The landlady opened the closet and nearly vomited at the smell. What had those two students left inside this bundle of clothing?

When they rented the room two weeks before, they’d seemed like decent enough fellows and had even paid upfront. But after hauling the clothes up the stairs, they’d disappeared and left her to clean up the mess.

Holding her nose, she picked up the pile—at which point two arms and legs tumbled out. The landlady had just uncovered one of the most notorious murders of 19th-century Paris, a case that would prove sensational not only for the grisly crime, but for who would take the blame—none other than Charles Darwin.

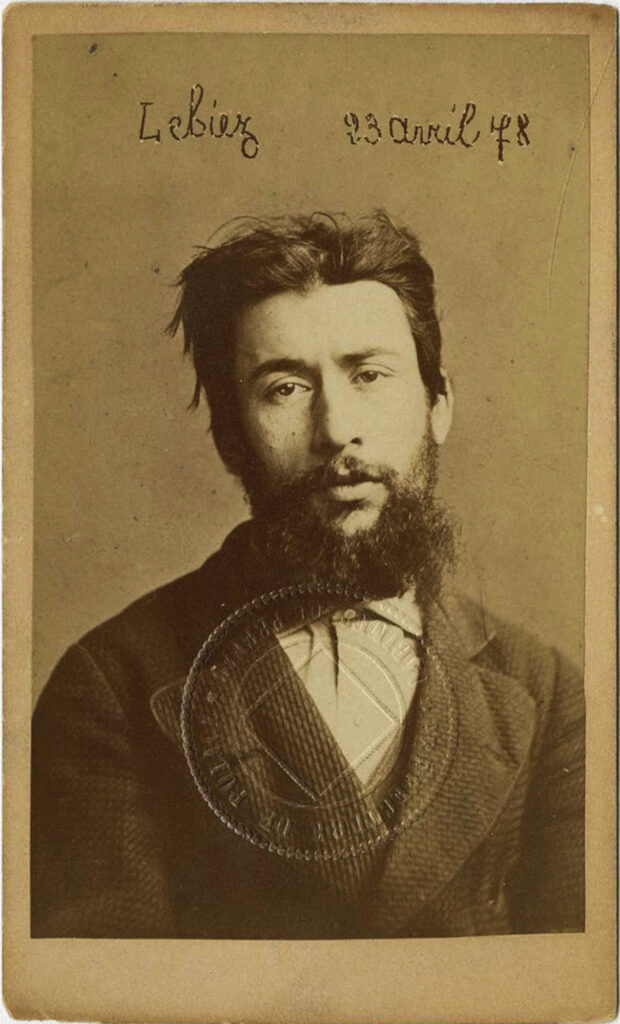

Paul Lebiez was the tall, handsome, 24-year-old son of a photographer. In high school, in the early 1870s, he distinguished himself as a sharp science student, especially in anatomy. He later applied to join the navy as a doctor, but the navy rejected him for bad character; although many friends described him as warm and happy-go-lucky, others called him “difficult and unruly.” He also had a reputation as a political firebrand.

Lebiez began teaching elementary school in Paris instead but was fired for chronic tardiness. He soon ran up several debts and took to underhanded methods of raising cash, pawning his lover’s wig and stealing books from his friends’ shelves to sell. Then, in 1878, he heard a tale of woe from an old school friend and devised a more devious scheme.

That friend was Aimé Barré, a bearded, 25-year-old stockbroker whose tastes outran his budget. Barré’s stock-market speculations rarely paid off, and he was drowning in even more debt than Lebiez. That didn’t stop Barré from moving into an expensive new apartment near Notre Dame.

In this neighborhood, Barré noticed an old milk seller named Gillet. She had gnarled hands and a scarred left arm. She was also thrifty. Local gossips swore she had 5,000 francs squirreled away (roughly $15,000 today)—enough to leave Barré drooling. He begged Gillet for permission to run her estate, promising to double her wealth. Gillet refused, and Barré groused to Lebiez about this missed opportunity.

