Until relatively recently, few people took alchemy and alchemists seriously. It was all mumbo jumbo, about as useful as astrology. After all, who could respect anyone who wrote the following: “In our water is required first fire, second the liquor of the vegetable Saturnia, third the bond of mercury. The fire is the mineral Sulfur, and yet it is not properly mineral, nor metallic, but a medium between the mineral and metallic. . . . It is a Chaos or Spirit, because our fiery Dragon, which conquers all things,” etc., etc. This passage was written by a 17th-century alchemist writing under the pseudonym of Eirenaeus Philalethes, who was much admired back in the day, including by Isaac Newton, whose own chemical interests were rediscovered in the 20th century. But what do these words have to do with chemistry? Quite a lot, it turns out.

Today chemistry and the other sciences are described in language that is clear and precise. But a few hundred years ago those who transformed matter for money valued trade secrecy far more than sharing knowledge. Whether making and shaping metals or formulating medicines and pigments, these practitioners put protecting their business first. Secrecy was just as important to the higher-minded tinkerers who sought to understand the transformative powers of nature through the creation of the philosophers’ stone, a mysterious process that turned base metal into gold. The result was a deeply elusive language foreign to modern readers, one that coded chemical processes in allusion and metaphor.

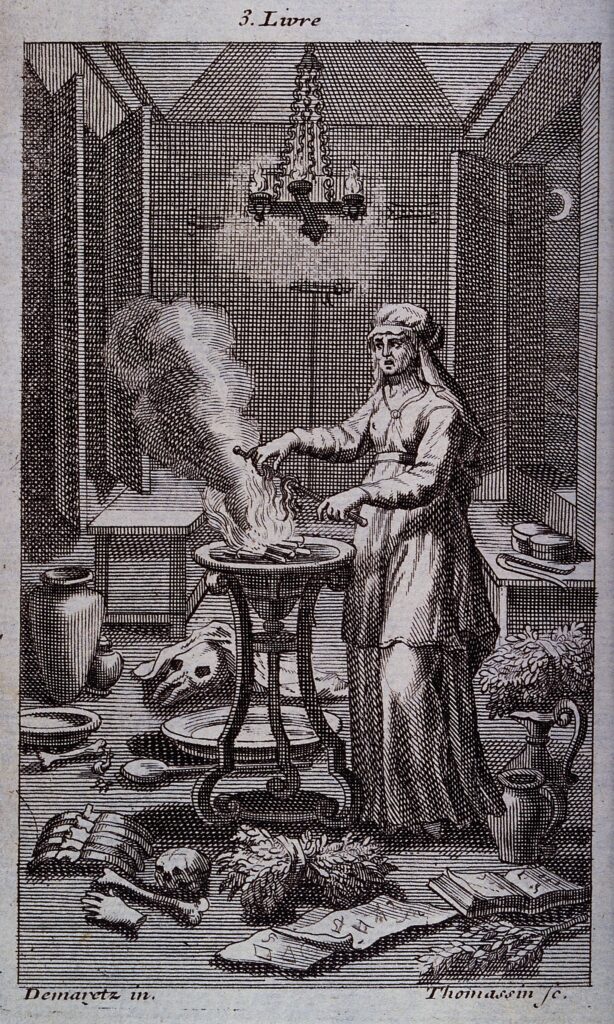

A 16th-century engraving of an alchemist mixing ingredients into a cauldron.

Philalethes’s writing was a tough nut to crack, even for someone like William Newman, a historian of alchemy and early chemistry at Indiana University, Bloomington. Newman worked on Philalethes’s texts on and off from 1978 to 1994. But the key to interpreting Philalethes’s language did not turn up until 1987, when Newman found a letter Philalethes wrote to chemist Robert Boyle that included a description of a chemical process in plain English. Without that letter, Newman remarked, “my head might still be spinning!”

I imagine that our periodic table would be just as strange to the 17th-century alchemists as their words are to us. But understanding the past language of chemistry doesn’t take us all the way to knowing exactly what the alchemists did and how they did it—reading and understanding is not the same as doing. To that end, chemist-historians, such as Lawrence Principe, are now recreating the chemical processes so strangely described by the alchemists. In one video, for instance, Principe makes glass of antimony.

While researching his old alchemists, Newman uncovered another secret: the identity of the man behind the name Philalethes. You can find more about how he did it in our article “Isaac Newton and the American Alchemist.”