Gene Manis, like many of the young, single, white American men who came to work for the Firestone Plantations Company, looked forward to his initial two-year contract as a junior planter. He had arrived in Monrovia on Christmas Eve in 1939 along with dozens of frozen turkeys destined for the Firestone plantations.

“I am really delighted with the opportunity and experience,” he wrote his mother and sister soon after his arrival in Liberia. “I have some difficulty, even now, making myself realize I am really in Africa, several thousand miles from Montana,” he exclaimed.

The streets of Monrovia, Manis told his family, were “not much more than cow trails and as rough as fourth street used to be” in Hamilton, a town near western Montana’s Bitterroot Mountains, where his interest in science began as a volunteer for a biological field station. But once he neared the plantation on a “very good road” built by Firestone, passed through the security gate, and made his way to Harbel Hills, the recently built new headquarters of plantation management, he could have been in any segregated white resort town in the United States.

On Christmas Day the entire white management staff were treated to a turkey dinner with all the trimmings at the Firestone Overseas Club, reserved for whites only. It featured a large lounge, barroom, juke box with the latest American hits, and a huge “veranda for dancing” that, at that time, “overlooked a native labor camp with mud and thatch houses.” Ping-pong, a nine-hole golf course, tennis courts, and a swimming pool comprised the available recreational activities.

At the Christmas Day festivities, Santa Claus passed out mail and toys to everyone in front of a large Christmas tree improvised from a local conifer species, decorated with tinsel, balls, and lights. Manis had been welcomed to a white Christmas on his first full day as an employee of the Firestone Plantations Company in tropical West Africa.

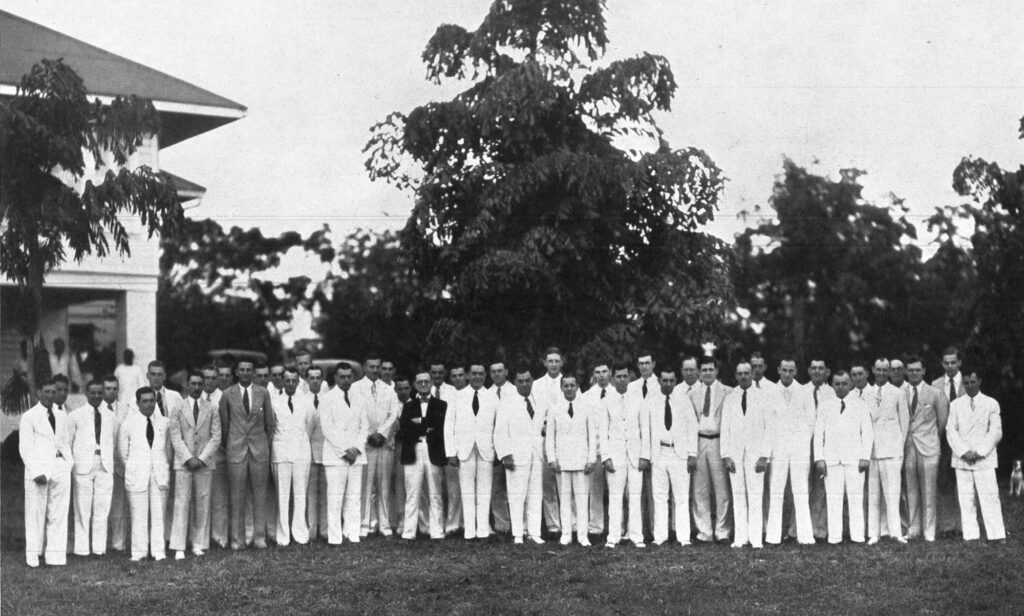

Like many of the American staff, Manis relished the luxury that the privilege of whiteness afforded on the Firestone plantation enclave. The house he lived in and the servants who waited on him were perks he could never afford in the United States as a young agricultural scientist pursuing a PhD in forestry at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Noticeably, most of the white “planters” Firestone hired as divisional superintendents came from Midwestern land-grant colleges located in the United States’ heart of whiteness.

When the Firestone Plantations Company offered Manis an entry-level position at an annual salary of $2,100, when the average income in the United States was $1,368, he took it. But many additional benefits came with the job.

White American staff who were bachelors often shared the typical Firestone bungalow assigned to management, free of charge. The red-brick and metal-roofed bungalows were large, well-furnished homes built on eight-foot pillars and strategically located on hilltops to catch breezes and give views of the plantation. Most white households had anywhere from two to five servants, many of whom were local Bassa people, upon whose customary lands the Firestone concession laid claim.

Manis shared the bungalow with Pat Littell, who had a farm in eastern Oregon and had previously worked on the plantations of United Fruit Company in Panama. Together, the roommates had a cook, steward, gardener, dishwasher, and two car valets working for them. The “boys” are at “our beck and call at all times and expect to be,” Manis told his family.