Although old friends, Lebiez differed from Barré in one, key way. Barré was grubby, materialistic. Lebiez had an intellectual streak. One of his touchstones was Charles Darwin’s new theory of evolution by natural selection.

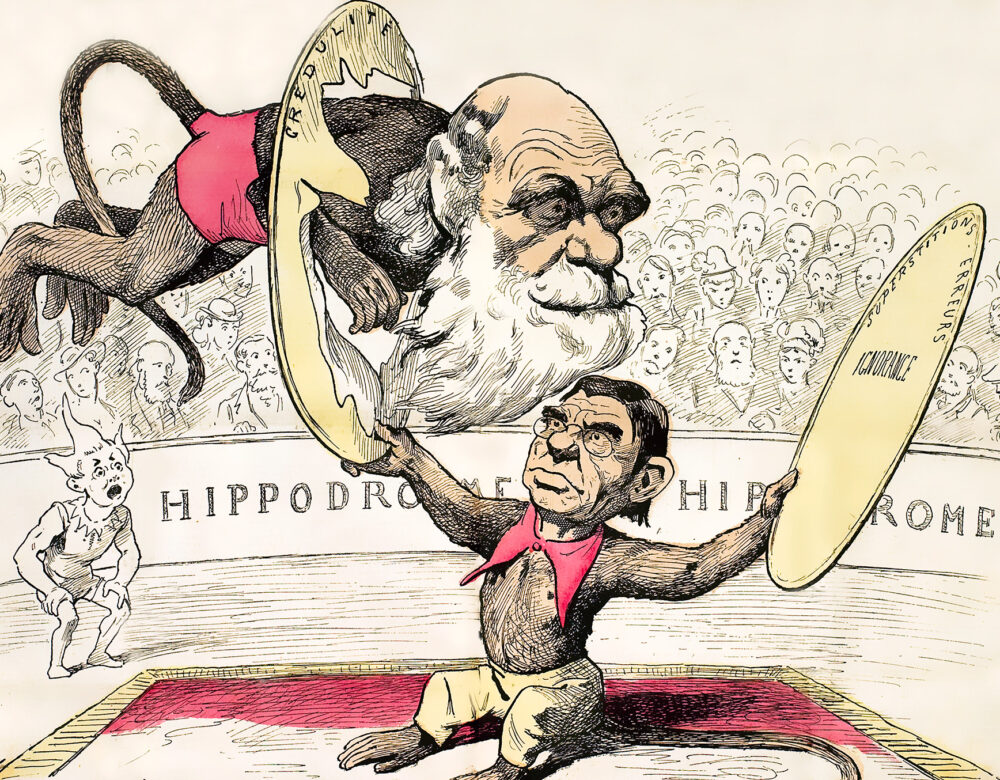

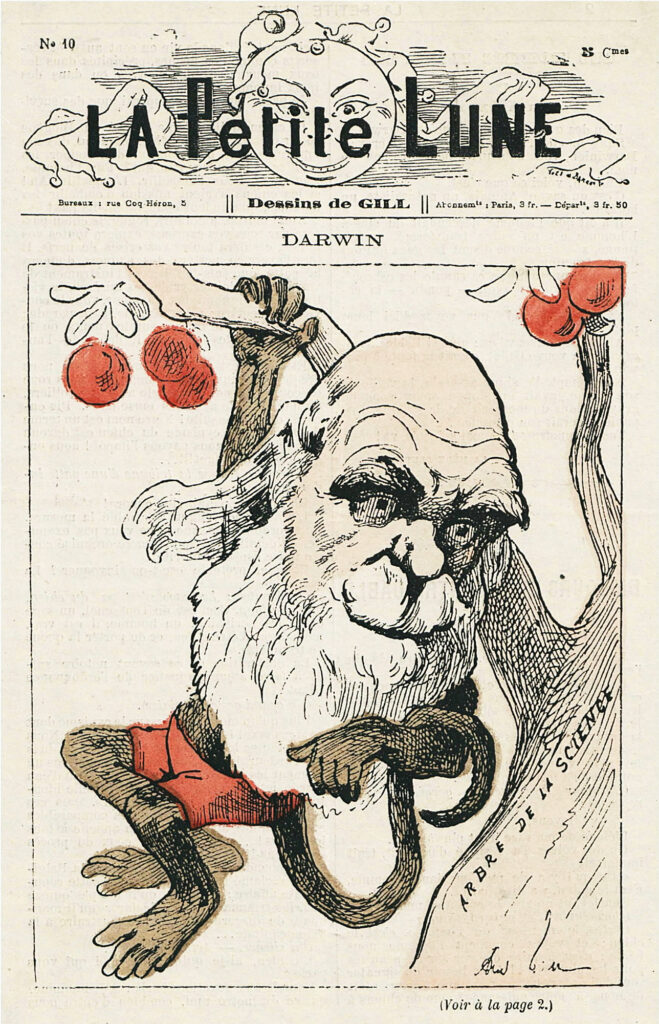

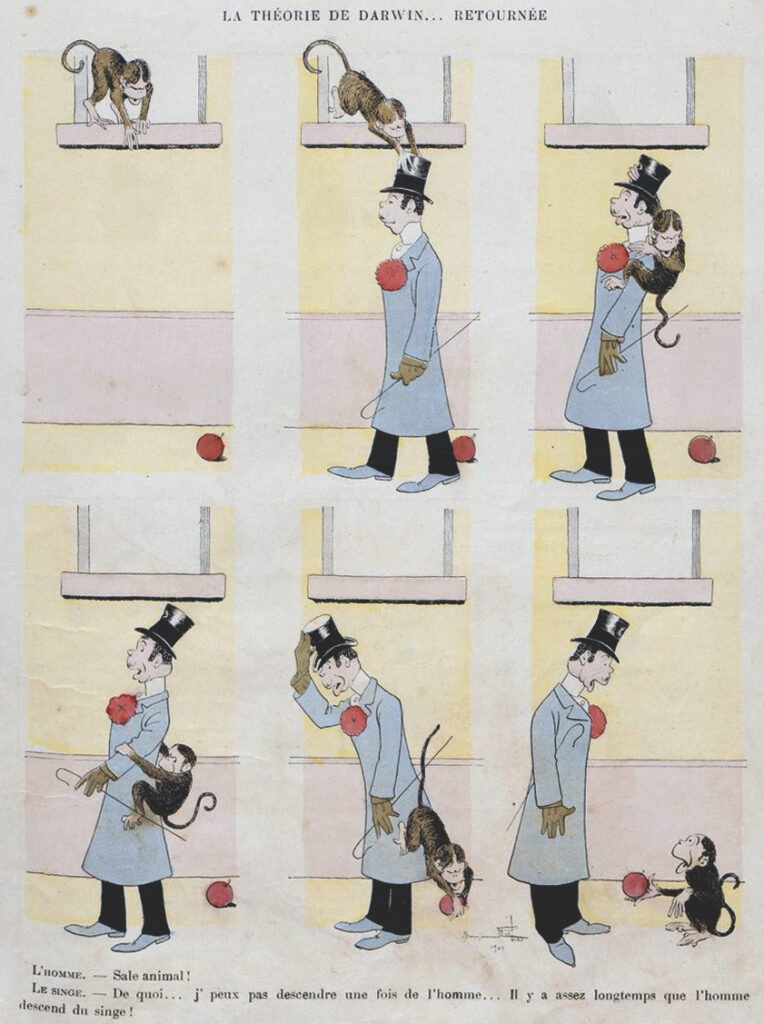

Darwin has always been controversial, but he was especially so in France. Part of this was good old-fashioned snobbery—the reflexive French disdain for anything English. Catholics and conservatives in France also fretted that evolution seemed to displace God and undermine traditional morals. At the time, France was still reeling from the political upheaval that culminated in the Paris Commune in 1871 and the bloody crackdown that quashed the republican uprising. Conservatives were positioning themselves as the upholders of order and stability—a stability that Darwin’s ideas were threatening to undermine. Darwin therefore needed stamping out.

