It was late August 1905 in the small village of Commugny, Switzerland, and three coffins stood open to the air. The mother’s was the largest, adult-sized; a smaller casket held her four-year-old daughter, Rose. In the smallest coffin lay her two-year-old daughter, Blanche.

Before the coffins stood Jean Lanfray, a burly, French-speaking laborer. Facing the bodies of his family, he wept, insisting he didn’t remember shooting the three. “Please tell me I haven’t done this,” he wailed. “I loved my family and children so much!”

Lanfray had drunk his way through the previous day, beginning near dawn with a shot of absinthe diluted in water. A second absinthe shot soon followed. At lunch and during his afternoon break from work at a nearby vineyard, he downed six glasses of strong wine. He drank another glass before leaving work. Heading home, Lanfray stopped at a café and drank black coffee with brandy. Back home Lanfray finished a liter of wine as his wife watched in disgust. She called him lazy. He told her to shut up. She told him to make her. He took his loaded rifle from the wall and shot her through the forehead. When his daughter Rose came to investigate, he shot her too. Then he went into the next room, walked to the crib of his other daughter, Blanche, and shot her.

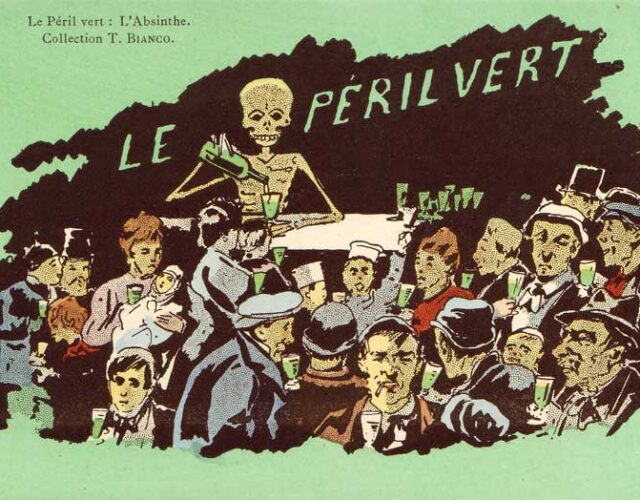

From this domestic tragedy the people of Commugny drew one inescapable conclusion: the absinthe made him do it. Anti-absinthe sentiment had been bubbling throughout Europe, and in Switzerland it boiled over. “Absinthe,” Commugny’s mayor publicly declared, “is the principal cause of a series of bloody crimes in our country.” A petition to outlaw the drink gathered 82,000 signatures in just a few days.

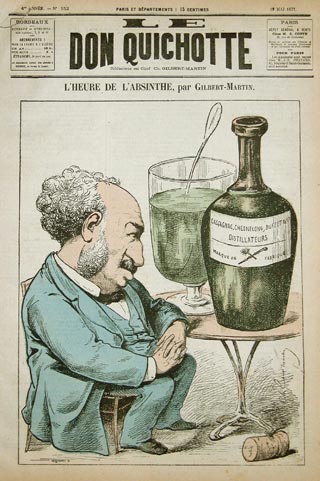

The Hour of Absinthe, by Gilbert Martin. Published in the satirical journal Don Quichotte.

The press seized on Lanfray’s story, dubbing it “the absinthe murder.” For members of the anti-absinthe movement (including many newspaper editors), two glasses of pale-green liquid explained why a family lay dead. Prohibitionists could not have imagined a more potent metaphor for social decay. La Gazette de Lausanne, a French-language Swiss newspaper, called it “the premiere cause of bloodthirsty crime in this century.”

At his trial the following February, Lanfray’s lawyers declared him a classic case of absinthe madness—a medically ill-defined affliction, but one that captured the public imagination. The lawyers called to the stand Albert Mahaim, a leading Swiss psychiatrist. He had examined the defendant and declared confidently that only sustained, daily corruption by that foul drink could have given him “the ferociousness of temper and blind rages that made him shoot his wife for nothing and his two poor children, whom he loved.” The prosecution countered that his absinthe consumption was dwarfed by his prodigious intake of other alcohol.

The trial lasted a single day. Found guilty on four counts of murder—his wife, an examination revealed, had been pregnant with a son—Lanfray hanged himself in prison three days later.

The murders energized prohibitionists—the drink became a Swiss national concern. The canton of Vaud (containing Commugny) banned it less than a month after Lanfray’s death. The canton of Geneva, reacting to its own “absinthe murder,” followed suit. In 1910 Switzerland declared absinthe illegal. Belgium had banned it in 1905 and the Netherlands in 1910. In 1912 the U.S. Pure Food Board imposed a ban, calling absinthe “one of the worst enemies of man, and if we can keep the people of the United States from becoming slaves to this demon, we will do it.” By 1915 the Green Fairy (la fée verte, as the absintheurs called it) had been exiled even from France, long the center of absinthe subculture.