Out on the divisions where Manis worked, the precise planting, disciplined surveying, and wholesale accounting of life imposed scientific order on what had once been, in the eyes of American industrialists and white scientists, unruly and unproductive nature. Each division, cleared, planted, and tapped by indigenous Liberian labor, was laid out in a specific grid system of 40-acre blocks, separated by lines running east to west, and north to south. Bud-grafted trees were planted in holes 17 feet apart, in straight rows, also 17 feet apart.

The system created a checkerboard pattern of rubber trees, each of which was individually marked and recorded. No variation was permitted, and each step in the process of laying out and planting a division adhered to strict geometric standards and measurements, aided by the precision of a surveyor’s theodolite. “By building a Plantation up through the use of the block system and incorporating a good inspection road system with it, all parts of the Plantation will become easily accessible,” advised a Firestone planting manual. “Field organization and control will be better, and production will be higher,” it affirmed.

Such imposed order did more than improve the control of labor and increase production. It also alleviated white anxieties, born of racist fears. Trepidation of tropical life—of deadly diseases, poisonous snakes, and untrustworthy “natives”—percolated up and animated the writings and conversations of white planters. Like all white planters, Manis oversaw a hierarchically structured Black workforce of two overseers, 14 headmen, and 300 tappers. Order helped to rein in fears of chaos, confusion, and labor unrest that lived just beneath the surface of the idyllic world that Firestone sought to create and project for its white foreign staff.

More than 25,000 indigenous Liberian laborers worked under a foreign white management staff, made up of roughly 160 botanists, foresters, plant pathologists, engineers, chemists, and accountants, almost three-quarters of whom were American. Under the watch of president and CEO Harvey Firestone Jr., who spearheaded the company’s incursion into Liberia in the 1920s, the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company’s plantations exuded whiteness, from the precious latex to the segregated policies and structures of plantation life.

By the end of World War II, W. E. B. Du Bois, who had initially supported Firestone’s Liberia investment, had come to believe the company’s sole object in the country was “to build up a white caste of colonial rulers who have their own housing, their own society, and their own rates of wages.”

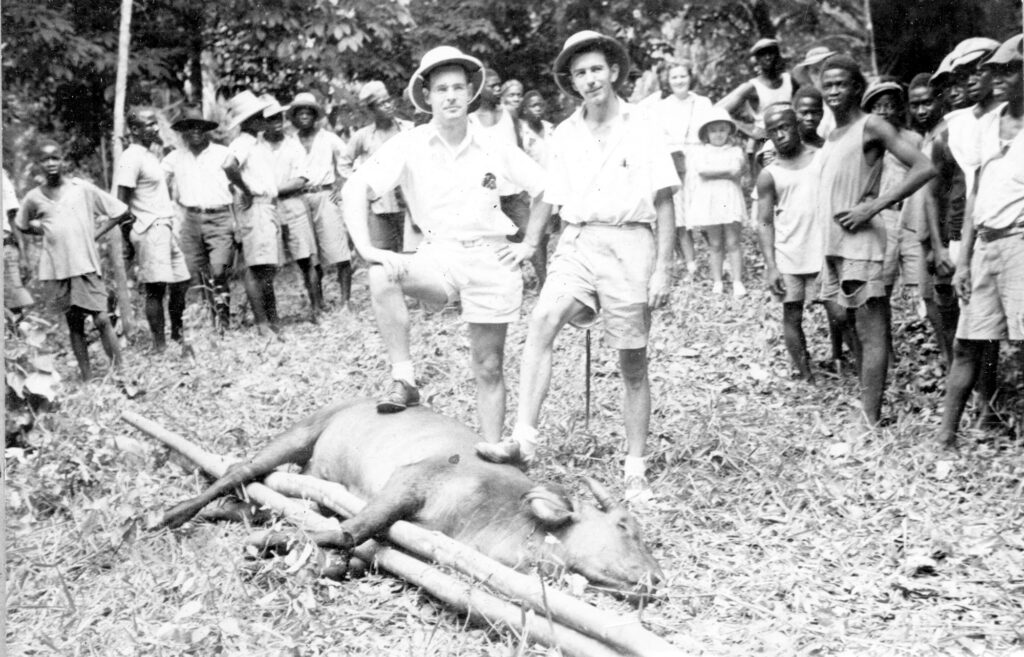

It was a world strictly segregated along racial lines, and the Firestone Overseas Club became its center. From all parts of the plantation, which, by 1947, had expanded to 80,000 acres connected by 195 miles of roads, its white staff and their families would gather there to enjoy in the benefits of plantation life. Saturdays and Sundays were filled with casino nights, dinner dances, golf tournaments, movies, or minstrel shows performed in blackface. American wives socialized over drinks and games, on the tennis court, at the pool, or on the golf course. Picnics at the nearby beach and fishing excursions for barracuda rounded out the range of social activities.

