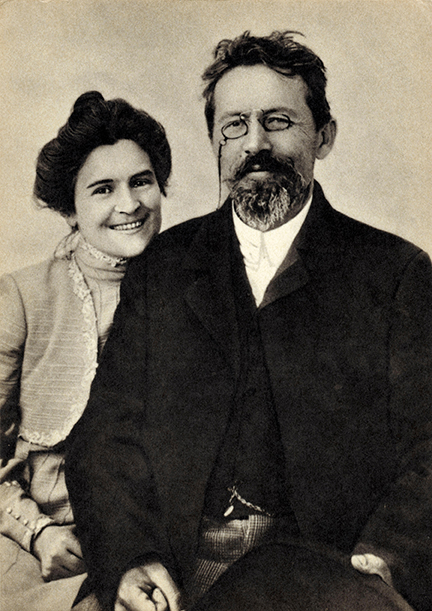

Despite the champagne the mood was somber. Anton Chekhov lay dying.

The playwright’s wife, actress Olga Knipper-Chekhova, later remembered, “He awoke in the early hours of the night, and for the first time in his life himself requested that the doctor be sent for.” When the German doctor arrived, “Anton sat up unusually straight and said loudly and clearly in German (of which he knew very little): Ich sterbe (‘I’m dying’).” The doctor ordered a bottle of champagne be brought up. “Anton took a full glass, examined it, smiled at me and said, ‘It’s a long time since I drank champagne.’ He drained it and lay quietly on his left side, and was soon silent forever.”

The stillness was interrupted by a huge black moth, “which kept crashing painfully into the light bulbs and darting about the room,” she wrote.

In the decades that followed, Chekhov’s death became, in the words of journalist and biographer Janet Malcolm, “one of the great set pieces in literary history.” Raymond Carver fictionalized it in his final short story, “Errand,” published in 1987. Carver doesn’t describe what happens to Chekhov’s body and possessions, but someone that day had the foresight to preserve the shirt he was wearing as well as the letters and postcards he had been writing during his stay. These materials would later tell the molecular story of his death.

Chekhov, the author of theatrical masterpieces including The Seagull, The Cherry Orchard, and The Three Sisters, had suffered from tuberculosis for two decades before his death in 1904. His biographers suspected he died, at age 44, of tuberculosis-related complications. But it would be 100 years and take the pioneering work of a team of 21st-century chemists to conclusively demonstrate what exactly killed the famed author.

This molecular analysis of Chekhov’s final moments, which began as a passion project among a few curious scientists, may dramatically change the way historians study valuable artifacts. That’s because the work is grounded in a poignant truth: everywhere we go we leave traces of ourselves. When we hold an object, cough or sneeze on it, we imbue that item with evidence of our illnesses, our habits, our meals. These imprints can outlive us. By combining sophisticated analytical chemistry with historical interpretation, scientists are beginning to illuminate not only what happened in the past but how it happened. And as a result historians accustomed to poring over rare manuscripts and aging artifacts may soon have new tools with which to study the intimate details of the daily lives, dietary habits, diseases, and manner of death of people long past.

Fingerprints from the Past

The smudge of a finger on a screen, like the one you’re using to read this story, is more than a blurring annoyance. It is a literal part of the person whose finger does the smudging. A fingerprint is composed of grease, grime, and trace amounts of proteins, primarily keratin—the scaffold for human skin.

Forensics experts have long used fingerprints to piece together the stories of crime scenes, though they scrutinize a fingerprint’s distinctive whorls, not the proteins themselves. But on a molecular level, human material can be even more telling.

Unlike DNA, proteins—such as the kind found in fingerprints—can be highly resistant to degradation, making them a more useful source of organic material on ancient artifacts. While DNA serves as an encyclopedia containing a vast breadth of information, protein records are more like newspapers, detailing the events of a given moment.

The oldest known protein is from a fragment of an ancient ostrich eggshell found in Tanzania, dating to 3.8 million years ago. (Paleontologist Mary Schweitzer has insisted she found proteins in a dinosaur specimen that’s 80 million years old, but this claim remains controversial.) More recently, archaeologists have begun to analyze proteins on ancient artifacts and even in dental calculus—preserved plaque—to study dietary habits of ancient peoples. In research published in fall 2018, Jessica Hendy of the University of York in England described proteins from potsherds dated to the Neolithic buried in Çatalhöyük, a village in Anatolia, Turkey. The potsherds yielded proteins from cattle, sheep, and goats, as well as from barley, wheat, and legumes. Hendy and colleagues were able to determine the barley proteins came from the endosperm, the edible part of the plant, suggesting the ceramic vessel once contained an ancient form of porridge or soup.

