The strawberries we eat are the work of a spy.

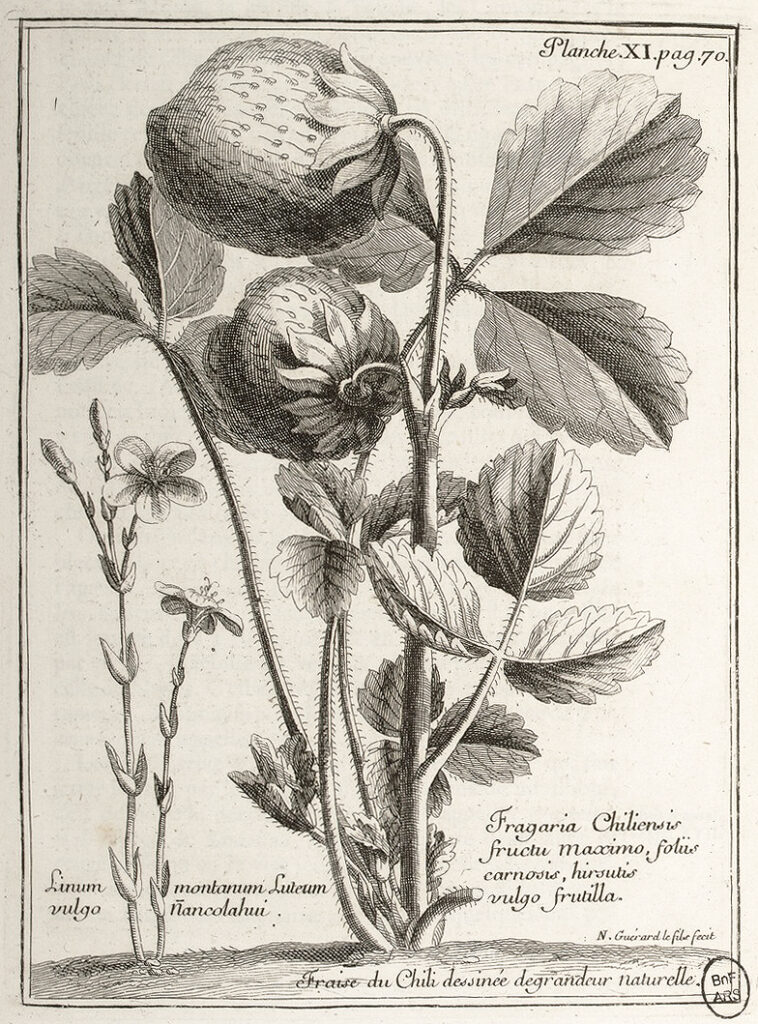

In 1712 French King Louis XIV sent Amédée-François Frézier, an officer in the French Army Intelligence Corps, to Chile and Peru, both colonies of France’s rival Spain. Posing as a merchant and ingratiating himself with the Spanish governors, Frézier covertly studied the countries’ military fortifications. But he also observed the local flora and fauna, sketching plants into his journal.

One day, Frézier happened across berries on a field. They looked familiar yet massive: strawberries. These berries also grew in Europe and North America, but there they were puny compared to the Chilean strawberries, which were “as big as a walnut, and sometimes as a hen’s egg,” Frézier marveled in his journal. The Chilean berries were also paler and tasted less sweet.

He successfully brought five plants back to France, where one was planted in the royal gardens of Versailles, among the rest of the king’s strawberry collection. Soon, this Chilean strawberry spontaneously cross-pollinated with a neighboring bush from Virginia. The result was a hardy plant with large, sweet berries—from which all modern commercial strawberries would descend.

Each year, Americans eat around 2.4 billion pounds of those strawberries, more than six pounds per person. They also consume 13 pounds of bananas, nine pounds of apples, and about five pounds of fresh grapes. And Americans aren’t the only ones eating lots of fruit. Globally, the combined production of cherries, blueberries, pineapples, pears, oranges, peaches, plums, and other fruit reaches more than 900 million tons per year.