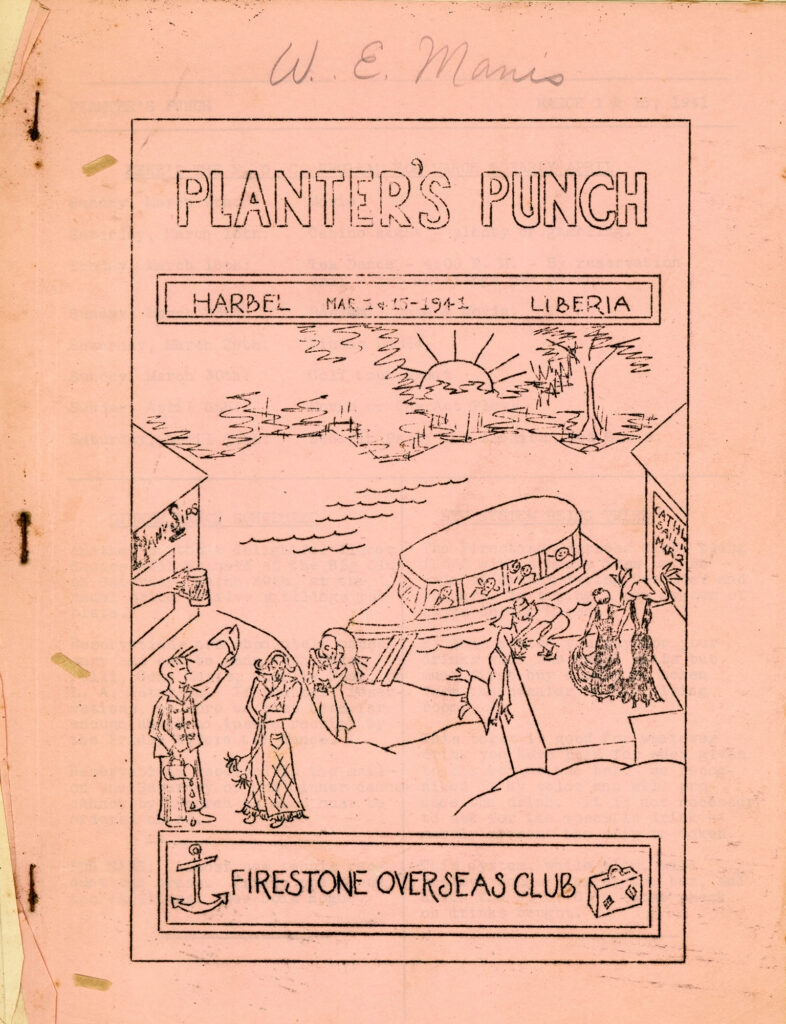

Planter’s Punch, the Firestone Overseas Club’s newsletter, kept the company’s white families abreast of monthly activities and comings and goings. It was filled with racist caricatures and jokes intended to keep their world apart from the worlds of those they depended upon to cook, clean, wash, iron, and shop for them, not to mention harvest latex, upon which their generous salaries and comfortable lives were built and for which they paid no taxes to the Liberian government.

The management staff may have been living in Liberia, but they were not of it, nor did most care to be. “For most of us,” acknowledged Kenneth McIndoe, editor of Planter’s Punch and director of the company’s Botanical Research Laboratory, “knowledge of Liberia is limited to the environs of the Plantation, a passing acquaintance with the outward aspect of Monrovia, and some familiarity with a strip of country bordering the road between the two places.”

White planters such as Gene Manis lived comfortable lives in homes atop the rolling hills of the Firestone plantation complex, situated apart from the villages and lives of the company’s Liberian workers. In the division’s lower-lying areas, too wet for rubber trees, tens of thousands of Liberian tappers, some with their families, inhabited a radically different world. Men from almost every ethnic group and district in Liberia, some hundreds of miles away, came to work on the plantations. Firestone’s plantations were “a veritable tower of Babel-babble,” observed Plenyono Gbe Wolo, the son of a Kru paramount chief and Harvard University’s first Black African graduate.

Kpelle, Bassa, Dan, Mano, and Loma men, among other ethnic affiliations, recruited largely from Liberia’s Central and Western districts, gathered together on the plantations, speaking many different languages and dialects. The ethnic groups recruited for employment matched closely the recommendations that Harvard scientists Richard Strong and George Schwab made to Firestone, based on biomedical and anthropological expeditions they undertook in Liberia in the 1920s with the company’s assistance.

As the Harvard scientists moved through the Liberian interior, their accounts were suffused with judgements and pseudoscientific estimations of who, among Liberia’s ethnic groups, would make the best plantation workers. Consequently, Kpelle men composed the largest ethnic group working as tappers on the main Firestone plantation, and Kpelle, along with Liberian English, became the lingua franca of plantation life.

Tappers were the most essential but least valued workers in Firestone’s operation. Classed as unskilled labor, Firestone tappers earned 18¢ per day until 1950. It was a wage less than half of what unskilled laborers earned across much of colonial West Africa and 1% of what a factory worker earned in Firestone’s Akron plant, where, in 1948, workers averaged $1.73 an hour.