While temperance movements had blossomed worldwide in the late 1800s and early 1900s, never before had an individual alcoholic drink been targeted. Yet by World War I, throughout the world a combination of economic interests, dubious science, and a fear of social change—and the tabloid stories that used murder to inflame readers’ imaginations—had turned the Green Fairy into the Green Demon.

The press seized on Lanfray’s story, dubbing it “the absinthe murder.”

Absinthe was not always the devil in a bottle. The French name derives from the Greek absinthion, which the Greeks used not as an intoxicant but as a medicine. Typically made by soaking wormwood leaves (Artemisia absinthium) in wine or spirits, this ancient absinthe supposedly aided childbirth. Hippocrates, often considered the first physician, prescribed it for menstrual pain, jaundice, anemia, and rheumatism. Roman scholar Pliny the Elder describes chariot-race champions drinking absinthium, its taste reminding them that glory has its bitter side—a sentiment wholeheartedly embraced by later enthusiasts.

Throughout the centuries wormwood remained a folk medicine. Galen, a physician during the second century CE, suggested it for stomach relaxation and as a remedy for swooning. British herbalist John Gerard wrote in 1597, “Wormewood voideth away the wormes of the guts.” This evocative connection helped solidify Artemisia absinthium’s common English name. When the bubonic plague returned to England in the 17th and 18th centuries, many people burned wormwood to fumigate infected houses.

For centuries wormwood drinks remained primarily medicinal. (More recreational concoctions occasionally appeared, such as wormwood wine and crème d’absinthe.) Then in 1830 France conquered Algeria, beginning its expansion into North Africa. As local resistance grew, the French army sent reinforcements, amounting to 100,000 soldiers by 1840. The heat and bad water took their toll, with fever tearing through the ranks. The men received wormwood to quell fevers, prevent dysentery, and ward off insects. They took to spiking their wine with it, which cut the bitterness and provided an alcoholic punch. Returning to France, they brought with them a taste for the drink, dubbing it “une verte” for its distinctive green color. And soon civilians, eager to align themselves with their newly victorious empire, began asking for “a green.”

At first absinthe remained a middle- and upper-class indulgence. But it had an exotic appeal; legends grew about its long history and supposedly hallucinogenic effects. As prosperity spread, more people partook of l’heure verte, the “green hour” of early evening when the unique smell of absinthe wafted through the air. Savvy customers realized that with its high proof, absinthe delivered more force for the franc. Diluted with water (virtually no one could drink it straight), it went even further. By 1849 the 26 French absinthe distilleries were producing some 10 million liters, a small fraction of the prodigious amount of alcohol consumed in France.

A minority of artists and poets evangelized loudly in favor of the Green Fairy. Absinthe became synonymous with mad genius as literary luminaries like Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud sang its praises. In 1859 Edouard Manet painted The Absinthe Drinker, a realistic portrait of a street bum clad in rags and wearing a gnarled top hat, his left foot thrust forward in defiant insouciance. Next to him sits an emerald glass.

Manet’s painting was rejected from that year’s Salon of Paris. It caused his mentor, Thomas Couture, to shake his head: “My poor friend, you are the absinthe drinker. It is you who have lost your moral faculty.” Manet had dared to portray absinthe intoxication realistically; indeed, his painting lent its subject an insolent grandeur. His new mentor, poet Charles Baudelaire, had declared, “One must be drunk always. . . . With wine, poetry, or with virtue, your choice. But intoxicate yourself.” The absintheurs idealized intoxication. Polite society did not.

The absinthe mythology— of the Green Fairy of liberation, of altered perceptions and unveiled meanings—appealed to creative libertines around the world. Vincent van Gogh was a convert, as was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Playwright Alfred Jarry sought his destruction in absinthe; Pablo Picasso dabbled in it for a time, painting The Absinthe Drinker and the cubist breakthrough The Glass of Absinthe, but never gave himself over to it. Oscar Wilde declared, “A glass of absinthe is as poetical as anything in the world. What difference is there between a glass of absinthe and a sunset?”

Often reproduced, the Absinthe Blanqui poster is an art-nouveau image inspired by the cultural trend of orientalism at the time.

Even Ernest Hemingway, not especially known for decadence or dandyism, embraced absinthe. He called it “opaque, bitter, tongue-numbing, brain-warming, stomach-warming, idea-changing liquid alchemy,” saying, “It’s supposed to rot your brain out, but I don’t believe it. It only changes the ideas.” Hemingway succinctly captured the danger and allure of the pale-green drink. To enthusiasts it promised new ideas. To the unconverted it symbolized madness—“une correspondance pour Charenton,” a ticket to Charenton, the insane asylum outside Paris.

