For most of history, humankind has been terrified of eclipses. The Vikings, the Maya, the ancient Chinese—they all trembled in fear, and understandably so. Imagine being an average farmer or herder and seeing the sun blotted from the sky with no warning. Terrifying stuff.

Given this fear, cultures around the world often linked natural disasters and untimely deaths to eclipses. Famous deaths that have been linked to eclipses include Charlemagne and his heir, Louis the Pious; the Prophet Muhammad’s son Ibrahim; and Jesus of Nazareth when the land was cast into darkness during his crucifixion.

Nowadays we’re likely to dismiss such links as superstition. Among astronomy buffs, however, the August 1868 solar eclipse in Southeast Asia is known as the King of Siam’s eclipse for its role in the death of King Mongkut, Rama IV, best known in the West as a character in the musical The King and I. But if the eclipse did lead to Mongkut’s demise, his deep love for astronomy helped save the kingdom itself from destruction.

Mongkut was born in Siam—modern-day Thailand—in 1804. The young prince was groomed for the throne from an early age and by all accounts enjoyed the royal life. Then, he gave it up—at least temporarily. At age 19, he entered a Buddhist monastery. Joining a monastery was a common step for young men, a way to teach them humility and discipline, comparable to modern princes attending military school. His sojourn as a monk seemed destined to be short-lived, however, when his father fell ill and died within a month of his ordination. Mongkut fully expected to assume the throne.

Except, life swerved on him. After his father’s death, royal advisors passed over young Mongkut in favor of his 36-year-old half-brother. Perhaps to avoid an ugly dynastic fight, Mongkut chose to remain a monk and maintain the austere lifestyle—begging for food, renouncing worldly possessions, avoiding contact with women. Quite a letdown for a prince.

Still, he made the most of his time. He led a series of reforms in Siam’s monastic orders, instilling discipline and tightening standards for conduct. He began studying European languages and cultures as well, partially in response to Great Britain and France’s growing aggression in Southeast Asia. Previous regimes had largely rebuffed European commercial interests in the country, but after the British defeat of Burma in 1826, and later China in 1842, Siamese rulers realized they could no longer ignore the West. To resist encroachment, Mongkut would have to understand the colonizers’ worldview. Among other things, he began studying Western geography and sciences, and was especially drawn to astronomy.

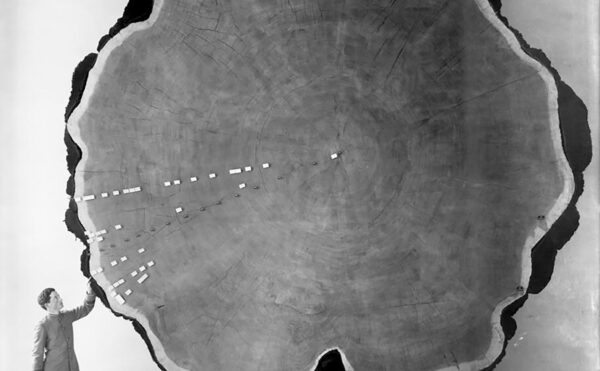

As an ancient kingdom, Siam had its own cosmology, including unique constellations. (Parts of what Westerners call Ursa Major, the great bear, they called crocodile stars.) The Siamese also used planets and stars to cast horoscopes, plot out their calendar, and determine the dates for religious holidays.

Mongkut, however, realized the monks in charge of the Siamese calendar were using outdated techniques and equipment, which led to poor and inaccurate results. Christian Europeans had experienced similar problems before reforming their calendars in the late 1500s. So Mongkut spearheaded a comparable reform. He began reading up on Western methods of tracking the sun and stars and eventually brought Siam’s Buddhist calendar up to date, rendering it more accurate and stable.

All the while, Mongkut waited to become king—although at several points his ascent seemed unlikely due to poor health. He lost all his teeth and at one point suffered a small stroke. Photographs from those years show him gaunt and white-haired, the right side of his face drooping from the stroke.