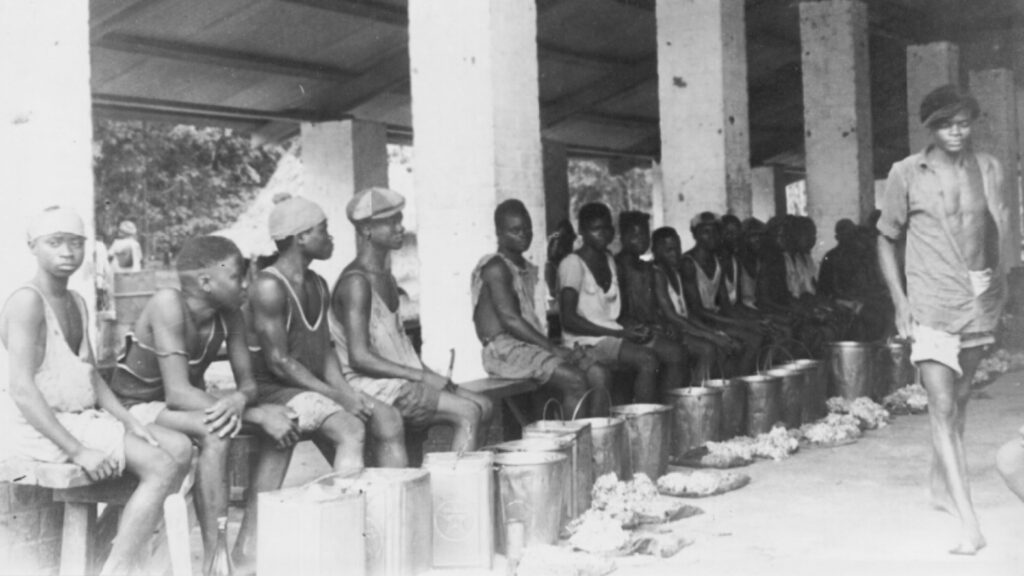

A tapper’s day began well before dawn. At 3:30 a.m., the first muster bell rang. A half hour later, the headman passed through the camp. Gbe, a retired headman interviewed by our research team in 2018, had been responsible for waking up his gang, going “from house to house in the darkness with no light.” “Togbah, you!, Flomo you!, going just like that,” he said. If his entire gang didn’t show, the headman faced a loss in pay.

By 5:00 a.m., all the men had lined up on benches, arranged according to the headman they worked under. Each had his buckets, tapping knife, and ganga bag—a cloth sack to hold tools and coagulated rubber—displayed in front of him. Each tapper placed in his ganga bag a “stout bottle.” Given to him each morning, it contained an ammonia solution, a critical element in aiding the flow of latex from tree to factory. Other essential tools included spouts, glass latex-collection cups, bark gauges, and picule sticks, thick five-foot lengths of bamboo on which tappers balanced full buckets of milk-white latex. “By 5 o’clock, Mr. white man come and check the bucket,” recalled Gwi, who worked for Firestone for 32 years.

Gene Manis was one such “Mr. white man,” arriving at his division camp by 5:00 a.m. to inspect the crew. He noted the number of tappers, made sure each had his complete set of tools, and sent them off promptly by 5:15 a.m. A tapper needed daylight, but tapping as early as possible let more latex flow before the heat of the equatorial sun slowed it. After muster, Manis went back to his bungalow to sleep, waking at 6:30 a.m. to a breakfast cooked by his Liberian chef. While he slept, tappers like Gwi set off in the dark, some walking several miles, to their assigned tile of rubber trees.

Latex—white gold, as it was known in the early 20th century—is an opaque, sticky substance exuded by thousands of flowering plant species. It is a plant’s natural defense against predators. When an insect bites a leaf, a milky liquid containing a mix of defensive agents rises to the leaf surface where, upon contact with air, it coagulates. Rubber, a natural polymer, is one protective substance found in the latex of many plant species. Insects find themselves trapped or their mouth parts mired in the gummy, oozing liquid. Rubber also acts like a bandage, sealing wounds on leaves and stems.

When a stand of rubber trees matured, usually six years after planting, the overseer produced a stand map. He and his crew checked the size of every tree trunk with a metal U-shaped caliper on a long stick and painted a black dot on the tree if its trunk surpassed five inches in diameter. A black dot earmarked a tree for tapping. As crew members called out the status of each tree, the overseer transferred the information onto the stand map in color codes that indicated whether a tree was of tappable size, wind damaged, or not yet ready for tapping. Swamps, streams, buildings, and other obstacles were also noted on the map. In this way, the size, status, and production values of millions of trees could be accounted for.

Firestone invested more in the life of a tree than that of a tapper.

Stand maps also helped lay out the task—or “tile,” as the tappers called it—for each worker. The geometrical renderings of stands within the plantation’s division helped determine the most efficient path for each tapper to follow through the set of trees that fell within his task.

The task structured a tapper’s day. It set the “average quota of work” expected of each man. The task, Firestone Plantations Company manager William Vass advised, was “one of the most important factors in the development and operation of a plantation.”