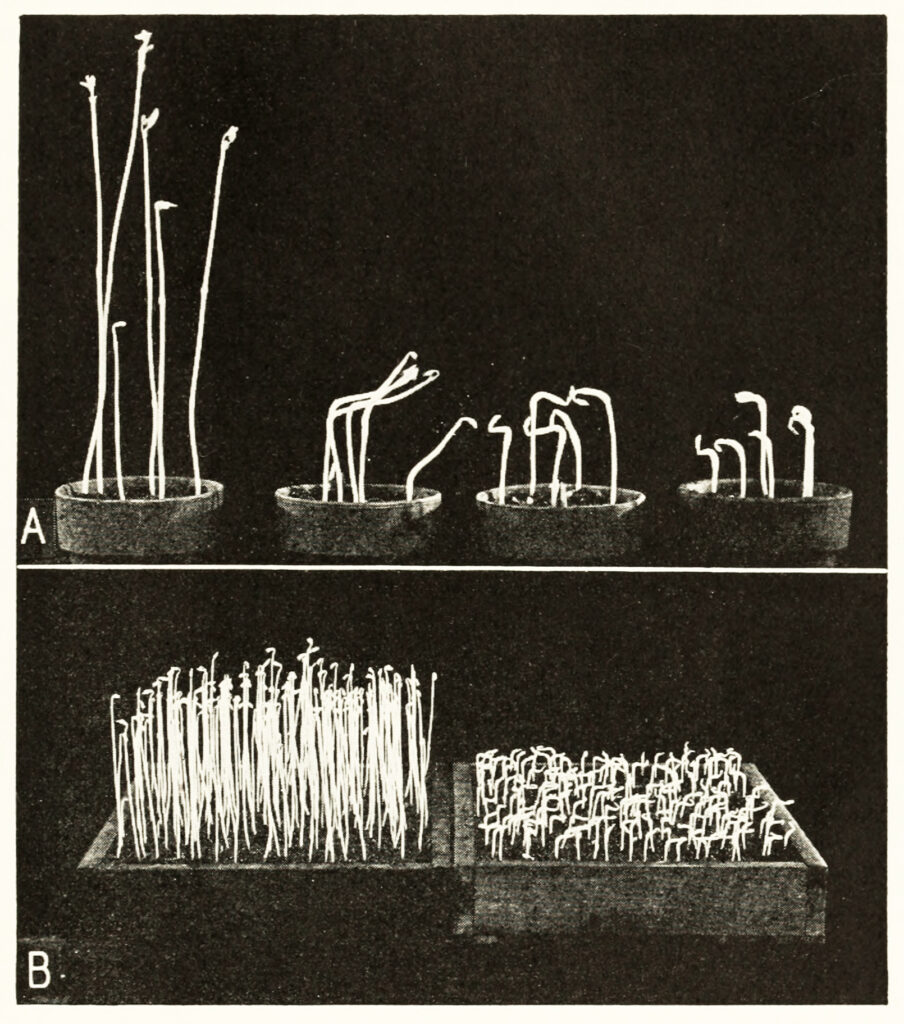

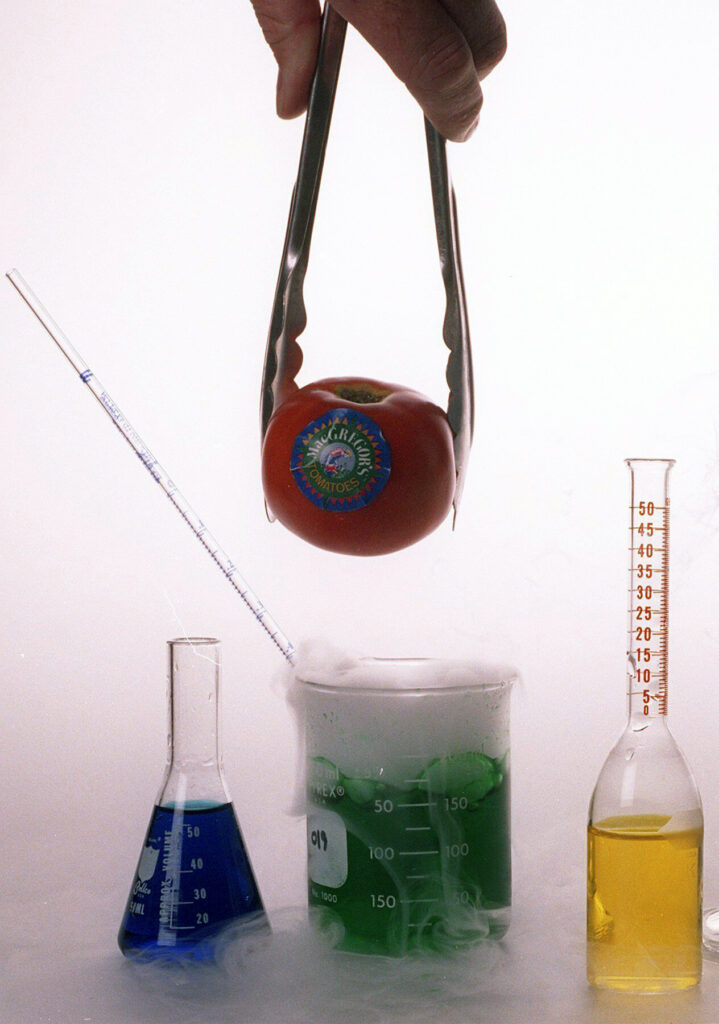

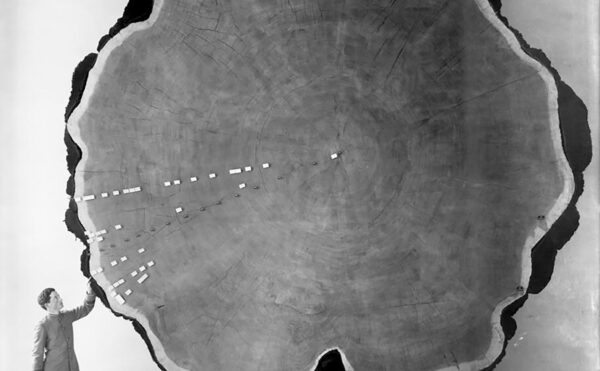

Fruit’s nature makes such a mountain of produce seem nigh impossible. It’s a tricky food to commercialize. Pick it before it’s ripe, and it’s hard, sour, even toxic. But as soon as it becomes palatable, it starts a downslide toward rot. A strawberry spends four weeks developing, but once ripe can soften and form blemishes within hours. A kiwi needs five months to ripen then can turn mushy within days.