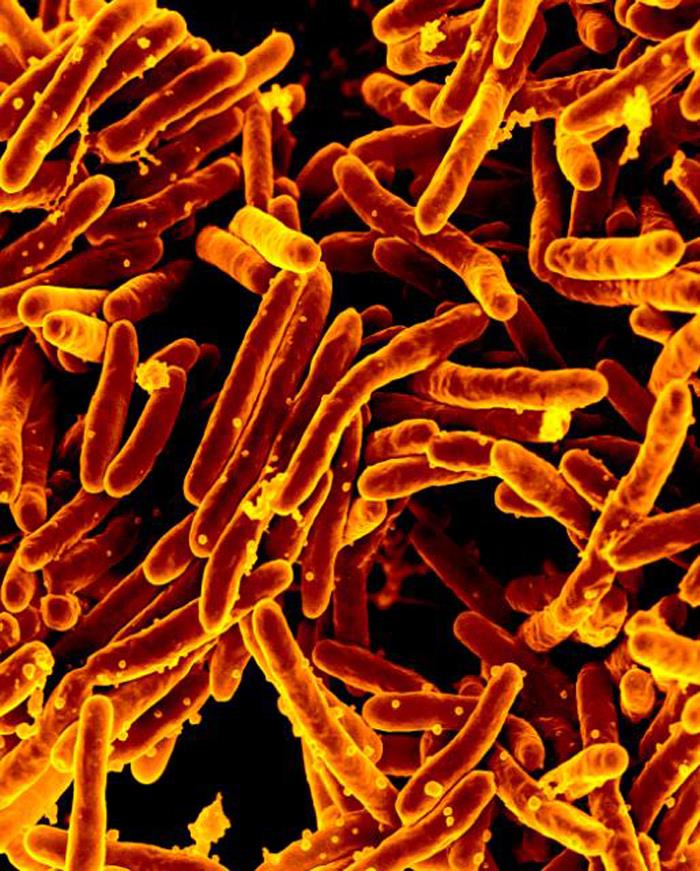

For Chekhov, the persistence of proteins would prove fateful. Mycobacterium tuberculosis spreads through airborne droplets that make their way into a person’s lungs. There the bacteria secrete proteins that allow them to invade cells and so begin to copy themselves, leading to a virulent infection.

Though writing made him famous, Chekhov was a physician, and he considered medicine his primary career. He attended medical school in Moscow in his early 20s and after graduating in 1884 began treating peasants and other poor Russians. That year he started coughing blood for the first time.

He must have known what his symptoms meant, but he concealed his illness from family and friends, even as his health worsened in the years that followed. “I am afraid to submit myself to be sounded by my colleagues,” he admitted to his close friend and publisher, Nikolai Leykin.

By 1887 the disease was taking its toll on the young doctor. Exhausted and sick, Chekhov took a short vacation to Ukraine. “There is a scent of the steppe and one hears the birds sing. I see my old friends the ravens flying over the steppe,” he wrote to his sister, Maria, that April. After returning home he wrote The Steppe, instantly famous for its vivid description of a storm.

Even as his fame and wealth grew—enough to buy an estate 40 miles south of Moscow near the village of Melikhovo—Chekhov’s health declined. In March 1897 he suffered a major lung hemorrhage while at a restaurant and was formally diagnosed with tuberculosis. Doctors ordered him to change his lifestyle and reduce his medical work. He sat down to write, completing two of his most famous plays, The Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard. Through his work in the theater he met the young Olga Knipper, eight years his junior. They married in secret on May 25, 1901, but their romance would prove short lived. By their third anniversary Chekhov was terminally ill. “Everyone who saw him secretly thought the end was not far off, but the nearer [he] was to the end, the less he seemed to realize it,” wrote his brother Mikhail.

On June 3, 1904, he and Olga traveled to a health spa in Badenweiler, Germany. He wrote optimistic letters to his family, assuring his sister and mother that his health was improving, all while he was wracked by bloody, hacking coughs. Inevitably, some of that blood and saliva spattered his clothing, bedsheets, and linens, leaving indelible traces of Chekhov himself. Though the playwright succumbed on July 15 of that year, his molecular traces would persist for generations, much like the story of his final sip of champagne.

Lifting the Fingerprints

Pier Giorgio Righetti is a semiretired chemist at the Polytechnic University of Milan whose work focuses on animal and food-related proteins. For two decades he has published research on proteomes. Just as a genome describes a complete set of genes, a proteome reflects the entire set of proteins that can be expressed in an organism. And in the same way that genomics describes the function, structure, and relationship of an organism’s DNA, proteomics is the study of all the proteins in a given cell, the interaction between them, and their form and structure.