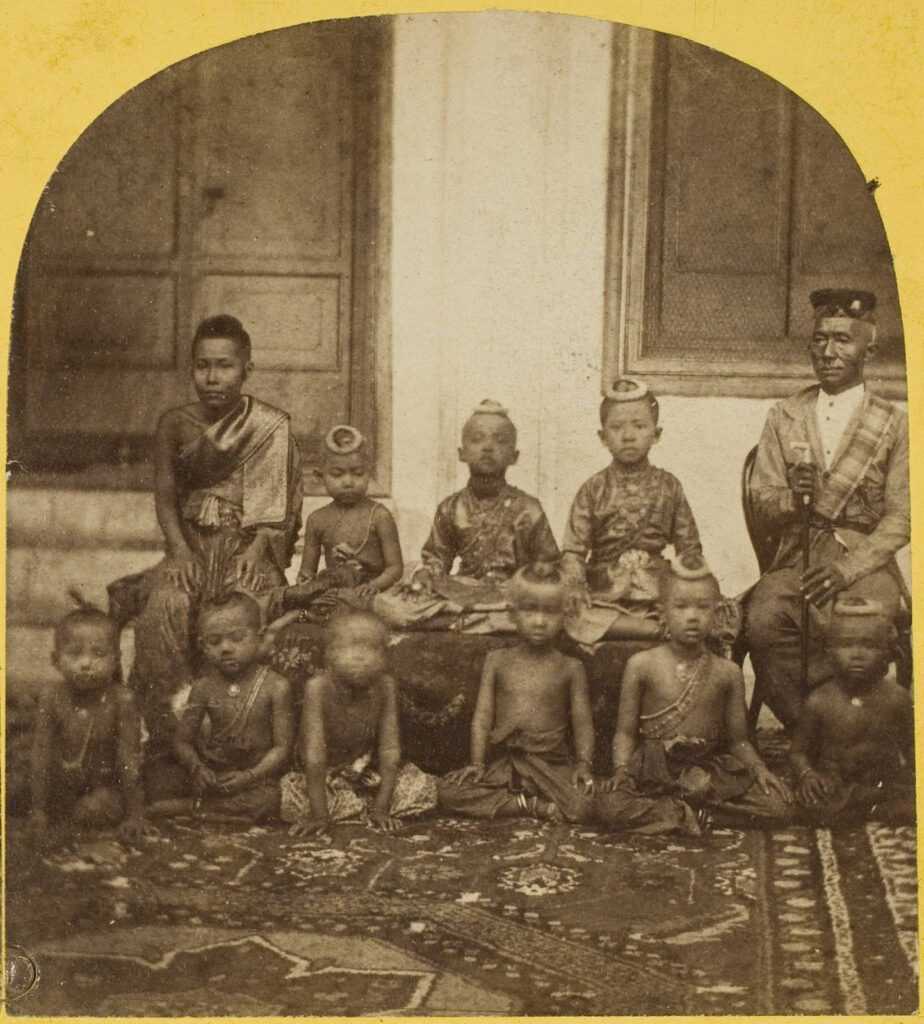

Finally, in 1851, his half-brother died. After 27 years as a monk, Mongkut ascended the throne at age 46. Mongkut married many times and eventually fathered 80 children beyond two he had sired as a teenager. The new king faced the serious task of keeping Siam independent from the British and French colonialists who were closing in on all sides, eager to carve the country up. He would have to tread carefully.

Keeping his country independent would also require maintaining a strong home front, a challenge best highlighted by his dilemma regarding his children’s education. Many Westerners are dimly aware of this challenge due to the musical The King and I, whose plot revolves around the clash of two cultures: Mongkut wants to find a tutor to teach his children Western ways yet remains suspicious of most Westerners (especially missionaries), who he fears will convert his children to Christianity on the sly and undermine the kingdom. He eventually selects Anna Leonowens, a young widow from India who ran a school in Singapore, whose charm and influence help civilize him.

Unfortunately, that depiction has skewed how most Westerners view Mongkut, who actually enjoyed friendships with several missionaries. And while the king certainly put great value in preserving traditional Siamese ways, he knew far more about certain aspects of Western culture, especially science, than most colonialists. Indeed, the film’s depiction of a vain and brutish king was deemed so offensive that it’s still banned in Thailand today.

