Sometime around 1980 in Bonners Ferry, Idaho, Phil Allegretti came across an old can of bug killer in the attic of a theater. Something about the can’s retro look struck Allegretti, so he picked it up and carried it home. He didn’t know it at the time, but it would be the first can of many.

“Every time I’d be in an old house or under a house or in an old barn or whatever, we would always find old pesticide cans,” says Allegretti, a now semiretired exterminator and weed-control specialist. “I would pick them up wherever I could. I’d see them in yard sales and farm sales and all that type of thing.”

To his growing collection of cans Allegretti began adding the sprayers and diffusers used to spread the chemicals. The hobby raised some eyebrows among family members, but he carried on, becoming more selective while combing flea markets and Ebay. Online he’d meet other collectors.

“I remember one guy I met, he called them death tins. . . . He had an incredible collection of the older cans,” Allegretti says. “I guess if there’s something out there, there’s somebody going to collect it, right?”

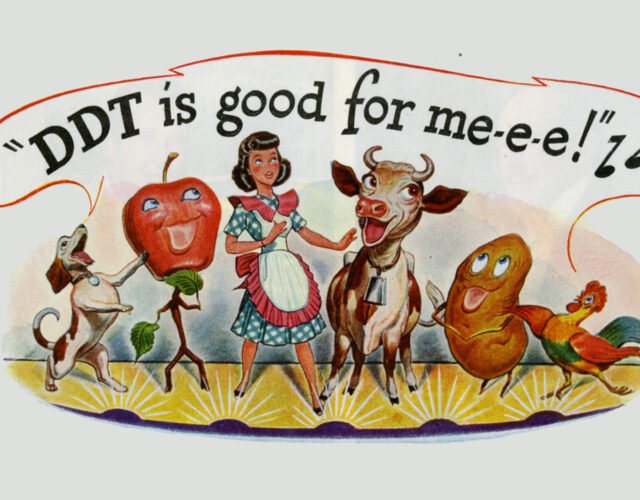

Many of the containers and sprayers Allegretti amassed are playfully decorated and named. Cartoony insects teem around the edges of brightly colored bottles of Fly Ded, which kills its enemies with “the new miracle pesticide” DDT.

A sprayer-toting soldier stands guard on cans of Flit. Introduced by Standard Oil in 1923, the original Flit used mineral oil to exterminate flies and mosquitoes; DDT was added to the mix in the late 1940s. By that point Flit had become wildly popular thanks in large part to a line of cartoon advertisements created by Theodor (Dr.) Seuss Geisel.

But the playfulness of such marketing was often offset with fear mongering.

“Do roaches spread cancer?” asks an advertisement for Tanglefoot spray. An ad for Trimz DDT-coated wallpaper is more direct: “Protect your children from disease-carrying insects!” The wallpaper features Bambi and other well-known Disney characters and promises to protect baby and home from a single flea’s “6,600,000 bacteria.”

Allegretti has never been able to track down the Disney-themed wallpaper, but he did find a roll of cedar-patterned Trimz. “Better than a genuine cedar closet,” the package insists, “because it kills insects.”

Such laissez-faire marketing of DDT can startle 21st-century eyes.

“It was just surprising to me being that I was trained and had to have licenses [to be an exterminator],” Allegretti says. “I’ve got 14 categories on my license in Idaho, all these different categories of pesticides. It amazed me that they just sold DDT over the counter.”

As his collection took shape, Allegretti wanted the world to see it. He considered taking pieces to local libraries or professional conferences, but carting the stuff around never seemed feasible. He thought some place out there might be interested in giving it a permanent home, but where?

One night Allegretti was watching the Travel Channel’s Mysteries at the Museum. As luck would have it, the episode featured CHF in a story about William H. Perkin and his discovery of mauve. Allegretti reached out to Kristen Frederick-Frost, CHF’s curator of artifacts at the time.

“I remember reading ‘DDT’ in the e-mail subject line and thinking ‘no way,’” says Frederick-Frost. “After I looked at the collection photos, I did a complete 180. It is an incredibly evocative collection. We couldn’t ask for a better way to illustrate our love-hate relationship with pesticides.”

The collection reveals just how pervasive DDT was in American life in the mid-20th century. And oddly, it hints at an era’s obsession with multifunctionality. Vacuum cleaner attachments, such as the Whirl-A-Way Insector, gassed moths and larvae as the machine swept the carpet. And with the Arnold garden-hose sprayer you could battle pests with DDT or lead arsenate (cheerfully marketed as Arsen-O-Spray) while watering the tomatoes.

Assessing the legacy of DDT and other organochloride pesticides is complicated. These chemicals threatened human and animal health—most famously exposed in Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring—but also helped save hundreds of thousands of human lives in areas beset by malaria and other insect-borne diseases. Allegretti embraces this ambiguity.

“It kind of spiraled out of control the way I look at it,” he says. “I mean, it was a great chemical, but, geez, they sprayed it on everything, if you look at those cans.”

Allegretti hopes the collection will stir a dialogue about the chemicals that have become commonplace in our lives. His collection has already sparked a (frankly uncivil) exchange in the comments section of Wired’s website, which ran a story on the collection this summer. The dialogue is a typical battle of opinion, fact, and name calling.

“The biggest kick I got out of that whole [Wired] article was the people just angrily trying to talk each other down about DDT,” Allegretti says. “So you have two sides that have always talked about DDT: pro-DDT and anti-DDT, and it still goes on.”