Ainissa Ramirez. The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another. MIT Press, 2020. 328 pp. $28.

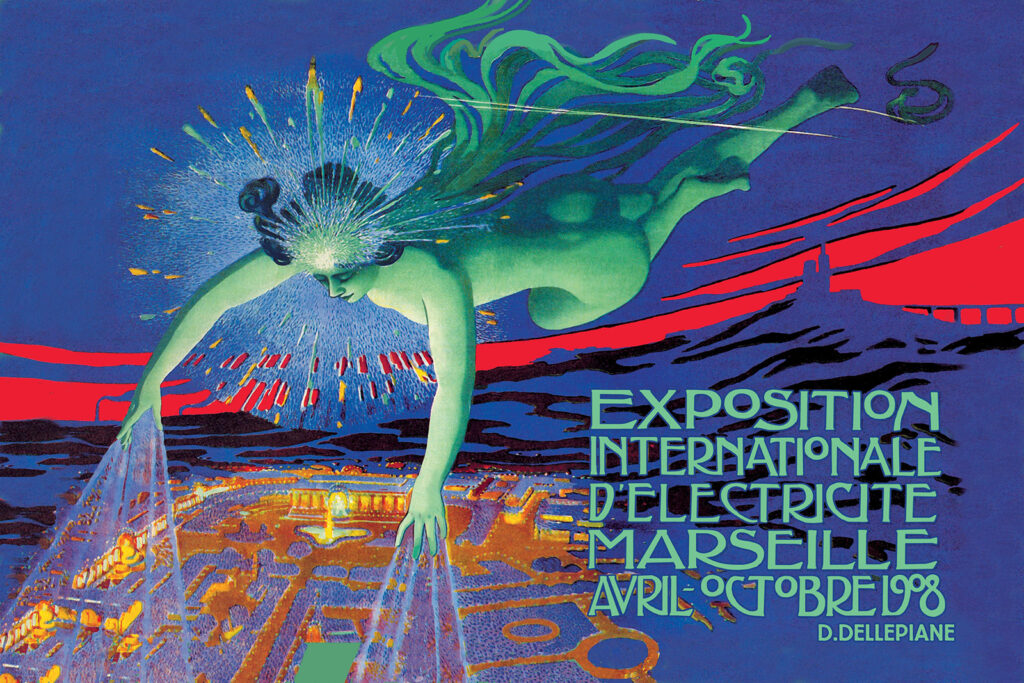

Humans don’t like the dark. The dark is scary and inconvenient when we want to do things, and it eats up a large part of our waking hours each winter. We started using candles 5,000 years ago and have been working to improve our light sources ever since: tallow, beeswax, bayberries, spermaceti, oil lamps, gaslights, arc lamps, incandescent lights, halogen lights, LED lights.

And because we can’t stand the dark, humans are taller.

Let me explain: the human body has two modes, daytime and nighttime. We have a photoreceptor in our eyes that helps our brain tell the difference, and by sending signals to the pineal gland it can stop or start production of melatonin. “During the day,” writes Ainissa Ramirez in The Alchemy of Us, “our temperature, metabolism, and the amount of growth hormone in the body increase. In the evening, they all decrease and we log off.” Candles and oil lamps didn’t mess with those processes, as their dim light was a signal that bedtime was coming. But today we’re surrounded by light that mimics daytime almost too well. The result is bodies in “constant daytime mode,” writes Ramirez, and one of the effects is a body that produces more growth hormone. “Modern humans are taller than their ancestors,” Ramirez writes, referencing sleep scientist Thomas Wehr. “It is partly related to nutrition and other factors, but it is also related to artificial light.

This is one example of how humans, by changing the world around them, also changed themselves. Such stories fascinate Ramirez. A materials scientist by training, she has firsthand knowledge of the difference materials can make in our day-to-day lives. She holds several patents, one of which won her a top 100 young innovators award from MIT Technology Review. She’s also a science advocate who has served as an adviser to the American Film Institute, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, several science museums, and the television series Nova.

And like any renaissance woman she’s an excellent writer. The Alchemy of Us looks at eight innovations (clocks, steel rails, copper communication cables, photographic film, light bulbs, hard disks, scientific glassware, and silicon chips) and shows how they have shaped the human experience. Some of those changes are obvious, and some (such as how our love of light made us taller) are less so.