The depiction of Leonowens was also ill-informed. In reality, she was most likely the daughter of a British soldier and an Anglo-Indian woman; she concealed her ethnicity throughout her life, probably to avoid prejudice. (Leonowens’s heritage was unknown when the musical was written.) Nevertheless, perhaps because she had a foot in both worlds, Asian and European, the real-life Anna proved a fine tutor, teaching Rama’s children Western ways without undermining their traditional values.

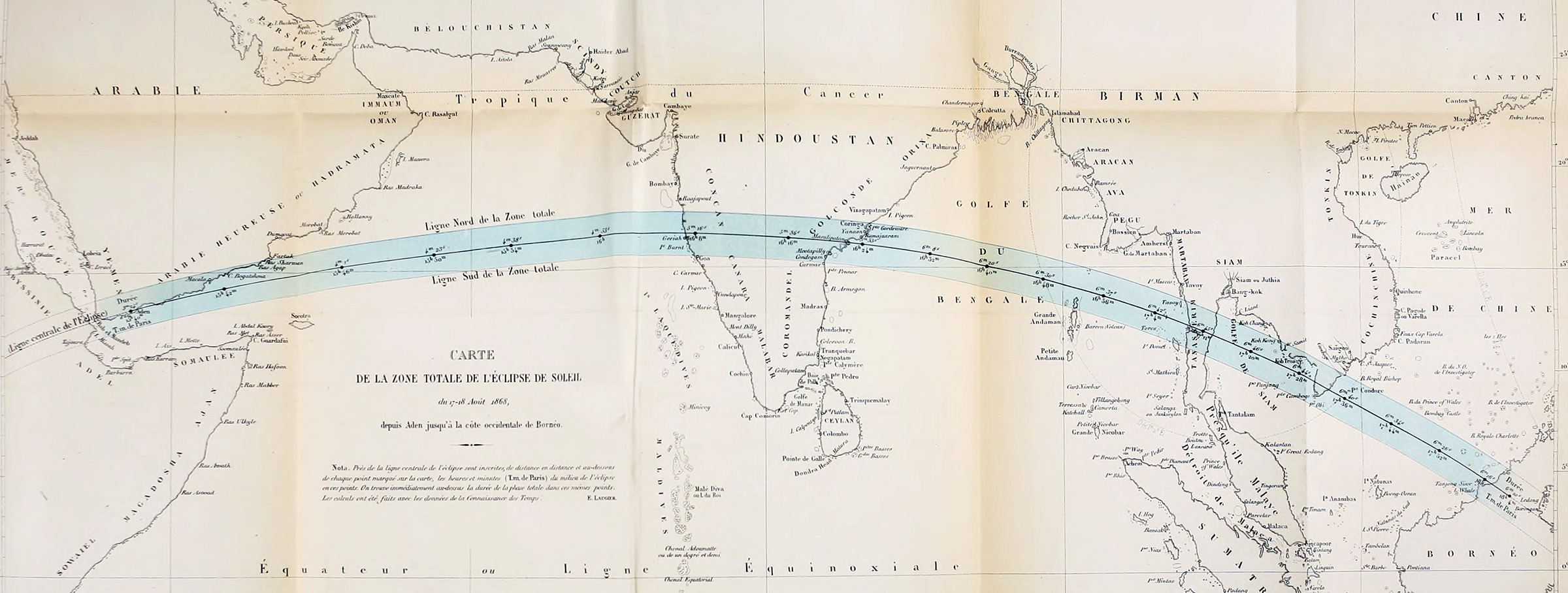

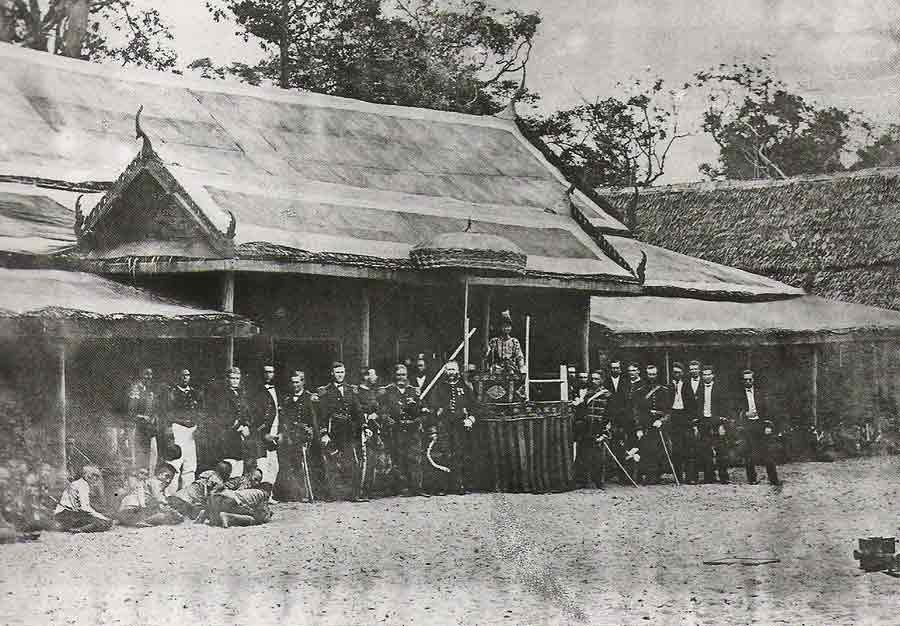

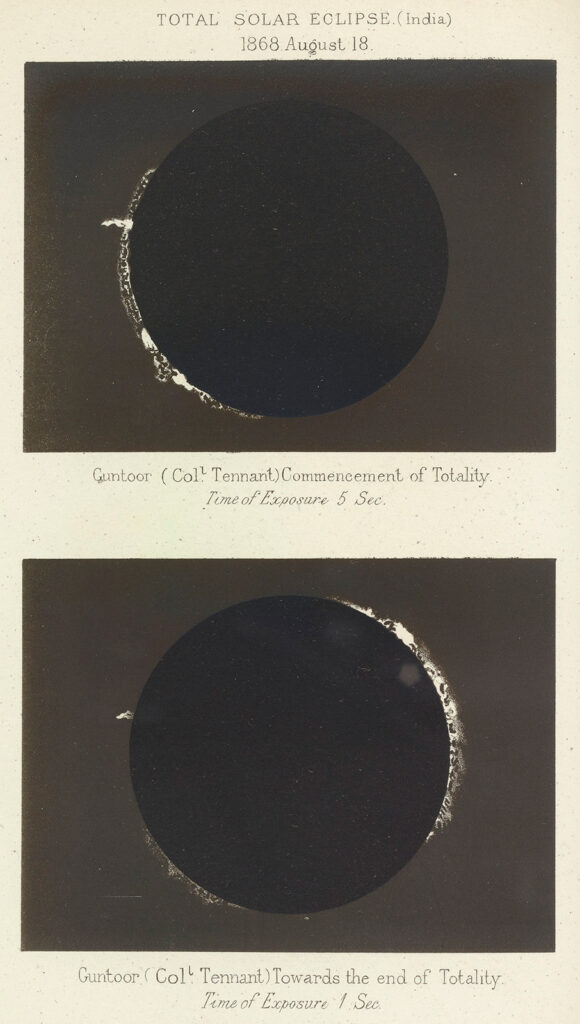

The weight of Mongkut’s royal duties could not stifle his interest in astronomy. When British officials visited his court in the mid-1850s, he quizzed them on the discovery of Neptune. Even more exciting, in the mid-1860s, Mongkut realized his kingdom would soon become the center of the astronomical world: on August 18, 1868, a solar eclipse would streak right across it.

Hearkening back to his days as a monk, Mongkut set out to calculate the exact time the eclipse would occur and how long the period of total darkness (the totality) would last in Siam. Such calculations were intricate business at the time, requiring demanding computations about the moon’s and sun’s precise speeds and paths through the sky. There were dozens of variables to juggle, and even a tiny mistake could throw off the entire result.