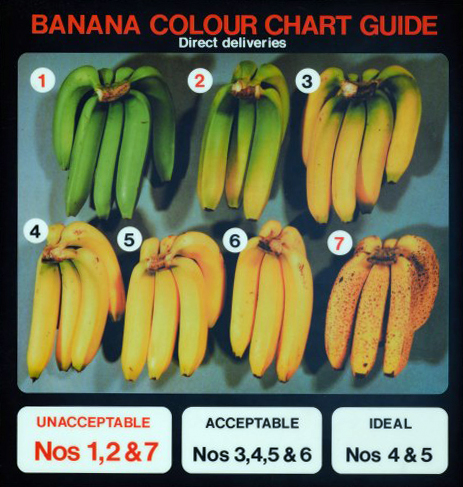

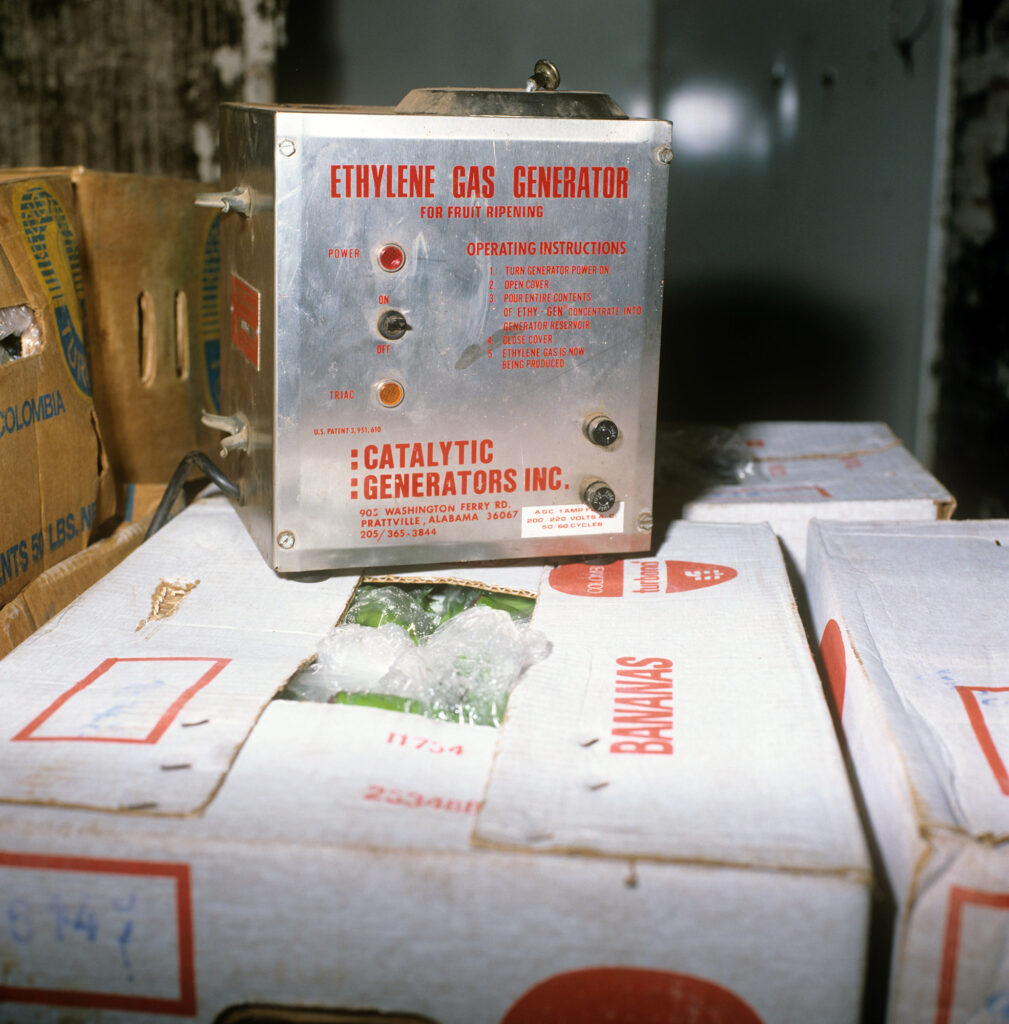

Yet today’s supermarkets greet customers with a riot of ready-to-eat fruit year-round. This is made possible through technologies such as greenhouses, refrigeration, and efficient, long-distance transportation. And there’s another crucial factor at play. For many