The most systematic studies of absinthe toxicity took place at another Paris asylum, under the supervision of a psychiatrist seeking to prove that absinthe did indeed “rot your brain out.” Valentin Magnan, an influential and well-respected psychiatrist, was appointed physician-in-chief of France’s main asylum, Sainte-Anne, in 1867 and thus became the national authority on mental illness. He diagnosed a steady decline in French culture—a not uncommon belief.

While Magnan ignored the wilder, medically unsupportable claims of absinthe’s sinister effects, he shared the general concern about the fitness of the French population. Like many nationalists of the time he believed in a “French race”: the concept of “degeneration” had much currency among public officials of the time, as ideas about heredity filtered into public discussion. Claims of degeneration—of a once-great nation now in decline—spurred action and anger, though such claims were often scientifically and statistically confused. Those who saw the French race collapsing, Magnan among them, could point to increasing instances of diagnosed insanity—most likely the effect of better diagnostic techniques—and to the strain of modern industrial life on already at-risk psyches. They could also point to lower birth rates—now seen as a nearly inevitable consequence of higher living standards and greater female education. Given the massive social and industrial changes of the 19th century, many unsurprisingly looked for culprits. And for Magnan, who found signs of national collapse in his asylum, absinthe became the villain responsible for an entire host of social ills.

In response Magnan sought to define “absinthism” as distinct from alcoholism. In 1869 he published results of an experiment designed to do just that. He placed one guinea pig in a glass case with a saucer of pure alcohol. A second guinea pig got its own case and a saucer of wormwood oil. Two other cases contained a cat and a rabbit, both with saucers of wormwood oil. As Magnan watched, the three animals inhaling wormwood fumes grew excited and then fell into seizures. The alcohol-breathing animal merely got drunk.

From this and similar experiments Magnan insisted on a separate category for the small number of “absinthistes” in his asylum. Chronic absinthe users, he claimed, suffered from seizures, violent fits, and bouts of amnesia. He recommended a ban on the Green Devil.

Others found his claims unpersuasive. Responses in The Lancet, for one, noted flaws in his methodology, including the crucial differences between a guinea pig inhaling high doses of distilled wormwood and a human consuming trace amounts of diluted wormwood. More likely, many argued, excessive consumption produced the same alcoholism as with any other drink. The British were especially skeptical of his claims; not coincidentally, the United Kingdom was one of the few countries never to ban the drink, which had never gained popularity there.

When disease infected French vineyards in the 1880s, the resulting wine shortage helped popularize absinthe among the money-conscious working class.

But in France, Magnan’s theories fit into the larger cultural conversation. Defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 escalated already existing anxieties about France’s collective health and especially its ability to protect itself against a bellicose and populous neighbor. (After the war Germany had 41 million citizens compared with France’s 36 million.) Public-health concerns gained an existential force; those worried about the rise of absinthe dubbed it “the poisoning of the population.” Not only did it contribute to the ill health of the populace, these opponents argued, but it was also an abortifacient and sterilized men, robbing the country of a generation of potential soldiers.

Others had long reveled in the dark side of absinthe. Baudelaire, an unrepentant absintheur, had declared in 1861, “France is passing through a period of vulgarity.” He thoroughly enjoyed the onrushing modernity, with Paris madhouses filling up and an apparently inevitable decline of civilization. But by the 1890 publication of Magnan’s The Principal Clinical Signs of Absinthism, common opinion in France largely agreed with his conclusion: the absinthe did it.

Still, it took the Lanfray murders of 1905 to convert many citizens into activists. Previously the absinthe drinker symbolized moral decay, but he had never truly crystallized into a violent threat to society. Doctors disagreed about the danger, with Magnan and his disciples declaring absinthe the root of all social evil. On slim evidence some even linked it to tuberculosis. Meanwhile, other physicians continued to tout its health benefits, prescribing it for gout and dropsy, as a general stimulant of mind and body, as a fever reducer, and as the perfect drink for hot climates. Amid the medical uncertainty support for an outright ban remained a minority stance.