Tasking had a long history. When cotton was king in the American South, plantation owners used it to organize the work and calculate the value of enslaved people. In the early 20th century the task became a defining element of modern scientific management in industrial factories. In the tire-building rooms of Firestone’s factories, and particularly on its rubber plantations, the task took on ever greater scientific precision.

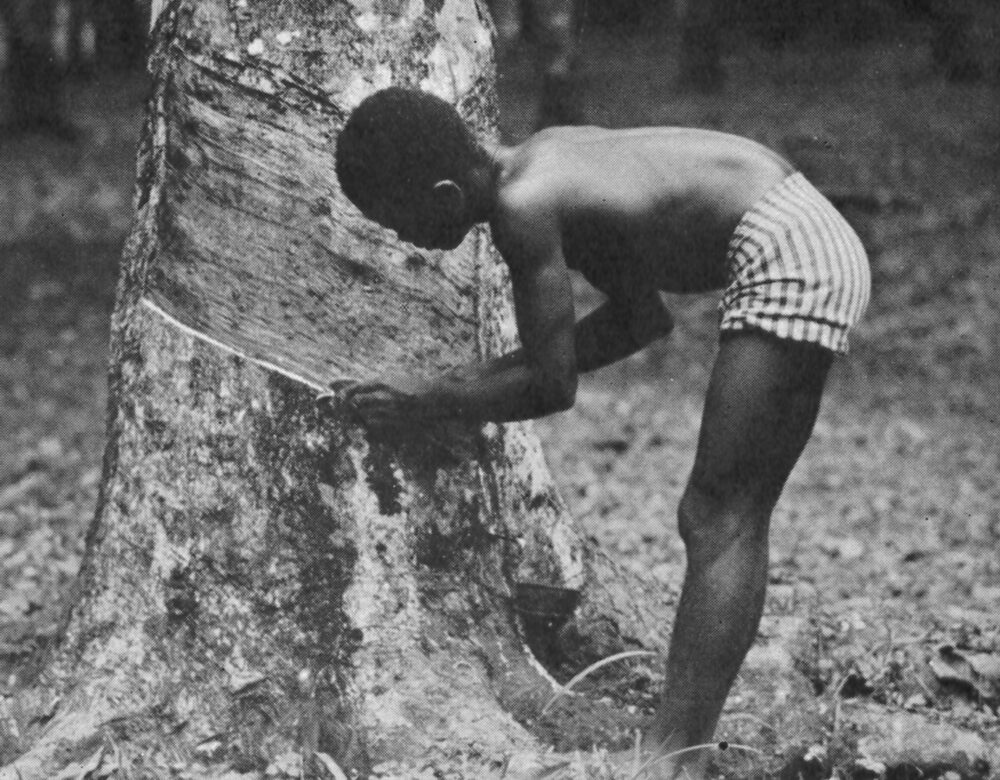

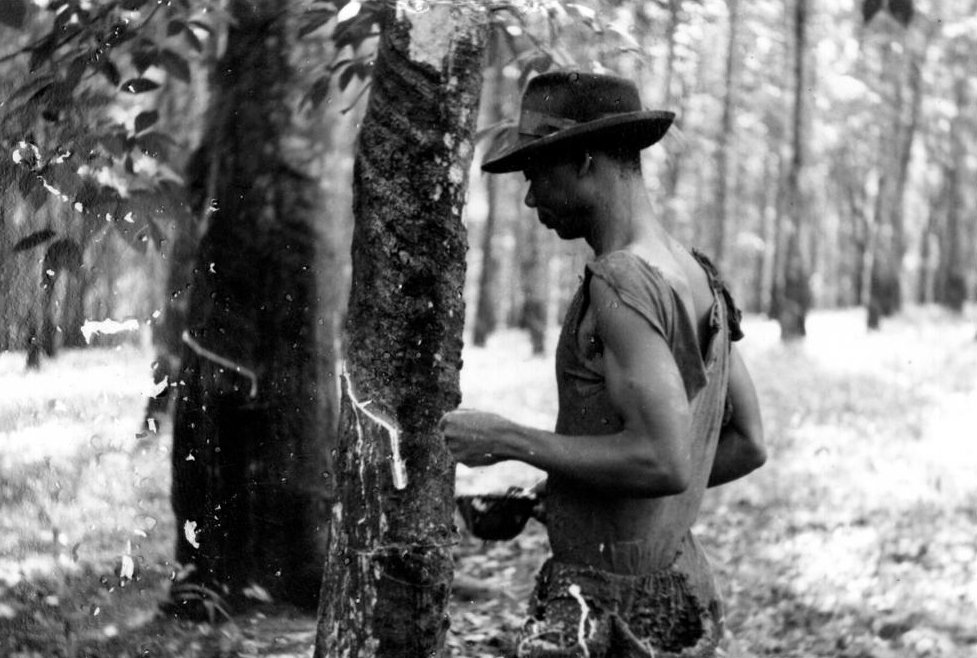

Opening up a stand began by laying out a tapping panel on each tree newly ready for tapping. This commenced an intimate relationship between tapper and tree. A tree tapped with attention and care could yield latex for up to 25 years. A tree’s first tapping panel was always laid on its north side. With utmost skill, the tapper sliced a shallow cut, less than 1⁄16th of an inch wide, into the bark of the tree. The cut, which ran from left to right at an angle of 30 degrees to maximize the number of severed latex vessels, was a controlled wound of the tree.