common fruits, such as apples and bananas, food producers have largely mastered the science of ripeness—how to measure, manipulate, slow down, and speed up the process.

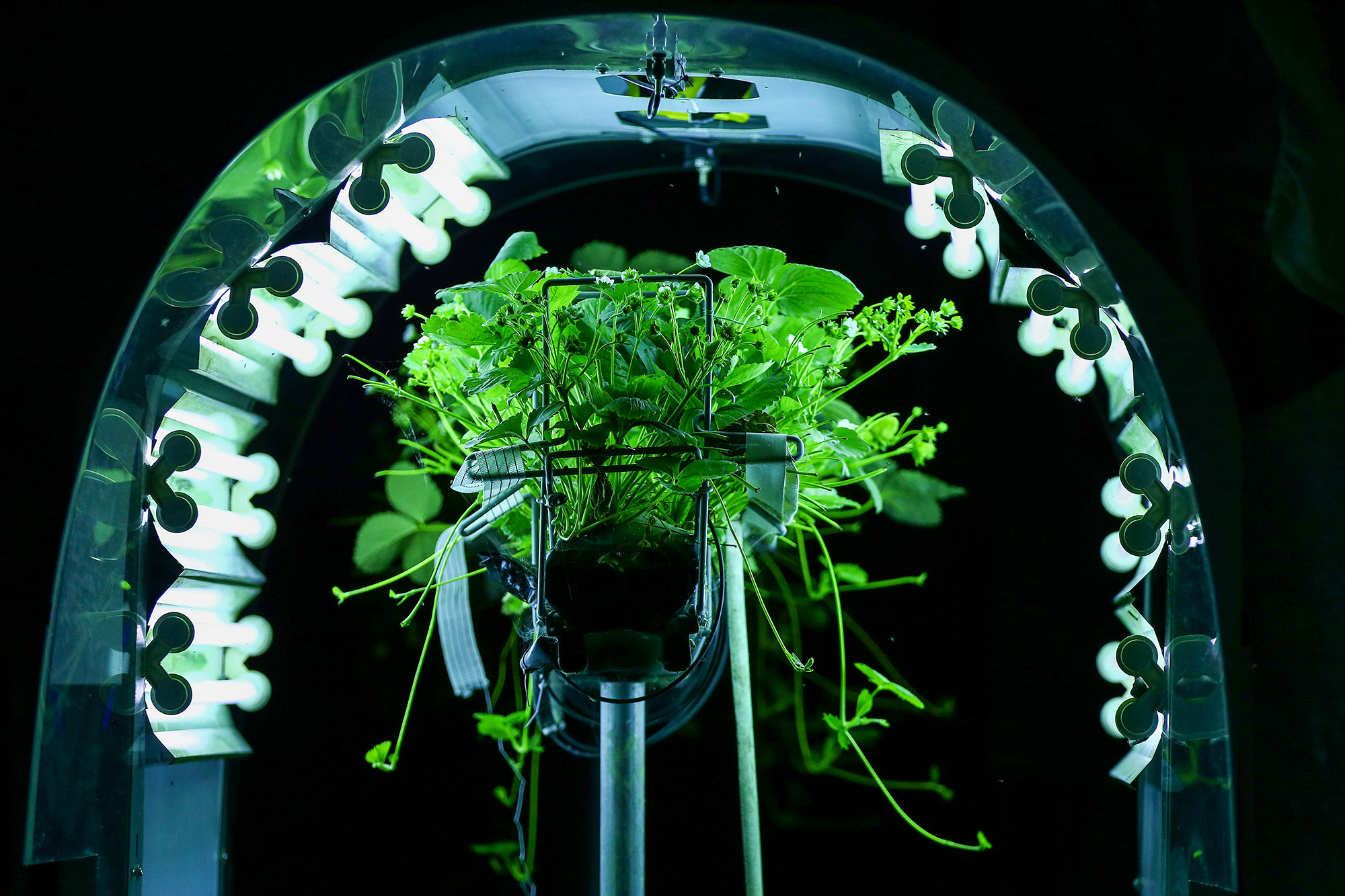

Other fruits, though, have remained stubbornly resistant to scientists’ coaxing. Like strawberries. But how much longer can they hold out?