Americans panic. (This last point also undermines the occasional suggestion that the real culprit in Chinese Restaurant Syndrome is the high salt content in Asian food. Pepperoni and cheese are loaded with sodium, but no one ever talks about Italian Pizzeria Syndrome.)

Thankfully, while the fear of MSG continues to echo online, much of the negative hype has died away. It’s still worthwhile reflecting, however, on how such shoddy science became an article of faith in medicine. Kwok, Schaumburg, and Olney may have sincerely wanted to help people. But their story shows that even scientists are suspectable to rumors, hysteria, and urban legends that defy common sense.