Even French scientists were split over Darwin. Some of them insisted on the immutability of species. Other scientists held a torch for the evolutionary theories of their countryman Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who promoted a looser, use-it-or-lose-it theory of evolution. Still others saw Darwin’s merit but hesitated to support him publicly for fear of being labeled an atheist or radical. Darwin’s support was especially weak among the establishment types who dominated the august French Academy of Sciences. Six separate times progressive scientists had nominated Darwin for election to the academy—and six separate times, he had been voted down. The message was clear: Darwin had no home in France.

Paul Lebiez, however, adored Darwin and wasn’t shy about it. So when Barré mentioned the milkmaid who had spurned his offers to manipulate her finances, Lebiez broke the situation down along Darwinian lines—or at least his interpretation of Darwin. “What right has she to hoard up her gold when there are many others who could put it to some use?” he ranted. According to Lebiez’s thinking, weak people like Gillet had a duty to give way to strong people like him. This was simply Darwinism in action.

Lebiez certainly wasn’t the first person to twist Darwin’s ideas in this way. A decade earlier, Englishman Herbert Spencer began promoting so-called social Darwinism, which conceived of human life in terms of strong people brushing aside the unfit, and powerful nations dominating weak ones. In Spencer’s worldview, there was no room for pity or remorse.

Paul Lebiez in Paris adopted Spencer’s ideas as his ethical principles. And those principles led him to make a chilling suggestion to Barré: to kill the milkmaid Gillet and make off with her money. Barré agreed.

Because Barré had met Gillet before, he took it upon himself to weasel his way into her apartment and dispatch her there. He talked his way in on three separate occasions, but each time he chickened out. A chagrined Barré finally agreed to lure Gillet to his apartment instead, so Lebiez could help.

On March 23, 1878, Barré asked Gillet to deliver some milk. She arrived around 10 a.m. Barré let her in with a smile—then smashed her skull with a hammer. After crumpling to the floor, Gillet cried out for mercy. But a lurking Lebiez ran up and stabbed her six times in the heart with a stiletto-shaped ink eraser.

The squeamish Barré left the scene to ransack Gillet’s apartment. Meanwhile, Lebiez used his anatomical training to dismember Gillet’s body. He packed her head and torso into a trunk and wrapped her arms and legs in some blue blouses Barré had bought for his mistress.

Barré returned from Gillet’s apartment with bad news. Neighborhood scuttlebutt had exaggerated the milkmaid’s wealth. Rather than 5,000 francs, Gillet had only 2,000 to her name (roughly $6,000 today).

Barré then made a proposal—that he, who had bigger debts, should keep the lion’s share of the loot. Sources differ on the exact amount, but at most he offered Lebiez 75 francs. Incredibly, the cold-blooded Lebiez agreed and walked away with the modern equivalent of less than $250. Apparently, carrying out his Darwinian duty was reward enough.

The coverup was as clumsy as the murder. Lebiez and Barré shoved the trunk with the torso and head onto a train bound for Le Mans. Then they rented a room from the landlady under false names and dumped the bundled limbs in the cupboard.

After discovering the arms and legs, the landlady alerted the police, who began inquiring about missing people around town. On April 17 they received a report about the disappearance of Gillet, who witnesses said had a scar on her left arm that matched the scarred left arm found in the room.

From there, things proceeded swiftly. Neighbors told police that Barré had been hounding Gillet for money. On April 19, Good Friday, the police hauled Barré into the station, where the landlady identified him. Barré confessed and implicated Lebiez, who was arrested on Easter Sunday while vacationing in the countryside.

