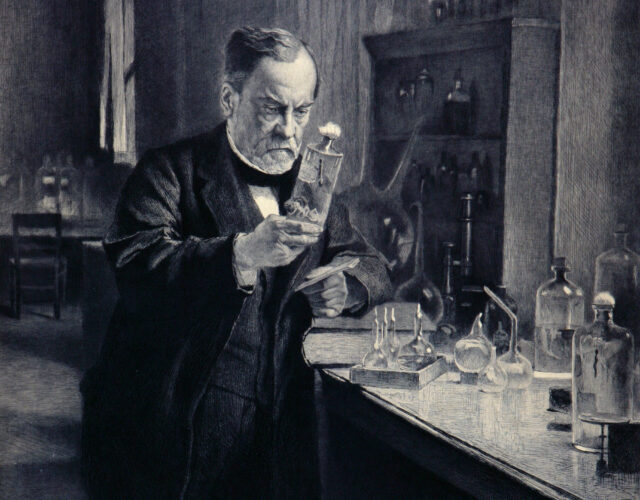

Louis Pasteur holds a drying bottle, contemplating a piece of nerve tissue from a rabid rabbit. He’s using the bottle to attenuate the deadly hydrophobia virus, the key to his lifesaving rabies shots. In this brilliant portrait there is no sign of friendship, but it was fundamental to the painting’s creation. In fact, the history of this print reveals two friendships.

Pasteur began his career in physical chemistry but went on to revolutionize biology and medicine. By age 63 he had made discoveries in stereochemistry, fermentation, the preservation of wine, and diseases of silkworms. He had abolished the notion that simple creatures can be generated spontaneously from organic compounds without any parent organisms. He had established evidence for the germ theory of disease and produced a vaccine for anthrax.

In spring 1885 Pasteur invited a young Finnish artist, Albert Edelfelt, to paint a large formal portrait. They had become close friends a few years earlier through Pasteur’s son, Jean-Baptiste, a part-time journalist who often wrote about art.

Edelfelt was responsible for the unprecedented scene in the painting. Portraits of eminent people made at this time rarely included a naturalistic setting and almost never a realistic workplace. The artist recorded his ambitions in a letter home. “Monday, I will again go to see the old fellow Pasteur to see if there is a possibility to make something of him in the laboratory because it is only there, in that environment, that I want to paint him. The old fellow Pasteur in tails and high collar is something ridiculous. No—he has to be in his own element.”

Not only did Pasteur consent to the painter’s presence in the crowded laboratory over several weeks, but he also worked with Edelfelt on the composition. “He has gone through all the accoutrements I placed around him, asking me to take away some of them, ‘the objects that are useless from the scientific point of view,’ and to replace them with other objects.”

The portrait’s huge success at the Paris Salon in the spring of 1886 created a market for prints. Lithographs, etchings, and engravings were used since photographs could not yet capture the tonal range of a canvas over five feet high. Such a handmade reduction required special skill, and Edelfelt was thrilled when he learned that a dealer had commissioned Léopold Flameng to make an etching, pronouncing him “France’s best.” The subtleties of the large painting are preserved exceptionally well even in this modestly sized print (21¼ × 17½ inches).

The copy in CHF’s collection—an original artist’s proof—reveals a second friendship. Printmakers do their own imprints to check the state of the finished metal plate. Flameng liked this particular impression so well that he kept it and personally inscribed it later “to my dear friend,” for Paul Raymond-Signouret, a writer known for art-exhibition catalogues and French translations of plays, including Shakespeare’s Macbeth.