Cuts mimicked the harm caused by insects and thereby stimulated the plant to release its insect defense, which manifests as latex, the hydrocarbon contained in specialized cells just beneath the outer bark. A cut any wider than 1⁄16th of an inch wasted the tree’s energies regenerating bark. A cut any deeper than one millimeter, the thickness of a dime, risked damaging the tree. If a tapper cut into the cambium, he risked injuring the vital xylem and phloem, the tree’s transport highways that carry water, minerals, and sugars where they are needed. A wound too wide or too deep, and the tapper could shorten the life of the rubber tree. Firestone invested more in the life of a tree than that of a tapper. It didn’t take too many deep wounds before a tapper found himself without a job.

The task set for a tapper in the years Harvey Jr. commanded Firestone’s rubber empire averaged 300 trees per day. Each morning, a tapper cleaned off the thin line of latex—tree lace—that had coagulated and dried in the cut made the previous day. He also cleaned out the cuplump, the latex that had congealed in the collecting cup overnight. Every drop of latex, liquid or coagulum, had value. Every drop, the company laid claim to.

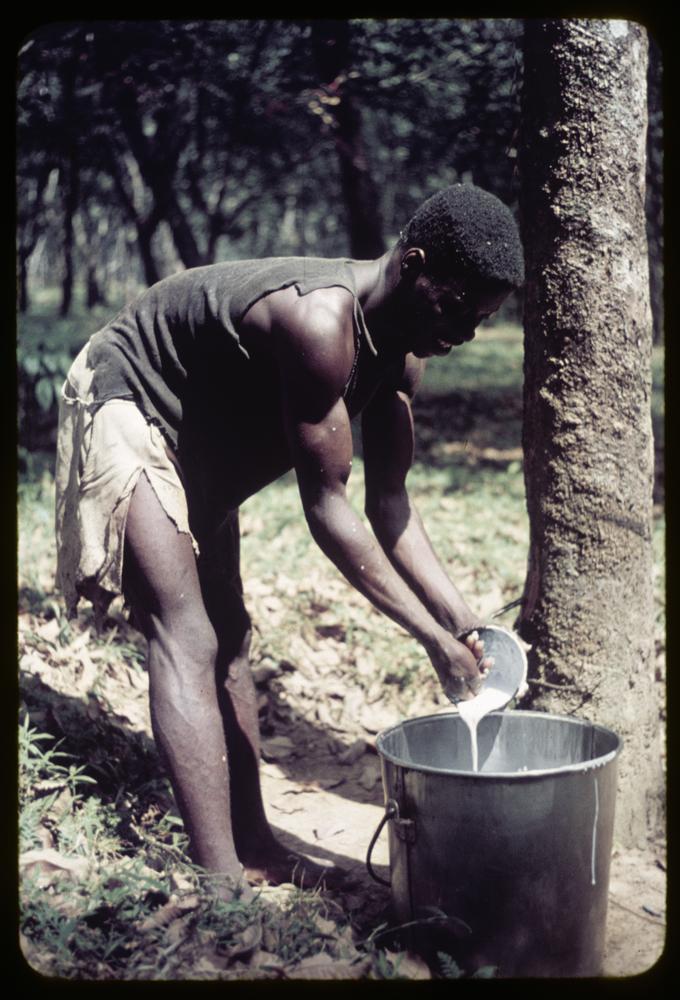

The tapper put the coagulated rubber into the ganga bag, and then opened up a new wound in the tree to start the flow of latex anew. Opening his ammonia bottle, he shook a few drops of the pungent chemical into the collection cup to make sure the “latex don’t sleep.” About 40% of latex is composed of rubber. The rest is a mix of water, sugar, proteins, and salts. When exposed to air, bacteria act on the sugars and proteins, producing acids and putrefying substances that cause the liquid latex to congeal. Keeping latex awake—that is, keeping it in its liquid state—involves ammonia, a powerful base.

Concentrated natural latex, more versatile than crepe or smoked sheet rubber for producing specialized items such as foam mattresses, surgical gloves, and other goods, commanded the highest commodity prices. During World War II, Firestone’s Liberia plantations were the only Allied source of concentrated natural latex. By 1949, when, in just a matter of a decade, Firestone had nearly tripled production on its plantations in response to the war, Liberia supplied 22% of all concentrated natural latex imported into the United States.