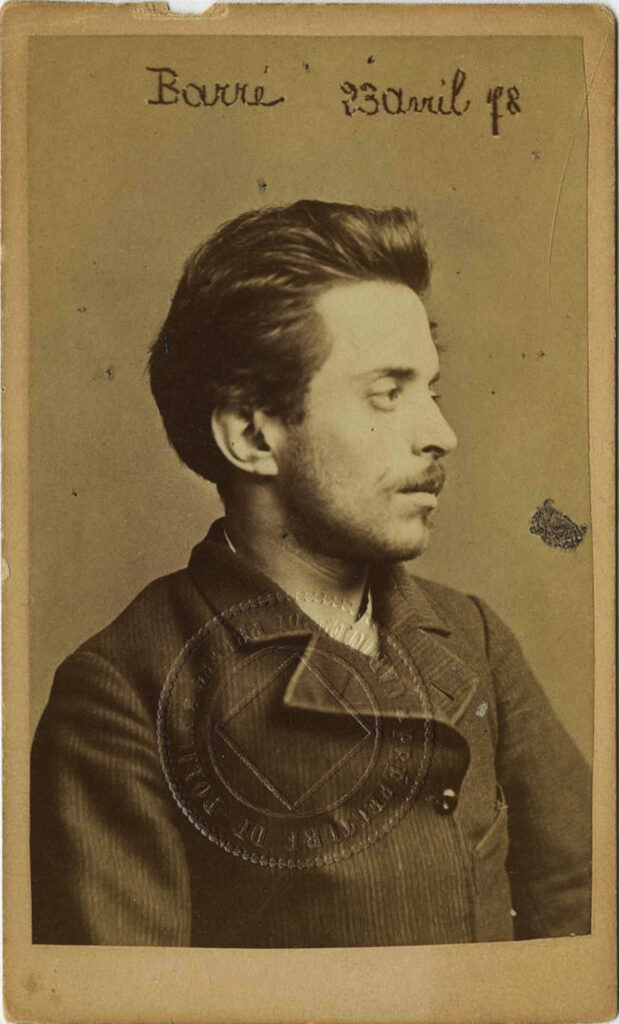

Mugshots of Paul Lebiez (left) and Aimé Barré after their arrest.

Archives de la Préfecture de police de Paris

The French tabloids ran screaming headlines about the murder. But however sordid, the tale probably would have faded from history if not for one detail. During their investigation, the police learned that on April 11, less than three weeks after the murder, Lebiez had given a public lecture on Darwinism and the “natural” tendency for the strong to dominate the weak. “At the banquet of Nature there is not room, there are not covers laid for all the guests; each one struggles to find a place; the strong push out the weak,” he told his audience. “Hence this struggle for life, family against family, species against species, a civil war without peace or truce.”

It didn’t exactly take Sherlock Holmes to link these sentiments to the motive for Gillet’s murder. And many in the French establishment saw those words as a golden opportunity. Catholics, conservatives, and their allied newspapers began denouncing Lebiez as a heinous criminal and using him as a cudgel to destroy Darwin and his theories of evolution.

Those newspapers claimed that, far from perverting Darwinism, Lebiez had simply followed it to its logical conclusions. One called him a “puppet intoxicated by the doctrine of his master.” In this view, Darwinism was nothing more than amoral, might-makes-right nihilism. Society therefore had a duty to root out this evil.

It’s easy to imagine people reading and nodding along. But as the campaign to destroy Darwin picked up momentum, something funny happened, historian Liv Grjebine recently discovered.