In his spare time Righetti is an avid reader of novels, and he began reading the works of Chekhov and Mikhail Bulgakov, another Russian doctor and playwright, on the advice of some Russian graduate students. A few years ago, though, Righetti turned his sights away from the words on the page to the pages themselves. He wondered whether by analyzing the proteins left on manuscripts and diaries he could better understand the writers themselves.

Righetti first attempted this type of historical analysis in 2011, when he received an unusual request. Could he determine the composition of a Bible reportedly once owned by Italian explorer Marco Polo?

In 1271, at age 17, Polo traveled with his father, Niccolò, and uncle Maffeo to the court of Kublai Khan, in Shangdu, China. In their cargo Marco Polo carried a small Bible inscribed on ultrathin sheets of parchment. It apparently remained in China for the next four centuries, until falling into the hands of a Jesuit priest, who in 1685 brought it to Florence as a gift for the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo III. There it would remain, lost among the collections of the Laurentian Library, until it was found in 2010 in a state of decay. The museum’s curator gave a small piece of a ruined parchment page to Righetti, who set out to determine how it was made.

Marco Polo’s Bible contained vanishingly thin pages, roughly 80 microns thick. Given the diaphanous quality of the pages, biblical scholars had at one time thought the parchment was derived from the skin of lamb fetuses. Righetti and his colleagues aimed to demonstrate whether this was true and possibly shed light on how and when the parchment was made.

Righetti’s team, led by Lucia Toniolo, microwaved a fragment and dissolved it using an enzyme called trypsin. After purifying the sample they found eight proteins, each belonging to the genus Bos taurus, suggesting that the parchment—or at least that page—was produced from calf tissue, not from lamb fetuses as was believed. The calfskin suggested the parchment was probably made in southern France sometime before 1250. Between 1235 and 1300 scribes at the University of Paris, one of the major European universities, produced some 10,000 copies of the same livre de poche, or pocket Bible. Their quasi-industrial production supplied portable texts to theologians, itinerant priests, and monks. Righetti was thrilled that such ancient proteins could be connected to such a history.

All organisms on Earth make unique proteins for all of life’s processes. Many of these proteins are well studied, so the presence of a certain one can shed light on not only the animal or plant that made it but also what was happening to the organism at the time. “While DNA is generally the same from the time when an organism is born until it dies, proteins have different expression in different tissues, and proteins expressed in growth in younger individuals are different from proteins expressed in older individuals,” says Enrico Cappellini, who studies proteins in ancient artifacts and archaeological finds at the University of Copenhagen. Such variation in protein expression is how Toniolo knew the fragment taken from Marco Polo’s Bible came from a calf rather than a mature animal.

After studying Polo’s Bible, Righetti and his team worked to develop a nondestructive analysis technique that would do away with the need to microwave and disintegrate their target material. A 2015 report describes their work with the original manuscript of Mikhail Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita, a famous satire in which the devil visits the Soviet Union. Righetti says he had grown fond of the novel after a student recommended it, and he wondered if he could learn more about the author’s life and death.

The team studied the margins of Bulgakov’s pages, finding protein biomarkers associated with kidney disease. They also found traces of morphine, suggesting the painkiller helped Bulgakov finish his novel, which he completed just four weeks before his death in 1940 from an inherited kidney disorder. Rather than dissolving samples of the pages, Righetti used resin beads, placing them directly on the paper to extract the proteins. But after the team published an initial report on the technique, another scientist pointed out there was no certainty the beads hadn’t damaged the manuscript. Righetti agreed, and the team subsequently changed their process, immobilizing the beads inside a set of thin, plastic diskettes made of ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) film. The diskettes—originally designed for manuscript preservation—can lift acids and other material, including proteins, from paper.

Using the protein-gathering film, Righetti then went on to study the 1630 outbreak of bubonic plague that struck Milan, his home city. The Black Death swept through Lombardy that year, killing roughly half the population. Up to 2,000 people died every day during the plague’s peak from June through September.

“For a time all commerce was in coffins and shrouds, but even that ended,” noted one unnamed eyewitness, as quoted by British physician Robert Fletcher in 1898. “Though doors were open and coffers unwatched, there was no theft; all offenses ceased, and no cry but the universal woe of the pestilence was heard among men.”

Righetti says the plague still looms large in Milanese history, in part because such details were vividly brought to life in a beloved Italian novel, Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed. Righetti wanted to discover some of that history for himself.