If you were a fast tapper, like Gwi, you had time to return to camp to cook and eat a meal before the next bell rang at 10:30 a.m. At the sound of the Bong Bong, a huge gong crafted from a circular saw blade, tappers, with their picule sticks and empty buckets, quickly headed back to their rubber tree stands. Working fast, they went from tree to tree, dumping the milky, ammonia-infused fluid latex into their buckets, wiping each cup out with bare fingers.

Three hundred trees later, each tapper carefully positioned one of his two nearly full six-gallon pails on each end of his picule stick. With the stick and the nearly 100-pound load of fresh latex balanced across his shoulders, the walk from his tile to the collecting station could be body-crushing work. “Oh!” one elder tapper remarked. “Some people can suffer, some people, their tile, they not be near with it,” referring to the distance they had to walk with their latex loads.

Weigh-in began at noon at the division’s collecting station. Hundreds of men, with their pails in hand and ganga bags stuffed with coagulum rubber, waited in line for their turn at the scale, where the amount of latex and coagulum each collected was weighed and carefully recorded. Often, after eight hours of muster, a tapper’s day was not yet done. During the rainy season, tappers would return to their stands to spread fungicide with their fingers across each tree’s wounded bark. They also might return to weed an area around each tree or to open a new stand. To earn the maximum wage rate, a tapper could work an 11-hour day, 26 days or more per month.

Many tappers were not as quick as Gwi. His speed enabled him to earn extra cash, sometimes working two tiles in a day, when a spare tapper was needed. Those who struggled to meet their task faced the harsh consequences of a task system. At first, the headman docked the pay of those who couldn’t keep up. If a tapper continued to falter, he would find himself on the list of spare tappers—reserve laborers who worked irregularly, only when a regular tapper on a headman’s gang didn’t show up for work.

Women might come to the aid of their men if they struggled to meet their task. Key described how she would help her husband collect the cuplump and earthscrap, latex that had leaked onto the ground and solidified. She did so without pay. It was the only way that they, as a family, could ensure her husband’s full wage under the weight of the task system. Male tappers rarely, if ever, spoke of coming to the aid of a fellow member in their gang to achieve his quota. The tapper’s task system incentivized individualism over communitarian values in a male tapper’s world.

Among women who found work on the plantations, a different set of incentives and values prevailed. Firestone began to officially employ women in the 1960s, although in much smaller numbers than men—a 1961 survey counted 17 female workers. Skills women honed cultivating crops assisted them in germination, grafting, and nurturing rubber seedlings in the plantation nurseries. Planting bud-grafted trees also became part of women’s work on the plantations. Group contracts, rather than an individual task system, structured women’s work. The system was more reflective of and reinforced communal labor practices, known as ku among Kpelle people, common to the making of farms in the interior.

The rainy season was planting time on the plantations, as it was up country. Woman planters worked in groups, each group supervised by a headman. Each woman was given four to six bundles of rubber tree seedling, called stumps, with 25 stumps in each bundle, and assigned a cleared area to plant. It was laborious and careful work, supervised by white managers who would suspend or fire someone if their rows were not straight or their trees planted too loosely.

Inexperienced or slow workers could find it challenging to plant all their bundles. Fast planters came to the aid of slower ones, Lomalon recalled. “If you are strong,” she said, “you will leave your friends behind and finish soon. If you are slow, your friends will help you to plant your remaining stumps before you can go home.”

Mutual aid among women laborers ensured the contract was met and helped to nurture tree crops. Retired women workers spoke with pride of cultivating and caring for seedlings now matured into productive trees, much like they would speak of the cash crops grown on their individual farms back home. “Most of the rubber trees you see, my hand work is on many,” Siawa-Geh said, who, like Lomalon, dated her start on the plantation to the early 1960s.

In the transformation of land and ecological relations that built and sustained plantation worlds, Firestone exacerbated certain disease risks and introduced new harms. The making of an industrial landscape was fraught with worker risks. Such occupational hazards, however, posed much less of a concern to the company than did tropical parasites that were a threat to the health of its white staff and to the productive efficiency of labor.

Some risks arising from the industrial ecology of a plantation were biological in origin. The clearing of land, the recruitment of human labor, and the destruction of flora and fauna opened up possibilities for opportunistic insects, along with the parasites they carried, to thrive.

The human-loving black fly, Simulium yahense, was one. The waterways, critical to the plantation’s infrastructure, along with wind breaks and shade furnished by the monoculture rubber forests, offered an ideal habitat for the biting fly. Most active in the morning, when tappers were at work, S. yahense found an abundance of human meals on the plantation. As black flies and people moved to the plantation, they brought along a fellow traveler.

The parasitic worm, Onchocerca volvulus, like its insect vector, flourished in the ecological conditions of the Firestone plantations. Transmitted to its human host via the bite of the black fly, the parasite is one of the leading causes of blindness in sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the tropical world. On the divisions along the Du River, near where Strong’s Harvard expedition originally visited and camped, onchocerciasis, or river blindness, became much more prevalent than elsewhere in Liberia. Sixty years after the first divisions were cleared, the prevalence of Onchocerca infection among male laborers living near the Du River averaged 80%.