Given the murder and the denunciation campaign, even moderate and progressive newspapers felt compelled to run stories about Lebiez and Barré’s crime. In doing so, they described Darwin’s theories on evolution. Unlike conservative papers, most took pains to explain natural selection fairly, minus distortions and smears. And oddly enough, when everyday people began reading what Darwin actually said, a lot of them decided it made sense—especially when respected scientists began weighing in. The murder and public controversy surrounding it forced reluctant scientists to take public stands in support of Darwin in meetings and interviews. Thus arose a virtuous cycle. The more that common people read about scientists supporting Darwin, the more public opinion shifted in his favor. This made it easier for other scientists to pipe up, which shifted public opinion further. Which encouraged still more scientists to speak out, and so on. Gradually, the great tide of public opinion began to lift Darwin out of the muck despite the negative publicity from the murder trial.

After months of headlines, the trial of Barré and Lebiez opened in late July 1878 and lasted just a few days. Cravenly, each man blamed the whole mess on the other. The jury believed neither and swiftly returned a sentence of death by guillotine. The two were executed in early September.

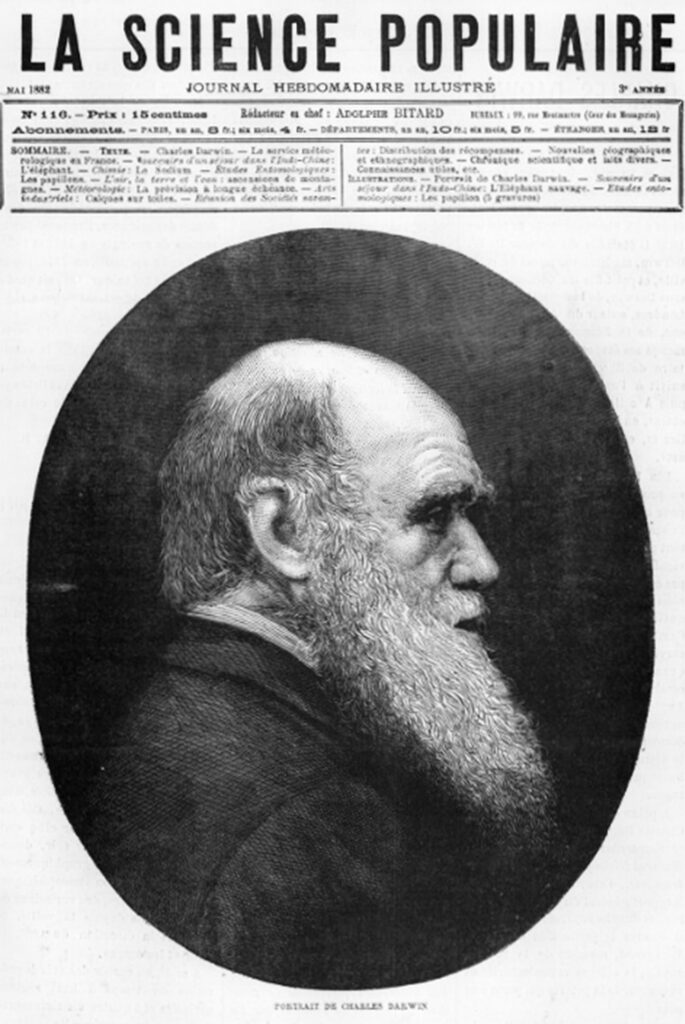

Just four days after the trial ended, the French Academy of Sciences once again took up the question of whether to elect Charles Darwin a member. Despite the murder trial and accusations from the Catholic Church, the academy finally accepted Darwin. The results weren’t a landslide, and the scientists who voted aye justified themselves by muttering about Darwin’s contributions to botany. But the timing spoke volumes. And while the conservative press tried to rally—claiming that the academy had endorsed Darwin the scientist, not Darwin-ism, or that whatever the truth of Darwin’s theories, he was still corrupting the minds of the youth—the public interpreted the election as a slap to those who had disparaged the great naturalist.

Attacks on Darwin certainly didn’t stop after Barré and Lebiez’s trial. The very next year, a newspaper reported another murder under the headline “Darwin the Assassin.” But Gillet’s death proved a tipping point, however grisly and inadvertent, in French society’s long and fitful acceptance of Charles Darwin and his controversial theory of evolution.