His team studied the margins of death registries stored at Milan’s state archives, uncovering abundant evidence of the plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis, as well as rat droppings. What’s more, they found proteins from corn, rice, carrots, and chickpeas, providing a glimpse into the diet of the Milanese scribes. (They apparently did not take meal breaks, instead eating while methodically recording the death all around them.)

Researchers are constantly updating their techniques, says Righetti, learning better ways to lift material from the surface of a manuscript, shirt, shard of pottery, or piece of bone. He has focused on testing objects in which the manner of death is known, or at least suspected, as a form of control; as his detection methods improve, he aims to find clues that can answer mysteries so far unsolved by historians. In terms of what can be analyzed, the possibilities are virtually limitless.

“The idea that we are leaving traces behind is a very interesting one,” says Matthew Collins, a colleague of Hendy at the University of York who studies proteins in ancient artifacts. “I would struggle to imagine objects that would not contain proteins.”

Finding the Cause of Death

In April 2017 Righetti’s team was given permission to analyze the relics from Chekhov’s final days, both to test the researchers’ methods against the playwright’s known tuberculosis diagnosis and to better understand the hour of his death.

The researchers chose to analyze five letters and the shirt Chekhov wore as he died. It was good material to work with: M. tuberculosis proteins are particularly resistant to degradation, says Collins. The bacteria’s cell walls preserve the proteins inside, as do bloodstains.

The researchers moistened EVA diskettes, then gently placed them on brown-stained spots on the shirt and papers. The diskettes were left in place for 60 to 90 minutes so the EVA film could pick up and bind to proteins and other charged molecules. Then the researchers extracted and purified the collected proteins, analyzing them using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. The last step of analysis was by far the most time consuming, says team member Gleb Zilberstein, a scientist who pioneered the detection method at the Israeli sensor firm Spectrophon.

First, the unidentified protein molecules were vaporized and given an electric charge. A magnetic field then separated the particles into distinctive patterns—called a mass spectrum—based on their mass and charge.

“When we received the spectrum for 200 proteins, it was difficult to identify them,” says Zilberstein. Spectrophon technicians used a bioinformatic tool called Unipept to build a taxonomic tree that would enable them to match what they found to known protein patterns. Because Chekhov’s disease was known, Zilberstein first searched bacterial databases to find proteins characteristic of M. tuberculosis. He also looked through general protein databases to match other possible organisms to the proteins from Chekhov’s shirt and letters. Ultimately, the researchers wanted to find proteins as well as their by-products, which could shed light not just on the disease but on its specific processes and even on the medications administered.

After a year of work the team isolated 108 proteins found in human blood. The group also found definitive evidence for M. tuberculosis, which surprised no one. What makes the discovery significant is the tiny volume of material used to make it, Zilberstein says; the droplets of blood represented a minuscule sample size.

“Our team was lucky, because fortunately we found traces of spittle and saliva and traces of blood, so we were able to identify the traces of tuberculosis,” says Zilberstein.

And the team found something else.

Among the protein markers in the sample they found a protein known as ITIH4, which is produced in response to blood clots. This suggests that the immediate cause of Chekhov’s death was not heart failure or suffocation caused by the infection itself but a stroke, which cut off blood supply to an artery in the writer’s brain.

Zilberstein says the team is still conducting bioinformatic analysis to figure out what other diseases Chekhov may have had that could have led to the production of ITIH4. But he and Righetti say the manner of Chekhov’s death is now well understood. Chemical truths illuminate the gothic literary scene: as a hapless black moth fluttered and thumped against a lamp, a massive blood clot extinguished the playwright’s own light.

Unsolved Mysteries

Zilberstein and Righetti are optimistic that their methods will become a favored technique for studying valuable artifacts and will allow us to tell more detailed stories about people in the past. Beyond simply confirming or discovering the name of a disease, historians can bring to light the drugs used to fight it and to ease the patient’s pain.

Proteomics research on historical rarities is in its infancy. The earliest paper in the field dates to 2000, and there are still no widely accepted standards for collection and analysis. Modern mass spectrometry methods are sensitive enough to detect tiny traces of material. But materials that are decades, centuries, or millennia old are fragile, and methods to detect and study proteins can damage the proteins and the artifacts themselves. Hendy recently published a manifesto calling for proteomics researchers to adopt new standards for handling and analyzing material, both to safeguard historically valuable materials and to ensure reproducible science.

For his part Collins uses electrostatic retrieval to collect proteins, harnessing the same force that causes a latex balloon to cling to a person’s hair. The method may be safer for testing certain documents, such as parchment, but it is less effective than Zilberstein’s water-dampened diskettes.