After the Lanfray murders absinthe consumption became a serious political issue, as people throughout Europe—reading lurid headlines about the “absinthe murder”—demanded action. Absinthe went on trial in the court of public opinion, facing a newly hostile citizenry, its longtime enemies in the temperance movements, and a bevy of respected medical authorities. Behind the scenes wealthy wine producers supported a ban in an attempt to eliminate an increasingly popular competitor, even though absinthe never accounted for more than 3% of the alcoholic beverages consumed in France. But when disease infected French vineyards in the 1880s, the resulting wine shortage helped popularize absinthe among the money-conscious working class. When the wine crisis ended, many working-class drinkers stuck with the green beverage, increasingly made with cheaper industrial alcohol produced from beets or grain. Yet wine still accounted for 72% of all alcohol consumed. More than actual competition, it was the appearance of a trend that provoked wine makers to move against absinthe. Meanwhile, Magnan’s distinction between alcoholism and absinthism allowed wine to escape any blame for the state of the national health.

In defense of the Green Fairy stood a collection of self-proclaimed decadents of the absinthe subculture (not always a politically active lot), and a few sympathetic politicians scattered throughout Europe. The outcome was never in doubt.

When Magnan died in 1916, he did so in a France freed from the shackles of the Green Devil. Absinthe faded into lore, kept alive through the stories of Parisian decadence. What remained were caricatures of mad geniuses who roamed from café to café calling out “une verte!” as they chased that next great insight, the transcendent perspective available only through the grace of the Green Fairy. Of course, anyone who knows this kind of story—romantic, poetic—knows the Green Fairy can never really die. Bootleggers in Switzerland continued to produce absinthe. Spain never outlawed the drink, and a few small distilleries produced it throughout the 20th century. In 1994 a Czech distiller began marketing absinthe in the United Kingdom, where, thanks to a legendary reputation, it became a hit among bohemian cognoscenti. Soon enough dozens of copycat brands appeared.

In response to pressure from their own distilleries—and perhaps noting the lack of modern “absinthe murders”—many European countries revised their absinthe bans. Most allowed only small amounts of thujone, the active ingredient in absinthe, in the new concoctions (see sidebar). But most aficionados knew that pre-ban absinthe always contained less than the now-mandated 10 mg/liter of thujone. The restrictions, later adopted by the European Union, effectively legalized absinthe. Switzerland lifted its ban on absinthe production and sale in March 2005. France, however, only allows the label “absinthe” on products destined for export. Absinthe produced for local consumption instead carries the label “spiritueux à base de plantes d’absinthe,” or “wormwood-based spirits.” The United States has complicated laws about “thujone-free” absinthe, making illegal the importation of most European varieties. Even in this diminished form it’s now legal to produce and sell absinthe in the United States. After nearly 100 years the Green Fairy lives again.

The Chemistry of Absinthe

Though a pioneer in French psychiatry, Valentin Magnan did not transcend the biases of his time. His diagnosis of “absinthism” lent the imprimatur of medical science to what might have otherwise remained a folk belief.

Bans helped solidify absinthe’s deadly reputation in popular culture, and subsequent scientific study was often overshadowed by Magnan’s work. With the relaxation of legal restrictions, scientists again began to examine the drink, homing in on its presumed active ingredient, thujone (C10H16O). Thujone, the essence of wormwood, was long thought to be hallucinogenic—based in part on literary descriptions from the likes of Baudelaire and Rimbaud. But little science existed to support this claim.

In 1975, noting similarities in the psychological effects attributed to absinthe with those of marijuana, researchers suggested comparing thujone with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the active ingredient in cannabis. Thujone and THC have similar molecular geometry: both have similar functional groups available for metabolism in humans; both are terpenoids; and though this large group contains Salvinornin A, the psychotropic molecule in Salvia divinorum, it also includes fewer controversial molecules, such as camphor and menthol.

Later research proved that thujone exhibits some affinity for cannabinoid receptors but does not stimulate the same responses as THC. Any intoxicating effects are not the same as those of marijuana’s active ingredient.

Thujone does, however, inhibit GABA-receptor activation; in extremely high doses this property can cause spasms and convulsions. At least one would-be absintheur required hospitalization after overdosing on wormwood oil. Researchers hypothesized that some pre-ban absinthes may have contained similarly high quantities of thujone, but chemical analyses revealed levels much lower than previous estimates.

Many now believe it unlikely that thujone—at least in the small amounts found in absinthe—can have a toxic effect. What then caused the “absinthism” observed by Magnan and his colleagues? Some suggest that without strong regulation and quality control, such adulterants as copper sulfate, antimony, or chloride could have poisoned absinthe drinkers. And inferior alcohol, used by distillers eager to turn a quick profit, could also have led to impaired vision, for example.

But the most likely culprit is perhaps also the most obvious: ethanol. The most prominent ingredient in absinthe after all is alcohol; maintaining wormwood in solution requires greater than 50% alcohol by volume. Stripped of its singular glamour and tabloid enchantments, “absinthism” looks like a much sadder and more common affliction: chronic alcoholism.