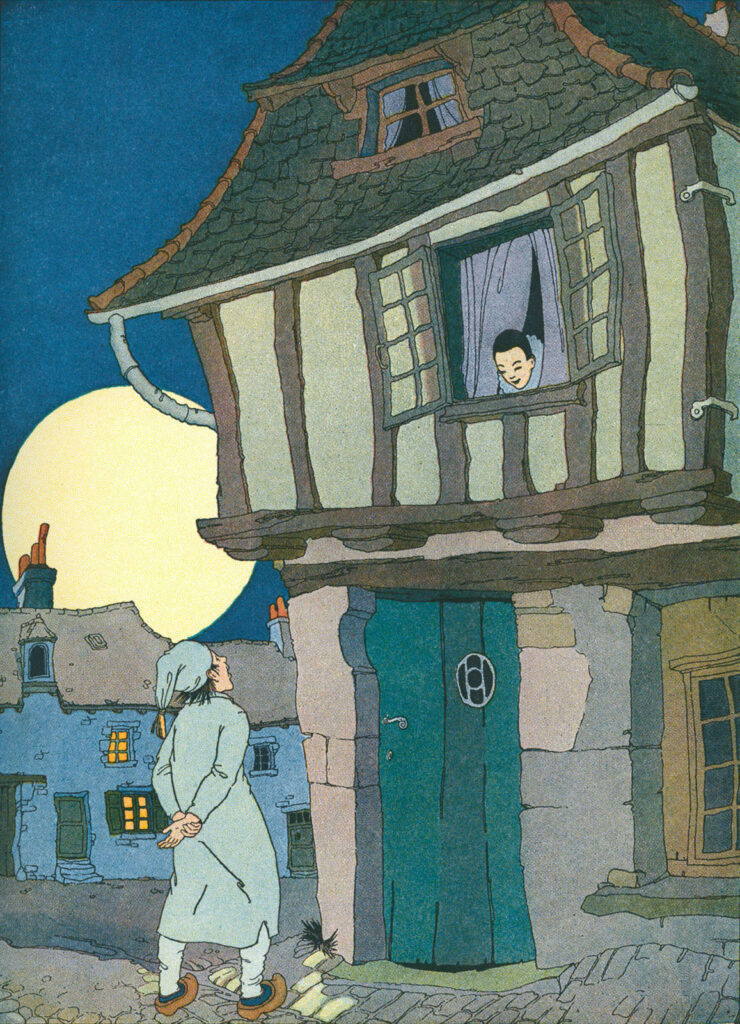

Back to the mysteries of sleep: did you know that in the past humans slept in two chunks? Maybe you’ve seen this phenomenon referred to in old books as first sleep and second sleep: we would go to bed, sleep for a few hours, wake up and putter around for an hour or so (maybe even visit the neighbors), then go back to bed and sleep for another few hours. Humans had followed this pattern for thousands of years, with the earliest recorded mention in Homer’s Odyssey.

Then we invented mechanical clocks. With the advent of accurate timepieces, writes Ramirez, “we became obsessed with time, with being on time, and with not wasting time. As such, it was only a matter of time before this compulsion [affected] how we sleep.” What started out as an instrument to measure our day changed a fundamental bodily function for most people on Earth.

Would our bodies return to biphasic sleep if we let them? Wehr conducted an experiment in which a group of volunteers was plunged into darkness for 14 hours out of every 24 for an entire month. By the fourth week the volunteers had settled into a distinct pattern: sleeping for four hours, waking up for one or two hours, then sleeping for another four hours. If we weren’t such slaves to our own invention, clocks, we might all still sleep like this.

The whole book doesn’t focus on sleep, I promise. The chapter on hard disks examines how we store and share data and opens with a history of recorded music, starting with Edison’s phonograph. Why do we love music so much? No one has found a satisfactory scientific answer. Is it because we like patterns and music is a pattern? Or because music can amplify human emotions, and that resonates with us? We don’t know. But we do know that archaeologists have found bone flutes made 40,000 years ago, when humans should have been concentrating on not being eaten by saber-toothed cats rather than on making music. And as soon as humans learned to “program” machines, about 800 years ago, we were programming them to play music, and only music, for several hundred years. The very first programmable machine was a 9th-century organ powered by water, which turned cylinders studded with raised tabs, a technology you’re probably familiar with from music boxes. So naturally, as soon as we created a machine that could record sounds, music was the sound of choice.

There was a small snag, however: the earliest recording devices captured only a narrow segment of the audible sound spectrum (typically from around 250 hertz to about 2,500 hertz). And “cellos, violins, and guitars produced tones too soft for the early phonograph to pick up,” explains Ramirez, “so louder instruments like pianos, banjoes, xylophones, tubas, trumpets, and trombones became preferred for recordings of music.” Our desire for music changed the kind of music we were listening to: only the music that could be heard on a recording was recorded; the types of music on recordings became popular; because it was popular, more of it got recorded; and so on.

Ramirez’s tales are written for the layperson; so if you’re looking for scientific explanations and diagrams, you’re not going to find them here. You will, however, find a wealth of photos as well as a few nice scientific examples, such as crystal pulling in the hard-disk chapter. Mostly, though, Ramirez concentrates on the stories of the people involved, including those who have traditionally been marginalized—women and people of color. If you’re interested in these kinds of stories, then this is a book you won’t want to miss.