The true test of proteomics research will be its ability to answer unsolved mysteries. In the cases of Chekhov, Bulgakov, and the victims of the plague, the causes of death—or at least the presence of a specific disease—were already known. But unmasking a previously unknown killer would be even more valuable.

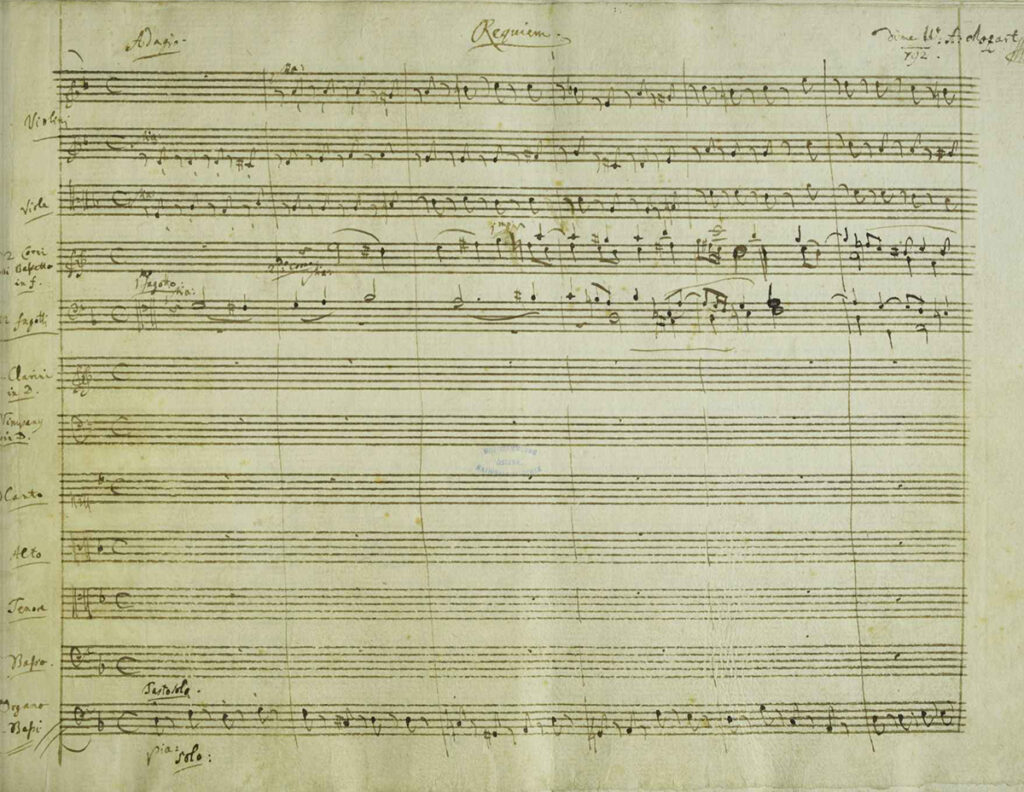

Righetti, for instance, would like to study the final pages of Mozart’s Requiem, which the composer was still finishing at the time of his death at age 35. “We hope to find out how he died, which is at present still mysterious. But the curator of these pages at the Vienna museum [gave us] a stern refusal, for unknown reasons,” Righetti said.

Zilberstein has also faced pushback. He has been stymied in his attempts to study the bloody clothing worn by Russian writer Alexander Pushkin, who was killed in a duel with his brother-in-law. Zilberstein, who himself is Russian, hopes to find out more about Pushkin’s African ancestry. (The poet’s great-grandfather, Ibrahim Petrovitch Gannibal, was African; kidnapped as a child, he was raised as a godson of Peter the Great.) So far the Pushkin museum has denied Zilberstein’s request.

Postscript

Historians can learn much from a manuscript, a garment, or any other relic by relying on historical knowledge and context. But there are also depths to be mined in the more quotidian details of a life lived, a sickness suffered, even a meal shared.

“The protein component in historical material is extremely rich and constantly present,” Cappellini says. “The kind of information we can obtain from this material is . . . precious. As a consequence we experience the history of the object.”

Chekhov could not have known that the traces of his death would continue to tell his story, but he might have appreciated this knowledge and the notion that a part of him would persist far into the future. Before being killed in a duel Baron Tuzenbach, a character in The Three Sisters, muses on the meaning of death:

“What trifling things, what idiotic little details sometimes acquire quite suddenly a significance in one’s life, for no reason whatsoever,” Tuzenbach says. “Look, there’s a tree which has withered, but it still sways in the wind like the other trees. So, I think, if I should die, I shall still be a part of life, like that, or in some other way.”