Chemicals that proliferated throughout the plantation complex were another health risk. Chemicals such as ammonia were vital to the operation of the plantation. Ammonia, a constant companion in the life of a tapper, was critical to keeping latex in a liquid state. Yet tappers used the chemical without gloves or protective eye gear. It saturated the pores of a tapper’s hands, deadened fingertips, and destroyed nails. Once they filled your ammonia bottle, one tapper recalled, you had to close it quickly or, “it may waste on you and burn your skin.” Some went blind when the corrosive and caustic chemical got into their eyes. “When it flash in your eye, it spoiled it,” Gbe said. “If it is all two of your eyes, it will spoil it.”

Firestone laborers lived and worked in a plantation world teeming with biological, chemical, and physical risks.

Many other hazardous chemicals came onto the Firestone plantations in the postwar years. World War II had spawned an abundance of new chemical compounds. With them came grand schemes for large-scale industrial agriculture, green revolutions, and feeding a hungry world.

Laborers sprayed 2,4,5-T on old rubber trees, then tractors cleared the dead, defoliated vegetation away to make room for new plantings of rubber tree clones. The herbicide had other beneficial effects: it leached into the soil and killed fungi responsible for root rot, a major disease that threatened the health and productivity of Firestone’s rubber trees. But the herbicide contains small amounts of a highly toxic environmental pollutant, dioxin. Scientists paid no attention to the chemical’s possible health effects on workers or on communities living downstream from the Firestone plantations along the Du and Farmington Rivers.

The fight against black thread, a parasitic fungus that inflicted great damage to the bark of rubber trees, also brought an influx of new chemical compounds onto the plantations. The fungus Phytopthora palmivora flourishes best during the rainy season. Its mycelia form vertical black threads on a rubber tree’s tapping panel, coalescing into patches of dark lesions that, if severe, permanently make that bark region untappable. Because black thread proved particularly destructive to Firestone’s prized clone, Bodjong Datar 5, it seriously threatened company profits. The threat prompted extensive research into chemical control.

By the 1960s, a new toxic brew of the herbicide, 2,4-D, which stimulated latex production, and the fungicide, captafol, which killed the dreaded black thread disease, was in widespread use throughout the plantations. Tappers smeared the mixture onto the tapping panel by hand. Captafol, which would later be banned for use in the United States because of its carcinogenic effects, also dripped into the collecting cup that tappers wiped clean with their fingers each day.

Little was “natural” about the production of natural rubber in the postwar years. Firestone laborers lived and worked in a plantation world teeming with biological, chemical, and physical risks. During the war years, lawsuits against the company, brought by Liberian workers injured on the job or by surviving families who had lost a loved one in an industrial accident, became more common.

The family of Solomon Brooklyn Jr. filed a claim in September 1946, asking for $5,000 in damages after an injury to the worker’s foot put him in the Firestone Plantations Hospital where he died of tetanus. The family’s attorney accused Firestone physician Dr. K. H. Franz of “gross negligence and experimentalization of human lives.” Foreign physicians like Franz, “in search of TROPICAL MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCE un-obtainable in the Americas or Europe,” the Liberian lawyer argued, “resort to UNWHOLESOME MEDICAL EXPERIMENTS ON THEIR AFRICAN PATIENTS.” In only loosely suturing the wound and failing to give Brooklyn preventative treatment for tetanus at the time of his admission, Franz had displayed “intentional in-humane treatment” toward an employee of the Firestone Plantations Company, the attorney claimed.

In response to increased pressure by the Liberian government, Firestone had put a worker compensation policy in place the same year Brooklyn died. But its death benefit came nowhere close to the damages that Brooklyn’s family sought.

A worker’s family was entitled to an amount that equaled fourteen hundred times that of his day’s wages. If Brooklyn had been a tapper, Firestone would have paid out $252 ($3,348 in today’s dollars), provided the cause of death was not worker negligence. Had Brooklyn lived, but lost use of his foot, he would have received $126. A hand was worth 700 times more than a worker’s wages; an eye, 640 times more. Partial loss of a tapper’s sight was valued at no less than $28 and no more than $86.

In the calculus of worker’s compensation, Firestone disclosed the value it placed on the lives of Black laborers in the Jim Crow enclave it had imported to Liberia. It was a valuation founded upon structures of racial capitalism rooted in the violent and bloody soil of plantation slavery.

Firestone touted its Liberia plantations as an exemplar of modern industry and progress, buttressed by the transformative power and humanitarian benefits of American science and medicine. But in its segregated and unequal treatment of white and Black workers, support of racist science and medicine, and extraction and export of wealth amassed from confiscated lands, Firestone shared more in common with past plantation worlds than it stood apart from them.

©2023 Gregg Mitman. This excerpt originally appeared in Empire of Rubber: Firestone’s Scramble for Land and Power in Liberia, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission. The author has used pseudonyms to protect the identities of Firestone workers interviewed.